Search Warrant Manual

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cops Or Robbers? How Georgia's Defense of Habitation Statute Applies to No-Knock Raids by Police Dimitri Epstein

Georgia State University Law Review Volume 26 Article 5 Issue 2 Winter 2009 March 2012 Cops or Robbers? How Georgia's Defense of Habitation Statute Applies to No-Knock Raids by Police Dimitri Epstein Follow this and additional works at: https://readingroom.law.gsu.edu/gsulr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Dimitri Epstein, Cops or Robbers? How Georgia's Defense of Habitation Statute Applies to No-Knock Raids by Police, 26 Ga. St. U. L. Rev. (2012). Available at: https://readingroom.law.gsu.edu/gsulr/vol26/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Publications at Reading Room. It has been accepted for inclusion in Georgia State University Law Review by an authorized editor of Reading Room. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Epstein: Cops or Robbers? How Georgia's Defense of Habitation Statute App COPS OR ROBBERS? HOW GEORGIA'S DEFENSE OF HABITATION STATUTE APPLIES TO NONO- KNOCK RAIDS BY POLICE Dimitri Epstein*Epstein * INTRODUCTION Late in the fall of 2006, the city of Atlanta exploded in outrage when Kathryn Johnston, a ninety-two-year old woman, died in a shoot-out with a police narcotics team.team.' 1 The police used a "no"no- knock" search warrant to break into Johnston's home unannounced.22 Unfortunately for everyone involved, Ms. Johnston kept an old revolver for self defense-not a bad strategy in a neighborhood with a thriving drug trade and where another elderly woman was recently raped.33 Probably thinking she was being robbed, Johnston managed to fire once before the police overwhelmed her with a "volley of thirty-nine" shots, five or six of which proved fatal.fata1.44 The raid and its aftermath appalled the nation, especially when a federal investigation exposed the lies and corruption leading to the incident. -

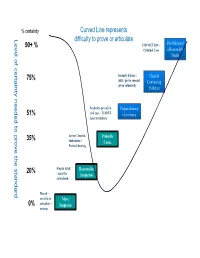

Level of Certainty Needed to Prove the Standard

% certainty Curved Line represents Level of certainty needed to prove the standard needed toprove of certainty Level difficulty to prove or articulate 90+ % CONVICTION – Proof Beyond Criminal Case a Reasonable Doubt 75% Insanity defense / Clear & alibi / prove consent Convincing given voluntarily Evidence Needed to prevail in Preponderance 51% civil case – LIABLE of evidence Asset Forfeiture 35% Arrest / Search / Probable Indictment / Cause Pretrial hearing 20% Stop & Frisk Reasonable – must be Suspicion articulated Hunch – not able to Mere 0% articulate / Suspicion no stop Mere Suspicion – This term is used by the courts to refer to a hunch or intuition. We all experience this in everyday life but it is NOT enough “legally” to act on. It does not mean than an officer cannot observe the activity or person further without making contact. Mere suspicion cannot be articulated using any reasonably accepted facts or experiences. An officer may always make a consensual contact with a citizen without any justification. The officer will however have not justification to stop or hold a person under this situation. One might say something like, “There is just something about him that I don’t trust”. “I can’t quit put my finger on what it is about her.” “He looks out of place.” Reasonable Suspicion – Stop, Frisk for Weapons, *(New) Search of vehicle incident to arrest under Arizona V. Gant. The landmark case for reasonable suspicion is Terry v. Ohio, 392 U.S. 1 (1968) This level of proof is the justification police officers use to stop a person under suspicious circumstances (e.g. a person peaking in a car window at 2:00am). -

