Celtic Coins from the Romano-British Temple at Harlow

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Welsh Classical Dictionary

A WELSH CLASSICAL DICTIONARY DACHUN, saint of Bodmin. See s.n. Credan. He has been wrongly identified with an Irish saint Dagan in LBS II.281, 285. G.H.Doble seems to have been misled in the same way (The Saints of Cornwall, IV. 156). DAGAN or DANOG, abbot of Llancarfan. He appears as Danoc in one of the ‘Llancarfan Charters’ appended to the Life of St.Cadog (§62 in VSB p.130). Here he is a clerical witness with Sulien (presumably abbot) and king Morgan [ab Athrwys]. He appears as abbot of Llancarfan in five charters in the Book of Llandaf, where he is called Danoc abbas Carbani Uallis (BLD 179c), and Dagan(us) abbas Carbani Uallis (BLD 158, 175, 186b, 195). In these five charters he is contemporary with bishop Berthwyn and Ithel ap Morgan, king of Glywysing. He succeeded Sulien as abbot and was succeeded by Paul. See Trans.Cym., 1948 pp.291-2, (but ignore the dates), and compare Wendy Davies, LlCh p.55 where Danog and Dagan are distinguished. Wendy Davies dates the BLD charters c.A.D.722 to 740 (ibid., pp.102 - 114). DALLDAF ail CUNIN COF. (Legendary). He is included in the tale of ‘Culhwch and Olwen’ as one of the warriors of Arthur's Court: Dalldaf eil Kimin Cof (WM 460, RM 106). In a triad (TYP no.73) he is called Dalldaf eil Cunyn Cof, one of the ‘Three Peers’ of Arthur's Court. In another triad (TYP no.41) we are told that Fferlas (Grey Fetlock), the horse of Dalldaf eil Cunin Cof, was one of the ‘Three Lovers' Horses’ (or perhaps ‘Beloved Horses’). -

Series Summary Index Vols

SERIES SUMMARY INDEX VOLS. XXXI-XL (1962-1971) R. H. THOMPSON Abbreviations: c. century; exh. exhibited, exhibition(s) (by); i.m. initial mark: obit. obituary (of): obv. obverse; pl(s). plate(s); rev. review of, reviewed, reverse. Omissions: Accounts, elections within the Society, and other regular features (dates of election being given in each List of Members); subject entries for most reviews. Deaths, exhibitions, readers and their subjects, reviews, are entered under their individual head- ings, as also are finds, with references from Finds . according to the series and date of the material. References to places in the British Isles are collected by county. Aberdeen, mint (James III), XL. 82-4, pi. v /Ethelred II, Last Small Cross type, obv. pointed Aberdeenshire, see also Birse parish helmet, xxxix. 201, 204, pi. ix Aberystwyth, mint (Charles I, unites), see Chester — Long Cross type, see also Lincoln, London, Stam- Addedomaros (Trinovantes), see also British Lx ford, mints — staters, xxxvir. 190, pi. xxi subsidiary issue, xxxiv. 37-41, pis. ii-iii; exh., Advertising (Imitation spade guineas), see Imitation 189; read, 188 spade guineas, advertisements — types, chronology, xxxv. 37; xxxix. 200 Alfred, see Alfred /Ethelred (Canterbury), coinage, xxxi. 43-4, pi. iii; /Ethelbald, coins, see Forgery exh., 173 /Ethelred I, coins, exh., xxxvu. 215 /Ethelstan, see Athelstan — type i, lunettes unbroken, moneyer Ethelred, /Ethelwald Moll (Northumbria), coin, xxxvi. 216 xxxvi. 33-4 /Ethelwulf, coinage, xxxn. 19; xxxvii. 226-7; exh., /Ethelred II, see also Chester, Northampton, South- 215 ampton, mints; Southampton/Winchester die- /Ethered (Canterbury), see /Ethelred linking Alderwasley (Derbys.), find 1971 (16-17 c.), XL. -

