First Responder EMS Curriculum for Training Centers in Eurasia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

First Responder (2013)

THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS This PDF is available at http://nap.edu/22451 SHARE The Legal Definitions of First Responder (2013) DETAILS 30 pages | 8.5 x 11 | PAPERBACK ISBN 978-0-309-28369-4 | DOI 10.17226/22451 CONTRIBUTORS GET THIS BOOK Bricker, Lew R. C.; Petermann, Tanya N.; Hines, Margaret; and Sands, Jocelyn FIND RELATED TITLES SUGGESTED CITATION National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2013. The Legal Definitions of First Responder . Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/22451. Visit the National Academies Press at NAP.edu and login or register to get: – Access to free PDF downloads of thousands of scientific reports – 10% off the price of print titles – Email or social media notifications of new titles related to your interests – Special offers and discounts Distribution, posting, or copying of this PDF is strictly prohibited without written permission of the National Academies Press. (Request Permission) Unless otherwise indicated, all materials in this PDF are copyrighted by the National Academy of Sciences. Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. The Legal Definitions of “First Responder” November 2013 NATIONAL COOPERATIVE HIGHWAY RESEARCH PROGRAM Responsible Senior Program Officer: Stephan A. Parker Research Results Digest 385 THE LEGAL DEFINITIONS OF “FIRST RESPONDER” This digest presents the results of NCHRP Project 20-59(41), “Legal Definition of ‘First Responder’.” The research was conducted by Lew R. C. Bricker, Esquire, and Tanya N. Petermann, Esquire, of Smith Amundsen, Chicago, IL; Margaret Hines, Esquire; and Jocelyn Sands, J. D. James B. McDaniel was the Principal Investigator. INTRODUCTION Congress and in some congressional bills that were not enacted into law. -

Emergency Medical Services Program Policies – Procedures – Protocols

Emergency Medical Services Program Policies – Procedures – Protocols Protocols Table of Contents GENERAL PROVISIONS ................................................................................................ 3 DESTINATION DECISION SUMMARY-METRO BAKERSFIELD AREA ........................ 5 DETERMINATION OF DEATH ..................................................................................... 12 101 AIRWAY OBSTRUCTION ...................................................................................... 16 102 ALTERED LEVEL OF CONSCIOUSNESS ............................................................ 18 103 ALLERGIC REACTION/ANAPHYLAXIS ................................................................ 20 104 ASYSTOLE/ PULSELESS ELECTRICAL ACTIVITY ............................................. 22 105 BITES STINGS ENVENOMATION ......................................................................... 24 106 BRADYCARDIA ..................................................................................................... 26 107 BRIEF RESOLVED UNEXPLAINED EVENT ......................................................... 29 108 BURNS ................................................................................................................... 32 109 CHEMPACK ........................................................................................................... 35 110 CHEST PAIN OR ACUTE CORONARY SYNDROME ........................................... 37 111 CHEST TRAUMA .................................................................................................. -

Understanding Code Status

Understanding Code Status It’s important to consider the type of Code status conversations should include questions such as: medical treatments you want before • Which treatments, if any, might you not want to a medical emergency occurs. All receive? patients must choose a code status. • Under which circumstances, if any, do you believe life-prolonging treatments would not be desirable? Understanding what each code means • How has your past experience, if any, created your and selecting a code status will help opinion about resuscitation procedures for yourself? your caregivers and loved ones follow It is very important to have this discussion your wishes. before a medical emergency occurs. What is Code Status? Choosing your Code Status All patients who are admitted to a hospital or an You will work with your health care provider to outpatient facility (such as a dialysis center or discuss the types of resuscitation procedures and outpatient surgery center) will be asked to choose advance medical treatments you would benefit from a code status for the duration of their stay. and the type that you may not want if a medical emergency were to occur. This conversation should Your chosen code status describes the type of help you determine which code status is right for you resuscitation procedures (if any) you would like the to live well with your goals in mind. health care team to conduct if your heart stopped beating and/or you stopped breathing. During this Outcomes after CPR medical emergency, resuscitation procedures must Unfortunately, what you see on TV is not reality. -

