Tmgm1de3.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Application for Gibraltarian Status (Section 9)

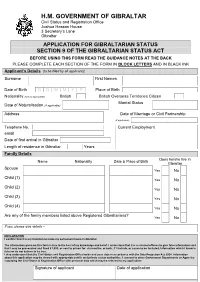

H.M. GOVERNMENT OF GIBRALTAR Civil Status and Registration Office Joshua Hassan House 3 Secretary’s Lane Gibraltar APPLICATION FOR GIBRALTARIAN STATUS SECTION 9 OF THE GIBRALTARIAN STATUS ACT BEFORE USING THIS FORM READ THE GUIDANCE NOTES AT THE BACK PLEASE COMPLETE EACH SECTION OF THE FORM IN BLOCK LETTERS AND IN BLACK INK Applicant’s Details (to be filled by all applicants) Surname First Names Date of Birth D D M M Y Y Place of Birth Nationality (tick as appropriate) British British Overseas Territories Citizen Marital Status Date of Naturalisation (if applicable) Address Date of Marriage or Civil Partnership (if applicable) Telephone No. Current Employment email Date of first arrival in Gibraltar Length of residence in Gibraltar Years Family Details Does he/she live in Name Nationality Date & Place of Birth Gibraltar Spouse Yes No Child (1) Yes No Child (2) Yes No Child (3) Yes No Child (4) Yes No Are any of the family members listed above Registered Gibraltarians? Yes No If yes, please give details – DECLARATION I confirm that it is my intention to make my permanent home in Gibraltar. The information given on this form is true to the best of my knowledge and belief. I understand that it is a criminal offence to give false information and that I may be prosecuted and fined £1,000, or sent to prison for six months, or both, if I include, or cause to be included, information which I know is false or do not believe to be true. I also understand that the Civil Status and Registration Office holds and uses data in accordance with the Data Protection Act 2004. -

The Troubadours

The Troubadours H.J. Chaytor The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Troubadours, by H.J. Chaytor This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: The Troubadours Author: H.J. Chaytor Release Date: May 27, 2004 [EBook #12456] Language: English and French Character set encoding: ASCII *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE TROUBADOURS *** Produced by Ted Garvin, Renald Levesque and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team. THE TROUBADOURS BY REV. H.J. CHAYTOR, M.A. AUTHOR OF "THE TROUBADOURS OF DANTE" ETC. Cambridge: at the University Press 1912 _With the exception of the coat of arms at the foot, the design on the title page is a reproduction of one used by the earliest known Cambridge printer, John Siberch, 1521_ PREFACE This book, it is hoped, may serve as an introduction to the literature of the Troubadours for readers who have no detailed or scientific knowledge of the subject. I have, therefore, chosen for treatment the Troubadours who are most famous or who display characteristics useful for the purpose of this book. Students who desire to pursue the subject will find further help in the works mentioned in the bibliography. The latter does not profess to be exhaustive, but I hope nothing of real importance has been omitted. H.J. CHAYTOR. THE COLLEGE, PLYMOUTH, March 1912. CONTENTS PREFACE CHAP. I. INTRODUCTORY II. -

Annual Report Childline Gibraltar 2015/2016

Childline Gibraltar Annual Report 2015 / 2016 Helpline Services: Freephone: 8008 Online: [email protected] Live-Chat via our website: www.childline.gi Office: Tel 200 43503 Email: [email protected] Website: www.childline.gi Need to talk to someone? Contact us We can help! 2 Freephone:Freephone: 8008 8008 Online: Online: [email protected] [email protected] Live-chat Live-Chat via via our our website: website: www.childline.gi www.childline.gi Contents Message from the Chairperson .......................4 A Brief History of Childline Gibraltar .............5 1) Summary of Major Achievements in 2015/2016 .......................................................6 2) Administrative Information ...........................7 3) Our Mission, Vision and Values ...................8 4) Childline Gibraltar - Core Services ............8 5) Helpline Statistics .................................................8 6) The Appropriate Adult Service................ 13 7) Education Service ............................................. 15 8) Fund-raising Report ........................................ 18 9) Visit from Dame Esther Rantzen ............ 19 10) 10th Anniversary Ball ..................................... 20 11) Marketing and Social Media ..................... 21 12) Financial .................................................................. 22 13) Operational Aims for 2016/2017 ........... 22 Acknowledgements ................................................. 23 Freephone: 8008 Online: [email protected] Live-chat via our website: www.childline.gi -

