General Assembly •••.•••••••••• 1 - 4 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Condominiums and Shared Sovereignty | 1

Condominiums and Shared Sovereignty | 1 Condominiums And Shared Sovereignty Abstract As the United Kingdom (UK) voted to leave the European Union (EU), the future of Gibraltar, appears to be in peril. Like Northern Ireland, Gibraltar borders with EU territory and strongly relies on its ties with Spain for its economic stability, transports and energy supplies. Although the Gibraltarian government is struggling to preserve both its autonomy with British sovereignty and accession to the European Union, the Spanish government states that only a form of joint- sovereignty would save Gibraltar from the same destiny as the rest of UK in case of complete withdrawal from the EU, without any accession to the European Economic Area (Hard Brexit). The purpose of this paper is to present the concept of Condominium as a federal political system based on joint-sovereignty and, by presenting the existing case of Condominiums (i.e. Andorra). The paper will assess if there are margins for applying a Condominium solution to Gibraltar. Condominiums and Shared Sovereignty | 2 Condominium in History and Political Theory The Latin word condominium comes from the union of the Latin prefix con (from cum, with) and the word dominium (rule). Watts (2008: 11) mentioned condominiums among one of the forms of federal political systems. As the word suggests, it is a form of shared sovereignty involving two or more external parts exercising a joint form of sovereignty over the same area, sometimes in the form of direct control, and sometimes while conceding or maintaining forms of self-government on the subject area, occasionally in a relationship of suzerainty (Shepheard, 1899). -

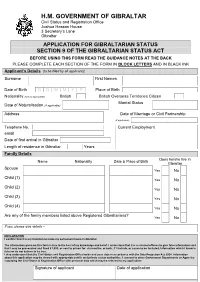

Application for Gibraltarian Status (Section 9)

H.M. GOVERNMENT OF GIBRALTAR Civil Status and Registration Office Joshua Hassan House 3 Secretary’s Lane Gibraltar APPLICATION FOR GIBRALTARIAN STATUS SECTION 9 OF THE GIBRALTARIAN STATUS ACT BEFORE USING THIS FORM READ THE GUIDANCE NOTES AT THE BACK PLEASE COMPLETE EACH SECTION OF THE FORM IN BLOCK LETTERS AND IN BLACK INK Applicant’s Details (to be filled by all applicants) Surname First Names Date of Birth D D M M Y Y Place of Birth Nationality (tick as appropriate) British British Overseas Territories Citizen Marital Status Date of Naturalisation (if applicable) Address Date of Marriage or Civil Partnership (if applicable) Telephone No. Current Employment email Date of first arrival in Gibraltar Length of residence in Gibraltar Years Family Details Does he/she live in Name Nationality Date & Place of Birth Gibraltar Spouse Yes No Child (1) Yes No Child (2) Yes No Child (3) Yes No Child (4) Yes No Are any of the family members listed above Registered Gibraltarians? Yes No If yes, please give details – DECLARATION I confirm that it is my intention to make my permanent home in Gibraltar. The information given on this form is true to the best of my knowledge and belief. I understand that it is a criminal offence to give false information and that I may be prosecuted and fined £1,000, or sent to prison for six months, or both, if I include, or cause to be included, information which I know is false or do not believe to be true. I also understand that the Civil Status and Registration Office holds and uses data in accordance with the Data Protection Act 2004. -

