The Guide: Adaptation from Novel to Film

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Movie Aquisitions in 2010 - Hindi Cinema

Movie Aquisitions in 2010 - Hindi Cinema CISCA thanks Professor Nirmal Kumar of Sri Venkateshwara Collega and Meghnath Bhattacharya of AKHRA Ranchi for great assistance in bringing the films to Aarhus. For questions regarding these acquisitions please contact CISCA at [email protected] (Listed by title) Aamir Aandhi Directed by Rajkumar Gupta Directed by Gulzar Produced by Ronnie Screwvala Produced by J. Om Prakash, Gulzar 2008 1975 UTV Spotboy Motion Pictures Filmyug PVT Ltd. Aar Paar Chak De India Directed and produced by Guru Dutt Directed by Shimit Amin 1954 Produced by Aditya Chopra/Yash Chopra Guru Dutt Production 2007 Yash Raj Films Amar Akbar Anthony Anwar Directed and produced by Manmohan Desai Directed by Manish Jha 1977 Produced by Rajesh Singh Hirawat Jain and Company 2007 Dayal Creations Pvt. Ltd. Aparajito (The Unvanquished) Awara Directed and produced by Satyajit Raj Produced and directed by Raj Kapoor 1956 1951 Epic Productions R.K. Films Ltd. Black Bobby Directed and produced by Sanjay Leela Bhansali Directed and produced by Raj Kapoor 2005 1973 Yash Raj Films R.K. Films Ltd. Border Charulata (The Lonely Wife) Directed and produced by J.P. Dutta Directed by Satyajit Raj 1997 1964 J.P. Films RDB Productions Chaudhvin ka Chand Dev D Directed by Mohammed Sadiq Directed by Anurag Kashyap Produced by Guru Dutt Produced by UTV Spotboy, Bindass 1960 2009 Guru Dutt Production UTV Motion Pictures, UTV Spot Boy Devdas Devdas Directed and Produced by Bimal Roy Directed and produced by Sanjay Leela Bhansali 1955 2002 Bimal Roy Productions -

Bollywood in Australia: Transnationalism and Cultural Production

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Arts - Papers (Archive) Faculty of Arts, Social Sciences & Humanities 1-1-2010 Bollywood in Australia: Transnationalism and Cultural Production Andrew Hassam University of Wollongong, [email protected] Makand Maranjape Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/artspapers Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Hassam, Andrew and Maranjape, Makand, Bollywood in Australia: Transnationalism and Cultural Production 2010. https://ro.uow.edu.au/artspapers/258 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Introduction Bollywood in Australia Andrew Hassam and Makand Paranjape The global context of Bollywood in Australia Makarand Paranjape The transcultural character and reach of Bollywood cinema has been gradually more visible and obvious over the last two decades. What is less understood and explored is its escalating integration with audiences, markets and entertainment industries beyond the Indian subcontinent. This book explores the relationship of Bollywood to Australia. We believe that this increasingly important relationship is an outcome of the convergence between two remarkably dynamic entities—globalising Bollywood, on the one hand and Asianising Australia, on the other. If there is a third element in this relationship, which is equally important, it is the mediating power of the vibrant diasporic community of South Asians in Australia. Hence, at its most basic, this book explores the conjunctures and ruptures between these three forces: Bollywood, Australia and their interface, the diaspora. 1 Bollywood in Australia It would be useful to see, at the outset, how Bollywood here refers not only to the Bombay film industry, but is symbolic of the Indian and even the South Asian film industry. -

Institute of Film & Video Technology, Mumbai

INSTITUTE OF FILM & VIDEO TECHNOLOGY, MUMBAI & MEWAR UNIVERSITY, CHITTORGARH (Rajasthan) PROSPECTUS for JOINT PROGRAMMES ABOUT THE IFVT: There has always been a mad rush of people aspiring to join the glamour world of Cinema and Television. However, there is no clear cut path carved out for their entry other than through the Film Institutes established by the Government. There is always a need felt by the Production Houses to have trained film makers and technicians for quality film and Television productions. Considering this huge requirement of trained professionals many private institutes have mushroomed in various places. However these Institutes also lack the trained faculty in various departments of film making. This has prompted few graduates from Film and Television Institutes of India to come together and thus the Institute of Film and Video Technology was established with a sole objective of providing professional education in Cinema and Television Technology. The IFVT endeavors to take Cinema Education to the places where Cinema is not made and Cinema is not taught. IFVT opens a window of opportunities to those who have no access to the world of Cinema. OUR MISSION: To strive to give Cinema Education a Professional status Equivalent to other professional Degrees such as Medical, Engineering, Computers etc by providing a Bachelors degree in Cinema & Television with Master’s degree & PhD in cinema thereafter. FACILITIES AND SERVICES: IFVT draws its highly experienced faculty from internationally renowned Film Institutes and from the film industry. Apart from the permanent faculty, the IFVT has tie ups and arrangements with reputed artistes and technicians from the film world to train & share their experiences with the students. -