On the Source of the Infinitive in Romance-Derived Pidgins and Creoles

On the source of the infinitive in Romance-derived pidgins and creoles John M. Lipski The Pennsylvania State University Introduction A recent comic strip, resuscitating racial stereotypes which had purportedly disappeared at least a century ago, depicted a dialogue between a Spanish priest and an outrageous parody of an African `native.' The latter begins by addressing the priest as follows: Yo estar muy enojado. Yo haber tenido 10 hijos, "todos de color"! Ahora el 11vo. nacer blanco! Ud. ser el único hombre blanco en 200 km. Ud. deber "EXPLICARME." [I am very angry. I've had ten children, "all colored!" Now the 11th one has been born white! You are the only white man within 200 km. You must "explain to me."] This stereotype is confirmed by independent observations. Ferguson (1971: 143-4) says that `a speaker of Spanish who wishes to communicate with a foreigner who has little or no Spanish will typically use the infinitive of the verb or the third singular rather than the usual inflected forms, and he will use mi `my' for yo `I' and omit the definite and indefinite articles: mi ver soldado `me [to-] see soldier' for yo veo al soldado `I see the soldier.' Such Spanish is felt by native speakers of the language to be the way foreigners talk, and it can most readily be elicited from Spanish-speaking informants by asking them how foreigners speak.' Thompson (1991) presented native speakers of Spanish with options as how to address a newly-hired employee who spoke little Spanish. A large number of respondents preferred sentences with bare -

Annual Report 2018

Annual Report 2018 Table of Contents Page No 1 OMBUDSMAN’S INTRODUCTION 3 2 HIGHLIGHTS FOR 2018 7 2.1 Recommendations in previous Annual Reports 9 2.2 Review of Health Complaints Procedure 16 2.3 Issues highlighted in investigations carried out by the Ombudsman in 2018 17 2.4 Government Policy – v – Administrative Action 23 3 THE OMBUDSMAN’S ROLE AND FUNCTION 25 3.1 The Ombudsman’s Role and Function 27 3.2 Ombudsman’s Strategic Objectives 33 3.3 Principles for Remedy 36 4 DIARY OF EVENTS 2018 41 5 PERFORMANCE REVIEW 2018 47 6 20 YEAR JOURNEY OF THE OMBUDSMAN 55 7 APPENDIXES 83 7.1 Delegation of duties and decision-making authority by the Ombudsman 85 7.2 Principles of Good Governance and Mission Statement 87 7.3 Financial Statements 88 7.4 Complaints about the service provided by the Ombudsman’s Office 89 7.5 Public Service Ombudsman - Flow Chart on Handling of Investigations 92 8 OMBUDSMAN’S CASEBOOK 93 1 2 Ombudsman’s Introduction This year marks the 20th Anniversary of the establishment of the Public Services Ombudsman’s Office in Gibraltar. This is the Public Services Ombudsman’s 19th Annual Report. 3 4 Ombudsman’s Introduction This year marks the 20th Anniversary of the establishment of the Public Services Ombudsman’s Office in Gibraltar. This is the Public Services Ombudsman’s 19th Annual Report. The work of the Ombudsman’s Office has developed significantly over the past 20 years. The Office is now firmly established as an institution that provides an important check on Government Departments and other Public Service Providers. -

Italian-Spanish Contact in Early 20Th Century Argentina

Ennis, Juan Antonio Italian-Spanish Contact in Early 20th Century Argentina Journal of language contact 2015, vol. 8, nro. 1, p. 112-145 Ennis, J. (2015). Italian-Spanish Contact in Early 20th Century Argentina. Journal of language contact, 8 (1), 112-145. En Memoria Académica. Disponible en: http://www.memoria.fahce.unlp.edu.ar/art_revistas/pr.9987/pr.9987.pdf Información adicional en www.memoria.fahce.unlp.edu.ar Esta obra está bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial 4.0 Internacional https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ journal of language contact 8 (2015) 112-145 brill.com/jlc Italian-Spanish Contact in Early 20th Century Argentina Juan Antonio Ennis conicet/Universidad de La Plata [email protected] Abstract This article attempts to provide a general approach to the exceptional language contact situation that took place in Argentina from the end of the 19th century until the first decades of the 20th century, in which an enormous immigration flow drastically modified the sociolinguistic landscape. This was most evident in urban environments—and among them especially the Buenos Aires area—and led the local ruling elites to set up a complex and massive apparatus for the nationalisation of the newcomers, which included a language shift in the first stage. Given that the majority of immigrants came from Italy, the most widespread form of contact was that between the local varieties of Spanish and the Italian dialects spoken by the immigrants, which led to the creation of a contact variety called Cocoliche that arose, lived then perished. Although this contact variety did not survive the early years, at least not as a full- fledged variety, the history of its emergence and the ways in which it can be studied today nevertheless make it an object of special interest for research perspectives ori- ented around the question of the early years of language contact. -

