Spectacle Spaces: Production of Caste in Recent Tamil Films

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Camp Sitting at Chennai, Tamil Nadu Full Commission V

NATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS COMMISSION (LAW DIVISION – FULL COMMISSION BRANCH) CAMP SITTING AT CHENNAI, TAMIL NADU FULL COMMISSION CAUSE LIST CORAM: Mr. Justice H.L. Dattu - Chairperson Mr. Justice P.C. Pant - Member Mrs. Jyotika Kalra - Member Dr. D.M. Mulay - Member Friday, 13th September, 2019 at 10.00 A.M. Venue: Anna Centenary Library, Gandhi Mandapam Road, Surya Nagar, Kotturpuram, Chennai, Tamil Nadu S. Case No. Complainant/In Name of authority No timation received from 1. 512/22/0/2019 Suo-motu Principal Secretary, Suo-motu cognizance of a news item Labour and published in “Business Line” dated Employment (M2) 21.02.2019 highling the plight of thousands Deptt., Govt of Tamil of garmet factory workers in Tamil Nadu. Nadu 2. 896/22/37/2010 Shri Devika Chief Secretary Illegal arrest of five members of Fact Finding Prasad Director General of Team by Veeravanallur Police, Tiruneveli, Shri Henri Police Tamil Nadu Tiphagne 3. 590/22/42/2019 Shri A.P. Disitrict Collector, Complaint regarding families living without Gowdhamasidha Villupuram, Tamil Nadu shelter in Villupuram District, Tamil Nadu rthan 4. 554/22/12/2017 Shri T.D. Commissioner, Avadi Inaction by District Administration in regard Ramalingam Municipality to the complaint of stagnation of drainage District Collector and rain water in area in Awadi Municipality Tiruvallur 5. 807/22/13/2019 Shri Radhakanta The District Magistrate Complaint regarding gang-rape of a 11 year Tripathy Chennai old deaf girl in Chennai on 17.07.2018 for The Commissioner of which seventeen men were charged. Police,Chennai 6. 308/22/39/2019 Suo-motu Additional Chief Suo-motu cognizance of a news report carried Secretary Home out by “News 18” regarding sexual abuse of 15 (Pol.XII) Department, minor girls who were rescused from a Home in Tamil Nadu Tiruvannamalai, Tamil Nadu. -

Addendum to Notice of 2Nd/2016-17 Extra Ordinary General

The Indian Performing Right Society Limited CIN: U92140MH1969GAP014359 Regd. Office: 208, Golden Chambers, New Andheri Link Road, Andheri (West), Mumbai– 400053 Tel: 2673 3748/49/50/6616 Fax: 26736658. Email:[email protected] Website: www.iprs.org ADDENDUM TO THE NOTICE Addendum is hereby given to the Original Notice of the 2nd/2016-17 Extra-Ordinary General Meeting (‘EOGM’) of the Members of The Indian Performing Right Society Limited which will be held at Shri Bhaidas Maganlal Sabhagriha, U-1, J.V.P.D. Scheme, Vile Parle (West), Mumbai – 400 056 on Friday, the 31st day of March, 2017 at 10:30 A.M. to transact the following business: FOLLOWING RESOLUTIONS VIDE ITEM NOS. 6 TO 11 BEING RESOLUTIONS FOR APPOINTMENT OF NOMINEE DIRECTORS OF AUTHOR/COMPOSER MEMBERS, ARE FOR VOTING BY AUTHOR/ COMPOSER MEMBERS ONLY IN ACCORDANCE WITH ARTICLE 24(i) OF THE ARTICLES OF ASSOCIATION OF THE COMPANY: 6. To consider and if thought fit, to pass, with or without modification(s), the following resolution as an Ordinary Resolution: “RESOLVED THAT pursuant to the provisions of Sections 152 and 160 and other applicable provisions, if any, of the Companies Act, 2013 read with the Companies (Appointment and Qualification of Directors) Rules, 2014 (including any statutory modification(s) or re-enactment thereof for the time being in force) and in accordance with Article 24 of the Articles of Association of the Company, Mr. Javed Jannisar Akhtar, who fulfills the criteria for appointment of Director in accordance with Article 20(b) of the Articles of Association of the Company and in respect of whom the Company has received a notice in writing from him under Section 160 of the Companies Act, 2013 along with necessary security deposit amount, proposing his candidature for the office of Author/Composer Director-Region-West, be and is hereby appointed as a Director of the Company who shall be liable to retire by rotation. -

