The Right of Silence, the Presumption of Innocence, the Burden of Proof, and a Modest Proposal: a Reply to O'reilly Barton L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Presumption of Innocence As a Counterfactual Principle Ferry De Jong & Leonie Van Lent*

This article is published in a peer-reviewed section of the Utrecht Law Review The Presumption of Innocence as a Counterfactual Principle Ferry de Jong & Leonie van Lent* 1. Introduction The presumption of innocence is widely, if not universally, recognized as one of the central principles of criminal justice, which is evidenced by its position in all international and regional human rights treaties as a standard of fair proceedings.1 Notwithstanding this seemingly firm normative position, there are strong indications that the presumption of innocence is in jeopardy on a practical as well as on a normative level. The presumption of innocence has always been much discussed, but in the last decade the topic has generated a particularly significant extent of academic work, both at the national and at the international level.2 The purport of the literature on this topic is twofold: many authors discuss developments in law and in the practice of criminal justice that curtail suspects’ rights and freedoms, and criticize these developments as being violations of the presumption of innocence. Several other authors search for the principle’s normative meaning and implications, some of whom take a critical stance on narrow interpretations of the principle, whereas others assert – by sometimes totally differing arguments – that the presumption of innocence has and should have a more limited normative meaning and scope than is generally attributed to it. An important argument for narrowing down the principle’s meaning or scope of application is the risk involved in a broad conception and a consequently broad field of applicability, viz. that its specific normative value becomes overshadowed and that concrete protection is hampered instead of furthered.3 The ever-increasing international interest in the topic is reflected also in the regulatory interest in the topic on the EU level. -

Cops Or Robbers? How Georgia's Defense of Habitation Statute Applies to No-Knock Raids by Police Dimitri Epstein

Georgia State University Law Review Volume 26 Article 5 Issue 2 Winter 2009 March 2012 Cops or Robbers? How Georgia's Defense of Habitation Statute Applies to No-Knock Raids by Police Dimitri Epstein Follow this and additional works at: https://readingroom.law.gsu.edu/gsulr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Dimitri Epstein, Cops or Robbers? How Georgia's Defense of Habitation Statute Applies to No-Knock Raids by Police, 26 Ga. St. U. L. Rev. (2012). Available at: https://readingroom.law.gsu.edu/gsulr/vol26/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Publications at Reading Room. It has been accepted for inclusion in Georgia State University Law Review by an authorized editor of Reading Room. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Epstein: Cops or Robbers? How Georgia's Defense of Habitation Statute App COPS OR ROBBERS? HOW GEORGIA'S DEFENSE OF HABITATION STATUTE APPLIES TO NONO- KNOCK RAIDS BY POLICE Dimitri Epstein*Epstein * INTRODUCTION Late in the fall of 2006, the city of Atlanta exploded in outrage when Kathryn Johnston, a ninety-two-year old woman, died in a shoot-out with a police narcotics team.team.' 1 The police used a "no"no- knock" search warrant to break into Johnston's home unannounced.22 Unfortunately for everyone involved, Ms. Johnston kept an old revolver for self defense-not a bad strategy in a neighborhood with a thriving drug trade and where another elderly woman was recently raped.33 Probably thinking she was being robbed, Johnston managed to fire once before the police overwhelmed her with a "volley of thirty-nine" shots, five or six of which proved fatal.fata1.44 The raid and its aftermath appalled the nation, especially when a federal investigation exposed the lies and corruption leading to the incident. -

Plea Bargaining As a Legal Transplant: a Good Idea for Troubled Criminal Justice Systems

Texas A&M University School of Law Texas A&M Law Scholarship Faculty Scholarship 3-2010 Plea Bargaining as a Legal Transplant: A Good Idea for Troubled Criminal Justice Systems Cynthia Alkon Texas A&M University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.tamu.edu/facscholar Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Cynthia Alkon, Plea Bargaining as a Legal Transplant: A Good Idea for Troubled Criminal Justice Systems, 19 Transnat'l L. & Contemp. Probs. 355 (2010). Available at: https://scholarship.law.tamu.edu/facscholar/268 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Texas A&M Law Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Texas A&M Law Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Plea Bargaining as a Legal Transplant: A Good Idea for Troubled Criminal Justice Systems? Cynthia Alkon* I. INTRODUCTION ......................................................... 356 II. TROUBLED CRIMINAL JUSTICE SYSTEMS: WHAT COUNTRIES FALL UNDER THIS CATEGORY?9 ......... 359 III. PLEA BARGAINING TRANSPLANTS: Two EXAMPLES.............. 360 A. The Republic of Georgia................................... 362 1. Background............................................ 362 2. Plea Bargaining ...................................... 363 a) Plea Bargaining in the Georgian Criminal Procedure Code .............................. 363 b) Plea Bargaining in Practice................ 365 B. Bosnia and Herzegovina.................................. -