The Seductive Voice

> The art of seduction The seductive voice Charles Darwin had no doubts about the origins of music – it was a kind of mating call, a primitive language of the emotions from an early stage of evolution. While his ideas about music and evolution have often been alluded to, Darwin never really paid much attention to music. His contemporary Herbert Spencer, who was much more conversant with music, saw it differently – music had evolved from language, in particular speech laden with emotion. Wim van der Meer tic and the texts always had something to do with love. But their greatest asset was their voice. The best singers were (and iscussion on the origins of music and its evolutionary are) capable of captivating their audience with magical Dsignificance has regained momentum over the past magnetism. decade and a half. Nils Wallin, Ian Cross, Steven Mithen and Björn Merker are among those who have given impetus to this In my personal contact with some of the great women singers field of research referred to as biomusicology. Others oppose of India, I have been struck by how powerful the voice can be. the idea of music as important to evolution. Steven Pinker, for It is enough for them to barely utter a few sounds and one can- instance, considers music a useless, though pleasant, side- not escape the attraction. It is some indefinable quality of the product of language that could just as well be eliminated from voice, openness of the sound, and an earthy sensuality. Of human existence. course this is not limited to Indian courtesans. -

Research Paper Impact Factor

Research Paper IJBARR Impact Factor: 3.072 E- ISSN -2347-856X Peer Reviewed, Listed & Indexed ISSN -2348-0653 HISTORY OF INDIAN CINEMA Dr. B.P.Mahesh Chandra Guru * Dr.M.S.Sapna** M.Prabhudev*** Mr.M.Dileep Kumar**** * Professor, Dept. of Studies in Communication and Journalism, University of Mysore, Manasagangotri, Karnataka, India. **Assistant Professor, Department of Studies in Communication and Journalism, University of Mysore, Manasagangotri, Karnataka, India. ***Research Scholar, Department of Studies in Communication and Journalism, University of Mysore, Manasagangotri, Karnataka, India. ***RGNF Research Scholar, Department of Studies in Communication and Journalism, University of Mysore, Manasagangothri, Mysore-570006, Karnataka, India. Abstract The Lumiere brothers came over to India in 1896 and exhibited some films for the benefit of publics. D.G.Phalke is known as the founding father of Indian film industry. The first Indian talkie film Alam Ara was produced in 1931 by Ardeshir Irani. In the age of mooki films, about 1000 films were made in India. A new age of talkie films began in India in 1929. The decade of 1940s witnessed remarkable growth of Indian film industry. The Indian films grew well statistically and qualitatively in the post-independence period. In the decade of 1960s, Bollywood and regional films grew very well in the country because of the technological advancements and creative ventures. In the decade of 1970s, new experiments were conducted by the progressive film makers in India. In the decade of 1980s, the commercial films were produced in large number in order to entertain the masses and generate income. Television also gave a tough challenge to the film industry in the decade of 1990s. -

