Leadership and Ethical Development: Balancing Light and Shadow

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 'Van Dyke' Mango

7. MofTet, M. L. 1973. Bacterial spot of stone fruit in Queensland. 12. Sherman, W. B., C. E. Yonce, W. R. Okie, and T. G. Beckman. Australian J. Biol. Sci. 26:171-179. 1989. Paradoxes surrounding our understanding of plum leaf scald. 8. Sherman, W. B. and P. M. Lyrene. 1985. Progress in low-chill plum Fruit Var. J. 43:147-151. breeding. Proc. Fla. State Hort. Soc. 98:164-165. 13. Topp, B. L. and W. B. Sherman. 1989. Location influences on fruit 9. Sherman, W. B. and J. Rodriquez-Alcazar. 1987. Breeding of low- traits of low-chill peaches in Australia. Proc. Fla. State Hort. Soc. chill peach and nectarine for mild winters. HortScience 22:1233- 102:195-199. 1236. 14. Topp, B. L. and W. B. Sherman. 1989. The relationship between 10. Sherman, W. B. and R. H. Sharpe. 1970. Breeding plums in Florida. temperature and bloom-to-ripening period in low-chill peach. Fruit Fruit Var. Hort. Dig. 24:3-4. Var.J. 43:155-158. 11. Sherman, W. B. and B. L. Topp. 1990. Peaches do it with chill units. Fruit South 10(3): 15-16. Proc. Fla. State Hort. Soc. 103:298-299. 1990. THE 'VAN DYKE' MANGO Carl W. Campbell History University of Florida, I FAS Tropical Research and Education Center The earliest records we were able to find on the 'Van Homestead, FL 33031 Dyke' mango were in the files of the Variety Committee of the Florida Mango Forum. They contain the original de scription form, quality evaluations dated June and July, Craig A. -

To Clarify These Terms, Our Discussion Begins with Hydraulic Conductivity Of

Caribbean Area PO BOX 364868 San Juan, PR 00936-4868 787-766-5206 Technology Transfer Technical Note No. 2 Tropical Crops & Forages Nutrient Uptake Purpose The purpose of this technical note is to provide guidance in nutrient uptake values by tropical crops in order to make fertilization recommendations and nutrient management. Discussion Most growing plants absorb nutrients from the soil. Nutrients are eventually distributed through the plant tissues. Nutrients extracted by plants refer to the total amount of a specific nutrient uptake and is the total amount of a particular nutrient needed by a crop to complete its life cycle. It is important to clarify that the nutrient extraction value may include the amount exported out of the field in commercial products such as; fruits, leaves or tubers or any other part of the plant. Nutrient extraction varies with the growth stage, and nutrient concentration potential may vary within the plant parts at different stages. It has been shown that the chemical composition of crops, and within individual components, changes with the nutrient supplies, thus, in a nutrient deficient soil, nutrient concentration in the plant can vary, creating a deficiency or luxury consumption as is the case of Potassium. The nutrient uptake data gathered in this note is a result of an exhaustive literature review, and is intended to inform the user as to what has been documented. It describes nutrient uptake from major crops grown in the Caribbean Area, Hawaii and the Pacific Basin. Because nutrient uptake is crop, cultivar, site and nutrient content specific, unique values cannot be arbitrarily selected for specific crops. -