Judge Donohue's Courtroom Procedures

JUDGE DONOHUE’S COURTROOM PROCEDURES I. INTRODUCTION A. Phone / Fax The office phone number is (541) 243-7805. During trials, your office, witnesses and family may leave messages with the judge’s judicial assistant. Those messages will be given to you by the courtroom clerk. Please call before sending faxes. The fax number is (541) 243-7877. You must first contact the judge’s judicial assistant before sending a fax transmission. There is a 10 page limit to the length of documents that can be sent by fax. We do not provide a fax service. We will not send an outgoing fax for you. B. Delivery of Documents You must file original documents via File and Serve. Please do not deliver originals to the judge or his judicial assistant unless otherwise specified in UTCR or SLR. You may hand- deliver to room 104, or email copies of documents to [email protected]. II. COURTROOM A. General Judge Donohue’s assigned courtroom is Courtroom #2 located on the second floor of the courthouse. B. Cell Phones / PDA’s Cell phones, personal digital assistant devices (PDA’s) and other types of personal electronic equipment may not be used in the courtroom without permission from the judge. If you bring them into the courtroom, you must turn them off or silence the ringer. C. Food, Drinks, Chewing Gum, Hats No food, drinks or chewing gum are permitted in the courtroom. Hats may not be worn in the courtroom. Ask the courtroom clerk if you need to seek an exception. JUDGE DONOHUE’S COURTROOM PROCEDURES (August 2019) Page 1 of 9 D. -

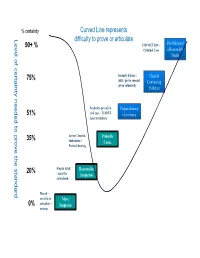

Level of Certainty Needed to Prove the Standard

% certainty Curved Line represents Level of certainty needed to prove the standard needed toprove of certainty Level difficulty to prove or articulate 90+ % CONVICTION – Proof Beyond Criminal Case a Reasonable Doubt 75% Insanity defense / Clear & alibi / prove consent Convincing given voluntarily Evidence Needed to prevail in Preponderance 51% civil case – LIABLE of evidence Asset Forfeiture 35% Arrest / Search / Probable Indictment / Cause Pretrial hearing 20% Stop & Frisk Reasonable – must be Suspicion articulated Hunch – not able to Mere 0% articulate / Suspicion no stop Mere Suspicion – This term is used by the courts to refer to a hunch or intuition. We all experience this in everyday life but it is NOT enough “legally” to act on. It does not mean than an officer cannot observe the activity or person further without making contact. Mere suspicion cannot be articulated using any reasonably accepted facts or experiences. An officer may always make a consensual contact with a citizen without any justification. The officer will however have not justification to stop or hold a person under this situation. One might say something like, “There is just something about him that I don’t trust”. “I can’t quit put my finger on what it is about her.” “He looks out of place.” Reasonable Suspicion – Stop, Frisk for Weapons, *(New) Search of vehicle incident to arrest under Arizona V. Gant. The landmark case for reasonable suspicion is Terry v. Ohio, 392 U.S. 1 (1968) This level of proof is the justification police officers use to stop a person under suspicious circumstances (e.g. a person peaking in a car window at 2:00am). -

1 Hon. Joel M. Cohen Part 3 – Practices and Procedures

HON. JOEL M. COHEN PART 3 – PRACTICES AND PROCEDURES (revised September 14, 2020) Supreme Court of the State of New York Commercial Division 60 Centre Street, Courtroom 208 New York, NY 10007 Part Clerk/Courtroom Phone: 646-386-3275 Chambers Phone: 646-386-4927 Principal Court Attorney: Kartik Naram, Esq. ([email protected]) Law Clerk: Herbert Z. Rosen, Esq. ([email protected]) Courtroom Part Clerk: Sharon Hill ([email protected]) Chambers Email Address: [email protected] Courtroom hours are from 9:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. Lunch recess is from 1 p.m. to 2:15 p.m. The courtroom is closed during that time. Preliminary, Compliance, and Status Conferences generally are held on Tuesdays beginning at 9:30 a.m. Pre-trial Conferences and oral argument on motions will be held as scheduled by the Court. I. GENERAL A. The Rules of the Commercial Division, 22 NYCRR 202.70, are incorporated herein by reference, subject to minor modifications described below. B. The Court strongly encourages substantive participation in court proceedings by women and diverse lawyers, who historically have been underrepresented in the commercial bar. The Court urges litigants to be mindful of in-court advocacy opportunities for such lawyers who have not previously had substantial court experience in commercial cases, as well as less experienced lawyers generally (i.e. lawyers practicing for five years or less). A representation that oral argument on a motion will be handled or shared by such a lawyer will weigh in favor of holding a hearing when otherwise the motion would be decided on the papers. -

