Abc of Learning and Teaching in Medicine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Emergency Medical Services Program Policies – Procedures – Protocols

Emergency Medical Services Program Policies – Procedures – Protocols Protocols Table of Contents GENERAL PROVISIONS ................................................................................................ 3 DESTINATION DECISION SUMMARY-METRO BAKERSFIELD AREA ........................ 5 DETERMINATION OF DEATH ..................................................................................... 12 101 AIRWAY OBSTRUCTION ...................................................................................... 16 102 ALTERED LEVEL OF CONSCIOUSNESS ............................................................ 18 103 ALLERGIC REACTION/ANAPHYLAXIS ................................................................ 20 104 ASYSTOLE/ PULSELESS ELECTRICAL ACTIVITY ............................................. 22 105 BITES STINGS ENVENOMATION ......................................................................... 24 106 BRADYCARDIA ..................................................................................................... 26 107 BRIEF RESOLVED UNEXPLAINED EVENT ......................................................... 29 108 BURNS ................................................................................................................... 32 109 CHEMPACK ........................................................................................................... 35 110 CHEST PAIN OR ACUTE CORONARY SYNDROME ........................................... 37 111 CHEST TRAUMA .................................................................................................. -

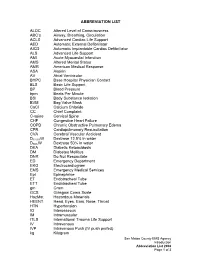

ABBREVIATION LIST ALOC Altered Level of Consciousness ABC's Airway, Breathing, Circulation ACLS Advanced Cardiac Life Suppo

ABBREVIATION LIST ALOC Altered Level of Consciousness ABC’s Airway, Breathing, Circulation ACLS Advanced Cardiac Life Support AED Automatic External Defibrillator AICD Automatic Implantable Cardiac Defibrillator ALS Advanced Life Support AMI Acute Myocardial Infarction AMS Altered Mental Status AMR American Medical Response ASA Aspirin AV Atrial Ventricular BHPC Base Hospital Physician Contact BLS Basic Life Support BP Blood Pressure bpm Beats Per Minute BSI Body Substance Isolation BVM Bag Valve Mask CaCl Calcium Chloride CC Chief Complaint C-spine Cervical Spine CHF Congestive Heart Failure COPD Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Edema CPR Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation CVA Cerebral Vascular Accident D12.5%W Dextrose 12.5% in water D50%W Dextrose 50% in water DKA Diabetic Ketoacidosis DM Diabetes Mellitus DNR Do Not Resuscitate ED Emergency Department EKG Electrocardiogram EMS Emergency Medical Services Epi Epinephrine ET Endotracheal Tube ETT Endotracheal Tube gm Gram GCS Glasgow Coma Scale HazMat Hazardous Materials HEENT Head, Eyes, Ears, Nose, Throat HTN Hypertension IO Interosseous IM Intramuscular ITLS International Trauma Life Support IV Intravenous IVP Intravenous Push (IV push prefed) kg Kilogram San Mateo County EMS Agency Introduction Abbreviation List 2008 Page 1 of 3 J Joule LOC Loss of Consciousness Max Maximum mcg Microgram meds Medication mEq Milliequivalent min Minute mg Milligram MI Myocardial Infarction mL Milliliter MVC Motor Vehicle Collision NPA Nasopharyngeal Airway NPO Nothing Per Mouth NS Normal Saline NT Nasal Tube NTG Nitroglycerine NS Normal Saline O2 Oxygen OB Obstetrical OD Overdose OPA Oropharyngeal Airway OPQRST Onset, Provoked, Quality, Region and Radiation, Severity, Time OTC Over the Counter PAC Premature Atrial Contraction PALS Pediatric Advanced Life Support PEA Pulseless Electrical Activity PHTLS Prehospital Trauma Life Support PID Pelvic Inflammatory Disease PO By Mouth Pt. -

