The Action Turn: Toward a Transformational Social Science

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 'Van Dyke' Mango

7. MofTet, M. L. 1973. Bacterial spot of stone fruit in Queensland. 12. Sherman, W. B., C. E. Yonce, W. R. Okie, and T. G. Beckman. Australian J. Biol. Sci. 26:171-179. 1989. Paradoxes surrounding our understanding of plum leaf scald. 8. Sherman, W. B. and P. M. Lyrene. 1985. Progress in low-chill plum Fruit Var. J. 43:147-151. breeding. Proc. Fla. State Hort. Soc. 98:164-165. 13. Topp, B. L. and W. B. Sherman. 1989. Location influences on fruit 9. Sherman, W. B. and J. Rodriquez-Alcazar. 1987. Breeding of low- traits of low-chill peaches in Australia. Proc. Fla. State Hort. Soc. chill peach and nectarine for mild winters. HortScience 22:1233- 102:195-199. 1236. 14. Topp, B. L. and W. B. Sherman. 1989. The relationship between 10. Sherman, W. B. and R. H. Sharpe. 1970. Breeding plums in Florida. temperature and bloom-to-ripening period in low-chill peach. Fruit Fruit Var. Hort. Dig. 24:3-4. Var.J. 43:155-158. 11. Sherman, W. B. and B. L. Topp. 1990. Peaches do it with chill units. Fruit South 10(3): 15-16. Proc. Fla. State Hort. Soc. 103:298-299. 1990. THE 'VAN DYKE' MANGO Carl W. Campbell History University of Florida, I FAS Tropical Research and Education Center The earliest records we were able to find on the 'Van Homestead, FL 33031 Dyke' mango were in the files of the Variety Committee of the Florida Mango Forum. They contain the original de scription form, quality evaluations dated June and July, Craig A. -

Leadership and Ethical Development: Balancing Light and Shadow

LEADERSHIP AND ETHICAL DEVELOPMENT: BALANCING LIGHT AND SHADOW Benyamin M. Lichtenstein, Beverly A. Smith, and William R. Torbert A&stract: What makes a leader ethical? This paper critically examines the answer given by developmental theory, which argues that individuals can develop throu^ cumulative stages of ethical orientation and behavior (e.g. Hobbesian, Kantian, Rawlsian), such that leaders at later develop- mental stages (of whom there are empirically very few today) are more ethical. By contrast to a simple progressive model of ethical develop- ment, this paper shows that each developmental stage has both positive (light) and negative (shadow) aspects, which affect the ethical behaviors of leaders at that stage It also explores an unexpected result: later stage leaders can have more significantly negative effects than earlier stage leadership. Introduction hat makes a leader ethical? One answer to this question can be found in Wconstructive-developmental theory, which argues that individuals de- velop through cumulative stages that can be distinguished in terms of their epistemological assumptions, in terms of the behavior associated with each "worldview," and in terms of the ethical orientation of a person at that stage (Alexander et.al., 1990; Kegan, 1982; Kohlberg, 1981; Souvaine, Lahey & Kegan, 1990). Developmental theory has been successfully applied to organiza- tional settings and has illuminated the evolution of managers (Fisher, Merron & Torbert, 1987), leaders (Torbert 1989, 1994b; Fisher & Torbert, 1992), and or- ganizations (Greiner, 1972; Quinn & Cameron, 1983; Torbert, 1987a). Further, Torbert (1991) has shown that successive stages of personal development have an ethical logic that closely parallels the socio-historical development of ethical philosophies during the modern era; that is, each sequential ethical theory from Hobbes to Rousseau to Kant to Rawls explicitly outlines a coherent worldview held implicitly by persons at successively later developmental stages. -

