The Knock-And-Announce Rule and Police Arrests: Evaluating Alternative Deterrents to Exclusion for Rule Violations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Warrantless Entries Into Private Homes by Mpd Officers

WARRANTLESS ENTRIES INTO PRIVATE HOMES BY MPD OFFICERS REPORT AND RECOMMENDATIONS OF THE POLICE COMPLAINTS BOARD TO MAYOR VINCENT C. GRAY, THE COUNCIL OF THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA, AND CHIEF OF POLICE CATHY L. LANIER June 12, 2013 POLICE COMPLAINTS BOARD Kurt Vorndran, Chair Assistant Chief Patrick A. Burke Iris Chavez Karl M. Fraser Margaret A. Moore 1400 I Street, NW, Suite 700 Washington, DC 20005 (202) 727-3838 Website: www.policecomplaints.dc.gov Table of Contents I. Introduction and Overview ............................................................................................1 II. Complaints Received by OPC .......................................................................................2 III. Current Policies and Practices .......................................................................................5 IV. Legal and Policy Concerns ............................................................................................7 V. Best Practices .................................................................................................................8 VI. Recommendations ........................................................................................................11 VII. Conclusion ...................................................................................................................13 I. INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW Pursuant to the Fourth Amendment of the United States Constitution, every citizen is guaranteed the right to be free from unreasonable searches and seizures. When the police -

Fourth Amendment--Requiring Probable Cause for Searches and Seizures Under the Plain View Doctrine Elsie Romero

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 78 Article 3 Issue 4 Winter Winter 1988 Fourth Amendment--Requiring Probable Cause for Searches and Seizures under the Plain View Doctrine Elsie Romero Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation Elsie Romero, Fourth Amendment--Requiring Probable Cause for Searches and Seizures under the Plain View Doctrine, 78 J. Crim. L. & Criminology 763 (1987-1988) This Supreme Court Review is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. 0091-4169/88/7804-763 THE JOURNAL OF CRIMINAL LAw & CRIMINOLOGY Vol. 78, No. 4 Copyright @ 1988 by Northwestern University, School of Law Printed in U.S.A. FOURTH AMENDMENT-REQUIRING PROBABLE CAUSE FOR SEARCHES AND SEIZURES UNDER THE PLAIN VIEW DOCTRINE Arizona v. Hicks, 107 S. Ct. 1149 (1987). I. INTRODUCTION The fourth amendment to the United States Constitution pro- tects individuals against arbitrary and unreasonable searches and seizures. 1 Fourth amendment protection has repeatedly been found to include a general requirement of a warrant based on probable cause for any search or seizure by a law enforcement agent.2 How- ever, there exist a limited number of "specifically established and -

Cops Or Robbers? How Georgia's Defense of Habitation Statute Applies to No-Knock Raids by Police Dimitri Epstein

Georgia State University Law Review Volume 26 Article 5 Issue 2 Winter 2009 March 2012 Cops or Robbers? How Georgia's Defense of Habitation Statute Applies to No-Knock Raids by Police Dimitri Epstein Follow this and additional works at: https://readingroom.law.gsu.edu/gsulr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Dimitri Epstein, Cops or Robbers? How Georgia's Defense of Habitation Statute Applies to No-Knock Raids by Police, 26 Ga. St. U. L. Rev. (2012). Available at: https://readingroom.law.gsu.edu/gsulr/vol26/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Publications at Reading Room. It has been accepted for inclusion in Georgia State University Law Review by an authorized editor of Reading Room. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Epstein: Cops or Robbers? How Georgia's Defense of Habitation Statute App COPS OR ROBBERS? HOW GEORGIA'S DEFENSE OF HABITATION STATUTE APPLIES TO NONO- KNOCK RAIDS BY POLICE Dimitri Epstein*Epstein * INTRODUCTION Late in the fall of 2006, the city of Atlanta exploded in outrage when Kathryn Johnston, a ninety-two-year old woman, died in a shoot-out with a police narcotics team.team.' 1 The police used a "no"no- knock" search warrant to break into Johnston's home unannounced.22 Unfortunately for everyone involved, Ms. Johnston kept an old revolver for self defense-not a bad strategy in a neighborhood with a thriving drug trade and where another elderly woman was recently raped.33 Probably thinking she was being robbed, Johnston managed to fire once before the police overwhelmed her with a "volley of thirty-nine" shots, five or six of which proved fatal.fata1.44 The raid and its aftermath appalled the nation, especially when a federal investigation exposed the lies and corruption leading to the incident. -