Emergency Medical System 2021 Patient Treatment Protocols

2021 Patient Treatment Protocols Effective January 1, 2021 CONTENTS Table of Contents Preface Section ...........................................................................................................00.000 EMS Provider Scope of Practice and Nomenclature .....................................................00.010 Death in the Field ........................................................................................................00.020 Dying and Death, POLST, Do Not Attempt Resuscitation Orders ..............................00.030 Medical Control for Drugs and Procedures ..................................................................00.040 Treatment ......................................................................................................... Section 10.000 Abdominal Pain ...........................................................................................................10.010 Altered Mental Status and Coma ..................................................................................10.020 Anaphylaxis and Allergic Reaction ................................................................................10.030 Burns ...........................................................................................................................10.040 Cardiac Arrest ..............................................................................................................10.050 Emergency Medical Responder/EMT Paramedic/EMT-Intermediate Quick Reference to Pediatric Drugs Cardiac Dysrhythmias ..................................................................................................10.060 -

MASS CASUALTY TRAUMA TRIAGE PARADIGMS and PITFALLS July 2019

1 Mass Casualty Trauma Triage - Paradigms and Pitfalls EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Emergency medical services (EMS) providers arrive on the scene of a mass casualty incident (MCI) and implement triage, moving green patients to a single area and grouping red and yellow patients using triage tape or tags. Patients are then transported to local hospitals according to their priority group. Tagged patients arrive at the hospital and are assessed and treated according to their priority. Though this triage process may not exactly describe your agency’s system, this traditional approach to MCIs is the model that has been used to train American EMS As a nation, we’ve got a lot providers for decades. Unfortunately—especially in of trailers with backboards mass violence incidents involving patients with time- and colored tape out there critical injuries and ongoing threats to responders and patients—this model may not be feasible and may result and that’s not what the focus in mis-triage and avoidable, outcome-altering delays of mass casualty response is in care. Further, many hospitals have not trained or about anymore. exercised triage or re-triage of exceedingly large numbers of patients, nor practiced a formalized secondary triage Dr. Edward Racht process that prioritizes patients for operative intervention American Medical Response or transfer to other facilities. The focus of this paper is to alert EMS medical directors and EMS systems planners and hospital emergency planners to key differences between “conventional” MCIs and mass violence events when: • the scene is dynamic, • the number of patients far exceeds usual resources; and • usual triage and treatment paradigms may fail. -

Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation EFFECTIVE DATE: October 2007 SUPERCEDES DATE: May 2004

HEALTH SERVICES POLICY & PROCEDURE MANUAL North Carolina Department Of Correction SECTION: Care and Treatment of Patient Division Of Prisons POLICY # TX I-7 PAGE 1 of 3 SUBJECT: Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation EFFECTIVE DATE: October 2007 SUPERCEDES DATE: May 2004 PURPOSE To provide guidelines in case of a medical emergency requiring Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR). To re-establish effective ventilation and circulation. To prevent irreversible brain damage. To provide an efficient and organized team approach in response to a medical emergency requiring Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR). To delineate the responsibilities of staff in the event of a medical emergency requiring Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR). POLICY All Health Services personnel will be certified in Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR) including Automated External Defibrillator (AED) according to guidelines set forth by the American Heart Association (AHA) “Basic Life Support Health Care Provider Course” (BLS-HCP). It is the responsibility of the employee to maintain current BLS-HCP CPR certification, with renewal every two years. Dental hygienists are required to renew annually per professional standards. Failure to recertify may result in the disciplinary process being initiated. Custody Officers are trained to provide CPR according to guidelines set forth by the American Heart Association “HeartSaver-AED Course”. Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation will be initiated on all patients demonstrating cardiac and/or respiratory arrest (i.e., absence of spontaneous respirations and/or pulseless), with the exception of: a. Decapitation b. Body tissue decomposition noted c. Verification of a current Do Not Resuscitate (DNR) order originated or approved by a physician in the employ of N.C. Division of Prisons. (1) Most patients with current DNR orders will be maintained in a Hospice unit, health ward, or infirmary with DNR located in patient’s chart with staff knowledge of such. -