Tmgm1de3.Pdf

Melissa G. Moyer ANALYSIS OF CODE-SWITCHING IN GIBRALTAR Tesi doctoral dirigida per la Dra. Aránzazu Usandizaga Departament de Filologia Anglesa i de Germanística Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona 1992 To Jesús, Carol, and Robert ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The ¡dea of studying Gibraltar was first suggested to me by José Manuel Blecua in 1987 when I returned from completing a master's degree in Linguistics at Stanford University. The summer of that year I went back to California and after extensive library searches on language and Gibraltar, I discovered that little was known about the linguistic situation on "The Rock". The topic at that point had turned into a challenge for me. I immediately became impatient to find out whether it was really true that Gibraltarians spoke "a funny kind of English" with an Andalusian accent. It was José Manuel Blecua's excellent foresight and his helpful guidance throughout all stages of the fieldwork, writing, and revision that has made this dissertation possible. Another person without whom this dissertation would not have been completed is Aránzazu (Arancha) Usandizaga. As the official director she has pressured me when I've needed pressure, but she has also known when to adopt the role of a patient adviser. Her support and encouragement are much appreciated. I am also grateful to the English Department at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona chaired by Aránzazu Usandizaga and Andrew Monnickendam who granted me several short leaves from my teaching obligations in order to carry out the fieldwork on which this research is based. The rest of the English Department gang has provided support and shown their concern at all stages. -

The Sovereignty of the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories in the Brexit Era

Island Studies Journal, 15(1), 2020, 151-168 The sovereignty of the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories in the Brexit era Maria Mut Bosque School of Law, Universitat Internacional de Catalunya, Spain MINECO DER 2017-86138, Ministry of Economic Affairs & Digital Transformation, Spain Institute of Commonwealth Studies, University of London, UK [email protected] (corresponding author) Abstract: This paper focuses on an analysis of the sovereignty of two territorial entities that have unique relations with the United Kingdom: the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories (BOTs). Each of these entities includes very different territories, with different legal statuses and varying forms of self-administration and constitutional linkages with the UK. However, they also share similarities and challenges that enable an analysis of these territories as a complete set. The incomplete sovereignty of the Crown Dependencies and BOTs has entailed that all these territories (except Gibraltar) have not been allowed to participate in the 2016 Brexit referendum or in the withdrawal negotiations with the EU. Moreover, it is reasonable to assume that Brexit is not an exceptional situation. In the future there will be more and more relevant international issues for these territories which will remain outside of their direct control, but will have a direct impact on them. Thus, if no adjustments are made to their statuses, these territories will have to keep trusting that the UK will be able to represent their interests at the same level as its own interests. Keywords: Brexit, British Overseas Territories (BOTs), constitutional status, Crown Dependencies, sovereignty https://doi.org/10.24043/isj.114 • Received June 2019, accepted March 2020 © 2020—Institute of Island Studies, University of Prince Edward Island, Canada. -

Excursion from Puerto Banús to Gibraltar by Jet

EXCURSION FROM PUERTO BANÚS TO GIBRALTAR BY JET SKI EXCURSION FROM PUERTO BANÚS TO GIBRALTAR Marbella Jet Center is pleased to present you an exciting excursion to discover Gibraltar. We propose a guided historical tour on a jet ski, along the historic and picturesque coast of Gibraltar, aimed at any jet ski lover interested in visiting Gibraltar. ENVIRONMENT Those who love jet skis who want to get away from the traffic or prefer an educational and stimulating experience can now enjoy a guided tour of the Gibraltar Coast, as is common in many Caribbean destinations. Historic, unspoiled and unadorned, what better way to see Gibraltar's mighty coastline than on a jet ski. YOUR EXPERIENCE When you arrive in Gibraltar, you will be taken to a meeting point in “Marina Bay” and after that you will be accompanied to the area where a briefing will take place in which you will be explained the safety rules to follow. GIBRALTAR Start & Finish at Marina Bay Snorkelling Rosia Bay Governor’s Beach & Gorham’s Cave Light House & Southern Defenses GIBRALTAR HISTORICAL PLACES DURING THE 2-HOUR TOUR BY JET SKI GIBRALTAR HISTORICAL PLACES DURING THE 2-HOUR TOUR BY JET SKI After the safety brief: Later peoples, notably the Moors and the Spanish, also established settlements on Bay of Gibraltar the shoreline during the Middle Ages and early modern period, including the Heading out to the center of the bay, tourists may have a chance to heavily fortified and highly strategic port at Gibraltar, which fell to England in spot the local pods of dolphins; they can also have a group photograph 1704. -