Diversidade Genética Molecular Em Germoplasma De Mangueira

1 Universidade de São Paulo Escola Superior de Agricultura “Luiz de Queiroz” Diversidade genética molecular em germoplasma de mangueira Carlos Eduardo de Araujo Batista Tese apresentada para obtenção do título de Doutor em Ciências. Área de concentração: Genética e Melhoramento de Plantas Piracicaba 2013 1 Carlos Eduardo de Araujo Batista Bacharel e Licenciado em Ciências Biológicas Diversidade genética molecular em germoplasma de mangueira versão revisada de acordo com a resolução CoPGr 6018 de 2011 Orientador: Prof. Dr. JOSÉ BALDIN PINHEIRO Tese apresentada para obtenção do título de Doutor em Ciências. Área de concentração: Genética e Melhoramento de Plantas Piracicaba 2013 Dados Internacionais de Catalogação na Publicação DIVISÃO DE BIBLIOTECA - ESALQ/USP Batista, Carlos Eduardo de Araujo Diversidade genética molecular em germoplasma de mangueira / Carlos Eduardo de Araujo Batista.- - versão revisada de acordo com a resolução CoPGr 6018 de 2011. - - Piracicaba, 2013. 103 p: il. Tese (Doutorado) - - Escola Superior de Agricultura “Luiz de Queiroz”, 2013. 1. Diversidade genética 2. Germoplasma vegetal 3. Manga 4. Marcador molecular I. Título CDD 634.441 B333d “Permitida a cópia total ou parcial deste documento, desde que citada a fonte – O autor” 3 Aos meus pais “Francisco e Carmelita”, por todo amor, apoio, incentivo, e por sempre acreditarem em mim... Dedico. Aos meus amigos e colegas, os quais se tornaram parte de minha família... Ofereço. 4 5 AGRADECIMENTOS À Escola Superior de Agricultura “Luiz de Queiroz” (ESALQ/USP) e ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Genética e Melhoramento de Plantas, pela qualidade do ensino e estrutura oferecida e oportunidade de realizar o doutorado. Ao Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) pela concessão de bolsas de estudo Especialmente o Prof. -

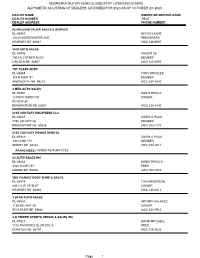

Alphabetical Listing of Dealers Licensed for 2020 As of October 23, 2020

NEBRASKA MOTOR VEHICLE INDUSTRY LICENSING BOARD ALPHABETICAL LISTING OF DEALERS LICENSED FOR 2020 AS OF OCTOBER 23, 2020 DEALER NAME OWNER OR OFFICER NAME DEALER NUMBER TITLE DEALER ADDRESS PHONE NUMBER #2 HAULING TRUCK SALES & SERVICE DL-06965 DEVON LEWIS 10125 SWEETWATER AVE PRES/TREAS KEARNEY NE 68847 (308) 338-9097 14 M AUTO SALES DL-06996 HAIDER ALI 7003 N COTNER BLVD MEMBER LINCOLN NE 68507 (402) 325-8450 1ST CLASS AUTO DL-06388 TONY BUCKLES 358 N MAIN ST MEMBER AINSWORTH NE 69210 (402) 387-2420 2 MEN AUTO SALES DL-05291 DAN R RHILEY 12150 N 153RD CIR OWNER PO BOX 80 BENNINGTON NE 68007 (402) 238-3330 21ST CENTURY EQUIPMENT LLC DL-06065 OWEN A PALM 9738 US HWY 26 MEMBER BRIDGEPORT NE 69336 (308) 262-1110 21ST CENTURY POWER SPORTS DL-05949 OWEN A PALM 1901 LINK 17J MEMBER SIDNEY NE 69162 (308) 254-2511 FRANCHISES: HONDA MOTORCYCLE 24 AUTO SALES INC DL-06268 DANIA PADILLA 3328 S 24TH ST PRES OMAHA NE 68108 (402) 763-1676 2ND CHANCE BODY SHOP & SALES DL-04374 TOM ANDERSON 409 1/2 W 19TH ST OWNER KEARNEY NE 68845 (308) 234-6412 3 STAR AUTO SALES DL-05560 ARTURO VALADEZ 1136 NE HWY 30 OWNER SCHUYLER NE 68661 (402) 352-7912 3-D POWER SPORTS REPAIR & SALES INC DL-07027 DAVID MITCHELL 1108 RIVERSIDE BLVD STE A PRES NORFOLK NE 68701 (402) 316-3633 Page 1 NEBRASKA MOTOR VEHICLE INDUSTRY LICENSING BOARD ALPHABETICAL LISTING OF DEALERS LICENSED FOR 2020 AS OF OCTOBER 23, 2020 DEALER NAME OWNER OR OFFICER NAME DEALER NUMBER TITLE DEALER ADDRESS PHONE NUMBER 308 AUTO SALES DL-06971 STEVE BURNS 908 E 4TH ST OWNER GRAND ISLAND NE 68801 (308) 675-3016 -