Road Map for Developing & Strengthening The

KENYA ROAD MAP FOR DEVELOPING & STRENGTHENING THE PROCESSED MANGO SECTOR DECEMBER 2014 TRADE IMPACT FOR GOOD The designations employed and the presentation of material in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the International Trade Centre concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. This document has not formally been edited by the International Trade Centre. ROAD MAP FOR DEVELOPING & STRENGTHENING THE KENYAN PROCESSED MANGO SECTOR Prepared for International Trade Centre Geneva, december 2014 ii This value chain roadmap was developed on the basis of technical assistance of the International Trade Centre ( ITC ). Views expressed herein are those of consultants and do not necessarily coincide with those of ITC, UN or WTO. Mention of firms, products and product brands does not imply the endorsement of ITC. This document has not been formally edited my ITC. The International Trade Centre ( ITC ) is the joint agency of the World Trade Organisation and the United Nations. Digital images on cover : © shutterstock Street address : ITC, 54-56, rue de Montbrillant, 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Postal address : ITC Palais des Nations 1211 Geneva, Switzerland Telephone : + 41- 22 730 0111 Postal address : ITC, Palais des Nations, 1211 Geneva, Switzerland Email : [email protected] Internet : http :// www.intracen.org iii ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS Unless otherwise specified, all references to dollars ( $ ) are to United States dollars, and all references to tons are to metric tons. The following abbreviations are used : AIJN European Fruit Juice Association BRC British Retail Consortium CPB Community Business Plan DC Developing countries EFTA European Free Trade Association EPC Export Promotion Council EU European Union FPEAK Fresh Produce Exporters Association of Kenya FT Fairtrade G.A.P. -

To Clarify These Terms, Our Discussion Begins with Hydraulic Conductivity Of

Caribbean Area PO BOX 364868 San Juan, PR 00936-4868 787-766-5206 Technology Transfer Technical Note No. 2 Tropical Crops & Forages Nutrient Uptake Purpose The purpose of this technical note is to provide guidance in nutrient uptake values by tropical crops in order to make fertilization recommendations and nutrient management. Discussion Most growing plants absorb nutrients from the soil. Nutrients are eventually distributed through the plant tissues. Nutrients extracted by plants refer to the total amount of a specific nutrient uptake and is the total amount of a particular nutrient needed by a crop to complete its life cycle. It is important to clarify that the nutrient extraction value may include the amount exported out of the field in commercial products such as; fruits, leaves or tubers or any other part of the plant. Nutrient extraction varies with the growth stage, and nutrient concentration potential may vary within the plant parts at different stages. It has been shown that the chemical composition of crops, and within individual components, changes with the nutrient supplies, thus, in a nutrient deficient soil, nutrient concentration in the plant can vary, creating a deficiency or luxury consumption as is the case of Potassium. The nutrient uptake data gathered in this note is a result of an exhaustive literature review, and is intended to inform the user as to what has been documented. It describes nutrient uptake from major crops grown in the Caribbean Area, Hawaii and the Pacific Basin. Because nutrient uptake is crop, cultivar, site and nutrient content specific, unique values cannot be arbitrarily selected for specific crops. -

Diversidade Genética Molecular Em Germoplasma De Mangueira

1 Universidade de São Paulo Escola Superior de Agricultura “Luiz de Queiroz” Diversidade genética molecular em germoplasma de mangueira Carlos Eduardo de Araujo Batista Tese apresentada para obtenção do título de Doutor em Ciências. Área de concentração: Genética e Melhoramento de Plantas Piracicaba 2013 1 Carlos Eduardo de Araujo Batista Bacharel e Licenciado em Ciências Biológicas Diversidade genética molecular em germoplasma de mangueira versão revisada de acordo com a resolução CoPGr 6018 de 2011 Orientador: Prof. Dr. JOSÉ BALDIN PINHEIRO Tese apresentada para obtenção do título de Doutor em Ciências. Área de concentração: Genética e Melhoramento de Plantas Piracicaba 2013 Dados Internacionais de Catalogação na Publicação DIVISÃO DE BIBLIOTECA - ESALQ/USP Batista, Carlos Eduardo de Araujo Diversidade genética molecular em germoplasma de mangueira / Carlos Eduardo de Araujo Batista.- - versão revisada de acordo com a resolução CoPGr 6018 de 2011. - - Piracicaba, 2013. 103 p: il. Tese (Doutorado) - - Escola Superior de Agricultura “Luiz de Queiroz”, 2013. 1. Diversidade genética 2. Germoplasma vegetal 3. Manga 4. Marcador molecular I. Título CDD 634.441 B333d “Permitida a cópia total ou parcial deste documento, desde que citada a fonte – O autor” 3 Aos meus pais “Francisco e Carmelita”, por todo amor, apoio, incentivo, e por sempre acreditarem em mim... Dedico. Aos meus amigos e colegas, os quais se tornaram parte de minha família... Ofereço. 4 5 AGRADECIMENTOS À Escola Superior de Agricultura “Luiz de Queiroz” (ESALQ/USP) e ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Genética e Melhoramento de Plantas, pela qualidade do ensino e estrutura oferecida e oportunidade de realizar o doutorado. Ao Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) pela concessão de bolsas de estudo Especialmente o Prof. -