An Overlooked Colonial English of Europe: the Case of Gibraltar

.............................................................................................................................................................................................................WORK IN PROGESS WORK IN PROGRESS TOMASZ PACIORKOWSKI DOI: 10.15290/CR.2018.23.4.05 Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań An Overlooked Colonial English of Europe: the Case of Gibraltar Abstract. Gibraltar, popularly known as “The Rock”, has been a British overseas territory since the Treaty of Utrecht was signed in 1713. The demographics of this unique colony reflect its turbulent past, with most of the population being of Spanish, Portuguese or Italian origin (Garcia 1994). Additionally, there are prominent minorities of Indians, Maltese, Moroccans and Jews, who have also continued to influence both the culture and the languages spoken in Gibraltar (Kellermann 2001). Despite its status as the only English overseas territory in continental Europe, Gibraltar has so far remained relatively neglected by scholars of sociolinguistics, new dialect formation, and World Englishes. The paper provides a summary of the current state of sociolinguistic research in Gibraltar, focusing on such aspects as identity formation, code-switching, language awareness, language attitudes, and norms. It also delineates a plan for further research on code-switching and national identity following the 2016 Brexit referendum. Keywords: Gibraltar, code-switching, sociolinguistics, New Englishes, dialect formation, Brexit. 1. Introduction Gibraltar is located on the southern tip of the Iberian Peninsula and measures just about 6 square kilometres. This small size, however, belies an extraordinarily complex political history and social fabric. In the Brexit referendum of 23rd of June 2016, the inhabitants of Gibraltar overwhelmingly expressed their willingness to continue belonging to the European Union, yet at the moment it appears that they will be forced to follow the decision of the British govern- ment and leave the EU (Garcia 2016). -

Gibraltar's Constitutional Future

RESEARCH PAPER 02/37 Gibraltar’s Constitutional 22 MAY 2002 Future “Our aims remain to agree proposals covering all outstanding issues, including those of co-operation and sovereignty. The guiding principle of those proposals is to build a secure, stable and prosperous future for Gibraltar and a modern sustainable status consistent with British and Spanish membership of the European Union and NATO. The proposals will rest on four important pillars: safeguarding Gibraltar's way of life; measures of practical co-operation underpinned by economic assistance to secure normalisation of relations with Spain and the EU; extended self-government; and sovereignty”. Peter Hain, HC Deb, 31 January 2002, c.137WH. In July 2001 the British and Spanish Governments embarked on a new round of negotiations under the auspices of the Brussels Process to resolve the sovereignty dispute over Gibraltar. They aim to reach agreement on all unresolved issues by the summer of 2002. The results will be put to a referendum in Gibraltar. The Government of Gibraltar has objected to the process and has rejected any arrangement involving shared sovereignty between Britain and Spain. Gibraltar is pressing for the right of self-determination with regard to its constitutional future. The Brussels Process covers a wide range of topics for discussion. This paper looks primarily at the sovereignty debate. It also considers how the Gibraltar issue has been dealt with at the United Nations. Vaughne Miller INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS AND DEFENCE SECTION HOUSE OF COMMONS LIBRARY Recent Library Research Papers include: List of 15 most recent RPs 02/22 Social Indicators 10.04.02 02/23 The Patents Act 1977 (Amendment) (No. -