Celtic Britain

1 arfg Fitam ©0 © © © © ©©© © © © © © © 00 « G XT © 8 i imiL ii II I IWtv,-.,, iM » © © © © © ©H HWIW© llk< © © J.Rhjsffi..H. © I EARLY BRITAIN, CELTIC BRITAIN. BY J. RHYS, M.A., D.Litt. (Oxon/). Honorary LL.D. (Edin.). Honorary D.Litt. (Wales). FROFESSOR OF CELTIC IN THE UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD J PRINCIPAL OF JESUS COLLEGE, AND LATE FELLOW OF MERTON COLLEGE FELLOW OF THE BRITISH ACADEMY. WITH TWO MAPS, AND WOODCUTS OF COIliS, FOURTH EDITION. FUBLISHED UNDER THE D.RECTION OF THE GENERAL LITERATURE COMMITTEE. LONDON: SOCIETY FOR PROMOTING CHRISTIAN KNOWLEDGE, NORTHUMBERLAND AVENUE, W.C. ; 43, queen victoria street, e.c. \ Brighton: 129, north street. New York : EDWIN S. GORHAM. iqoP, HA 1^0 I "l C>9 |X)VE AND MALCOMSON, LIMITED, PRINTERS, 4 AND 5, DEAN STREET, HIGH HOLBORN, LONDON, W.C. PREFACE TO THE FIRST EDITION. These are the days of little books, and when the author was asked to add one to their number, he accepted the invitation with the jaunty simplicity of an inexperienced hand, thinking that it could not give him much trouble to expand or otherwise modify the account given of early Britain in larger works ; but closer acquaintance with them soon convinced him of the folly of such a plan— he had to study the subject for himself or leave it alone. In trying to do the former he probably read enough to have enabled him to write a larger work than this ; but he would be ashamed to confess how long it has occupied him. As a student of language, he is well aware that no severer judgment could be passed on his essay in writing history than that it should be found to be as bad as the etymologies made by historians are wont to be ; but so essential is the study of Celtic names to the elucidation of the early history of Britain that the risk is thought worth incurring. -

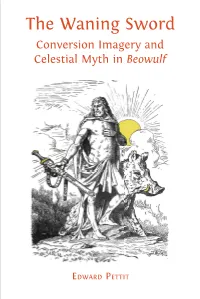

The Waning Sword E Conversion Imagery and Celestial Myth in Beowulf DWARD the Waning Sword Conversion Imagery and EDWARD PETTIT P

The Waning Sword E Conversion Imagery and Celestial Myth in Beowulf DWARD The Waning Sword Conversion Imagery and EDWARD PETTIT P The image of a giant sword mel� ng stands at the structural and thema� c heart of the Old ETTIT Celestial Myth in Beowulf English heroic poem Beowulf. This me� culously researched book inves� gates the nature and signifi cance of this golden-hilted weapon and its likely rela� ves within Beowulf and beyond, drawing on the fi elds of Old English and Old Norse language and literature, liturgy, archaeology, astronomy, folklore and compara� ve mythology. In Part I, Pe� t explores the complex of connota� ons surrounding this image (from icicles to candles and crosses) by examining a range of medieval sources, and argues that the giant sword may func� on as a visual mo� f in which pre-Chris� an Germanic concepts and prominent Chris� an symbols coalesce. In Part II, Pe� t inves� gates the broader Germanic background to this image, especially in rela� on to the god Ing/Yngvi-Freyr, and explores the capacity of myths to recur and endure across � me. Drawing on an eclec� c range of narra� ve and linguis� c evidence from Northern European texts, and on archaeological discoveries, Pe� t suggests that the T image of the giant sword, and the characters and events associated with it, may refl ect HE an elemental struggle between the sun and the moon, ar� culated through an underlying W myth about the the� and repossession of sunlight. ANING The Waning Sword: Conversion Imagery and Celesti al Myth in Beowulf is a welcome contribu� on to the overlapping fi elds of Beowulf-scholarship, Old Norse-Icelandic literature and Germanic philology. -