Papaya, Mango and Guava Fruit Metabolism During Ripening: Postharvest Changes Affecting Tropical Fruit Nutritional Content and Quality

® Fresh Produce ©2010 Global Science Books Papaya, Mango and Guava Fruit Metabolism during Ripening: Postharvest Changes Affecting Tropical Fruit Nutritional Content and Quality João Paulo Fabi* • Fernanda Helena Gonçalves Peroni • Maria Luiza Passanezi Araújo Gomez Laboratório de Química, Bioquímica e Biologia Molecular de Alimentos, Departamento de Alimentos e Nutrição Experimental, FCF, Universidade de São Paulo, Avenida Lineu Prestes 580, Bloco 14, CEP 05508-900, São Paulo – SP, Brazil Corresponding author : * [email protected] ABSTRACT The ripening process affects the nutritional content and quality of climacteric fruits. During papaya ripening, papayas become more acceptable due to pulp sweetness, redness and softness, with an increment of carotenoids. Mangoes increase the strong aroma, sweetness and vitamin C, -carotene and minerals levels during ripening. Ripe guavas have one of the highest levels of vitamin C and minerals compared to other tropical fleshy fruits. Although during these fleshy fruit ripening an increase in nutritional value and physical-chemical quality is observed, these changes could lead to a reduced shelf-life. In order to minimize postharvest losses, some techniques have been used such as cold storage and 1-MCP treatment. The techniques are far from being standardized, but some interesting results have been achieved for papayas, mangoes and guavas. Therefore, this review focuses on the main changes occurring during ripening of these three tropical fruits that lead to an increment of quality attributes and nutritional -

Collier Fruit Growers Newsletter May 2015

COLLIER FRUIT GROWERS NEWSLETTER MAY 2015 The May 18th Speaker is Dr. Doug “Dougbug” Caldwell . Doug Caldwell will present and discuss his concept of a Collier Fruit Initiative as well as current invasive pests of Southwest Florida. DougBug is the go-to person on insects in Collier County and has a heart to promote fruit trees comfortable with our unique climate. DougBug is the commercial horticulturalist, entomologist and certified arborist at the UF/IFAS Collier County extension office. Next Meeting is May 18 at the Golden Gate Community Center, 4701 Golden Gate Parkway 7:00 pm for the tasting table and 7:30 pm for the meeting/program. BURDS’ NEST OF INFORMATION THIS and THAT FOR MAY: MANGOS: Now that the mango season is commencing, LATE mangos should be selectively pruned, (yes - there will be fruit on the tree) so as to have fruit again next year. Selectively pruning, so as not to lose all the fruit. If late mangos are pruned after the fruit is harvested, eg: late September or October, it raises the % chance of no fruit the next year. Late mangos are Keitt, Neelum, Palmer, Beverly, Wise, Cryder & Zillate Early mangos – Rosigold, Lemon Saigon, Glen, Manilita & Florigon, to name just a few! When the fruit has been harvested, fertilize with 0-0-18. This is recommended because of the minors in the formulae. Fertilizing with nitrogen will cause ‘jelly seed’ and poor quality fruit. Also, spray with micro nutrients just before the new growth has hardened off. Page 2 COLLIER FRUIT GROWERS NEWSLETTER RECIPE OF THE MONTH Meyer lemons are believed to be a natural hybrid of a lemon and a sweet orange. -