Spectacle Spaces: Production of Caste in Recent Tamil Films

South Asian Popular Culture ISSN: 1474-6689 (Print) 1474-6697 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rsap20 Spectacle spaces: Production of caste in recent Tamil films Dickens Leonard To cite this article: Dickens Leonard (2015) Spectacle spaces: Production of caste in recent Tamil films, South Asian Popular Culture, 13:2, 155-173, DOI: 10.1080/14746689.2015.1088499 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14746689.2015.1088499 Published online: 23 Oct 2015. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rsap20 Download by: [University of Hyderabad] Date: 25 October 2015, At: 01:16 South Asian Popular Culture, 2015 Vol. 13, No. 2, 155–173, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14746689.2015.1088499 Spectacle spaces: Production of caste in recent Tamil films Dickens Leonard* Centre for Comparative Literature, University of Hyderabad, Hyderabad, India This paper analyses contemporary, popular Tamil films set in Madurai with respect to space and caste. These films actualize region as a cinematic imaginary through its authenticity markers – caste/ist practices explicitly, which earlier films constructed as a ‘trope’. The paper uses the concept of Heterotopias to analyse the recurrence of spectacle spaces in the construction of Madurai, and the production of caste in contemporary films. In this pursuit, it interrogates the implications of such spatial discourses. Spectacle spaces: Production of caste in recent Tamil films To foreground the study of caste in Tamil films and to link it with the rise of ‘caste- gestapo’ networks that execute honour killings and murders as a reaction to ‘inter-caste love dramas’ in Tamil Nadu,1 let me narrate a political incident that occurred in Tamil Nadu – that of the formation of a socio-political movement against Dalit assertion in December 2012. -

US Eyelights August

Number : 27 August 2021 Sankara Nethralaya USA Sankara Nethralaya USA 9710, Traville Gateway Drive No.392, Rockville, MD 20850 e-mail : [email protected] Sankara Nethralaya’s new centre at R. A. Puram August 2021 2 Sankara Nethralaya Fundraiser – A Grand Success Sankara Nethralaya (SN) is a non-profit charity organization providing ophthalmic (eye) care throughout India. For the last four decades, SN has treated millions of patients. Sankara Nethralaya USA (SN USA) was formed in the USA thirty years ago so NRIs could contribute to help mission of SN. SN USA, based in the USA, has received the highest rating of four stars by Charity Navigator for maintaining financial accountability and fiscal transparency for funds donated by donors and how they are utilized towards the stated cause. Every year, Sankara Nethralaya USA organizes Indian classical dance and music programs in various cities to raise awareness and raise funds. Because of the pandemic, all programs have been conducted virtually. As part of our mid-year campaign, Kalaratna Vidwan Flute Nagaraju Talluri gave a devotional flute music concert on July 25th, 2021. He performed the following songs: Ÿ Maha Ganapateem - Lord Ganesh Ÿ Adivo Alladivo - Annamayya Ÿ Janani Janani - Tamil song by Ilayaraja Ÿ Shyam Teri Bansi- Hindi- Lata Mangeshkar Ÿ Bhagyada Laxmi Baaramma- Kannada Ÿ Tandanaanaa Hare - Annamayya Ÿ Payoji Maine Raam Ratan Dhan Payo - Hindi - Meera bhajan Ÿ Harivaraasanam – a popular Malayalam song for Ayyappa Swami first sung by Shri K. J. Yesudas Ÿ Shankara Nada Sharirapara - SPB - Sankarabharanam Ÿ Sathyam Shivam Sundaram - Hindi - Lata Mangeshkar 3 August 2021 Sankara Nethralaya executive committee members - President Emeritus S V Acharya, President Bala Reddy Indurti, Vice President Moorthy Rekapalli, Secretary Srinivas Ganagoni, Treasurer Banumati Ramkrishnan, Joint Secretary Sowmiya Narayanan, Joint Treasurer Raja Krishnamurti, and Past President Leela Krishnamurthy appealed the audience through TV channels to support the cause and help indigent blind patients in India. -

Top 10 Male Indian Singers

Top 10 Male Indian Singers 001asd Don't agree with the list? Vote for an existing item you think should be ranked higher or if you are a logged in,add a new item for others to vote on or create your own version of this list. Share on facebookShare on twitterShare on emailShare on printShare on gmailShare on stumbleupon4 The Top Ten TheTopTens List Your List 1Sonu Nigam +40Son should be at number 1 +30I feels that I have goten all types of happiness when I listen the songs of sonu nigam. He is my idol and sometimes I think that he is second rafi thumbs upthumbs down +13Die-heart fan... He's the best! Love you Sonu, your an idol. thumbs upthumbs down More comments about Sonu Nigam 2Mohamed Rafi +30Rafi the greatest singer in the whole wide world without doubt. People in the west have seen many T.V. adverts with M. Rafi songs and that is incediable and mind blowing. +21He is the greatest singer ever born in the world. He had a unique voice quality, If God once again tries to create voice like Rafi he wont be able to recreate it because God creates unique things only once and that is Rafi sahab's voice. thumbs upthumbs down +17Rafi is the best, legend of legends can sing any type of song with east, he can surf from high to low with ease. Equally melodious voice, well balanced with right base and high range. His diction is fantastic, you may feel every word. Incomparable. More comments about Mohamed Rafi 3Kumar Sanu +14He holds a Guinness World Record for recording 28 songs in a single day Awards *. -