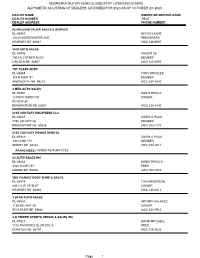

Alphabetical Listing of Dealers Licensed for 2020 As of October 23, 2020

NEBRASKA MOTOR VEHICLE INDUSTRY LICENSING BOARD ALPHABETICAL LISTING OF DEALERS LICENSED FOR 2020 AS OF OCTOBER 23, 2020 DEALER NAME OWNER OR OFFICER NAME DEALER NUMBER TITLE DEALER ADDRESS PHONE NUMBER #2 HAULING TRUCK SALES & SERVICE DL-06965 DEVON LEWIS 10125 SWEETWATER AVE PRES/TREAS KEARNEY NE 68847 (308) 338-9097 14 M AUTO SALES DL-06996 HAIDER ALI 7003 N COTNER BLVD MEMBER LINCOLN NE 68507 (402) 325-8450 1ST CLASS AUTO DL-06388 TONY BUCKLES 358 N MAIN ST MEMBER AINSWORTH NE 69210 (402) 387-2420 2 MEN AUTO SALES DL-05291 DAN R RHILEY 12150 N 153RD CIR OWNER PO BOX 80 BENNINGTON NE 68007 (402) 238-3330 21ST CENTURY EQUIPMENT LLC DL-06065 OWEN A PALM 9738 US HWY 26 MEMBER BRIDGEPORT NE 69336 (308) 262-1110 21ST CENTURY POWER SPORTS DL-05949 OWEN A PALM 1901 LINK 17J MEMBER SIDNEY NE 69162 (308) 254-2511 FRANCHISES: HONDA MOTORCYCLE 24 AUTO SALES INC DL-06268 DANIA PADILLA 3328 S 24TH ST PRES OMAHA NE 68108 (402) 763-1676 2ND CHANCE BODY SHOP & SALES DL-04374 TOM ANDERSON 409 1/2 W 19TH ST OWNER KEARNEY NE 68845 (308) 234-6412 3 STAR AUTO SALES DL-05560 ARTURO VALADEZ 1136 NE HWY 30 OWNER SCHUYLER NE 68661 (402) 352-7912 3-D POWER SPORTS REPAIR & SALES INC DL-07027 DAVID MITCHELL 1108 RIVERSIDE BLVD STE A PRES NORFOLK NE 68701 (402) 316-3633 Page 1 NEBRASKA MOTOR VEHICLE INDUSTRY LICENSING BOARD ALPHABETICAL LISTING OF DEALERS LICENSED FOR 2020 AS OF OCTOBER 23, 2020 DEALER NAME OWNER OR OFFICER NAME DEALER NUMBER TITLE DEALER ADDRESS PHONE NUMBER 308 AUTO SALES DL-06971 STEVE BURNS 908 E 4TH ST OWNER GRAND ISLAND NE 68801 (308) 675-3016 -

To Start Crispy Sushi Rice House Specialties Dessert Cocktails Frozen

executive chef & co-owner chad crete morningside, atl general manager & co-owner anthony vipond cocktails to start WB sour* 9 yakitori • \yah-kih-tohr-ee\ bourbon, housemade sour our spin on the japanese tradition of grilled bites on a skewer mix choose four 15 whole shebang 25 margarita* 9 blanco tequila, housemade sticky chicken mushroom sweet potato octopus & sausage sour mix crispy meatball chimichurri shrimp stuffed peppers moscow mule 9 dip duo korean queso & yuzu guacamole, wonton chips 12 vodka, ginger beer gyoza tacos spicy ahi tuna*, cucumber, avocado, mango 7 peruvian chicken, salsa verde, cotjia cheese 6 sloe gin fizz* 9 hong kong slider buttermilk fried chicken, pickles, wb sauce 7 sloe gin, citrus, soda whole roasted cauliflower smoked gouda fondue, everything bagel seasoning, herbs 14 old fashioned 12 bourbon, bitters crispy brussels fried egg, bacon, maple syrup, chinese vinegar, wb sauce, bonito flakes 14 gimlet 12 housemade lime cordial gin OR vodka crispy sushi rice spicy mexico city 12 four pieces of sushi rice crisped into delicious golden brown cakes & topped with the listed ingredients tequila, jalapeno, lime, lime cordial, salt rim spicy tuna* mango, cucumber, avocado, jalapeno, wb sauce, takoyaki 15 manhattan 12 smoked salmon yuzu tartare, chives, dill, chile oil 14 rye, sweet vermouth crunchy shrimp macadamia nut, toasted coconut, avocado, mango sauce, yuzu tartare 14 rose 75 12 umami bomb pickled shiitake, carrot, avocado, sundried tomato, wb sauce, takoyaki 13 pink gin, fresh grapefruit, bubbly brown derby -