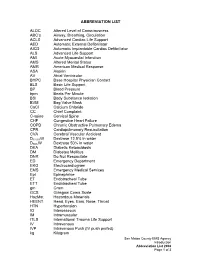

ABBREVIATION LIST ALOC Altered Level of Consciousness ABC's Airway, Breathing, Circulation ACLS Advanced Cardiac Life Suppo

ABBREVIATION LIST ALOC Altered Level of Consciousness ABC’s Airway, Breathing, Circulation ACLS Advanced Cardiac Life Support AED Automatic External Defibrillator AICD Automatic Implantable Cardiac Defibrillator ALS Advanced Life Support AMI Acute Myocardial Infarction AMS Altered Mental Status AMR American Medical Response ASA Aspirin AV Atrial Ventricular BHPC Base Hospital Physician Contact BLS Basic Life Support BP Blood Pressure bpm Beats Per Minute BSI Body Substance Isolation BVM Bag Valve Mask CaCl Calcium Chloride CC Chief Complaint C-spine Cervical Spine CHF Congestive Heart Failure COPD Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Edema CPR Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation CVA Cerebral Vascular Accident D12.5%W Dextrose 12.5% in water D50%W Dextrose 50% in water DKA Diabetic Ketoacidosis DM Diabetes Mellitus DNR Do Not Resuscitate ED Emergency Department EKG Electrocardiogram EMS Emergency Medical Services Epi Epinephrine ET Endotracheal Tube ETT Endotracheal Tube gm Gram GCS Glasgow Coma Scale HazMat Hazardous Materials HEENT Head, Eyes, Ears, Nose, Throat HTN Hypertension IO Interosseous IM Intramuscular ITLS International Trauma Life Support IV Intravenous IVP Intravenous Push (IV push prefed) kg Kilogram San Mateo County EMS Agency Introduction Abbreviation List 2008 Page 1 of 3 J Joule LOC Loss of Consciousness Max Maximum mcg Microgram meds Medication mEq Milliequivalent min Minute mg Milligram MI Myocardial Infarction mL Milliliter MVC Motor Vehicle Collision NPA Nasopharyngeal Airway NPO Nothing Per Mouth NS Normal Saline NT Nasal Tube NTG Nitroglycerine NS Normal Saline O2 Oxygen OB Obstetrical OD Overdose OPA Oropharyngeal Airway OPQRST Onset, Provoked, Quality, Region and Radiation, Severity, Time OTC Over the Counter PAC Premature Atrial Contraction PALS Pediatric Advanced Life Support PEA Pulseless Electrical Activity PHTLS Prehospital Trauma Life Support PID Pelvic Inflammatory Disease PO By Mouth Pt. -

VHA Dir 1101.05(2), Emergency Medicine

Department of Veterans Affairs VHA DIRECTIVE 1101.05(2) Veterans Health Administration Transmittal Sheet Washington, DC 20420 September 2, 2016 EMERGENCY MEDICINE 1. REASON FOR ISSUE: This Veterans Health Administration (VHA) directive establishes policy and procedures for VHA Emergency Departments (EDs) and Urgent Care Centers (UCCs). 2. SUMMARY OF MAJOR CHANGES: This directive replaces the previous VHA handbook establishing procedures for VA EDs and UCCs. The following major changes are included: a. Information on EDs, UCCs, diversion, Mental Health, sexual assault, temporary beds, ED/UCC staffing, and Emergency Department Integration Software (EDIS) was added. b. Information about the Intermediate Healthcare Technician Program. c. Information about the ED and Women’s Health, Out of Operating Room Airway Management and Ensuring Correct Surgery and Invasive Procedures, and geriatric emergency care. d. Information about the Emergency Medicine Improvement Initiative and support resources. 3. RELATED ISSUE: None. 4. RESPONSIBLE OFFICE: The Office of Patient Care Services (10P), Specialty Care Services (10P4E), is responsible for the content of this VHA Handbook. Questions may be referred to the National Director for Emergency Medicine at 202-461-7120. 5. RESCISSIONS: VHA Handbook 1101.05, dated May 12, 2010; VHA Directive 1051, dated February 21, 2014; VHA Directive 1079, dated February 3, 2014; VHA Directive 2010-008, dated February 22, 2010; VHA Directive 2010-014, dated March 25, 2010; VHA Directive 1009, dated August 28, 2013; VHA Directive 2010-010, dated March 2, 2010; VHA Directive 2011-029, dated July 15, 2011; and VHA Directive 2009-069, dated December 16, 2009 are rescinded. 6. RECERTIFICATION: This VHA directive is scheduled for recertification on or before the last working day of September 2021. -