FIRST AID QUICK SHEET- Airway and Breathing

FIRST AID QUICK SHEET Airway and Breathing After you have checked to make sure the scene is safe and put on gloves to protect yourself (Danger) and checked if the patient is responsive (Response), if you find the patient is not responding, you should think: ABC. First check for an Airway and Breathing. Instructions for the A and B steps of the DR. ABC acronym for first aid priorities are below: How to Adjust Someone’s Airway (A): 1. Gently swipe the mouth with one finger to ensure that no objects are blocking the airway. 2. Place two fingers under the casualties chin and one hand on the forehead. 3. Gently lift the chin with two fingers, removing the tongue from the back of the throat. 4. If transport is delayed, roll the casualty onto their side in the recovery position to allow fluids to drain from the mouth Note: If someone is able to speak, their airway is open. Breathing (B): 1. Always remember to look, listen, and feel when checking for breathing. 2. LOOK to see the chest rise and fall. 3. LISTEN to hear breath sounds. 4. Place one hand on the stomach and FEEL for breathing movement and FEEL beneath the nose for air movement. After you have secured an airway and checked for breathing, you may move on to check for bleeding in the C (circulation) step of DR. ABC. *Please be safe and practice first aid at your own risk. LFR International is not liable for injuries resulting from any first aid attempts. . -

Basic Trauma Overview - ABC

Basic Trauma Overview - ABC Dale Dangleben, MD, FACS 1 2 Team 3 Extended Team 4 Team Leader Decrease chaos / optimize care. – Remains calm – Maintains control and provides direction – Stays decisive – Sees the big picture (situational awareness) – Is open to other team members input – Directs resuscitation – Makes early decision to transfer the patients that exceed the local capabilities 5 Team Members − Know your roles in the trauma team − Remain calm − Be responsive to team leader −Voice suggestions or concerns 6 Responsibilities – Perform the Primary and secondary survey – Verbalize patient care – Report completed tasks 7 Responsibilities – Monitors the patient – Manual BP – Obtains IV access – Administers medications – Dresses wounds – Performs or assists in resuscitative procedures 8 Responsibilities Records data Ensures documentation accompanies patient upon transfer Assists team members as needed 9 Responsibilities – Obtains needed supplies – Coordinates communication with local and external resources – Assists team members as needed 10 Responsibilities • Place Oxygen on patient • Manage airway • Hold C spine • Manage ventilator if • Manage rapid infuser line patient intubated where indicated • Assists team members as needed 11 Organization of trauma resuscitation area – Basic adult and pediatric equipment for: • Airway management (cart) • IV access with warm fluids • Chest tube insertion • Hemorrhage control (tourniquets, pelvic binders) • Immobilization • Medications • Pediatric length/weight based tape (Broselow Tape) – Warming -

Abdominal Pain 02/02/2021

Medical Control Board Approved Protocols ABDOMINAL PAIN 02/02/2021 Follow Assessment, General Procedures Protocol EMR • Assess and support ABCs • Position of comfort • Supine if: • Trauma • Hypotension • Syncope • NPO • Monitor vital signs • Oxygen indicated for: • Unstable vitals • Severity of pain • Suspected GI bleed EMT • 12-lead – See CARDIAC-ECG/12 Lead Procedure A-EMT • IV – NS with standard tubing • Titrate fluid to patient’s needs – See Shock Protocol EMT-I/ • Cardiac monitoring PARAMEDIC • Pain management – See Acute Pain Management Protocol 199 March, 2021 Medical Control Board Approved Protocols This page intentionally left blank 200 March, 2021 Medical Control Board Approved Protocols ACUTE ADRENAL INSUFFICIENCY PROTOCOL 02/02/2021 Follow Assessment, General Procedures Protocol • Acute adrenal insufficiency (crisis) can occur in the following settings: - During neonatal period (undiagnosed adrenal insufficiency) - In patients with known, pre-existing adrenal insufficiency (e.g., Addison’s disease) - In patients who are chronically steroid dependent (i.e., taking steroids daily, long- term, for any number of medical conditions) - Adrenal crisis can be triggered by any acute stressor (e.g., trauma or illness), as well as by abrupt cessation of steroid use (for any reason). • Signs/symptoms of adrenal crisis: Altered mental status, seizures; generalized weakness, hypotension, hypoglycemia, hyperkalemia. • Notify hospital you are transporting known/suspected adrenal crisis patient • Emergency transport for: ALOC, hypotension, hypoglycemia, suspected hyperkalemia. Acute adrenal crisis is an immediately life-threatening emergency, and must be treated aggressively EMR • PMH, Take thorough history of patient’s steroid use/dependence. Determine if the patient is on oral hydrocortisone. • Assess and support ABC’s • Oxygen therapy, as needed • Monitor vitals EMT • Check blood glucose • If blood glucose is <60: administer glucose solution orally if the patient is awake and able to protect own airway • Obtain 12 lead ECG; if time permitted. -