Boomershine Major Players BEFORE 1500

THE REUBEN BOOMERSHINE FAMILY STORY (Some Characters Before 1500) Reynold of CHATILLON-SUR-LOING Birth: 1090/1137 Death: 1187, executed on orders of Saladin after the battle of Hattin Alexander "1st Lord of Boketon" De Boketon: Event: Note As far as ALEXANDER DE BOKETON's ancestors, this was rec'd from LDS, so, they are NOT proven. Event: Note His great grandfather was one of the Norman nobles who invaded England with William the Conqueror. Burial: ABT. 1236 St. John the Baptist Cemetery, Greenes Norton, County Northampshire, ENGLAND Immigration: BET. 1181 - 1202 Removed from the mainland in France to the British Isles (England) Event: Title (Facts Pg) BET. 1202 - 1236 Lord, Sir, Knight (by King John), 1st Baron de Boketon Event: Born 2 ABT. 1181 Boketon, County Northampton, ENGLAND 1 2 3 Religion: Roman Catholic Residence: 1202 King John bestowed estate of Boughton in County Northampton (England) NATI: Norman descendant Note: NOTE: The 'Holy Roman Empire', in general usage, the designation applied to an amorphour political entity of western Europe, originated by Pope Leo III in 800 A.D., and in nominal existence more or less continuously until 1806. For purposes of historical accuracy, it should be noted that, in its initial stages, the organization was styled 'Empire of the West' and 'Roman Empire'; and that the epithet "Holy" did not appear in the official title until 1155. Just an interesting bit of history, apparently our ALEXANDER DE BOKETON b:c 1181 was born under the 'Hohenstaufen Dynasty' with first emperor Frederick I reigning at his birth (c1152-1190, crowned 1155), then emperor Henry VI (1190-1197, crowned 1191). -

Churchill Enjoys Finest Hour in the Saleroom

To print, your print settings should be ‘fit to page size’ or ‘fit to printable area’ or similar. Problems? See our guide: https://atg.news/2zaGmwp 7 1 -2 0 2 1 9 1 ISSUE 2483 | antiquestradegazette.com | 13 March 2021 | UK £4.99 | USA $7.95 | Europe €5.50 S E E R 50years D koopman rare art V A I R N T antiques trade G T H E KOOPMAN (see Client Templates for issue versions) THE ART M ARKET WEEKLY [email protected] +44 (0)20 7242 7624 www.koopman.art Churchill enjoys finest hour in the saleroom Sir Winston Churchill’s (1874-1965) painting Churchill completed during ever more towering presence in the art the Second World War. Tower of the market was on full display last week as Koutoubia Mosque was painted following his auction record was broken four-and- the Casablanca Conference in January a-half times over. 1943. The British prime minister gave it Christie’s evening sale of Modern to US President Franklin D Roosevelt ‘as British art on March 1 offered the only a memento of this short interlude in the crash of war’. Having remained with Roosevelt’s Left: Tower of the Koutoubia son Elliot until 1950 and changed hands Mosque by Sir Winston Churchill – a record £7m at Christie’s. Continued on page 8 Consultation launched for Fairs make welcome Portobello’s five-year plan return to calendar the views of traders, retailers, consultation document. It Fair organisers are now From Monday, April 12, the by Laura Chesters residents and visitors. -

Who Was Caratacus? How a New Discovery Helps to Resolve an Old Controversy

Insight CHRIS RUDD Who Was CarataCus? How a new discovery helps to resolve an old controversy or over 400 years people have been trying to attribute coins to Caratacus—some rightly, others wrongly. In 1581 the antiquarian historian William Camden illustrated a gold stater of Epaticcus (ABC 1343) in his monumental Britannia, misread the legend as CEArITIC and said it was “a coine of that warlike prince, Caratacus”. Another antiquarian, Freverend William Stukeley (1687–1765), copied Camden’s drawing of the Epaticcus stater onto his own plates, but changed the inscription to CArATIC, which better suited Stukeley’s equally mistaken attribution to CArATICVS, as he called the prince. In 1846 a numismatist who should have known better, reverend Beale Poste, republished Stukeley’s stupid error in The coins of Cunobeline and of the ancient Britons. Worse was to follow. In 1862 Poste published engravings of two silver units of Epaticcus (both ABC 1346), misread both inscriptions as KErATI (supposedly a mixture of Greek and Latin letters), declared both coins to be of “Caractacus” and accused his critics of “the grossest misrepresentations”. Three years later John Evans, the father of Ancient British numismatics, delightfully debunked these early attempts to donate the gold and silver coins of Epaticcus to his nephew Caratacus. In his seminal book The coins of the Ancient Britons (1864) Evans said Poste and others “sinned against light” because cartographer John Speed (1542–1629) had previously published a virtually correct reading of the Epaticcus stater legend. He added: “When any coins of Caratacus are discovered, if such an event ever takes place, we may, at all events, expect to find that Roman letters will have been used upon them, as they always are, without exception, on the coins of his father, Cunobeline, and his grandfather, Tasciovanus.” Little did Evans know that some years later he would acquire a silver coin inscribed CARA, probably found near Guildford, Surrey, now in the British Museum (Hobbs BMC 2378, ABC 1376). -