General Assembly Distr.: General 18 March 2009

United Nations A/AC.109/2009/15 General Assembly Distr.: General 18 March 2009 Original: English Special Committee on the Situation with regard to the Implementation of the Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples Gibraltar Working paper prepared by the Secretariat Contents Page I. General ....................................................................... 3 II. Constitutional, legal and political issues ............................................ 3 III. Budget ....................................................................... 5 IV. Economic conditions ............................................................ 5 A. General................................................................... 5 B. Trade .................................................................... 6 C. Banking and financial services ............................................... 6 D. Transportation, communications and utilities .................................... 7 E. Tourism .................................................................. 8 V. Social conditions ............................................................... 8 A. Labour ................................................................... 8 B. Human rights .............................................................. 9 C. Social security and welfare .................................................. 9 D. Public health .............................................................. 9 E. Education ................................................................ -

Press Release

PRESS RELEASE No: 756/2015 Date: 21st October 2015 Gibraltar authors bring Calpean zest to Literary Festival events As the date for the Gibunco Gibraltar Literary Festival draws closer, the organisers have released more details of the local authors participating in the present edition. The confirmed names are Adolfo Canepa, Richard Garcia, Mary Chiappe & Sam Benady and Humbert Hernandez. Former AACR Chief Minister Adolfo Canepa was Sir Joshua Hassan’s right-hand man for many years. Currently Speaker and Mayor of the Gibraltar Parliament, Mr Canepa recently published his memoirs ‘Serving My Gibraltar,’ where he gives a candid account of his illustrious and extensive political career. Interestingly, Mr Canepa, who was first elected to the Rock’s House of Assembly in 1972, has held all the major public offices in Gibraltar, including that of Leader of the Opposition. Richard Garcia, a retired teacher, senior Civil Servant and former Chief Secretary, is no stranger to the Gibunco Gibraltar Literary Festival. He has written numerous books in recent years delving into the Rock's social history including the evolution of local commerce. An internationally recognised philatelist, Mr Garcia will be presenting his latest work commemorating the 50th anniversary of the event’s main sponsor, the Gibunco Group, and the Bassadone family history since 1737. Mary Chiappe, half of the successful writing tandem behind the locally flavoured detective series ‘The Bresciano Mysteries’ – the other half being Sam Benady – returns to the festival with her literary associate to delight audiences with the suggestively titled ‘The Dead Can’t Paint’, seventh and final instalment of their detective series. -

Tuesday 11Th June 2019

P R O C E E D I N G S O F T H E G I B R A L T A R P A R L I A M E N T AFTERNOON SESSION: 3.04 p.m. – 5.45 p.m. Gibraltar, Tuesday, 11th June 2019 Contents Appropriation Bill 2019 – For Second Reading – Debate continued ........................................ 2 The House adjourned at 5.45 p.m. .......................................................................................... 39 _______________________________________________________________________________ Published by © The Gibraltar Parliament, 2019 GIBRALTAR PARLIAMENT, TUESDAY, 11th JUNE 2019 The Gibraltar Parliament The Parliament met at 3.04 p.m. [MR SPEAKER: Hon. A J Canepa CMG GMH OBE in the Chair] [CLERK TO THE PARLIAMENT: P E Martinez Esq in attendance] Appropriation Bill 2019 – For Second Reading – Debate continued Mr Speaker: The Hon. Trevor Hammond. Hon. T N Hammond: Mr Speaker, I am delighted to have another opportunity to deliver a 5 Budget speech, my first in an election year. I would like to begin with the environment. This year saw this House pass unanimously a motion recognising that our planet faces a climate emergency. While there are still many people who would deny this fact, it is true to say that none sit in this House. I congratulate the Minister for showing leadership in bringing the motion and Government as a whole for seeing the 10 wisdom of accepting a minor amendment which would allow its unanimous passage. There is no doubt that all of us seated here understand the urgency of the global crisis being faced and appreciate the need for urgency and continued unanimity in mapping out our community’s future. -