Devdas by Sanjay Leela Bhansali

© 2018 JETIR July 2018, Volume 5, Issue 7 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) Adaptation of the novel ‘Devdas’ in the Film ‘Devdas by Sanjay Leela Bhansali In Bollywood, numerous adaptations have been produced using the great books. Devdas is a standout amongst the most well known and best example of those movies. The novel Devdas was written in Bengali in 1917 by Sarat Chandra Chatterjee, who is usually acclaimed as an 'Incredible Storyteller'. The account of Devdas has been adapted by P. C. Barua who directed three variants of Devdas between 1935 to 1937, in Bengali, Hindi, and Assamese; different adaptations have been made in Tamil and Malayalam. In 1955, Bimal Roy also adapted the narrative of Devdas featuring Dilip Kumar as a male protagonist and became a huge success in the history of Bollywood film. Again in 2002, a standout amongst the most popular director of India of the present day, 'Sanjay Leela Bhanshali', who is well known for his established flicks; Monsoon, Guzaarish, Hum Dil De Chuke Sanam, Goliyon Ki Raaslila Ram – Leela, Bajirao Mastaani and the most controversial film of 2018 Padmawat, has also adapted the story of this classical novel ‘Devdas’. Devdas by Sarat Chandra Chaterjee is one of the classics of Indian Literature, subject to many film adaptations in Indian Cinema. Sarat Chandra Chatterjee was one of the leading literary deities of Bengal, he published several books earlier Nishkriti, Charitraheen, Parineeta, and Srikanta, but his most famous novel is Devdas. Devdas is a tragic story of a man called Devdas who adored however never got his beloved. -

The Sixth String of Vilayat Khan

Published by Context, an imprint of Westland Publications Private Limited in 2018 61, 2nd Floor, Silverline Building, Alapakkam Main Road, Maduravoyal, Chennai 600095 Westland, the Westland logo, Context and the Context logo are the trademarks of Westland Publications Private Limited, or its affiliates. Copyright © Namita Devidayal, 2018 Interior photographs courtesy the Khan family albums unless otherwise acknowledged ISBN: 9789387578906 The views and opinions expressed in this work are the author’s own and the facts are as reported by her, and the publisher is in no way liable for the same. All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without express written permission of the publisher. Dedicated to all music lovers Contents MAP The Players CHAPTER ZERO Who Is This Vilayat Khan? CHAPTER ONE The Early Years CHAPTER TWO The Making of a Musician CHAPTER THREE The Frenemy CHAPTER FOUR A Rock Star Is Born CHAPTER FIVE The Music CHAPTER SIX Portrait of a Young Musician CHAPTER SEVEN Life in the Hills CHAPTER EIGHT The Foreign Circuit CHAPTER NINE Small Loves, Big Loves CHAPTER TEN Roses in Dehradun CHAPTER ELEVEN Bhairavi in America CHAPTER TWELVE Portrait of an Older Musician CHAPTER THIRTEEN Princeton Walk CHAPTER FOURTEEN Fading Out CHAPTER FIFTEEN Unstruck Sound Gratitude The Players This family chart is not complete. It includes only those who feature in the book. CHAPTER ZERO Who Is This Vilayat Khan? 1952, Delhi. It had been five years since Independence and India was still in the mood for celebration. -