General Assembly Distr.: General 7 March 2017

United Nations A/AC.109/2017/8 General Assembly Distr.: General 7 March 2017 Original: English Special Committee on the Situation with regard to the Implementation of the Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples Gibraltar Working paper prepared by the Secretariat Contents Page I. General ....................................................................... 3 II. Constitutional, legal and political issues ............................................ 3 III. Budget ....................................................................... 5 IV. Economic conditions ............................................................ 5 A. General ................................................................... 5 B. Trade .................................................................... 6 C. Banking and financial services ............................................... 6 D. Transportation ............................................................. 7 E. Tourism .................................................................. 8 V. Social conditions ............................................................... 8 A. Labour ................................................................... 8 B. Social security and welfare .................................................. 9 Note: The information contained in the present working paper has been derived from information transmitted to the Secretary-General by the administering Power under Article 73 e of the Charter of the United Nations as well as information -

As Andalusia

THE SPANISH OF ANDALUSIA Perhaps no other dialect zone of Spain has received as much attention--from scholars and in the popular press--as Andalusia. The pronunciation of Andalusian Spanish is so unmistakable as to constitute the most widely-employed dialect stereotype in literature and popular culture. Historical linguists debate the reasons for the drastic differences between Andalusian and Castilian varieties, variously attributing the dialect differentiation to Arab/Mozarab influence, repopulation from northwestern Spain, and linguistic drift. Nearly all theories of the formation of Latin American Spanish stress the heavy Andalusian contribution, most noticeable in the phonetics of Caribbean and coastal (northwestern) South American dialects, but found in more attenuated fashion throughout the Americas. The distinctive Andalusian subculture, at once joyful and mournful, but always proud of its heritage, has done much to promote the notion of andalucismo within Spain. The most extreme position is that andaluz is a regional Ibero- Romance language, similar to Leonese, Aragonese, Galician, or Catalan. Objectively, there is little to recommend this stance, since for all intents and purposes Andalusian is a phonetic accent superimposed on a pan-Castilian grammatical base, with only the expected amount of regional lexical differences. There is not a single grammatical feature (e.g. verb cojugation, use of preposition, syntactic pattern) which separates Andalusian from Castilian. At the vernacular level, Andalusian Spanish contains most of the features of castellano vulgar. The full reality of Andalusian Spanish is, inevitably, much greater than the sum of its parts, and regardless of the indisputable genealogical ties between andaluz and castellano, Andalusian speech deserves study as one of the most striking forms of Peninsular Spanish expression. -

For a Mapping of the Languages/Dialects of Italy And

For a mapping of the languages/dialects of Italy and regional varieties of Italian Philippe Boula de Mareüil, Eric Bilinski, Frédéric Vernier, Valentina de Iacovo, Antonio Romano To cite this version: Philippe Boula de Mareüil, Eric Bilinski, Frédéric Vernier, Valentina de Iacovo, Antonio Romano. For a mapping of the languages/dialects of Italy and regional varieties of Italian. New Ways of Analyzing Dialectal Variation, In press. hal-03318939 HAL Id: hal-03318939 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03318939 Submitted on 11 Aug 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. For a mapping of the languages/dialects of Italy and regional varieties of Italian Introduction Unifi ed late, Italy is well-known for its great linguistic diversity. This diversity has been thoroughly covered by linguistic atlases such as the Italian-Swiss Atlas (Jaberg / Jud 1928-1940), the Italian Linguistic Atlas (Bartoli et al. 1995), or the linguistic atlases of the Dolomites (Goebl 2003, 2012), Sicily (Sottile 2018), Calabria (Krefeld 2019) and the Piedmont mountains (Cugno / Cusan 2019), for which projects have undertaken to digitise a portion of the material (Tisato 2010) 1 . In other countries, too, various projects have aimed to make the dialect data collected in the 20th century more widely accessible: in France (Goebl 2002; Oliviéri et al. -

Italian Sociolinguistics, Department of Modern Languages, University of Reading – Supporteditalians by the Faculty of Arts & Humanities Teaching & Learning Office