Traduction De Joseph Loth

Notes du mont Royal www.notesdumontroyal.com 쐰 Cette œuvre est hébergée sur « No- tes du mont Royal » dans le cadre d’un exposé gratuit sur la littérature. SOURCE DES IMAGES Canadiana COURS DE LITTÉRATURE CELTIQUE ..--------- 1V OUVRAGES DE M. H. D’ARBOIS DE JUBAINVILLE EN VENTE Chez THORIN, libraire-éditeur, 7, rue de Médicis, Paris HISTOIRE DES DUCS ET DES COMTES DE CHAMPAGNE, six tomes en sept volumes in-8° (1859-1867). couns DE LITTÉRATURE manquait. I à III, in-8° (1883-1889). Prix de chaque volume : 8 fr. Les tomes IV et V sont sous presse. ESSAI DIUN CATALOGUE DE LA LITTÉRATURE ÉPIQUE DE L’IRLANDE , précédé d’une étude sur les manuscrits en langue irlandaise conservés dans les fies-Britanniques et sur le continent, ina8°, INVENTAIRE SOMMAIRE DES ARCHIVES DE LA VILLE DE BAR’SUR- RÉSUMÉSEINE.1884. D’UN COURS DE1864, DROIT IRLANDAIS, in-4°.12 professé au lcollège »5 de» France pendant le premier semestre de l’année 1887-1888, LES PREMIERS HABITANTS DE L’EUROPE, d’après les auteurs de l’an- tiquitébrochure et les recherches des linguistes. in-8°. SECONDE ÉDITIONI. 50 , cor- rigée et considérablement augmentée par l’auteur, avec la col v laboration de G. Bottin, secrétaire de la rédaction de la Revue celtique, 2 beaux vol. grand in-8° raisin. En vente : TOME I", contenant : 1° Peuples étrangers à la race l’aria-européenne (habitants des cavernes, Ibères, Pélasges, Etrus- ques, Phéniciens); - 2° Inde-EurOpe’ens , Ir0 partie (Scythes, Thraces, Illyriens, Ligures). --- Prix de ce volume : 10 » CATALOGUE D’ACTES DES COMTES DE BRIENNE, in-8°, 1872. -

On the Reading of the Coins of Cunobelin

Archaeological Journal ISSN: 0066-5983 (Print) 2373-2288 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/raij20 On the Reading of the Coins of Cunobelin Samuel Birch To cite this article: Samuel Birch (1847) On the Reading of the Coins of Cunobelin, Archaeological Journal, 4:1, 28-36, DOI: 10.1080/00665983.1847.10850647 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00665983.1847.10850647 Published online: 06 Dec 2014. Submit your article to this journal View related articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=raij20 Download by: [University of California, San Diego] Date: 29 June 2016, At: 14:08 ON THE READING OF THE COINS OF CUNOBELIN. 36 No 1. No. 2. COINS OP CUNOBELIN, FOUND AT CHESTERFORD. WHEN upon a former occasion an inspection of the coins of Cunobelin had led me to enunciate a theory relative to the meaning of the obscure word Tascio or Tasciovani, upon the reverse, I was not insensible that the novel idea suggested by the reading of these legends would be a subject for discus- sion. The newly discovered coins represented above, found at Chesterford, and now in the possession of the Hon. Richard Neville, who has kindly communicated them to the Archae- ological Institute, however, settle the question, and support in a gratifying and unexpected manner the conjecture upon which Mr. Wigan's specimen, owing to the indifferent preser- vation of the last letters, threw a slight doubt: the most scep- tical cannot now fail to be convinced that TASC. -

It Is to Be Regretted That of the Remains of Verulamium, Probably the Largest and the Most Important Roman City in England