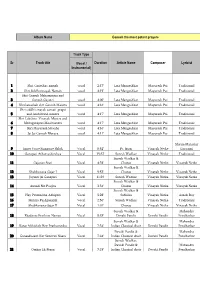

Album Name Ganesh the Most Potent Prayers Sr Track Title Track Type

Album Name Ganesh the most potent prayers Track Type Sr Track title (Vocal / Duration Artiste Name Composer Lyricist Instrumental) 1 Shri Ganeshay namah vocal 2:17' Lata Mangeshkar Mayuresh Pai Traditional 2 Shri Siddhivinayak Naman vocal 4:15' Lata Mangeshkar Mayuresh Pai Traditional Shri Ganesh Mahamantra and 3 Ganesh Gayatri vocal 4:00' Lata Mangeshkar Mayuresh Pai Traditional 4 Kleshanashak shri Ganesh Mantra vocal 4:16' Lata Mangeshkar Mayuresh Pai Traditional Shri siddhivinayak santati-prapti 5 and Aashirvaad mantra vocal 4:17' Lata Mangeshkar Mayuresh Pai Traditional Shri Lakshmi-Vinayak Mantra and 6 Mahaganapati Moolmantra vocal 4:17' Lata Mangeshkar Mayuresh Pai Traditional 7 Shri Mayuresh Stavaha vocal 4:16' Lata Mangeshkar Mayuresh Pai Traditional 8 Jai Jai Ganesh Moraya vocal 4:11' Lata Mangeshkar Mayuresh Pai Traditional Shyam Manohar 9 Inner Voice Signature Shlok Vocal 0:52' Pt. Jasraj Vinayak Netke Goswami 10 Ganapati Atharvashirshya Vocal 15:37' Suresh Wadkar Vinayak Netke Traditional Suresh Wadkar & 11 Gajanan Stuti Vocal 4:35' Chorus Vinayak Netke Vinayak Netke Suresh Wadkar & 12 Shubhanana Gajar I Vocal 5:53' Chorus Vinayak Netke Vinayak Netke 13 Jayanti jai Ganapati Vocal 11:39' Suresh Wadkar Vinayak Netke Vinayak Netke Suresh Wadkar & 14 Anaadi Nit Poojita Vocal 3:34' Chorus Vinayak Netke Vinayak Netke Suresh Wadkar & 15 Hey Prarambha Adhipati Vocal 5:28' Sabhiha Vinayak Netke Ashok Roy 16 Mantra Pushpaanjali Vocal 2:56' Suresh Wadkar Vinayak Netke Traditional 17 Shubhanana Gajar II Vocal 1:01' Chorus Vinayak Netke -

Contact Details of Zonal-Directorates- Regional Response Team

CONTACT DETAILS OF ZONAL/ DIRECTORATES/ REGIONAL RESPONSE TEAM AS ON 24.05.2021 S.NO ZONE COMMISSIONERATE / NAME OF OFFICER DESIGNATION CONTACT DETAILS DIRECTORATE NATIONAL RESPONSE TEAM (NRT) FOR COORDINATION AND MANAGEMENT AT CENTRAL LEVEL CBIC Ms. Sungita Sharma Member 9923481401 (Admin & Vig.) DGHRD Ms. Neeta Lall Butalia DG, HRD 9818896882 DGHRD Ms. Sucheta Sreejesh ADG, (I&W), 9811389065 DGHRD GST Ahmedabad Zone CGST Ahmedabad Zone Zonal Response Team Sunil Kumar Singh Pr. Commissioner 9725011100 Commissionerate of Central GST, 8866012461 M. L. Meena Additional Commissioner Ahmedabad North Commissionerate., CGST, 9930527884 B. P. Singh Additional Commissioner Ahmedabad South Commissionerate. CGST, 9624862544 Ravindra kumar Tiwari Joint Commissioner Bhavnagar Commissionerate, CGST, 9408495132 Nitina Nagori Joint Commissioner Gandhinagar Commissionerate, CGST, Kutch Group 1: Care Giver Group (Gandhidham) 997186904 Commissionerate, CGST, Rajkot Murali Rao R. J DC (Group Leader-I) Commissionerate, CGST (Audit), 9898296805 Ahmedabad D. P. Parmar AC (Group Leader-II) Commissionerate, (Appeal) CGST, 9825324567 Mahesh Chowdhary Superintendent Rajkot Commissionerate CGST (Appeal), 9427705862 Ajit R. Singh Superintendent Ahmedabad Commissionerate, CGST (Audit), 9879564321 Jignesh Soyantar Superintendent Rajkot B S Lakhani Superintendent 9998112363 Deepesh Superintendent 8238699316 Tarun Ayani Superintendent 8160233892 Prabhat Ayani Inspector (Supdt in-situ) 8306384308 Shyam Sundar Chaudhary Inspector (Supdt in-situ) 9377211217 Nagesh Kumar