Reading Newsletter written & edited by the students of Italian Sociolinguistics, Department of Modern Languages, University of Reading – SupportedItalians by the Faculty of Arts & Humanities Teaching & Learning Office Code-mixing and code-switching in a multilingual family What are people’s attitutes towards Genoese dialect? I giovani ravennati e il dialetto romagnolo Il linguaggio di Clelia Marchi English as L2 for Italian Erasmus students at Reading Code-Switching and code-Mixing in my bilingual family Do young Catanese people still use dialect? You are what you eat, but do you know what you are eating? A message from the editors When we edited the first issue of Reading Italians we thought that introducing the research What are people’s attitutes Key words you may projects we were working on for our Sociolinguistics module (IT3SOCLING) would be a towards Genoese dialect? need to know... good way of gathering our (first) ideas about a topic that was still relatively new to all of us. (by the editorial board) The possibility of presenting this just from friends have encouraged us to pics – has now found its body and shape. After spending my year abroad in Genoa, I got very interested in the local dialect, the “Genovese”. In order to know more about it, and particularly about “intruduction” through a totally new work on this second issue. The general tone of the our writing Code mixing student-led “newsletter” was very exci- As you will see, this issue is very similar is – to some extent – more “serious” than its use, I have prepared a socio-linguistic survey based on a questionnaire addressed It involves the transfer of lingui- ting. -

Gibraltar Constitution Order 2006

At the Court at Buckingham Palace THE 14th DAY OF DECEMBER 2006 PRESENT, THE QUEEN’S MOST EXCELLENT MAJESTY IN COUNCIL Whereas Gibraltar is part of Her Majesty’s dominions and Her Majesty’s Government have given assurances to the people of Gibraltar that Gibraltar will remain part of Her Majesty’s dominions unless and until an Act of Parliament otherwise provides, and furthermore that Her Majesty’s Government will never enter into arrangements under which the people of Gibraltar would pass under the sovereignty of another state against their freely and democratically expressed wishes: And whereas the people of Gibraltar have in a referendum held on 30th November 2006 freely approved and accepted the Constitution annexed to this Order which gives the people of Gibraltar that degree of self-government which is compatible with British sovereignty of Gibraltar and with the fact that the United Kingdom remains fully responsible for Gibraltar’s external relations: Now, therefore, Her Majesty, by virtue and in exercise of all the powers enabling Her to do so, is pleased, by and with the advice of Her Privy Council, to order, and it is ordered, as follows:- Citation, commencement and interpretation 1.-(1) This Order may be cited as the Gibraltar Constitution Order 2006. (2) This Order shall be published in the Gazette and shall come into force on the day it is so published. (3) In this Order – “the appointed day” means such day as may be prescribed by the Governor by proclamation in the Gazette; “the Constitution” means the Constitution set out in Annex 1 to this Order; 1 “the existing Order” means the Gibraltar Constitution Order 1969(a). -

Tuesday 11Th June 2019

P R O C E E D I N G S O F T H E G I B R A L T A R P A R L I A M E N T MORNING SESSION: 10.01 a.m. – 12.47 p.m. Gibraltar, Tuesday, 11th June 2019 Contents Appropriation Bill 2019 – For Second Reading – Debate continued ........................................ 2 The House adjourned at 12.47 p.m. ........................................................................................ 36 _______________________________________________________________________________ Published by © The Gibraltar Parliament, 2019 GIBRALTAR PARLIAMENT, TUESDAY, 11th JUNE 2019 The Gibraltar Parliament The Parliament met at 10.01 a.m. [MR SPEAKER: Hon. A J Canepa CMG, GMH, OBE, in the Chair] [CLERK TO THE PARLIAMENT: P E Martinez Esq in attendance] Appropriation Bill 2019 – For Second Reading – Debate continued Clerk: Tuesday, 11th June 2019 – Meeting of Parliament. Bills for First and Second Reading. We remain on the Second Reading of the Appropriation 5 Bill 2019. Mr Speaker: The Hon. Dr John Cortes. Minister for the Environment, Energy, Climate Change and Education (Hon. Dr J E Cortes): Good morning, Mr Speaker. I rise for my eighth Budget speech conscious that being the last one in the electoral cycle it could conceivably be my last. While resisting the temptation to summarise the accomplishments of this latest part of my life’s journey, I must however comment very briefly on how different Gibraltar is today from an environmental perspective. In 2011, all you could recycle here was glass. There was virtually no climate change awareness, no possibility of a Parliament even debating let alone passing a motion on the climate emergency.