South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal , Free-Standing Articles Madurai Formula Films: Caste Pride and Politics in Tamil Cinema 2

Edinburgh Research Explorer Madurai Formula Films Citation for published version: Damodaran, K & Gorringe, H 2017, 'Madurai Formula Films', South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal (SAMAJ), pp. 1-30. <https://samaj.revues.org/4359> Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Published In: South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal (SAMAJ) General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 28. Sep. 2021 South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal Free-Standing Articles Madurai Formula Films: Caste Pride and Politics in Tamil Cinema Karthikeyan Damodaran and Hugo Gorringe Publisher Association pour la recherche sur l'Asie du Sud (ARAS) Electronic version URL: http://samaj.revues.org/4359 ISSN: 1960-6060 Electronic reference Karthikeyan Damodaran and Hugo Gorringe, « Madurai Formula Films: Caste Pride and Politics in Tamil Cinema », South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal [Online], Free-Standing Articles, Online since 22 June 2017, connection on 22 June 2017. URL : http://samaj.revues.org/4359 This text was automatically generated on 22 June 2017. -

Karan Johar Shahrukh Khan Choti Bahu R. Madhavan Priyanka

THIS MONTH ON Vol 1, Issue 1, August 2011 Karan Johar Director of the Month Shahrukh Khan Actor of the Month Priyanka Chopra Actress of the Month Choti Bahu Serial of the Month R. Madhavan Host of the Month Movie of the Month HAUNTED 3D + What’s hot Kids section Gadget Review Music Masti VAS (Value Added Services) THIS MONTH ON CONTENTS Publisher and Editor-in-Chief: Anurag Batra Editorial Director: Amit Agnihotri Editor: Vinod Behl Directors: Nawal Ahuja, Ritesh Vohra, Kapil Mohan Dhingra Advisory Board Anuj Puri, (Chairman & Country Head, Jones Lang LaSalle India) Laxmi Goel, (Director, Zee News & Chairman, Suncity Projects) Ajoy Kapoor (CEO, Saffron Real Estate Management) Dr P.S. Rana, Ex-C( MD, HUDCO) Col. Prithvi Nath, (EVP, NAREDCO & Sr Advisor, DLF Group) Praveen Nigam, (CEO, Amplus Consulting) Dr. Amit Kapoor, (Professor in Strategy and nd I ustrial Economics, MDI, Gurgoan) Editorial Editorial Coordinating Editor : Vishal Duggal Assistant Editor : Swarnendu Biswas da con parunt, ommod earum sit eaqui ipsunt abo. Am et dias molup- Principal Correspondent : Vishnu Rageev R tur mo beressit rerum simpore mporit explique reribusam quidella Senior Correspondent : Priyanka Kapoor U Correspondents : Sujeet Kumar Jha, Rahul Verma cus, ommossi dicte eatur? Em ra quid ut qui tem. Saecest, qui sandiorero tem ipic tem que Design Art Director : Jasper Levi nonseque apeleni entustiori que consequ atiumqui re cus ulpa dolla Sr. Graphic Designers : Sunil Kumar preius mintia sint dicimi, que corumquia volorerum eatiature ius iniam res Photographe r : Suresh Gola cusapeles nieniste veristo dolore lis utemquidi ra quidell uptatiore seque Advertisment & Sales nesseditiusa volupta speris verunt volene ni ame necupta consequas incta Kapil Mohan Dhingra, [email protected], Ph: 98110 20077 sumque et quam, vellab ist, sequiam, amusapicia quiandition reprecus pos 3 Priya Patra, [email protected], Ph: 99997 68737, New Delhi Sneha Walke, [email protected], Ph: 98455 41143, Bangalore ute et, coressequod millaut eaque dis ariatquis as eariam fuga. -

