R208.81C Assault on an Officer and Simple Assault

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cops Or Robbers? How Georgia's Defense of Habitation Statute Applies to No-Knock Raids by Police Dimitri Epstein

Georgia State University Law Review Volume 26 Article 5 Issue 2 Winter 2009 March 2012 Cops or Robbers? How Georgia's Defense of Habitation Statute Applies to No-Knock Raids by Police Dimitri Epstein Follow this and additional works at: https://readingroom.law.gsu.edu/gsulr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Dimitri Epstein, Cops or Robbers? How Georgia's Defense of Habitation Statute Applies to No-Knock Raids by Police, 26 Ga. St. U. L. Rev. (2012). Available at: https://readingroom.law.gsu.edu/gsulr/vol26/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Publications at Reading Room. It has been accepted for inclusion in Georgia State University Law Review by an authorized editor of Reading Room. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Epstein: Cops or Robbers? How Georgia's Defense of Habitation Statute App COPS OR ROBBERS? HOW GEORGIA'S DEFENSE OF HABITATION STATUTE APPLIES TO NONO- KNOCK RAIDS BY POLICE Dimitri Epstein*Epstein * INTRODUCTION Late in the fall of 2006, the city of Atlanta exploded in outrage when Kathryn Johnston, a ninety-two-year old woman, died in a shoot-out with a police narcotics team.team.' 1 The police used a "no"no- knock" search warrant to break into Johnston's home unannounced.22 Unfortunately for everyone involved, Ms. Johnston kept an old revolver for self defense-not a bad strategy in a neighborhood with a thriving drug trade and where another elderly woman was recently raped.33 Probably thinking she was being robbed, Johnston managed to fire once before the police overwhelmed her with a "volley of thirty-nine" shots, five or six of which proved fatal.fata1.44 The raid and its aftermath appalled the nation, especially when a federal investigation exposed the lies and corruption leading to the incident. -

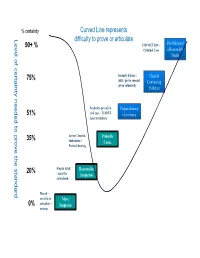

Level of Certainty Needed to Prove the Standard

% certainty Curved Line represents Level of certainty needed to prove the standard needed toprove of certainty Level difficulty to prove or articulate 90+ % CONVICTION – Proof Beyond Criminal Case a Reasonable Doubt 75% Insanity defense / Clear & alibi / prove consent Convincing given voluntarily Evidence Needed to prevail in Preponderance 51% civil case – LIABLE of evidence Asset Forfeiture 35% Arrest / Search / Probable Indictment / Cause Pretrial hearing 20% Stop & Frisk Reasonable – must be Suspicion articulated Hunch – not able to Mere 0% articulate / Suspicion no stop Mere Suspicion – This term is used by the courts to refer to a hunch or intuition. We all experience this in everyday life but it is NOT enough “legally” to act on. It does not mean than an officer cannot observe the activity or person further without making contact. Mere suspicion cannot be articulated using any reasonably accepted facts or experiences. An officer may always make a consensual contact with a citizen without any justification. The officer will however have not justification to stop or hold a person under this situation. One might say something like, “There is just something about him that I don’t trust”. “I can’t quit put my finger on what it is about her.” “He looks out of place.” Reasonable Suspicion – Stop, Frisk for Weapons, *(New) Search of vehicle incident to arrest under Arizona V. Gant. The landmark case for reasonable suspicion is Terry v. Ohio, 392 U.S. 1 (1968) This level of proof is the justification police officers use to stop a person under suspicious circumstances (e.g. a person peaking in a car window at 2:00am). -

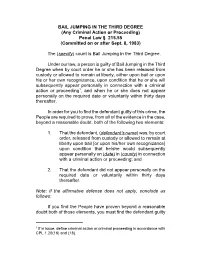

BAIL JUMPING in the THIRD DEGREE (Any Criminal Action Or Proceeding) Penal Law § 215.55 (Committed on Or After Sept