Triage and Scenario

Triage and Scenario By Bryan Lewis Triage Triage: Is a rapid approach to prioritizing a large number of patients Incident Casualty Collection Triage Site Point Officer/Treatment/Transport S imple T riage A nd R apid T reatment Triage ● Triage should be performed RAPIDLY ● Utilize START Triage to determine priority ● 30–60 seconds per patient ● Affix tag on left upper arm or leg – Triage 1. Scene Safety BSI and Identify number of patients, and types of injuries, communicate to EMS 2. Clear the “walking wounded” with verbal instruction: If you can hear me and you can move, walk to… (Use a PA System if Possible) 3. Direct patients to the casualty collection point (CCP) or treatment area for detailed assessment and medical care Green Minor Manager/Triage Officer will be the area to control patients and manage area 4. Green tag will be issued at the CCP These patients may be classified as MINOR START Triage Now use START to assess and categorize the remaining patients… USE Color System START-Triage Now categorize the patients by assessing each patient’s RPMs… ✓Respirations ✓Pulse ✓Mental Status START—RPM RESPIRATIONS Is the patient breathing? Yes Adult – respirations > 30 = Red/Immediate Pediatric – respirations < 15 or > 45 = Red/Immediate Adult – respirations < 30 = check pulse Pediatric – respirations > 15 and < 45 = check pulse START—RPM RESPIRATIONS Is the Patient Breathing? No Reposition the airway… Respirations begin = IMMEDIATE/RED If patient doesn’t breath . ▪ Adult – deceased = BLACK ▪ Pediatric: Pulse Present – give 5 rescue breaths -

Paramedic Update

PARAMEDIC UPDATE 2020 AGENDA Protocol format New medications Base contact requirements Against Medical Advice Pediatric King Airway Protocol changes New Policies Determination of death Online Certifications- Image trend NEW PROTOCOL FORMAT Public safety, EMT, and Public safety personal can Adults and Pediatric are on Paramedic protocols are in only perform skills in the top the same page. one document. canary yellow section Anything listed in the yellow EMT’s can perform any skills Paramedics will start with ALS section is a standing in the green BLS section the BLS section (BLS before order. Base contact must be located below the public ALS!) and move down into attempted for anything in the safety area. the ALS section as needed. red “base hospital contact required” section. NEW PROTOCOL FORMAT Adults Pediatrics (13 years and under) Public Safety First Aid Procedures: Only Public Safety First Aid Procedures: Only • Remove nearby objects to prevent injury to Patient. Place • Remove nearby objects to prevent injury to Patient. Place patient in recovery position on left side patient in recovery position on left side • Give Oxygen if available • Give Oxygen if available • Request Fire/EMS • Request Fire/EMS • Public safety will start here BLS Procedures: EMT’s and Paramedics start here BLS Procedures: EMT’s and Paramedics start here • Support ABC’s • Support ABC’s • Give Oxygen only if Spo2 < 94% or if in Respiratory Distress • Give Oxygen only if Spo2 <94% or if in Respiratory Distress • Blood Glucose Check, if hypoglycemic enter appropriate • Blood Glucose check, if hypoglycemic enter appropriate protocol protocol • EMT and Paramedic start here • If Focal seizure, place patient in position of comfort, rapid • If Focal seizure, place patient in position of comfort, rapid transport or ALS Rendezvous transport or ALS Rendezvous • If full body tonic/clonic seizure, prepare to support • If full body tonic/clonic seizure, prepare to support respirations, provide cooling measures if febrile respirations. -

First Aid & CPR Training Inc. “At a Glance”