Warrantless Workplace Searches of Government

WARRANTLESS WORKPLACE within which the principles outlined in SEARCHES OF GOVERNMENT O’Connor for “workplace” searches by EMPLOYEES government supervisors can be understood and applied. In sum, when a government supervisor is considering the search of a Bryan R. Lemons government employee’s workspace, a two- Branch Chief part analysis can be utilized to simplify the process. First, determine whether the There are a variety of reasons why employee has a reasonable expectation of a government supervisor might wish to privacy in the area to be searched. If a search a government employee’s reasonable expectation of privacy does workplace. For example, a supervisor exist, then consider how that expectation might wish to conduct a search to locate a can be defeated.2 Before turning to those needed file or document; the supervisor issues, however, it is necessary to first might wish to search an employee’s define exactly what is meant by the term workplace to discover whether the “workplace.” employee is misusing government property, such as a government-owned DEFINING THE “WORKPLACE” computer; or, a supervisor might seek to search an employee’s workplace because “Workplace,” as used in this he has information that the employee is article, “includes those areas and items committing a crime, such as using the that are related to work and are generally Internet to download child pornography. within the employer’s control.”3 This would include such areas as offices, desks, In situations where a public filing cabinets, and computers. However, employer -

“Canned History”: American Newsreels and The

“Canned History”: American Newsreels and the Commodification of Reality, 1927-1945 By Joseph E.J. Clark B.A., University of British Columbia, 1999 M.A., University of British Columbia, 2001 M.A., Brown University, 2004 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of American Civilization at Brown University Providence, Rhode Island May, 2011 © Copyright 2010, by Joseph E.J. Clark This dissertation by Joseph E.J. Clark is accepted in its present form by the Department of American Civilization as satisfying the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date:____________ _________________________________ Professor Susan Smulyan, Co-director Date:____________ _________________________________ Professor Philip Rosen, Co-director Recommended to the Graduate Council Date:____________ _________________________________ Professor Lynne Joyrich, Reader Approved by the Graduate Council Date:____________ _________________________________ Dean Peter Weber, Dean of the Graduate School iii Curriculum Vitae Joseph E.J. Clark Date of Birth: July 30, 1975 Place of Birth: Beverley, United Kingdom Education: Ph.D. American Civilization, Brown University, 2011 Master of Arts, American Civilization, Brown University, 2004 Master of Arts, History, University of British Columbia, 2001 Bachelor of Arts, University of British Columbia, 1999 Teaching Experience: Sessional Instructor, Department of Gender, Sexuality, and Women’s Studies, Simon Fraser University, Spring 2010 Sessional Instructor, Department of History, Simon Fraser University, Fall 2008 Sessional Instructor, Department of Theatre, Film, and Creative Writing, University of British Columbia, Spring 2008 Teaching Fellow, Department of American Civilization, Brown University, 2006 Teaching Assistant, Brown University, 2003-2004 Publications: “Double Vision: World War II, Racial Uplift, and the All-American Newsreel’s Pedagogical Address,” in Charles Acland and Haidee Wasson, eds. -

BAIL JUMPING in the THIRD DEGREE (Any Criminal Action Or Proceeding) Penal Law § 215.55 (Committed on Or After Sept

BAIL JUMPING IN THE THIRD DEGREE (Any Criminal Action or Proceeding) Penal Law § 215.55 (Committed on or after Sept. 8, 1983) The (specify) count is Bail Jumping in the Third Degree. Under our law, a person is guilty of Bail Jumping in the Third Degree when by court order he or she has been released from custody or allowed to remain at liberty, either upon bail or upon his or her own recognizance, upon condition that he or she will subsequently appear personally in connection with a criminal action or proceeding1, and when he or she does not appear personally on the required date or voluntarily within thirty days thereafter. In order for you to find the defendant guilty of this crime, the People are required to prove, from all of the evidence in the case, beyond a reasonable doubt, both of the following two elements: 1. That the defendant, (defendant’s name) was, by court order, released from custody or allowed to remain at liberty upon bail [or upon his/her own recognizance] upon condition that he/she would subsequently appear personally on (date) in (county) in connection with a criminal action or proceeding; and 2. That the defendant did not appear personally on the required date or voluntarily within thirty days thereafter. Note: If the affirmative defense does not apply, conclude as follows: If you find the People have proven beyond a reasonable doubt both of those elements, you must find the defendant guilty 1 If in issue, define criminal action or criminal proceeding in accordance with CPL 1.20(16) and (18). -