Fourth Amendment Litigation

Still the American Frontier: Fourth Amendment Litigation Deja Vishny September 2012 United States Constitution: The Fourth Amendment 1 Wisconsin State Constitution Article 1 Sec. 11 The Exclusionary Rule The Fruit of the Poisonous Tree Doctrine Attenuation Inevitable Discovery Independent Source Other exceptions to the Fruit of the Poisonous Tree Doctrine Applicability of the Fourth Amendment: The Expectation of Privacy Cars Sample list of areas the court has found to private and non-private. Deemed Non-Private: Standing & Overnight Guests Searches by Private Parties Requirement of Search Warrant Determination of probable cause Definition of the Home: Curtilage Permissible scope of search warrants Plain View Good Faith Knock and Announce Challenging Search Warrants Permissible warrantless entries and searches in homes and businesses Exception: Search Incident to Arrest Exception: Protective Sweep Exception: Plain View Exception: Exigent Circumstances : The Emergency Doctrine Exception: Exigent Circumstances: Hot Pursuit Exception: Imminent Destruction of Evidence Warrantless searches without entry Consent Searches Who may consent to entry and searches of the home Scope of consent Seizures of Persons: The Terry Doctrine Defining a Seizure Permissible Length of Temporary Seizures Permissible reasons for a Seizure: 2 Seizures bases on anonymous tips Seizures on Public Transportation Requests for Identification Roadblocks: Reasonable Suspicion: Frisk of Suspects Scope of Terry Frisk Seizures of Property Arrest Probable Cause for Arrest Warrantless -

Drawing a Line Between Terry and Miranda: the Degree and Duration of Restraint Katherine M

Drawing a Line between Terry and Miranda: The Degree and Duration of Restraint Katherine M. Swifit INTRODUCTION A felon answered the door in his underwear. Three police officers and three parole officers were there to search his apartment for a gun on the basis of a tip from his mother.! The police handcuffed him in the hallway outside his apartment, but told him he was not under ar- rest; the handcuffs were for his safety and the safety of the officers. Then they took him inside and asked about the gun, which he told them was in a shoebox on the table. The police never read the suspect his Miranda warnings. Was he "in custody"? Or was this merely a tem- porary detention? Mirandav Arizona' held that police may not interrogate a suspect who has been taken into custody without first issuing the familiar warnings Investigative stops, valid under Terry v Ohio,' are not sub- ject to Miranda's notice requirements.! Courts have not settled on a workable rule for determining custody in Terry stop cases. Part of the problem is that custody cases involve so many factors.! But more im- portant, coercive police behavior that would have required Miranda warnings in 1966 often is deemed reasonable under Terry today. This has led to a circuit split over whether coercive Terry stops constitute Miranda custody. The First, Fourth, and Eighth circuits hold t B.A., BJ. 1998, University of Missouri-Columbia; J.D. 2006, The University of Chicago. I The facts used in this example are drawn from United States v Newton, 369 F3d 659, 663 (2d Cir 2004). -

Level of Certainty Needed to Prove the Standard

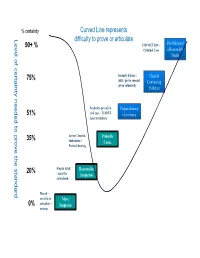

% certainty Curved Line represents Level of certainty needed to prove the standard needed toprove of certainty Level difficulty to prove or articulate 90+ % CONVICTION – Proof Beyond Criminal Case a Reasonable Doubt 75% Insanity defense / Clear & alibi / prove consent Convincing given voluntarily Evidence Needed to prevail in Preponderance 51% civil case – LIABLE of evidence Asset Forfeiture 35% Arrest / Search / Probable Indictment / Cause Pretrial hearing 20% Stop & Frisk Reasonable – must be Suspicion articulated Hunch – not able to Mere 0% articulate / Suspicion no stop Mere Suspicion – This term is used by the courts to refer to a hunch or intuition. We all experience this in everyday life but it is NOT enough “legally” to act on. It does not mean than an officer cannot observe the activity or person further without making contact. Mere suspicion cannot be articulated using any reasonably accepted facts or experiences. An officer may always make a consensual contact with a citizen without any justification. The officer will however have not justification to stop or hold a person under this situation. One might say something like, “There is just something about him that I don’t trust”. “I can’t quit put my finger on what it is about her.” “He looks out of place.” Reasonable Suspicion – Stop, Frisk for Weapons, *(New) Search of vehicle incident to arrest under Arizona V. Gant. The landmark case for reasonable suspicion is Terry v. Ohio, 392 U.S. 1 (1968) This level of proof is the justification police officers use to stop a person under suspicious circumstances (e.g. a person peaking in a car window at 2:00am). -