First Aid & CPR Training Inc. REFERENCE MANUAL “At A Glance” 2 Introduction 3 Emergency Scene Management 13 Life Threatening Priorities 15 Levels of Consciousness and Shock 20 Heart Attacks, Strokes, and Heart-Smart Awareness 26 CPR 30 Automated External Defibrillation (AED) 32 Health Care Providers (HCP) 35 Choking 40 Wounds and Bleeding 46 Medical Conditions (Asthma, Allergies, Diabetes and Seizures) 54 Bone and Joint Injuries 58 Head and Spinal Injuries 62 Eye, Ear and Nose Injuries 65 Burns 68 Poisons 70 Opioid Overdoses 71 Cold and Heat Injuries 76 Rescue Carries 77 In Closing 78 Quiz ATTENTION Please pay extra attention when you see this symbol. Introduction Hello from all of us at Lifesaver 101 First Aid & CPR Training Inc. Thank you for selecting Lifesaver 101 to provide you with educational, enjoyable and effective First Aid and CPR training. This reference manual is to be used with the “hands- on” approach to our interactive training. Please enjoy your program. Learning objectives include clearly determining when to call 9-1-1 and what to do while waiting for help to arrive. Being confident in FIRST AID & CPR includes your ability to assess quickly and competently the components of an emergency situation. As a First Aider you will always follow the steps of Emergency Scene Management (ESM) by completing the Lifesaver 101 Rules of 123 & ABC and providing ongoing care. Any scene of a medical emergency can be overwhelming for a first aider. By taking a first aid course you are equipping yourself with the knowledge you will need to become and effective and confident first aider. -

The Efficiency of Bag-Valve Mask Ventilations by Medical First Responders and Basic Emergency Medical Technicians

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Theses Digitization Project John M. Pfau Library 2003 The efficiency of bag-valve mask ventilations by medical first responders and basic emergency medical technicians John Vincent Commander Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project Part of the Vocational Education Commons Recommended Citation Commander, John Vincent, "The efficiency of bag-valve mask ventilations by medical first responders and basic emergency medical technicians" (2003). Theses Digitization Project. 2310. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project/2310 This Project is brought to you for free and open access by the John M. Pfau Library at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses Digitization Project by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE EFFICIENCY OF BAG-VALVE MASK VENTILATIONS BY MEDICAL FIRST RESPONDERS AND BASIC EMERGENCY MEDICAL TECHNICIANS A Project Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Education: Career and Technical Education by John Vincent Commander September 2003 THE EFFICIENCY OF BAG-VALVE MASK VENTILATIONS BY MEDICAL FIRST RESPONDERS AND BASIC EMERGENCY MEDICAL TECHNICIANS A Project Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by John Vincent Commander September 2003 Approved by: © 2003 John Vincent Commander ABSTRACT• Bag-valve mask (BVM) ventilation maintains a patient's oxygenation and ventilation until a more definitive artificial airway can be established. In the prehospital setting of a traffic collision-or • medical aid scene this is performed by an Emergency Medical Technician or medical first responder. -

Code Blue Simulation Curriculum Overview

L. Brown, MD 1 Code Blue Simulation Curriculum Overview Code Blue Simulation Curriculum Stable Ventricular Tachycardia with deterioration to Pulseless VT/VF Cardiac Arrest Project Goals Primary Goal: To improve the ACLS algorithm adherence and leadership skills of medicine residents when responding to in‐hospital cardiac arrest (IHCA) in the ICU. Secondary Goal: To improve inter‐professional communication, leadership, and teamwork during code blue (including RN, RT, and pharmacy) in the ICU. Objectives Upon completion of this curriculum, participants will: 1. Adhere to ACLS algorithms and AHA/ACCF guidelines when leading resuscitation efforts during code blue. 2. Demonstrate awareness and management of practical factors that contribute to success of resuscitation efforts. 3. Demonstrate effective leadership, communication, and teamwork skills during code blue. 4. Physician participants will increase confidence and preparedness for leading real‐world code blue. Participants ICU MD interns, residents, and fellows ICU RN Respiratory Therapist Pharmacist Schedule Ideally, this curriculum is implemented on a recurring basis based upon trainee rotation schedule. Each month prior to trainee intensive care unit (ICU) rotation, an interprofessional team as described above will be invited to participate in a 90‐minute simulation session. The ICU is an ideal setting in which to implement this interprofessional curriculum, as it has an existing interprofessional team structure and often has a higher rate of code blue than a typical medical/surgical unit. Representatives from each of the above professions (RT, pharmacy, chief resident, ICU RN manager) will help to find a mutually agreeable time to schedule the simulation each month to maximize interprofessional participation. Curriculum Components The curriculum consists of three components: simulation exercise of stable VT which deteriorates into pulseless VT/VF, interactive group session with debriefing and review of relevant communication as well as medical factors, and an unannounced in‐unit mock code blue. -