Papaya, Mango and Guava Fruit Metabolism During Ripening: Postharvest Changes Affecting Tropical Fruit Nutritional Content and Quality

® Fresh Produce ©2010 Global Science Books Papaya, Mango and Guava Fruit Metabolism during Ripening: Postharvest Changes Affecting Tropical Fruit Nutritional Content and Quality João Paulo Fabi* • Fernanda Helena Gonçalves Peroni • Maria Luiza Passanezi Araújo Gomez Laboratório de Química, Bioquímica e Biologia Molecular de Alimentos, Departamento de Alimentos e Nutrição Experimental, FCF, Universidade de São Paulo, Avenida Lineu Prestes 580, Bloco 14, CEP 05508-900, São Paulo – SP, Brazil Corresponding author : * [email protected] ABSTRACT The ripening process affects the nutritional content and quality of climacteric fruits. During papaya ripening, papayas become more acceptable due to pulp sweetness, redness and softness, with an increment of carotenoids. Mangoes increase the strong aroma, sweetness and vitamin C, -carotene and minerals levels during ripening. Ripe guavas have one of the highest levels of vitamin C and minerals compared to other tropical fleshy fruits. Although during these fleshy fruit ripening an increase in nutritional value and physical-chemical quality is observed, these changes could lead to a reduced shelf-life. In order to minimize postharvest losses, some techniques have been used such as cold storage and 1-MCP treatment. The techniques are far from being standardized, but some interesting results have been achieved for papayas, mangoes and guavas. Therefore, this review focuses on the main changes occurring during ripening of these three tropical fruits that lead to an increment of quality attributes and nutritional -

Collier Fruit Growers Newsletter May 2015

COLLIER FRUIT GROWERS NEWSLETTER MAY 2015 The May 18th Speaker is Dr. Doug “Dougbug” Caldwell . Doug Caldwell will present and discuss his concept of a Collier Fruit Initiative as well as current invasive pests of Southwest Florida. DougBug is the go-to person on insects in Collier County and has a heart to promote fruit trees comfortable with our unique climate. DougBug is the commercial horticulturalist, entomologist and certified arborist at the UF/IFAS Collier County extension office. Next Meeting is May 18 at the Golden Gate Community Center, 4701 Golden Gate Parkway 7:00 pm for the tasting table and 7:30 pm for the meeting/program. BURDS’ NEST OF INFORMATION THIS and THAT FOR MAY: MANGOS: Now that the mango season is commencing, LATE mangos should be selectively pruned, (yes - there will be fruit on the tree) so as to have fruit again next year. Selectively pruning, so as not to lose all the fruit. If late mangos are pruned after the fruit is harvested, eg: late September or October, it raises the % chance of no fruit the next year. Late mangos are Keitt, Neelum, Palmer, Beverly, Wise, Cryder & Zillate Early mangos – Rosigold, Lemon Saigon, Glen, Manilita & Florigon, to name just a few! When the fruit has been harvested, fertilize with 0-0-18. This is recommended because of the minors in the formulae. Fertilizing with nitrogen will cause ‘jelly seed’ and poor quality fruit. Also, spray with micro nutrients just before the new growth has hardened off. Page 2 COLLIER FRUIT GROWERS NEWSLETTER RECIPE OF THE MONTH Meyer lemons are believed to be a natural hybrid of a lemon and a sweet orange. -