19-292 Torres V. Madrid (03/25/2021)

(Slip Opinion) OCTOBER TERM, 2020 1 Syllabus NOTE: Where it is feasible, a syllabus (headnote) will be released, as is being done in connection with this case, at the time the opinion is issued. The syllabus constitutes no part of the opinion of the Court but has been prepared by the Reporter of Decisions for the convenience of the reader. See United States v. Detroit Timber & Lumber Co., 200 U. S. 321, 337. SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES Syllabus TORRES v. MADRID ET AL. CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE TENTH CIRCUIT No. 19–292. Argued October 14, 2020—Decided March 25, 2021 Respondents Janice Madrid and Richard Williamson, officers with the New Mexico State Police, arrived at an Albuquerque apartment com- plex to execute an arrest warrant and approached petitioner Roxanne Torres, then standing near a Toyota FJ Cruiser. The officers at- tempted to speak with her as she got into the driver’s seat. Believing the officers to be carjackers, Torres hit the gas to escape. The officers fired their service pistols 13 times to stop Torres, striking her twice. Torres managed to escape and drove to a hospital 75 miles away, only to be airlifted back to a hospital in Albuquerque, where the police ar- rested her the next day. Torres later sought damages from the officers under 42 U. S. C. §1983. She claimed that the officers used excessive force against her and that the shooting constituted an unreasonable seizure under the Fourth Amendment. Affirming the District Court’s grant of summary judgment to the officers, the Tenth Circuit held that “a suspect’s continued flight after being shot by police negates a Fourth Amendment excessive-force claim.” 769 Fed. -

Reasonable Suspicion and Mere Hunches

Vanderbilt Law Review Volume 59 Issue 2 Article 3 3-2006 Reasonable Suspicion and Mere Hunches Craig S. Lerner Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr Part of the Criminal Law Commons Recommended Citation Craig S. Lerner, Reasonable Suspicion and Mere Hunches, 59 Vanderbilt Law Review 407 (2019) Available at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr/vol59/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vanderbilt Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Reasonable Suspicion and Mere Hunches Craig S. Lerner 59 Vand. L. Rev. 407 (2006) In Terry v. Ohio, Earl Warren held that police officers could temporarily detain a suspect, provided that they relied upon "specific, reasonable inferences," and not simply upon an "inchoate and unparticularized suspicion or 'hunch."' Since Terry, courts have strained to distinguish "reasonablesuspicion," which is said to arise from the cool analysis of objective and particularized facts, from "mere hunches," which are said to be subjective, generalized, unreasoned and therefore unreliable. Yet this dichotomy between facts and intuitions is built on sand. Emotions and intuitions are not obstacles to reason, but indispensable heuristic devices that allow people to process diffuse, complex information about their environment and make sense of the world. The legal rules governing police conduct are thus premised on a mistaken assumption about human cognition. This Article argues that the legal system can defer, to some extent, to police officers' intuitions without undermining meaningful protections against law enforcement overreaching. -

Studying the Exclusionary Rule in Search and Seizure Dallin H

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. Reprinted for private circulation from THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO LAW REVIEW Vol. 37, No.4, Summer 1970 Copyright 1970 by the University of Chicago l'RINTED IN U .soA. Studying the Exclusionary Rule in Search and Seizure Dallin H. OakS;- The exclusionary rule makes evidence inadmissible in court if law enforcement officers obtained it by means forbidden by the Constitu tion, by statute or by court rules. The United States Supreme Court currently enforces an exclusionary rule in state and federal criminal, proceedings as to four major types of violations: searches and seizures that violate the fourth amendment, confessions obtained in violation of the fifth and' sixth amendments, identification testimony obtained in violation of these amendments, and evidence obtained by methods so shocking that its use would violate the due process clause.1 The ex clusionary rule is the Supreme Court's sole technique for enforcing t Professor of Law, The University of Chicago; Executive Director-Designate, The American Bar Foundation. This study was financed by a three-month grant from the National Institute of Law Enforcement and Criminal Justice of the Law Enforcement Assistance Administration of the United States Department of Justice. The fact that the National Institute fur nished financial support to this study does not necessarily indicate the concurrence of the Institute in the statements or conclusions in this article_ Many individuals assisted the author in this study. Colleagues Hans Zeisel and Franklin Zimring gave valuable guidance on analysis, methodology and presentation. Colleagues Walter J. -