Legal-Process Guidelines for Law Enforcement

Legal Process Guidelines Government & Law Enforcement within the United States These guidelines are provided for use by government and law enforcement agencies within the United States when seeking information from Apple Inc. (“Apple”) about customers of Apple’s devices, products and services. Apple will update these Guidelines as necessary. All other requests for information regarding Apple customers, including customer questions about information disclosure, should be directed to https://www.apple.com/privacy/contact/. These Guidelines do not apply to requests made by government and law enforcement agencies outside the United States to Apple’s relevant local entities. For government and law enforcement information requests, Apple complies with the laws pertaining to global entities that control our data and we provide details as legally required. For all requests from government and law enforcement agencies within the United States for content, with the exception of emergency circumstances (defined in the Electronic Communications Privacy Act 1986, as amended), Apple will only provide content in response to a search issued upon a showing of probable cause, or customer consent. All requests from government and law enforcement agencies outside of the United States for content, with the exception of emergency circumstances (defined below in Emergency Requests), must comply with applicable laws, including the United States Electronic Communications Privacy Act (ECPA). A request under a Mutual Legal Assistance Treaty or the Clarifying Lawful Overseas Use of Data Act (“CLOUD Act”) is in compliance with ECPA. Apple will provide customer content, as it exists in the customer’s account, only in response to such legally valid process. -

THE SEARCH for COMPACT BINARY COALESCENCE in ASSOCIATION with SHORT GRBS with LIGO/VIRGO S5/VSR1 DATA by Nickolas V Fotopoulos

THE SEARCH FOR COMPACT BINARY COALESCENCE IN ASSOCIATION WITH SHORT GRBS WITH LIGO/VIRGO S5/VSR1 DATA By Nickolas V Fotopoulos ATHESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN PHYSICS at The University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee May 2010 THE SEARCH FOR COMPACT BINARY COALESCENCE IN ASSOCIATION WITH SHORT GRBS WITH LIGO/VIRGO S5/VSR1 DATA By Nickolas V Fotopoulos ATHESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN PHYSICS at The University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee May 2010 Jolien Creighton Date Graduate School Approval Date ii THE SEARCH FOR COMPACT BINARY COALESCENCE IN ASSOCIATION WITH SHORT GRBS WITH LIGO/VIRGO S5/VSR1 DATA By Nickolas V Fotopoulos The University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee, 2010 Under the Supervision of Professor Jolien Creighton ABSTRACT During LIGO’s fifth science run (S5) and Virgo’s first science run (VSR1), x-ray and gamma-ray observatories recorded 33 short, hard gamma-ray bursts (short GRBs), 22 of which had high quality data in two or more detectors. The most convincing explanation for the majority of short GRBs is that in the final stages of an inspiral between a neutron star and a companion compact object, the neutron star is tidally disrupted, providing material to accrete, heat, and eject on sub-second timescales. I describe a search for the gravitational-wave signatures of compact binary coalescence in the vicinity of short GRBs that occurred during S5/VSR1. Jolien Creighton Date iii © Copyright 2010 by Nickolas V Fotopoulos iv to Mom and Bub v TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments ix List of Tables xi List of Figures xiv 1 Introduction 1 2 Short GRBs, CBCs, and gravitational waves 3 2.1 Short gamma-ray burst phenomenology . -