International Cooperation Among Botanic Gardens

INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AMONG BOTANIC GARDENS: THE CONCEPT OF ESTABLISHING AGREEMENTS By Erich S. Rudyj A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the University of elaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Science in Public Horticulture Administration May 1988 © 1988 Erich S. Rudyj INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION~ AMONG BOTANIC GARDENS: THE CONCEPT OF EsrtBllSHING AGREEMENTS 8y Erich S. Rudyj Approved: _ James E. Swasey, Ph.D. Professor in charge of thesis on behalf of the Advisory Committee Approved: _ James E. Swasey, Ph.D. Coordinator of the Longwood Graduate Program Approved: _ Richard 8. MLfrray, Ph.D. Associate Provost for Graduate Studies No man is an /land, intire of it selfe; every man is a peece of the Continent, a part of the maine; if a Clod bee washed away by the Sea, Europe is the lesse, as well as if a Promontorie '-"Jere, as well as if a Mannor of thy friends or of thine owne were; any mans death diminishes me, because I am involved in Mankinde; And therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls; It tolls for thee. - JOHN DONNE - In the Seventeenth Meditation of the Devotions Upon Emergent Occasions (1624) iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to express my sincerest thanks to Donald Crossan, James Oliver and James Swasey, who, as members of my thesis committee, provided me with the kind of encouragement and guidance needed to merge both the fields of Public Horticulture and International Affairs. Special thanks are extended to the organizers and participants of the Tenth General Meeting and Conference of the International Association of Botanical Gardens (IABG) for their warmth, advice and indefatigable spirit of international cooperation. -

Effect of Fruit Thinning on 'Sensation' Mango (Mangifera Indica) Trees With

University of Pretoria etd – Yeshitela, T B (2004) CHAPTER 3 EFFECT OF FRUIT THINNING ON ‘SENSATION’ MANGO (MANGIFERA INDICA) TREES WITH RESPECT TO FRUIT QUALITY, QUANTITY AND TREE PHENOLOGY. 3.1 ABSTRACT Different fruit thinning methods (various intensities in manual fruit thinning as well as a chemical thinner) were tested on ‘Sensation’ mango trees both as initial and cumulative effects during two seasons (2001/2002 and 2002/2003). The trial was conducted at Bavaria Estate, in the Hoedspruit area, Northern Province of South Africa. The thinning treatments were carried out in October before the occurrence of excessive natural fruit drop. The objective of the study was to select the best thinning intensity or method, based on their impacts on different parameters. Where fruit on ‘Sensation’ were thinned to one and two fruit per panicle, a significant increase was obtained for most of the fruit quantitative yield parameters. With the treatments where one fruit and two fruit per panicle were retained and 50% of the panicles removed, a significant increase in fruit size was noted. The same trees also produced higher figures for most of the fruit qualitative parameters as well as fruit retention percentage. However, the trend showed that bigger sized fruit were prone to a higher incidence of physiological problems, especially jelly seed. Chemical fruit thinning with Corasil.E produced very small sized fruit with a considerable percentage of “mules” 43 University of Pretoria etd – Yeshitela, T B (2004) (fruit without seed). Trees subjected to severe thinning intensities showed earlier revival of starch reserves and better vegetative growth. Key words: fruit per panicle, fruit quantity, fruit quality • Published in Experimental Agriculture, vol 40(4), pp. -

Flowering Synchronization of Sensation Mango Trees by Winter Pruning

Flowering Synchronization of Sensation Mango Trees by Winter Pruning S.A. Oosthuyse and G. Jacobs Horticultural Science, University of Stellenbosch, Stellenbosch 7600 ABSTRACT To synchronize flowering, all of the terminal shoots on separate sets of Sensation mango trees were pruned on a number dates occurring just prior to and during the flowering period. Pruning was performed 5 em beneath the site of apical bud or inflorescence attachment or at this site. Only trees in their 'on' year were pruned. Flowering was effectively delayed in accordance with pruning date due to the consequent development of axillary inflorescences beneath the pruning cuts. Flowering was synchronized, and resulted in a reduction in variability of the stage of fruit maturation at harvest. Flowering intensity was increased by winter pruning due to the enhanced number of inflorescences developing per terminal shoot. Fruit drop was also increased. Tree yield was unaffected due to a compensatory increase in fruit size. Stage of fruit maturation at harvest and time of flowering were inversely related. A reduction in fruit retention and tree yield was associated with pruning the terminal shoots 5 em beneath the site of apical bud or inflorescence attachment, as opposed to at this site. Our results show that winter pruning can be recommended as a measure to synchronize the flowering of Sensation mango trees when the trees are in a positive phase of bearing alternation. ering period, as a measure to reduce variability of flowering and of the degree of maturation at harvest. Assessment was In mango, the removal of the apical bud or inflorescence also made of the effect of winter pruning on the time and on terminal shoots just prior to or during the flowering intensity of flowering, on fruit retention, and on tree yield period ('winter pruning') results in the development of at harvest.