BAIL JUMPING in the THIRD DEGREE (Any Criminal Action Or Proceeding) Penal Law § 215.55 (Committed on Or After Sept

BAIL JUMPING IN THE THIRD DEGREE (Any Criminal Action or Proceeding) Penal Law § 215.55 (Committed on or after Sept. 8, 1983) The (specify) count is Bail Jumping in the Third Degree. Under our law, a person is guilty of Bail Jumping in the Third Degree when by court order he or she has been released from custody or allowed to remain at liberty, either upon bail or upon his or her own recognizance, upon condition that he or she will subsequently appear personally in connection with a criminal action or proceeding1, and when he or she does not appear personally on the required date or voluntarily within thirty days thereafter. In order for you to find the defendant guilty of this crime, the People are required to prove, from all of the evidence in the case, beyond a reasonable doubt, both of the following two elements: 1. That the defendant, (defendant’s name) was, by court order, released from custody or allowed to remain at liberty upon bail [or upon his/her own recognizance] upon condition that he/she would subsequently appear personally on (date) in (county) in connection with a criminal action or proceeding; and 2. That the defendant did not appear personally on the required date or voluntarily within thirty days thereafter. Note: If the affirmative defense does not apply, conclude as follows: If you find the People have proven beyond a reasonable doubt both of those elements, you must find the defendant guilty 1 If in issue, define criminal action or criminal proceeding in accordance with CPL 1.20(16) and (18). -

1/91 Crimpro Outline I) Basic Principles

Note: This outline is a textbook-only outline of Prof. S’s first syllabus. It does not cover in- class material (to any great degree) nor the second syllabus. Crimpro Outline I) Basic Principles – Police Discretion A) NEW FEDERALISM IDEA. Courts make a floor ; states can always give you more protection. B) What is a criminal case? How far does the doctrine stretch? 1) Criminal cases do not always (and, indeed, do not usually ) require jail and prison. 2) Having the state as a party does not always imply criminality in a case. 3) Basic definition: Something is criminal if the legislature has defined it as such. 4) This distinction can be incredibly important. Civil cases do not always carry the same rights and procedural safeguards as criminal cases. (a) *US v. LO Ward (US 1980, 2): Supreme Court holds that a penalty imposed upon persons discharging hazardous substances into navigable waters was a civil penalty, and thus reporting requirements attached thereto did not violate the Fifth Amendment. 5) Criminal/Civil distinction has two levels (a) Whether Congress/state actor, in establishing the penalizing mechanism, indicated either expressly or impliedly a preference for one label over the other. (b) Where the actor has indicated an intention, there is a further inquiry into to whether the statutory scheme is so punitive in effect or purpose to negate that intention. (US. v. Ward) 6) An example of judicial analysis: Commitment of Sex Offenders. (a) *Allen v. Illinois (US 1986, 2): Commitment proceedings under the Illinois Sexually Dangerous Persons Act were not criminal. -

State V Storm

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF IOWA No. 16–0362 Filed June 30, 2017 Amended September 18, 2017 STATE OF IOWA, Appellee, vs. CHRISTOPHER GEORGE STORM, Appellant. Appeal from the Iowa District Court for Dallas County, Randy V. Hefner, Judge. Defendant appeals his conviction claiming automobile exception to search warrant requirement should be abandoned. DISTRICT COURT JUDGMENT AFFIRMED. Daniel J. Rothman of McEnroe, Gotsdiner, Brewer, Steinbach & Rothman, P.C., for appellant. Thomas J. Miller, Attorney General, Kevin Cmelik and Louis S. Sloven, Assistant Attorneys General, for appellee. 2 WATERMAN, Justice. In this appeal, we must decide whether to abandon the automobile exception to the search warrant requirement under article I, section 8 of the Iowa Constitution. In State v. Gaskins, we did not reach that issue, but members of this court noted the rationale for the exception may be eroded by technological advances enabling police to obtain warrants from the scene of a traffic stop. 866 N.W.2d 1, 17 (Iowa 2015) (Cady, C.J., concurring specially). The defendant driver in today’s case was lawfully stopped for a seat belt violation. The deputy smelled marijuana and searched the vehicle, discovering marijuana packaged for resale. The defendant was charged with possession with intent to deliver in violation of Iowa Code section 124.401(1)(d) (2015). He filed a motion to suppress, claiming this warrantless search violated the Iowa Constitution because police can now obtain warrants electronically from the side of the road. The district court denied the motion after an evidentiary hearing that included testimony that it would have taken well over an hour to obtain a search warrant.