International Cooperation Among Botanic Gardens

INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AMONG BOTANIC GARDENS: THE CONCEPT OF ESTABLISHING AGREEMENTS By Erich S. Rudyj A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the University of elaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Science in Public Horticulture Administration May 1988 © 1988 Erich S. Rudyj INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION~ AMONG BOTANIC GARDENS: THE CONCEPT OF EsrtBllSHING AGREEMENTS 8y Erich S. Rudyj Approved: _ James E. Swasey, Ph.D. Professor in charge of thesis on behalf of the Advisory Committee Approved: _ James E. Swasey, Ph.D. Coordinator of the Longwood Graduate Program Approved: _ Richard 8. MLfrray, Ph.D. Associate Provost for Graduate Studies No man is an /land, intire of it selfe; every man is a peece of the Continent, a part of the maine; if a Clod bee washed away by the Sea, Europe is the lesse, as well as if a Promontorie '-"Jere, as well as if a Mannor of thy friends or of thine owne were; any mans death diminishes me, because I am involved in Mankinde; And therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls; It tolls for thee. - JOHN DONNE - In the Seventeenth Meditation of the Devotions Upon Emergent Occasions (1624) iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to express my sincerest thanks to Donald Crossan, James Oliver and James Swasey, who, as members of my thesis committee, provided me with the kind of encouragement and guidance needed to merge both the fields of Public Horticulture and International Affairs. Special thanks are extended to the organizers and participants of the Tenth General Meeting and Conference of the International Association of Botanical Gardens (IABG) for their warmth, advice and indefatigable spirit of international cooperation. -

Download the Carlisle ELECTRICAL & WIRING TREASURED MOTORCAR SERVICES RED BEARDS TOOLS Events App for Iphone and L 195-198, M 196-199 Android

OFFICIAL EVENT GUIDE Contents WORLD’S FINEST CAR SHOWS & AUTOMOTIVE EVENTS 5 WELCOME 7 FORD MOTOR COMPANY 9 SPECIAL GUESTS 10 EVENT HIGHLIGHTS 15 WOMEN’S OASIS 2019-2020 EVENT SCHEDULE 17 NPD SHOWFIELD HIGHLIGHTS JAN. 18-20, 2019 FEATURED VEHICLE DISPLAYS: AUTO MANIA 19 FORD GT PROTOTYPE ALLENTOWN PA FAIRGROUNDS JAN. 17-19, 2020 FEATURED VEHICLE DISPLAY: FEB. 22-24, 2019 21 FORD NATIONALS SELECT WINTER AUTOFEST LAKELAND SUN ’n FUN, LAKELAND, FL FEB. 21-23, 2020 FEATURED VEHICLE DISPLAY: 22 40 YEARS OF THE FOX BODY LAKELAND WINTER FEB. 22-23, 2019 COLLECTOR CAR AUCTION FEATURED VEHICLE DISPLAY: SUN ’n FUN, LAKELAND, FL FEB. 21-22, 2020 25 50 YEARS OF THE MACH 1 APRIL 24-28, 2019 FEATURED VEHICLE DISPLAY: SPRING CARLISLE CARLISLE PA FAIRGROUNDS 26 50 YEARS OF THE BOSS APRIL 22-26, 2020 FEATURED VEHICLE DISPLAY: SPRING CARLISLE APRIL 25-26, 2019 29 50 YEARS OF THE ELIMINATOR COLLECTOR CAR AUCTION CARLISLE EXPO CENTER APRIL 23-24, 2020 29 SOCIAL STOPS IMPORT & PERFORMANCE MAY 17-19, 2019 EVENT MAP NATIONALS 20 CARLISLE PA FAIRGROUNDS MAY 15-17, 2020 19 EVENT SCHEDULE FORD NATIONALS MAY 31-JUNE 2, 2019 PRESENTED BY MEGUIAR’S 34 GUEST SPOTLIGHT CARLISLE PA FAIRGROUNDS JUNE 5-7, 2020 37 SUMMER OF ’69 CHEVROLET NATIONALS JUNE 21-22, 2019 CARLISLE PA FAIRGROUNDS 39 VENDORS: BY SPECIALTY JUNE 26-27, 2020 CARLISLE AUCTIONS JUNE 22, 2019 43 VENDORS: A-Z SUMMER SALE CARLISLE EXPO CENTER JUNE 27, 2020 48 ABOUT OUR PARTNERS JULY 12-14, 2019 CARLISLE FAIRGROUNDS CHRYSLER NATIONALS 51 POLICIES & INFORMATION CARLISLE PA FAIRGROUNDS JULY 10-12, 2020 53 CONCESSIONS TRUCK NATIONALS AUG. -