What to Do When You Are Served with a Search Warrant by Manny A

AN A.S. PRATT PUBLICATION APRIL 2016 PRATT’S PRATT’S VOL. 2 • NO. 3 PRIVACY & CYBERSECURITY LAW CYBERSECURITY & PRIVACY PRATT’S PRIVACY & CYBERSECURITY REPORT LAW REPORT EDITOR’S NOTE: SOMETHING FOR EVERYONE! THE FTC, UNFAIR PRACTICES, AND Steven A. Meyerowitz CYBERSECURITY: TWO STEPS FORWARD, AND TWO STEPS BACK WHAT TO DO WHEN YOU ARE SERVED WITH A David Bender SEARCH WARRANT APRIL Manny A. Abascal and Robert E. Sims DRONES AT HOME: DHS PUBLISHES BEST PRACTICES FOR PROTECTING PRIVACY, CIVIL PRESIDENT OBAMA SIGNS CYBERSECURITY RIGHTS, AND CIVIL LIBERTIES IN DOMESTIC 2016 ACT OF 2015 TO ENCOURAGE CYBERSECURITY UAS PROGRAMS INFORMATION SHARING Charles A. Blanchard, David J. Weiner, Kenneth L. Wainstein, Keith M. Gerver, Tom McSorley, and Elizabeth T.M. Fitzpatrick and Peter T. Carey VOL. VOL. A SKIMPY RISK ANALYSIS IS RISKY BUSINESS 2 FOR HIPAA COVERED ENTITIES AND • BUSINESS ASSOCIATES NO. Kimberly C. Metzger 3 What to Do When You Are Served With a Search Warrant By Manny A. Abascal and Robert E. Sims* Most business executives and officers lack the training and preparation to deal effec- tively with a search warrant. In order to protect privacy and other rights, this article sets forth the basic principles that should govern preparation for, and response to, a search warrant. State and federal law enforcement agencies continue to increase their investigation and prosecution of white collar crime, particularly relating to the securities and health- care industries. The search warrant has become a regular method authorities use to obtain evidence. Law enforcement officers executing a warrant typically arrive at corporate offices with no prior notice, armed with a search warrant entitling them to seize original business records, including computer records. -

Section 3: the Search & Call Process in the United Church of Christ

United Church of Christ SEARCH AND CALL A Pilgrimage through Transitions and New Beginnings SECTION THREE THE SEARCH AND CALL PROCESS in The United Church of Christ “I am confident of this, that the one who began a good work among you will bring it to completion….” Philippians 1:6a SECTION THREE THE SEARCH AND CALL PROCESS in The United Church of Christ I am confident of this, that the one who began a good work among you will bring it to completion…. Philippians 1:6a “A Call, not a Job; a Vocation, not an Occupation” APPROACHING THE TASK: GOD’S COMMITTEE Selecting a Search Committee Just as the local church is not “our” church but rather God’s, so too the Search Committee is really God’s committee. A search for a new pastor is one of the most spiritual ministries in the church. The selection of Search Committee members is a task that is approached with prayer, wisdom, sensitivity, and awareness that God may be calling certain church members to consider serving in this particular capacity.1 One “best practice” for committee selection includes publicizing the criteria for membership on the Search Committee and inviting persons in the congregation Submitting to submit nominations to the governing board. nominations is one of Submitting nominations is one of the many ways that the many ways that the entire congregation can be informed about and included in the search process; it should be made the entire clear, however, that not all nominees will be congregation can be selected. Those who submit nominations should informed about and include a brief description of the reasons why that included in the search person would be an asset to the committee. -

A Call from the Panopticon to the Judicial Chamber “Expect Privacy!”

Journal of International Commercial Law and Technology Vol.1, Issue 2 (2006) A Call From the Panopticon to the Judicial Chamber “Expect Privacy!” Julia Alpert Gladstone Bryant University Smithfield, RI,USA Abstract Privacy is necessary in order for one to develop physically, mentally and affectively. Autonomy and self definition have been recognized by the United States Supreme Court as being values of privacy. In our technologically advanced, and fear driven society, however, our right to privacy has been severely eroded. Due to encroachment by government and business we have a diminished expectation of privacy. This article examines the detriments to self and society which result from a reduced sphere of privacy, as well as offering a modest suggestion for a method to reintroduce an improved conception of privacy into citizens’ lives. Keywords: Privacy, Technology, Judiciary, Autonomy, Statute INTRODUCTION Citizens often pay scant attention to their privacy rights until a consciousness raising event, such as the late 2005 exposure of the unauthorized wiretapping performed by the United States Executive Branch, heightens their interest and concern to protect previously dormant privacy rights. The scholarly literature on privacy is plentiful which broadly explains privacy as a liberty or property right, or a condition of inner awareness, and explanations of invasions of privacy are also relevant. This article seeks to explain why privacy remains under prioritized in most people’s lives, and yet, privacy is held as a critical, if not, fundamental right. Privacy is defined according to social constructs that evolve with time, but it is valued, differently. It is valued as a means to control one’s life. -