Cops and Pleas: Police Officers' Influence on Plea Bargaining

JONATHAN ABEL Cops and Pleas: Police Officers' Influence on Plea Bargaining AB S TRACT. Police officers play an important, though little-understood, role in plea bargain- ing. This Essay examines the many ways in which prosecutors and police officers consult, collab- orate, and clash with each other over plea bargaining. Using original interviews with criminal justice officials from around the country, this Essay explores the mechanisms of police involve- ment in plea negotiations and the implications of this involvement for both plea bargaining and policing. Ultimately, police influence in the arena of plea bargaining -long thought the exclusive domain of prosecutors -calls into question basic assumptions about who controls the prosecu- tion team. A U T H 0 R. Fellow, Stanford Constitutional Law Center. I am grateful to Kim Jackson and her colleagues at the Yale Law journal for their invaluable suggestions. I also want to thank col- leagues, friends, and family who read drafts and talked through the issues with me. A short list includes Liora Abel, Greg Ablavsky, Stephanos Bibas, Jack Chin, Barbara Fried, Colleen Honigs- berg, Cathy Hwang, Shira Levine, Michael McConnell, Sonia Moss, Howard Shneider, Robert Weisberg, and the riders of A.C. Transit's "0" Bus. 1730 ESSAY CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1732 1. THE SEPARATION OF POWERS WITHIN THE PROSECUTION TEAM 1735 A. Academic Accounts 1736 1. Scholarship on the Police Role in Plea Bargaining 1737 2. Scholarship on the Separation of Powers in Plea Bargaining 1741 B. Prosecutor and Police Accounts of the Separation of Powers in Plea Bargaining 1743 II. POLICE INFLUENCE ON PLEA BARGAINING 1748 A. -

Disclosure and Accuracy in the Guilty Plea Process Kevin C

Hastings Law Journal Volume 40 | Issue 5 Article 2 1-1989 Disclosure and Accuracy in the Guilty Plea Process Kevin C. McMunigal Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Kevin C. McMunigal, Disclosure and Accuracy in the Guilty Plea Process, 40 Hastings L.J. 957 (1989). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal/vol40/iss5/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Disclosure and Accuracy in the Guilty Plea Process by KEVIN C. MCMUNIGAL* Consider the following disclosure problem. The government indicts a defendant on an armed robbery charge arising from a violent mugging. The prosecution's case is based entirely on the testimony of the victim, who identified the defendant from police photographs of persons with a record of similar violent crime. With only the victim's testimony to rely on, the prosecutor is unsure of her ability to obtain a conviction at trial. She offers the defendant a guilty plea limiting his sentencing exposure to five years, a significant concession in light of the defendant's substantial prior record and the fact that the charged offense carries a maximum penalty of fifteen years incarceration. As trial nears, the victim's confi- dence in the identification appears to wane. The robbery took place at night. He was frightened and saw his assailant for a matter of seconds. -

Justice in Jeopardy

RWANDA JUSTICE IN JEOPARDY THE FIRST INSTANCE TRIAL OF VICTOIRE INGABIRE Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 3 million supporters, members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaign to end grave abuses of human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. First published in 2013 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom © Amnesty International 2013 Index: AFR 47/001/2013 English Original language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. The copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. To request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Cover photo: Victoire Ingabire at the High Court of Kigali, Rwanda, November 2011. © STEVE TERRILL/AFP/Getty Images amnesty.org CONTENTS 1. Acronyms.................................................................................................................5 -