Tamil Flac Songs Free Download Tamil Flac Songs Free Download

tamil flac songs free download Tamil flac songs free download. Get notified on all the latest Music, Movies and TV Shows. With a unique loyalty program, the Hungama rewards you for predefined action on our platform. Accumulated coins can be redeemed to, Hungama subscriptions. You can also login to Hungama Apps(Music & Movies) with your Hungama web credentials & redeem coins to download MP3/MP4 tracks. You need to be a registered user to enjoy the benefits of Rewards Program. You are not authorised arena user. Please subscribe to Arena to play this content. [Hi-Res Audio] 30+ Free HD Music Download Sites (2021) ► Read the definitive guide to hi-res audio (HD music, HRA): Where can you download free high-resolution files (24-bit FLAC, 384 kHz/ 32 bit, DSD, DXD, MQA, Multichannel)? Where to buy it? Where are hi-res audio streamings? See our top 10 and long hi-res download site list. ► What is high definition audio capability or it’s a gimmick? What is after hi-res? What's the highest sound quality? Discover greater details of high- definition musical formats, that, maybe, never heard before. The explanation is written by Yuri Korzunov, audio software developer with 20+ years of experience in signal processing. Keep reading. Table of content (click to show). Our Top 10 Hi-Res Audio Music Websites for Free Downloads Where can I download Hi Res music for free and paid music sites? High- resolution music free and paid download sites Big detailed list of free and paid download sites Download music free online resources (additional) Download music free online resources (additional) Download music and audio resources High resolution and audiophile streaming Why does Hi Res audio need? Digital recording issues Digital Signal Processing What is after hi-res sound? How many GB is 1000 songs? Myth #1. -

Cinema of the Social: Stars, Fans and the Standardization of Genre in Tamil Cinema

Western University Scholarship@Western Digitized Theses Digitized Special Collections 2011 CINEMA OF THE SOCIAL: STARS, FANS AND THE STANDARDIZATION OF GENRE IN TAMIL CINEMA Ganga Rudraiah Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/digitizedtheses Recommended Citation Rudraiah, Ganga, "CINEMA OF THE SOCIAL: STARS, FANS AND THE STANDARDIZATION OF GENRE IN TAMIL CINEMA" (2011). Digitized Theses. 3315. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/digitizedtheses/3315 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Digitized Special Collections at Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Digitized Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CINEMA OF THE SOCIAL: STARS, FANS AND THE STANDARDIZATION OF GENRE IN TAMIL CINEMA r , ' (Spine title: CINEMA OF THE SOCIAL) (Thesis Format: Monograph) by : Ganga Rudraiah Graduate Program in Film Studies A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Ganga Rudraiah 2011 THE UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN ONTARIO SCHOOL OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES CERTIFICATE OF EXAMINATION r Supervisor Examiners Dr. Christopher E. Glttings Dr. James Prakash Younger Supervisory Committee Dr. Constanza Burucúa Dr. Chris Holmlund The thesis by Ganga Rudraiah entitled: Cinema of the Social: Stars, Fans and the Standardization of Genre in Tamil Cinema is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Date Chair of the Thesis Examination Board Abstract The star machinery of Tamil cinema presents itself as a nearly unfathomable system that produces stars and politicians out of actors and fans out of audiences in an organized fashion. -