Emergency Medical Services Statutes and Regulations

Emergency Medical Services Statutes and Regulations Printed: August 2016 Effective: September 11, 2016 1 9/16/2016 Statutes and Regulations Table of Contents Title 63 of the Oklahoma Statutes Pages 3 - 13 Sections 1-2501 to 1-2515 Constitution of Oklahoma Pages 14 - 16 Article 10, Section 9 C Title 19 of the Oklahoma Statutes Pages 17 - 24 Sections 371 and 372 Sections 1- 1201 to 1-1221 Section 1-1710.1 Oklahoma Administrative Code Pages 25 - 125 Chapter 641- Emergency Medical Services Subchapter 1- General EMS programs Subchapter 3- Ground ambulance service Subchapter 5- Personnel licenses and certification Subchapter 7- Training programs Subchapter 9- Trauma referral centers Subchapter 11- Specialty care ambulance service Subchapter 13- Air ambulance service Subchapter 15- Emergency medical response agency Subchapter 17- Stretcher aid van services Appendix 1 Summary of rule changes Approved changes to the June 11, 2009 effective date to the September 11, 2016 effective date 2 9/16/2016 §63-1-2501. Short title. Sections 1-2502 through 1-2521 of this title shall be known and may be cited as the "Oklahoma Emergency Response Systems Development Act". Added by Laws 1990, c. 320, § 5, emerg. eff. May 30, 1990. Amended by Laws 1999, c. 156, § 1, eff. Nov. 1, 1999. NOTE: Editorially renumbered from § 1-2401 of this title to avoid a duplication in numbering. §63-1-2502. Legislative findings and declaration. The Legislature hereby finds and declares that: 1. There is a critical shortage of providers of emergency care for: a. the delivery of fast, efficient emergency medical care for the sick and injured at the scene of a medical emergency and during transport to a health care facility, and b. -

Medical Emergency Minimum Standard: 5120:1-8-09(E) Revised

Section 6: Jail Emergencies Response Plan Subject: Medical Emergency Minimum Standard: 5120:1-8-09(E) Revised: Authorized: _____________________________ Effective date: ________________________ Sheriff Paul A. Sigsworth POLICY The Erie County Jail shall provide 24-hour emergency medical, dental, and mental health care services. All corrections officers are trained to respond to medical emergencies, and will promptly implement emergency medical procedures for inmates who are in need of emergency medical attention. PROCEDURE A. Policy 1. Any Corrections Officer or member of the Medical Staff who is available will respond when a Medical Emergency is reported and initiate care. B. Definitions: 1. The following occurrence define an emergency, which may result from, but not limited to, injury from attempted suicide or injury from assault. a. Sever Bleeding: i. Apply clean/sterile pressure dressing to wound, apply pressure by use of hands. Monitor for signs and symptoms of shock. Follow American Red Cross Heartsaver Guidelines. b. Unconsciousness: i. Maintain body alignment, observe vital signs, respiration, etc., for any change until the doctor or emergency squad arrives. Monitor for deteriorating status. Follow American Red Cross Heartsaver Guidelines. c. Serious Breathing Difficulties: i. Keep in a semi-sitting position. Loosen or remove all tight clothing, observe and reassure. Monitor for deteriorating status. Follow American Red Cross Heartsaver Guidelines. d. Head, Neck, and/or Spinal Injury: i. Keep inmate quiet. Stop any bleeding, maintain neck alignment, observe and reassure. Monitor for deteriorating status. Follow American Red Cross Heartsaver Guidelines. e. Severe Burns: i. Do not remove clothing. Apply clean wet dressing to area. Prevent chilling, observe and reassure. -