Gregory, Bruce

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project BRUCE GREGORY Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial interview date: January 5, 2006 Copyright 2015 ADST TABLE OF CONTENTS Background Born and raised in Rhode Island Barrington College, American University USIA’s Historical Office 1967-1970 Research on USIA’s pre-WWII origins Monograph on US international broadcasting USIA 1970-1978 Book programs Speaker programs Young Officers Policy Panel AFGE Local 1812 Thomas Legal Defense Fund Foreign Affairs Specialist lawsuit, AFGE v. Keogh Selection out due process lawsuit, Lindsey v. Kissinger E.O. 11636, FS employee-management system Foreign Service representation election in USIA Collective bargaining in USIA Dante Fascell, hearings on Stanton Panel report Congressional Fellowship, Mo Udall, Carl Levin 1978-1979 Udall re-election campaign Panama Canal Treaty implementing legislation Detail to USIS New Delhi US Advisory Commission on Public Diplomacy 1980-1998 Carter administration, Olin Robison US International Communication Agency Reagan administration, Edwin J. Feulner Annual reports Reports on summit diplomacy, Soviet Union, China Report on public diplomacy and terrorism 1 USIA Director Charles Z. Wick Peter Galbraith’s interest in the Commission George H. W. Bush administration, Tom Korologos Commission opposition to TV Marti Views on US broadcasting after the Cold War Commission opposition to Radio Free Asia Clinton administration, Lewis Manilow, Harold Pachios Senator Jesse Helms and foreign -

María José Grajal Martín Instituto Canario De Investigaciones Agrarias ICIA Botánica

María José Grajal Martín Instituto Canario de Investigaciones Agrarias ICIA www.icia.es Botánica Orden: Sapindales Familia: Anacardiaceae Género: Mangifera Especie: Mangifera indica L. Nombre común: mango En Canarias a veces mango (fibras) y manga (sin fibras) María José Grajal Martín. Instituto Canario de Investigaciones Agrarias. 18 de Enero 2016. Cabildo de Lanzarote. Área de Agricultura y Ganadería. M. casturi M. zeylanica M. laurina M. odorata 18 de Enero 2016. Cabildo de Lanzarote. Área de Agricultura y Ganadería. Centro Origen Noroeste de Myamar (Birmania), Bangladesh, y Noreste de India 18 de Enero 2016. Cabildo de Lanzarote. Área de Agricultura y Ganadería. Dispersión India: Cultivo hace más de 4000 años China e Indochina <s.VII Comerciantes árabes a África via Persia y Arabia siglo X Siglos XV y XVI europeos en sus viajes de colonización. Portugueses desde sus colonias en India a sus colonias de África (Angola y Mozambique) y a Brasil Españoles tipos poliembriónicos de Filipinas a América (México cv Manila). Antillas XVIII desde Brasil Transporte Semillas recalcitrantes Frutos fresco, plántulas ó plantas injertadas 18 de Enero 2016. Cabildo de Lanzarote. Área de Agricultura y Ganadería. Florida USA 1861 (desde Cuba No. 11) 1868 ᶦPeachᶦ ᶦMulgobaᶦ (India) primeras plantaciones comerciales origen ᶦHadenᶦ (1910) ᶦHadenᶦ ᶦMulgobaᶦ 18 de Enero 2016. Cabildo de Lanzarote. Área de Agricultura y Ganadería. Florida Introducción de material procedente de India, Filipinas.... Desarrollo de un intenso programa de mejora India: ᶦMulgobaᶦ, ᶦSandershaᶦ, ᶦAminiᶦ y ᶦBombayᶦ Antillas: ᶦTurpentineᶦ cv Osteen Desarrollo de la mayoría de los cultivares comerciales de mango: ᶦKeittᶦ , ᶦLippensᶦ, ᶦOsteenᶦ, ᶦTommy Atkinsᶦ, ᶦZillᶦ, etc. cv. -