GEM SAP CODE GEM NAME Department PEOPLE MANAGER

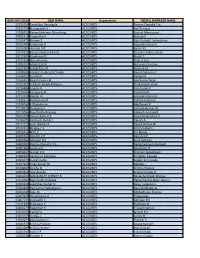

GEM SAP CODE GEM NAME Department PEOPLE MANAGER NAME 23191950 Dorababu Derangula ACCOUNTS Poorna Chandra Trp 23157794 Kirangowda S ACCOUNTS Anil Kumara 23188751 Devendrakumar Mundaragi ACCOUNTS Govind Meesiyavar 24005319 Sangeetha P ACCOUNTS Kishore R 23205471 Naveen S ACCOUNTS Raju Polisetti Velanganee 23163149 Sivakumar R ACCOUNTS Gopalakrishnan V 23141084 Arunlal G R ACCOUNTS Jobish P J 23147333 Ramasubbaiah Pamidi ACCOUNTS Chandra Sekhar Avula 23117944 Sivakumar D ACCOUNTS Beniel T 23171294 Jibin Johnson ACCOUNTS Shiju A Jose 23183337 Ashok Sajjala ACCOUNTS Narendra Gurram 23157400 Esakki Raja M ACCOUNTS Ramesh M 23108369 Venkata Subbaiah Chukka ACCOUNTS Murali Sakamuri 23166055 Suresh N ACCOUNTS Vadivel A 23164453 Rajesh Kumar M ACCOUNTS Anil Kumar Nese 23142301 Subhash Reddy Polimera ACCOUNTS Shaikshavali Shaik 23194888 Lingam R ACCOUNTS Sasi Kumar K 23174042 Kanagaraj M ACCOUNTS Sampath M 23193190 Rakesh M ACCOUNTS Gopalakrishnan R 23140155 Kumaresan M ACCOUNTS Sathish Kumar G 23148769 K Dhinakaran ACCOUNTS Madhavan R 23118535 Kanagaraj S ACCOUNTS Saravanakumar M 23114764 Nagi Reddy Koppala ACCOUNTS Srikanth Gorlapalli 23165228 Dinesh Babu K.K ACCOUNTS Siva Subramanian P 23144676 Santhosh Kumar J ACCOUNTS Dinesh A 23122519 Selin Mehala P ACCOUNTS Rajesh Kumar M 23122212 Bhagya C S ACCOUNTS Girish Kulkarni 23159112 Binci C ACCOUNTS K P Bijuraj 23105734 Vineeth V P ACCOUNTS Rajesh A P 24003561 Abhilash B S ACCOUNTS Sunil Sathyan 23065051 Poorna Chandra Trp ACCOUNTS Ramanjaneyulu Bylupati 23207162 Saranraj K ACCOUNTS Rajendran R 24003617 -

RANK App No. Name Gender Community Marks 1 358876

DCE COURSEWISE REPORT, COURSE CODE-APOT1-2021-08-18 DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE FINAL RANK LIST (TAMIL MEDIUM) RANK APPLICATION NAME GENDER COMMUNITY STREAM CUT-OFF MARKS REMARKS NO 1 309641 SACHIN KUMAR S Male MBC AND DNC HSC Academic 379.33 2 499988 AMRUTA K S Female BC HSC Academic 375.00 3 410135 MOHAN P Male MBC (V) HSC Academic 373.36 4 249284 KARUPPAIYA V Male BC HSC Academic 369.36 5 227689 PRAVINKUMAR K Male SC HSC Academic 369.00 6 289607 K.GOMATHI Female SCA HSC Academic 368.28 7 247035 L.MONIKA SABARI Female BC HSC Academic 368.24 8 421814 ARUNIKA K Female SC HSC Academic 368.00 9 359623 MANOJ M Male MBC AND DNC HSC Academic 367.97 10 425641 TAMIZHARASI.C Female SCA HSC Academic 364.04 11 222591 V.MUHIL DHARAN Male BC HSC Vocational 363.92 12 331734 AARTHI M Female BC HSC Academic 362.66 13 435155 ARULKUMAR S Male BC HSC Academic 362.25 14 248114 DHANAPRIYA P Female SC HSC Academic 362.00 15 276520 Srinath G Male SC HSC Academic 360.48 16 287526 MANIKANDAN.R Male OC HSC Academic 360.00 17 335986 KABIL M Male SC HSC Academic 359.57 18 386587 BETHANA SAMY P Male BC HSC Academic 359.36 19 250276 MADHUMITHA B Female SC HSC Academic 358.97 20 276942 DEEPAKRAHUL Male SCA HSC Academic 358.89 21 211707 A.NATHIYA Female BC HSC Academic 358.83 22 323536 M. MOUSMI Female SC HSC Academic 358.15 23 477006 NATHIYA S Female MBC (V) HSC Academic 357.87 24 364895 S. -

Magazine1-4 Final.Qxd (Page 3)

SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 1, 2019 (PAGE 4) MOVIE-REVIEW BOLLYWOOD-BUZZ Saaho suffers from a weak script “I opened up as an actor in Raabta” SAAHO is the story of a mysterious man on a mission. The foreign city of Vishwank and Ashok, Devraj threatening his father Prithviraj and of After Luka Chuppi, Kriti Sanon of Waaji is ruled by gangsters and criminals and the biggest of them is Roy course, the interval point. In the second half, he does very well in a brief once again plays the role of a (Jackie Shroff). He cleverly manages to get the approval of an Indian min- part of the climax where three scenes are running parallel - one of Ashok, ister, Ramaswamy (Tanikella Bharani) for a hydro project in India. He then one of Amrutha and one of Kalki. If he had wisely directed the rest of the reporter in her upcoming film reaches Mumbai and this is where he's killed in a road accident. His son film, SAAHO would have been on another level. Arjun Patiala, which stars Vishwank (Arun Vijay) then takes over, which angers Devraj (Chunky Pan- SAAHO has an average beginning. Too much information is laid out and Diljit Dosanjh in the lead role. day) as he wants to sit on Roy's throne. Meanwhile the Mumbai crime it takes a while to process it all. The film gets a bit better with Ashok's entry. branch is investigating the death of Roy and other related crimes. The case The investigation carried out by Ashok and his team is quite engaging. -

Results Cafoundation Cacpt

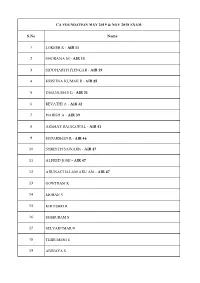

CA FOUNDATION MAY 2019 & NOV 2018 EXAM S.No Name 1 LOKESH K - AIR 11 2 SHOBANA M - AIR 15 3 SIDDHARTH IYENGAR - AIR 19 4 KRISHNA KUMAR R - AIR 25 5 DHANUSH S G - AIR 31 6 REVATHI A - AIR 32 7 HARISH A - AIR 39 8 AKSHAY RAJAGOPAL - AIR 41 9 SUDARSHAN R - AIR 46 10 SHRESTH SAWARN - AIR 47 11 ALFRED JOSE - AIR 47 12 ARUNACHALAM ARU AM - AIR 47 13 GOWTHAM K 14 MOHAN V 15 KIRTISHRI R 16 SUBBURAM S 17 SELVAKUMAR N 18 THIRUMENI E 19 ABINAYA S 20 YOKESH R 21 SANTHOSSH S 22 LOGESH S 23 SETHURAMAN S 24 SAJEETHAMBIGAI 25 JAYSUHITH TK 26 ARAVIND S 27 DHARAN KUMAR S 28 SANTHOSH P 29 SUGANTHI N 30 AHAMED BASHA T 31 MOHAMED NIYAS J 32 MOHAMMED SOHAILATHAR 33 AJAY KUMAR M 34 ASHWIN P 35 AJAY M 36 BALAJI M 37 CHANDRASEKAR V 38 AMRUDHA VARSHINI T S 39 GANESH V 40 VIVEGA V 41 PRAGATHI R 42 SURENDHER KUMAR S 43 SARAVANAN V 44 GOWTHAM G 45 SRIVATSAN A 46 NANDHINI DEVI 47 KARTHIKEYAN M 48 YAMINI V S 49 AJITH KUMAR M 50 SARAN PRASATH 51 ABINESH R 52 DESIKA A 53 MONIKA M 54 AADHITHIYA P 55 ABDULLAH TAHA 56 SANDESH A 57 BOOLIBHARATH R 58 SELVAMANI S 59 SUVEDHA R 60 HAJIRA SULTHANA D 61 PADMAVATHY S 62 SINGARAVELAN N 63 MANIKANDAN V 64 CAROLIN ROSE C 65 AAKASH A 66 SANKARA NARAYANAN V 67 DHEVIYA S 68 RAHITH R 69 DINESH V 70 GAYATHRE J 71 SIVA KUMAR S 72 SHALINI SIVAKUMAR 73 KARTHICK B 74 ISHWARYA G 75 SRIKANTH V 76 MAHALAKSHMI C 77 AMRITHA PRIYADHARSHINI 78 ABIRAMI V 79 SHARMILA C K 80 SUJITHA R 81 VINAY D 82 GURUPRASATH 83 VIJAY MANI K 84 BASKARAN S 85 OVIYA N 86 LEON NOEL M 87 AFFAN JAWEED GUNDU 88 PRASANNA RAMANAA MV 89 DINESH M 90 MOHAMED ANSAR 91 SREEKANTH -