Feb/March/April 2014 Volume 20/ Number 1

GIBRALTFebA/March/RApril 2014 I NTER NATIONAL F I N A N C E n I N V E S T M E N T n B U S I N E S S Race begins to dig into new office projects www.gibraltarinternational.com Sponsors Gibraltar International Magazine is grateful for the support of the finance industry and allied services (with the encouragement of the Finance Council) in the form of committed sponsorship. We would like to thank the following sponsors: GIBRALTAR FINANCE CENTRE Tel: + (350) 200 50011 • Fax: + (350) 200 51818 www.gibraltar.gov.gi DELOITTE ABACUS FINANCIAL SERVICES LIMITED Tel: + (350) 200 41200 • Fax + (350) 200 41201 Tel: + (350) 200 78777 www.deloitte.gi Fax: + (350) 200 76689 EUROPA TRUST COMPANY LIMITED www.abacus.gi Tel: + (350) 200 79013 • Fax + (350) 200 70101 QUEST INSURANCE MANAGEMENT LTD. www.europa.gi Tel: + (350) 200 74570 • Fax + (350) 200 40901 HASSANS www.quest.gi Tel: + (350) 200 79000 • Fax + (350) 200 71966 GIBTELECOM time after time www.gibraltarlaw.com Tel: + (350) 200 52200 • Fax: + (350) 200 71673 GRANT THORNTON www.gibtele.com 5SJBZBOE5SJBZXBTFTUBCMJTIFEJO Gibraltar’s Lawyers Since 1905 Tel: + (350) 200 45502 • Fax: + (350) 200 51071 KPMG BOETUJMMSFNBJOTBUUIFGPSFGSPOUPGUIFMFHBM t$PSQPSBUF$PNNFSDJBM www.grantthornton.gi Tel: + (350) 200 48600 • Fax: + (350) 200 49554 QSPGFTTJPOJO(JCSBMUBS XJUIBUSJFEBOEUSVTUFE t&NQMPZNFOU BAKER TILLY (GIBRALTAR) LTD www.kpmg.gi SFQVUBUJPOGPSFYDFMMFODFBNPOHTU t'BNJMZ Tel: + (350) 200 74015 • Fax: + (350) 200 74016 SAPPHIRE NETWORKS www.bakertillygibraltar.gi PVSDMJFOUTBOEQFFST t'JOBODJBM4FSWJDFT*OWFTUNFOU'VOET -

On Rocks and Hard Places

On Rocks And Hard Places Transforming Borders and Identities in Pre-Brexit Gibraltar Fabian Berends 4069331 Utrecht University 2nd of August 2019 A thesis submitted to the Board of Examiners in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts in Conflict Studies and Human Rights Supervisor: Dr. Ralph W.F.G. Sprenkels Date of Submission: 2nd of August 2019 Program Trajectory: Research and Thesis Writing only (30 ECTS) Word Count: 28896 Cover Photo: The Gibraltar-Spain border from the Spanish side. Source: author. Declaration of Originality/Plagiarism Declaration MA Thesis in Conflict Studies & Human Rights Utrecht University (course module GKMV 16028) I hereby declare: • that the content of this submission is entirely my own work, except for quotations from published and unpublished sources. These are clearly indicated and acknowledged as such, with a reference to their sources provided in the thesis text, and a full reference provided in the bibliography; • that the sources of all paraphrased texts, pictures, maps, or other illustrations not resulting from my own experimentation, observation, or data collection have been correctly referenced in the thesis, and in the bibliography; • that this Master of Arts thesis in Conflict Studies & Human Rights does not contain material from unreferenced external sources (including the work of other students, academic personnel, or professional agencies); • that this thesis, in whole or in part, has never been submitted elsewhere for academic credit; • that I have read and understood Utrecht University’s definition of plagiarism, as stated on the University’s information website on “Fraud and Plagiarism”: “Plagiarism is the appropriation of another author’s works, thoughts, or ideas and the representation of such as one’s own work.” (Emphasis added.)1 Similarly, the University of Cambridge defines “plagiarism” as “ … submitting as one's own work, irrespective of intent to deceive, that which derives in part or in its entirety from the work of others without due acknowledgement.