Plea Bargaining and International Criminal Justice

Plea Bargaining and International Criminal Justice Jenia lontcheva Turner* TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION .................................................... 219 II. PLEA BARGAINING AT THE NATIONAL LEVEL ............. ............. 221 A. Common Law Systems ...................................... 221 B. Civil Law Systems ........................ ................ 224 III. PLEA BARGAINING AT INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL COURTS ... .......... 226 A. The Introduction ofPlea Bargaining ........................ 226 B. Conditionsfor Valid Plea Agreements .................. 229 C. Conditionsfor Valid Guilty Pleas .............................. 232 D. Sentencing Consequences of Guilty Pleas.............. ...... 237 IV. THE DEBATE OVER PLEA BARGAINING AT INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL COURTS......................................................... 239 I. INTRODUCTION Over the last two decades, plea bargaining has spread beyond the countries where it originated-the United States and other common law jurisdictions-and has become a global phenomenon.' Plea bargaining is spreading rapidly to civil law countries that previously viewed the practice with skepticism. And it has now arrived at international criminal courts. 2 While domestic plea bargaining is often limited to non-violent crimes,3 the international courts allow sentence negotiations for even the most heinous offenses, including genocide and crimes against humanity.4 Its use remains highly controversial, and debates about plea bargaining in international courts continue in court opinions and academic -

The Myth of the Presumption of Innocence

Texas Law Review See Also Volume 94 Response The Myth of the Presumption of Innocence Brandon L. Garrett* I. Introduction Do we have a presumption of innocence in this country? Of course we do. After all, we instruct criminal juries on it, often during jury selection, and then at the outset of the case and during final instructions before deliberations. Take this example, delivered by a judge at a criminal trial in Illinois: "Under the law, the Defendant is presumed to be innocent of the charges against him. This presumption remains with the Defendant throughout the case and is not overcome until in your deliberations you are convinced beyond a reasonable doubt that the Defendant is guilty."' Perhaps the presumption also reflects something more even, a larger commitment enshrined in a range of due process and other constitutional rulings designed to protect against wrongful convictions. The defense lawyer in the same trial quoted above said in his closings: [A]s [the defendant] sits here right now, he is presumed innocent of these charges. That is the corner stone of our system of justice. The best system in the world. That is a presumption that remains with him unless and until the State can prove him guilty beyond2 a reasonable doubt. That's the lynchpin in the system ofjustice. Our constitutional criminal procedure is animated by that commitment, * Justice Thurgood Marshall Distinguished Professor of Law, University of Virginia School of Law. 1. Transcript of Record at 13, People v. Gonzalez, No. 94 CF 1365 (Ill.Cir. Ct. June 12, 1995). 2. -

The “Radical” Notion of the Presumption of Innocence

EXECUTIVE SESSION ON THE FUTURE OF JUSTICE POLICY THE “RADICAL” MAY 2020 Tracey Meares, NOTION OF THE Justice Collaboratory, Yale University Arthur Rizer, PRESUMPTION R Street Institute OF INNOCENCE The Square One Project aims to incubate new thinking on our response to crime, promote more effective strategies, and contribute to a new narrative of justice in America. Learn more about the Square One Project at squareonejustice.org The Executive Session was created with support from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation as part of the Safety and Justice Challenge, which seeks to reduce over-incarceration by changing the way America thinks about and uses jails. 04 08 14 INTRODUCTION THE CURRENT STATE OF WHY DOES THE PRETRIAL DETENTION PRESUMPTION OF INNOCENCE MATTER? 18 24 29 THE IMPACT OF WHEN IS PRETRIAL WHERE DO WE GO FROM PRETRIAL DETENTION DETENTION HERE? ALTERNATIVES APPROPRIATE? TO AND SAFEGUARDS AROUND PRETRIAL DETENTION 33 35 37 CONCLUSION ENDNOTES REFERENCES 41 41 42 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS AUTHOR NOTE MEMBERS OF THE EXECUTIVE SESSION ON THE FUTURE OF JUSTICE POLICY 04 THE ‘RADICAL’ NOTION OF THE PRESUMPTION OF INNOCENCE “It was the smell of [] death, it was the death of a person’s hope, it was the death of a person’s ability to live the American dream.” That is how Dr. Nneka Jones Tapia described the Cook County Jail where she served as the institution’s warden (from May 2015 to March 2018). This is where we must begin. EXECUTIVE SESSION ON THE FUTURE OF JUSTICE POLICY 05 THE ‘RADICAL’ NOTION OF THE PRESUMPTION OF INNOCENCE Any discussion of pretrial detention must Let’s not forget that Kalief Browder spent acknowledge that we subject citizens— three years of his life in Rikers, held on presumed innocent of the crimes with probable cause that he had stolen a backpack which they are charged—to something containing money, a credit card, and an iPod that resembles death.