Police Matters: the Everyday State and Caste Politics in South India, 1900�1975 � by Radha Kumar

PolICe atter P olice M a tte rs T he v eryday tate and aste Politics in South India, 1900–1975 • R a dha Kumar Cornell unIerIt Pre IthaCa an lonon Copyright 2021 by Cornell University The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License: https:creativecommons.orglicensesby-nc-nd4.0. To use this book, or parts of this book, in any way not covered by the license, please contact Cornell University Press, Sage House, 512 East State Street, Ithaca, New ork 14850. Visit our website at cornellpress.cornell.edu. First published 2021 by Cornell University Press Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Kumar, Radha, 1981 author. Title: Police matters: the everyday state and caste politics in south India, 19001975 by Radha Kumar. Description: Ithaca New ork: Cornell University Press, 2021 Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2021005664 (print) LCCN 2021005665 (ebook) ISBN 9781501761065 (paperback) ISBN 9781501760860 (pdf) ISBN 9781501760877 (epub) Subjects: LCSH: Police—India—Tamil Nadu—History—20th century. Law enforcement—India—Tamil Nadu—History—20th century. Caste— Political aspects—India—Tamil Nadu—History. Police-community relations—India—Tamil Nadu—History—20th century. Caste-based discrimination—India—Tamil Nadu—History—20th century. Classification: LCC HV8249.T3 K86 2021 (print) LCC HV8249.T3 (ebook) DDC 363.20954820904—dc23 LC record available at https:lccn.loc.gov2021005664 LC ebook record available at https:lccn.loc.gov2021005665 Cover image: The Car en Route, Srivilliputtur, c. 1935. The British Library Board, Carleston Collection: Album of Snapshot Views in South India, Photo 6281 (40). -

ANNUAL REPORT June 2016 – May 2017

MOTHER TERESA WOMEN’S UNIVERSITY KODAIKANAL ANNUAL REPORT June 2016 – May 2017 Edited by : Dr.A.Muthu Meena Losini Assistant Professor Department of English Mother Teresa Women‘s University Kodaikanal Technical Assistance by : Mrs.T.Amutha Technical Assistant Department of Physics Mother Teresa Women‘s University Kodaikanal MOTHER TERESA WOMEN‟S UNIVERSITY (Accredited with „B‟ Grade by NACC) KODAIKANAL – 624 101 This is the Annual Report for the period June 2016 – May 2017 of the Mother Teresa Women‘s University, Kodaikanal. The report gives all Academic, Administrative and other relevant details pertaining to the period June 2016 – May 2017. I take this occasion to thank all the members of the Executive Council, Academic Committee and Finance Committee for all their participation and contribution to the growth and development of the University and look forward to their continued advice and guidance. Dr. G. Valli VICE-CHANCELLOR INTRODUCTION The Executive Council has great pleasure in presenting to the Academic Committee, the Annual report for the period June 2016- May 2017 as per the requirement of the section 26 of Chapter IV of Mother Teresa Women‘s University Act 1984. The report outlines the various activities which have paved for the growth and development of the University through the period June 2016 –May 2017 in the areas of Teaching, Research and Extension; it provides a detailed account of various Academic Achievements, Introduction of new Innovative Courses, Conduct of Seminar/ Workshop/ Conferences at Regional, National and International levels and its extension activities. OFFICERS AND AUTHORITIES OF THE UNIVERSITY CHANCELLOR - HIS EXCELLENCY HON‘BLE Banwarilal Purohit Governor of Tamil Nadu PRO – CHANCELLOR - HONOURABLE Thiru.