Integrating Emergency Medical Services in the Fire Department

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange MTAS Publications: Full Publications Municipal Technical Advisory Service (MTAS) 4-2007 Integrating Emergency Medical Services in the Fire Department Gary West Municipal Technical Advisory Service Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_mtaspubs Part of the Public Administration Commons The MTAS publications provided on this website are archival documents intended for informational purposes only and should not be considered as authoritative. The content contained in these publications may be outdated, and the laws referenced therein may have changed or may not be applicable to your city or circumstances. For current information, please visit the MTAS website at: mtas.tennessee.edu. Recommended Citation West, Gary, "Integrating Emergency Medical Services in the Fire Department" (2007). MTAS Publications: Full Publications. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_mtaspubs/84 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Municipal Technical Advisory Service (MTAS) at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in MTAS Publications: Full Publications by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INTEGRATING EMERGENCY MEDICAL SERVICES IN THE FIRE DEPARTMENT Fire/EMS First Responders: It’s just a matter of time Gary L. West, Fire Management Consultant April 2007 INTEGRATING EMERGENCY MEDICAL SERVICES IN THE FIRE DEPARTMENT Fire/EMS First Responders: It’s just a matter of time Gary L. West, Fire Management Consultant This publication was written with the assistance and editing of Richard F. Land, Tennessee Department of Health, Bureau of Health Licensure and Regulation, Division of Emergency Medical Services, Nashville, Tennessee. -

Emergency Ambulance and First Responder Staffing, Medications, Medical Equipment, and Supplies

POLICY NO: EQP 1 DATE ISSUED: Apr. 2021 EMERGENCY AMBULANCE AND FIRST RESPONDER STAFFING, MEDICATIONS, MEDICAL EQUIPMENT, AND SUPPLIES I. PURPOSE This policy establishes requirements for emergency ambulance and first responder staffing, medications, equipment, and supplies for emergency ambulances, first responder apparatus, and EMS supervisor vehicles. This policy further defines restocking requirements of medications, medical supplies, and equipment. II. AUTHORITY California Health and Safety Code, Division 2.5, §1798 III. DEFINITIONS Advanced Life Support (“ALS”) Ambulance [or “Paramedic Ambulance”]: An ambulance authorized by LEMSA to provide ALS emergency services within San Mateo County. Advanced Life Support (“ALS”) First Responder Unit (“FRU”): A fire department first responder authorized by LEMSA to provide ALS emergency services within San Mateo County. Basic Life Support (“BLS”) Ambulance: An ambulance authorized by LEMSA to provide BLS emergency services within San Mateo County. Basic Life Support (“BLS”) First Responder Unit (“FRU”): A fire department first responder authorized by LEMSA to provide BLS emergency services within San Mateo County. Emergency Medical Services Agency (“LEMSA”) [or “Agency”]: The San Mateo County EMS Agency. IV. STAFFING REQUIREMENTS A. ALS ambulance shall be staffed with a minimum of one currently licensed and LEMSA accredited paramedic and one currently California certified EMT. B. ALS first responder apparatus shall be staffed with a minimum of two personnel, at least one of whom is a currently licensed and LEMSA accredited paramedic. C. BLS first responder apparatus shall be staffed with a minimum of two personnel, at least Page 1 of 6 one of whom is a currently California certified EMT. D. EMS Supervisor vehicles shall be staffed with a minimum of one currently licensed and LEMSA accredited paramedic.