Conflict of the Criminal Statute of Limitations with Lesser Offenses at Trial

William & Mary Law Review Volume 37 (1995-1996) Issue 1 Article 10 October 1995 Conflict of the Criminal Statute of Limitations with Lesser Offenses at Trial Alan L. Adlestein Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr Part of the Criminal Law Commons Repository Citation Alan L. Adlestein, Conflict of the Criminal Statute of Limitations with Lesser Offenses at Trial, 37 Wm. & Mary L. Rev. 199 (1995), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr/vol37/iss1/10 Copyright c 1995 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr CONFLICT OF THE CRIMINAL STATUTE OF LIMITATIONS WITH LESSER OFFENSES AT TRIAL ALAN L. ADLESTEIN I. INTRODUCTION ............................... 200 II. THE CRIMINAL STATUTE OF LIMITATIONS AND LESSER OFFENSES-DEVELOPMENT OF THE CONFLICT ........ 206 A. Prelude: The Problem of JurisdictionalLabels ..... 206 B. The JurisdictionalLabel and the CriminalStatute of Limitations ................ 207 C. The JurisdictionalLabel and the Lesser Offense .... 209 D. Challenges to the Jurisdictional Label-In re Winship, Keeble v. United States, and United States v. Wild ..................... 211 E. Lesser Offenses and the Supreme Court's Capital Cases- Beck v. Alabama, Spaziano v. Florida, and Schad v. Arizona ........................... 217 1. Beck v. Alabama-LegislativePreclusion of Lesser Offenses ................................ 217 2. Spaziano v. Florida-Does the Due Process Clause Require Waivability? ....................... 222 3. Schad v. Arizona-The Single Non-Capital Option ....................... 228 F. The Conflict Illustrated in the Federal Circuits and the States ....................... 230 1. The Conflict in the Federal Circuits ........... 232 2. The Conflict in the States .................. 234 III. -

Search Warrants: Informants Jeff Welty UNC School of Government October 2018

Search Warrants: Informants Jeff Welty UNC School of Government October 2018 Objectives • Be able to categorize sources of information accurately as officers, citizens, confidential informants, or anonymous tipsters. • Know the legal tests for when information from each type of source is sufficient to provide probable cause. • Know the legal rules regarding staleness of information. • Be able to apply the above knowledge in the context of actual search warrant applications. Most Search Warrant Cases Involve Informants • “Studies in Atlanta, Boston, San Diego, and Cleveland [found] that 92 percent of the 1,200 federal warrants issued in those cities relied on an informant.” • Alexandra Natapoff, Snitching: The Institutional and Communal Consequences, 73 U. Cin. L. Rev. 645 (2004) • What fraction of your search warrant cases involve informants? 1 It Is OK for Officers to Rely on Information from Others • “The affidavit may be based on hearsay information and need not reflect the direct personal observations of the affiant.” • State v. Campbell, 282 N.C. 185 (1972) Categories of Sources Officers and Citizens Confidential Informants Anonymous Tipsters 2 Information from Other Officers • “[I]t is well‐established that where the named informant is a police officer, his reliability will be presumed.” • State v. Caldwell, 53 N.C. App. 1 (1981) • Does this presumption of reliability make sense? • Are there circumstances where you would not presume the reliability of information from another officer? • Even if it is reliable, it won’t always provide probable cause • Limited information • Conclusory information • Stale information • Poor basis of knowledge Information from Victims and Other Citizens • “The fact that [the citizen informant] was named and identified .