BAIL JUMPING IN THE THIRD DEGREE (Any Criminal Action or Proceeding) Penal Law § 215.55 (Committed on or after Sept. 8, 1983) The (specify) count is Bail Jumping in the Third Degree. Under our law, a person is guilty of Bail Jumping in the Third Degree when by court order he or she has been released from custody or allowed to remain at liberty, either upon bail or upon his or her own recognizance, upon condition that he or she will subsequently appear personally in connection with a criminal action or proceeding1, and when he or she does not appear personally on the required date or voluntarily within thirty days thereafter. In order for you to find the defendant guilty of this crime, the People are required to prove, from all of the evidence in the case, beyond a reasonable doubt, both of the following two elements: 1. That the defendant, (defendant’s name) was, by court order, released from custody or allowed to remain at liberty upon bail [or upon his/her own recognizance] upon condition that he/she would subsequently appear personally on (date) in (county) in connection with a criminal action or proceeding; and 2. That the defendant did not appear personally on the required date or voluntarily within thirty days thereafter. Note: If the affirmative defense does not apply, conclude as follows: If you find the People have proven beyond a reasonable doubt both of those elements, you must find the defendant guilty 1 If in issue, define criminal action or criminal proceeding in accordance with CPL 1.20(16) and (18). -

Conflict of the Criminal Statute of Limitations with Lesser Offenses at Trial

William & Mary Law Review Volume 37 (1995-1996) Issue 1 Article 10 October 1995 Conflict of the Criminal Statute of Limitations with Lesser Offenses at Trial Alan L. Adlestein Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr Part of the Criminal Law Commons Repository Citation Alan L. Adlestein, Conflict of the Criminal Statute of Limitations with Lesser Offenses at Trial, 37 Wm. & Mary L. Rev. 199 (1995), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr/vol37/iss1/10 Copyright c 1995 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr CONFLICT OF THE CRIMINAL STATUTE OF LIMITATIONS WITH LESSER OFFENSES AT TRIAL ALAN L. ADLESTEIN I. INTRODUCTION ............................... 200 II. THE CRIMINAL STATUTE OF LIMITATIONS AND LESSER OFFENSES-DEVELOPMENT OF THE CONFLICT ........ 206 A. Prelude: The Problem of JurisdictionalLabels ..... 206 B. The JurisdictionalLabel and the CriminalStatute of Limitations ................ 207 C. The JurisdictionalLabel and the Lesser Offense .... 209 D. Challenges to the Jurisdictional Label-In re Winship, Keeble v. United States, and United States v. Wild ..................... 211 E. Lesser Offenses and the Supreme Court's Capital Cases- Beck v. Alabama, Spaziano v. Florida, and Schad v. Arizona ........................... 217 1. Beck v. Alabama-LegislativePreclusion of Lesser Offenses ................................ 217 2. Spaziano v. Florida-Does the Due Process Clause Require Waivability? ....................... 222 3. Schad v. Arizona-The Single Non-Capital Option ....................... 228 F. The Conflict Illustrated in the Federal Circuits and the States ....................... 230 1. The Conflict in the Federal Circuits ........... 232 2. The Conflict in the States .................. 234 III. -

Reasonable Cause Exists When the Public Servant Has

ESCAPE IN THE SECOND DEGREE Penal Law § 205.10(2) (Escape from Custody by Defendant Arrested for, Charged with, or Convicted of Felony) (Committed on or after September 8, 1983) The (specify) count is Escape in the Second Degree. Under our law, a person is guilty of escape in the second degree when, having been arrested for [or charged with] [or convicted of] a class C [or class D] [or class E] felony, he or she escapes from custody. The following terms used in that definition have a special meaning: CUSTODY means restraint by a public servant pursuant to an authorized arrest or an order of a court.1 "Public Servant" means any public officer or employee of the state or of any political subdivision thereof or of any governmental instrumentality within the state, [or any person exercising the functions of any such public officer or employee].2 [Add where appropriate: An arrest is authorized when the public servant making the arrest has reasonable cause to believe that the person being arrested has committed a crime. 3 Reasonable cause does not require proof that the crime was in fact committed. Reasonable cause exists when the public servant has 1 Penal Law §205.00(2). 2 Penal Law §10.00(15). 3 This portion of the charge assumes an arrest for a crime only as authorized by the provisions of CPL 140.10(1)(b). If the arrest was authorized pursuant to some other subdivision of CPL 140.10 or other law, substitute the applicable provision of law. knowledge of facts and circumstances sufficient to support a reasonable belief that a crime has been or is being committed.4 ] ESCAPE means to get away, break away, get free or get clear, with the conscious purpose to evade custody.5 (Specify the felony for which the defendant was arrested, charged or convicted) is a class C [or class D] [or class E] felony. -