White Sapote

Bonita Springs Tropical Fruit Club Inc. PO Box 367791 Bonita Springs, FL 34136 May 2015 - White Sapote Bonita Springs Tropical Fruit Club Newsletter Who we are and what we do: The Bonita Springs Tropical Fruit Club, Inc., is an educational not-for-profit organization whose purpose is to inform, educate and advise members and the public in the selection of plants and trees, to encour- age their cultivation, and to provide a social forum where members can freely exchange plant material and information. The club cooperates with many organizations, and provides a basis for producing new cultivars. We function in any legal manner to further the above stated aims. Meetings: Regular membership meetings that include an educational program are held the second Tuesday of each month, except July and August. Meetings begin promptly at 7 PM, at the First United Methodist Church, 27690 Shriver Avenue, Bonita Springs. The meetings are held in the "Fellowship Hall" meeting room. Workshops: Workshops (monthly discussions) are held on the fourth Tuesday of each month at 7 PM at the Method- ist Church, when practical. This open format encourages discussion and sharing of fruits and informa- tion. Bring in your fruits, plants, seeds, leaves, insects, photos, recipes, ect.. This is a great chance to get answers to specific questions, and there always seems to be a local expert on hand! Tree sale: Semi-annual tree sales in February and November at Riverside Park in downtown Bonita Springs raise revenue for educational programs for club members and other related purposes of the club. Trips: The club occasionally organizes trips and tours of other organizations that share our interests. -

The Florida East Coast Homeseeker, 1913 (Image Courtesy of the City Through Everglades National Park

A PUBLICATION OF THE BROWARD COUNTY HISTORICAL COMMISSION volume 29 • number 1 • 2009 Getting the Bugs Out: Fort Lauderdale before pest control Transcriptions of The Homeseeker Parkside: An early neighborhood in Hollywood worthy of historic designation West Side School: West Side Elementary School First Grade Class, 1923 86 Years of serving Broward County (Image courtesy of the Fort Lauderdale Historical Society) Curcie House, circa 1920s You Can Help Save History from the Dust Heap. Each day more of our local history is lost by the passage of time, the passing of early pioneers, and the loss of historic and archaeological sites throughout Broward County. But you can help. The Broward County Historical Commission has been working to preserve local history since 1972 with help from people like you. By donating old family photos and documents, volunteering at events, and providing donations to the Broward County Historical Commission Trust Fund, your efforts help preserve our history. Consider how you can help save our heritage and create a legacy for your community by contributing your time, historical items, or your generosity. What you do today maintains the dignity of history for the future. Call us at 954-357-5553. Monetary donations may be made to: Broward County Historical Commission Trust Fund 301 S.W. 13th Avenue Fort Lauderdale, Florida 33312 Detail of the West Side School. A PUBLICATION OF THE BROWARD COUNTY HISTORICAL COMMISSION A SERVICE OF THE BROWARD COUNTY BOARD OF COUNTY COMMISSIONERS Bertha Henry County Administrator BROWARD COUNTY HISTORICAL volume 29 • number 1 • 2009 COMMISSIONERS Phyllis Loconto, Chair Hazel K.