I Guideline for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care – Brazilian Society of Cardiology: Executive Summary

Artigo Especial I Diretriz de Ressuscitação Cardiopulmonar e Cuidados Cardiovasculares de Emergência da Sociedade Brasileira de Cardiologia: Resumo Executivo I Guideline for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care – Brazilian Society of Cardiology: Executive Summary Maria Margarita Gonzalez, Sergio Timerman, Renan Gianotto de Oliveira, Thatiane Facholi Polastri, Luis Augusto Palma Dallan, Sebastião Araújo, Silvia Gelás Lage, André Schmidt, Claudia San Martín de Bernoche, Manoel Fernandes Canesin, Frederico José Neves Mancuso, Maria Helena Favarato Sociedade Brasileira de Cardiologia, Rio de Janeiro, RJ – Brasil Resumo Introdução Apesar de avanços nos últimos anos relacionados à Embasada no consenso científico internacional de 2010 e prevenção e a tratamento, muitas são as vidas perdidas atualizada com algumas novas evidências científicas recolhidas anualmente no Brasil relacionado à parada cardíaca e a nesses dois últimos anos, ocorre a edição da I Diretriz de eventos cardiovasculares em geral. O Suporte Básico de Vida Ressuscitação Cardiopulmonar e Cuidados Cardiovasculares envolve o atendimento às emergências cardiovasculares da Sociedade Brasileira de Cardiologia que visa atender às principalmente em ambiente pré-hospitalar, enfatizando realidades brasileiras. reconhecimento e realização precoces das manobras de ressuscitação cardiopulmonar com foco na realização Aspectos epidemiológicos de compressões torácicas de boa qualidade, assim como Apesar de avanços nos últimos anos relacionados à na rápida desfibrilação, por meio da implementação prevenção e a tratamento, muitas são as vidas perdidas dos programas de acesso público à desfibrilação. Esses anualmente no Brasil relacionadas à parada cardiorrespiratória aspectos são de fundamental importância e podem fazer (PCR), ainda que não tenhamos a exata dimensão do diferença no desfecho dos casos como sobrevida hospitalar problema pela falta de estatísticas robustas a esse respeito. -

Acute Atropine Intoxication with Psychiatric Symptoms by Herbal Infusion of Pulmonaria Officinalis (Lungwort)

Eur. J. Psychiat. Vol. 21, N.° 2, (93-97) 2007 Keywords: Pulmonaria Officinalis, Herbal reme- dies, Atropine intoxication, Delirium. Acute atropine intoxication with psychiatric symptoms by herbal infusion of Pulmonaria officinalis (Lungwort) Enrique Baca-García, M.D.* Hilario Blasco-Fontecilla, M.D.** Carlos Blanco, M.D.*** Carmen Díaz-Sastre, M.D.**** María Mercedes Pérez-Rodríguez, M.D.**** Jerónimo Sáiz-Ruiz, M.D., Ph.D.****,***** * Psychiatry Department. Fundación Jiménez-Díaz Hospital, Madrid, Spain ** Doctor R. Lafora Hospital, Madrid, Spain *** Columbia College of Physicians and Surgeons. Presbyterian Hospital, New York, USA **** Psychiatry Department. Ramón y Cajal Hospital, Madrid, Spain ***** University of Alcala, Madrid, Spain SPAIN, USA ABSTRACT – Background and objectives: Lungwort infusion is a preparation extracted from Pulmonaria officinalis which is occasionally used as a folk remedy for the common cold. The current report aims to describe acute atropine intoxications with delirium caused by Lungwort infusion in several members of the same family. Methods: Description of three case reports. Search of literature through Medline. Results: Three generations of a same family presented acute and moderately severe atropine intoxications after drinking an infusion prepared with Pulmonaria officinalis. Conclusions: Despite the lack of scientific evidence for its clinical use, medicinal plants continue being widely used. In spite of severe adverse effects reported, the general thought is that herbal remedies are harmless. To our knowledge, this is the first report of acute atropine intoxications with psychiatric symptoms secondary to Pulmonaria offici- nalis in several members of a family. We suspect that the lungwort infusion may have been contaminated with some other substance with atropinic properties.