Burden of Proof and 4Th Amendment

Burden of Proof and 4 th Amendment Burden of Proof Standards • Reasonable suspicion • Probable cause • Reasonable doubt Burden of proof • In the United States we enjoy a ‘presumption of innocence’. What does this mean? • This means, essentially, that you are innocent until proven guilty. But how do we prove guilt? • Law enforcement officers must have some basis for stopping or detaining an individual. • In order for an officer to stop and detain someone they must meet a standard of proof Reasonable Suspicion • Lowest standard • A belief or suspicion that • Officers cannot deprive a citizen of liberty unless the officer can point to specific facts and circumstances and inferences therefrom that would amount to a reasonable suspicion Probable Cause • More likely than not or probably true. • Probable cause- a reasonable amount of suspicion, supported by circumstances sufficiently strong to justify a prudent and cautious person’s belief that certain facts are probably true. • In other terms this could be understood as more likely than not of 51% likely. • This is the standard required to arrest someone and obtain a warrant. Reasonable Doubt • Beyond a reasonable doubt- This means that the notion being presented by the prosecution must be proven to the extent that there could be no "reasonable doubt" in the mind of a “reasonable person” that the defendant is guilty. There can still be a doubt, but only to the extent that it would not affect a reasonable person's belief regarding whether or not the defendant is guilty. 4th Amendment • Search -

The Knock-And-Announce Rule and Police Arrests: Evaluating Alternative Deterrents to Exclusion for Rule Violations

\\jciprod01\productn\S\SAN\48-1\san103.txt unknown Seq: 1 3-JAN-14 14:43 The Knock-and-Announce Rule and Police Arrests: Evaluating Alternative Deterrents to Exclusion for Rule Violations By DR. CHRISTOPHER TOTTEN† & DR. SUTHAM COBKIT(CHEURPRAKOBKIT)‡ * Introduction IN ARRIVING AT THE DETERMINATION that the exclusionary rule no longer applies to knock-and-announce violations,1 the Supreme Court’s rationale in Hudson v. Michigan2 included the idea that factors other than exclusion exist to prevent police misconduct concerning the knock-and-announce rule.3 Particular examples of these alterna- tive factors relied upon by the Court are improved training, educa- tion, and internal discipline of police: † Dr. Christopher Totten is an Associate Professor of Criminal Justice (Law) in the Department of Sociology and Criminal Justice at Kennesaw State University. He has a JD and LLM from Georgetown University Law Center and an AB from Princeton University. He is the criminal law commentator for Volumes 46 through 50 of the Criminal Law Bulletin. ‡ Dr. Sutham Cobkit (Cheurprakobkit) is a Professor of Criminal Justice and Director of the Master of Science in Criminal Justice Program in the Department of Sociology and Criminal Justice at Kennesaw State University. He has a PhD in Criminal Justice from Sam Houston State University. * Both authors would like to thank the College of Humanities and Social Sciences at Kennesaw State University for providing a grant that partially funded the study described in this Article. 1. The knock-and-announce rule usually requires police to knock and to give notice to occupants of the officer’s presence and authority prior to entering a residence to make an arrest or conduct a search. -

Supreme Court of the United States

No. 18-556 IN THE Supreme Court of the United States STATE OF KANSAS, Petitioner, v. CHARLES GLOVER, Respondent. On Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Kansas BRIEF OF AMICUS CURIAE NATIONAL DISTRICT ATTORNEYS ASSOCIATION IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER Benjamin A. Geslison Scott A. Keller BAKER BOTTS L.L.P. Counsel of Record 910 Louisiana St. William J. Seidleck Houston, TX 77002 BAKER BOTTS L.L.P. (713) 229-1241 1299 Pennsylvania Ave. NW Washington, D.C. 20004 (202) 639-7700 [email protected] Counsel for Amicus Curiae National District Attorneys Association WILSON-EPES PRINTING CO., INC. – (202) 789-0096 – WASHINGTON, D.C. 20002 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Interest of Amicus Curiae .................................................. 1 Summary of Argument ........................................................ 2 Argument .............................................................................. 4 I. The Kansas Supreme Court Misapplied the Reasonable-Suspicion Standard and Imported Requirements from the Beyond-a-Reasonable- Doubt Standard ........................................................ 4 A. Officers May Have Reasonable Suspicion by Stacking Inferences ........................................ 4 B. Officers May Rely on Common Sense and Informed Inferences About Human Behavior ........................................................................... 7 C. Officers Need Not Rule Out Innocent Conduct Before Making an Investigatory Stop ................................................................... 9 D. Delaware v. Prouse -