0 49 Notes on the Remains of Verulamium. BY W. PAGE, FSQ., F.S.A. It is to be regretted that of the remains of Verulamium, probably the largest and the most important Roman city in England, and one of the only two in Britain that were honoured with the title of municipium, comparatively little is known. Caleva or Silchester is now being excavated with most important archaeological and his- torical results such as the finding of the Christian Church there. Uriconium or Wroxeter in Shropshire has been explored, and of London, Colchester, York, Carlisle, and Bath a considerable amount is known, and so with many other less important Roman towns. Wherever a site of a Roman settlement exists the earth has always preserved to us some footprints of that mighty empire. Of course, with our knowledge of other Roman towns, much can be guessed at as to Verulamium, but how much more valu- able would it be to make the earth reveal the actual history which lies stored a few feet beneath her surface. The object of this paper is to collect together the scattered scraps of information which exist as to the remains of Verulamium, so that in the event of any excavations being sanctioned and undertaken in the future, it may be known what has been already done. These scraps of information are of so meagre a kind that I have been doubtful during the writing of this paper whether they were really worth bringing together, but having committed myself to the subject, I felt bound to go on. -

Ancientcoins

ANCIENT COINS GREEK 6 Macedon, Alexander the Great, silver tetradrachm. posthumous issue, Temnos, c. 188-170 BC. head of Herakles facing r., with the features of Alexander (?), wearing a lionskin headdress. rev. Zeus seated l., on throne, holding sceptre and eagle, amphora and vine leaves in l., field, monogram below throne, wt.15.90gms (Price 1678), about very fine £60-70 *ex Derek Aldred Collection 1 Greek Italian and Sicilian, bronze units, various sizes, issues and dates. Bruttium, Taenum, 7 Macedon, Alexander the Great, silver tetradrachm. Thurium, Syracuse, Mamertinoi, varying grades from posthumous issue, Temnos, c. 188-170 BC. head of fine to very fine (8) £50-80 Herakles facing r., with the features of Alexander *ex Derek Aldred Collection (?), wearing a lionskin headdress. rev. Zeus seated l., on throne, holding sceptre and eagle, amphora and vine leaves in l., field, monogram above, wt.15.97gms (Price 1688), about fine £40-50 *ex Derek Aldred Collection 2 Calabria, Tarentum, 3rd century BC, silver stater, very fine £100-150 8 Macedon, Alexander the Great, silver tetradrachm. posthumous issue, Odessos c. 90-80 BC. head of Herakles facing r., with the features of Alexander 3 Attica, Athens, c.300 BC, silver tetradrachm, bust (?), wearing a lionskin headdress. rev. Zeus seated l. of Athena, rev. owl, toned, very fine £200-300 on throne, holding sceptre and eagle, EKA below, star below throne, wt.15.65gms (Price 1197), 4 Attica, Athens, c.200 BC, silver tetradrachm, bust extremely fine, some nice iridescence £100-150 of Athena, rev. owl, toned, very fine £100-200 *ex Derek Aldred Collection 9 Macedon, Alexander the Great, silver tetradrachm. -

Early Britons in Cosgrove

Early Britons in Cosgrove The Catuvellauni When the Romans first came to Britain under Julius Caesar in 55 BC there were already tribes living there who had divided territories and recognised areas which could be mapped out. The Catuvellauni were probably a Belgic tribe from the North Sea or Baltics, part of the third wave of Celtic settlers in Britain in the second century BC. They may have been related to the Catalauni, a Belgic tribe of Gaul. The Catuvellauni lived in the modern counties of Hertfordshire, Bedfordshire and southern Cambridgeshire. Their territory also probably included tribes in what is today Buckinghamshire and parts of Oxfordshire. The tribal name possibly means 'good in battle'. Cassivellaunus, British war leader in 55 BC, is the first British individual known to history. He appears in Julius Caesar's Commentarii de Bello Gallico, as commander of British warriors opposing Caesar's second invasion of Britain. Caesar does not mention Cassivellaunus's tribe, but his territory, north of the River Thames, corresponds with that of the Catuvellauni at the time of the later invasion under Claudius. Cassivellaunus had been at constant war with other British tribes, and had overthrown the king of the Trinovantes, the most powerful tribe in Britain at the time Despite Cassivellaunus's harrying tactics, designed to prevent Caesar's army from foraging and plundering for food, Caesar advanced to the Thames. The only fordable point was defended and fortified with sharp stakes, but the Romans managed to cross it. Cassivellaunus dismissed most of his army and resorted to guerilla tactics, relying on his knowledge of the territory and the speed of his chariots.