Bail Jumping) (N.J.S.A

Approved 1/18/83 DEFAULT IN REQUIRED APPEARANCE (BAIL JUMPING) (N.J.S.A. 2C:29-7) The indictment charges the defendant with a violation of our criminal law, specifically N.J.S.A. 2C:29-7 which provides in pertinent part: "A person set at liberty by Court order with or without bail or who has been issued a summons upon condition that he will subsequently appear at a specified time and place in connection with any offense or any violation of law punishable by a period of incarceration commits an offense if, without lawful excuse, he fails to appear at that time and place." Therefore in order to convict the defendant of the crime charged in this indictment, the State has the burden of proving each of the following elements of this offense beyond a reasonable doubt: (1) That the defendant(s) was charged with the commission of a crime.1 The State has the burden of proving beyond a reasonable doubt that (named defendant) has been charged with the commission of a crime known as (state the nature of the crime). For the purpose of determining whether the State has proven this element, you are instructed that the crime known as is a violation of N.J.S.A. 2C: .2 (2) That (name defendant) has been issued a summons or set at liberty by court order with or without bail. (3) That there was in fact a condition that (he/she) would subsequently appear at a specified time and place in connection with that specific crime charged. -

The Right of Silence, the Presumption of Innocence, the Burden of Proof, and a Modest Proposal: a Reply to O'reilly Barton L

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 86 Article 10 Issue 2 Winter Winter 1996 The Right of Silence, the Presumption of Innocence, the Burden of Proof, and a Modest Proposal: A Reply to O'Reilly Barton L. Ingraham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation Barton L. Ingraham, The Right of Silence, the Presumption of Innocence, the Burden of Proof, and a Modest Proposal: A Reply to O'Reilly, 86 J. Crim. L. & Criminology 559 (1995-1996) This Criminal Law is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. 0091-4169/96/8602-0559 THE JOURL'4AL OF CRIMINAL LkW & CRIMINOLOGY Vol. 86, No. 2 Copyright @ 1996 by Northwestern University, School of Law Pntkd in U.S.A. ESSAY THE RIGHT OF SILENCE, TLE PRESUMPTION OF INNOCENCE, THE BURDEN OF PROOF, AND A MODEST PROPOSAL: A REPLY TO O'REILLY BARTON L. INGRAHAM* I. INTRODUCTION In the Fall 1994 issue of this Journal appeared an article by Greg- ory O'Reilly' commenting upon a recent amendment of English crim- inal procedure which allows judges and juries to consider as evidence of guilt both a suspect's failure to answer police questions during in- terrogation and a defendant's failure to testify at his criminal trial -

The Reasonable Doubt Rule and the Meaning of Innocence Scott E

University of Miami Law School University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository Articles Faculty and Deans 1989 The Reasonable Doubt Rule and the Meaning of Innocence Scott E. Sundby University of Miami School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.miami.edu/fac_articles Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminal Procedure Commons, and the Law and Society Commons Recommended Citation Scott E. Sundby, The Reasonable Doubt Rule and the Meaning of Innocence, 40 Hastings L.J. 457 (1989). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty and Deans at University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Articles The Reasonable Doubt Rule and the Meaning of Innocence by SCOTT E. SUNDBY* More grandiose prose rarely is found than that used to describe the role of the presumption of innocence in Anglo-American criminal law. The presumption has been called the "golden thread" that runs through- out the criminal law,1 heralded as the "cornerstone of Anglo-Saxon jus- ' 3 tice," 2 and identified as the "focal point of any concept of due process." Indeed, the presumption has become so central to the popular view of the criminal justice system, it has taken on "some of the characteristics of superstition."4 * Associate Professor, University of California, Hastings College of the Law. Profes- sors Jerome Hall, Louis Schwartz, and David Jung generously gave of their time to comment on earlier drafts. -

Legal Standard – Police Use of Deadly Force

Legal Standard – Police Use of Deadly Force In order to bring charges against a police officer for using deadly force, the State must be able to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that the officer’s use of deadly force was not justified. This legal standard remains the same, regardless of whether the factual determination is made by a county attorney or a grand jury. In order to charge second-degree manslaughter, the State must be able to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that the accused person acted with “culpable negligence” in creating an unreasonable risk of death or great bodily harm. “Culpable negligence” has been defined by Minnesota courts to mean acts that are grossly negligent combined with recklessness. In order to charge second-degree murder, the State must be able to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that the accused intended to cause the death of the victim. In order to charge first-degree murder, the State must be able to prove beyond a reasonable doubt not only that the accused intended to cause the victim’s death, but also that the action was premeditated. Those are the standards society recognizes when it comes to holding one criminally responsible for killing another. The statute authorizing a police officer’s use of deadly force in self-defense or defense of others is similar to that for civilians. However, courts have interpreted the provisions for law enforcement in a way that sets a high bar for obtaining a criminal conviction against a police officer for his or her use of force. Under Minnesota Statute § 609.066, subdivision 2, police officers in Minnesota are justified in using deadly force in the line of duty when it is necessary to protect the officer or another person from apparent death or great bodily harm.