Story of Railbanking 7-06

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WWRP Funding Scenerios

Washington Wildlife and Recreation Program 2015-2017 Critical Habitat Projects Grants Awarded at Different Legislative Funding Levels Number Grant Applicant Rank and Type Project Name Grant Applicant Request Match Total $40 Million $50 Million $60 Million $70 Million $80 Million $90 Million $95 Million $97 Million 1 14-1085A Mountain View Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife $4,000,000 $4,000,000 $4,000,000 $4,000,000 $4,000,000 $4,000,000 $4,000,000 $4,000,000 $4,000,000 $4,000,000 2 14-1096A Simcoe Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife $3,000,000 $3,000,000 $3,000,000 $3,000,000 $3,000,000 $3,000,000 $3,000,000 $3,000,000 $3,000,000 $3,000,000 3 14-1087A Mid Columbia-Grand Coulee Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife $4,000,000 $4,000,000 $1,730,000 $2,166,500 $3,476,000 $4,000,000 $4,000,000 $4,000,000 $4,000,000 $4,000,000 4 14-1090A Heart of the Cascades Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife $4,000,000 $4,000,000 $785,500 $2,095,000 $3,404,500 $4,000,000 $4,000,000 5 14-1091A Cowiche Watershed Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife $2,200,000 $2,200,000 $59,250 $321,150 6 14-1089A Tunk Valley Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife $2,000,000 $2,000,000 7 14-1099A Kettle River Corridor Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife $1,000,000 $1,000,000 8 14-1609C Sage Grouse Habitat Acquisition in Deep Creek Foster Creek Conservation District $302,000 $303,152 $605,152 $20,502,000 $303,152 $20,805,152 $8,730,000 $9,166,500 $10,476,000 $11,785,500 $13,095,000 $14,404,500 $15,059,250 $15,321,150 Type Abbreviations: -

WASHINGTON STATE PARKS and RECREATION COMMISSION 1111 Israel Rd S.W

Don Hoch Director STATE OF WASHINGTON WASHINGTON STATE PARKS AND RECREATION COMMISSION 1111 Israel Rd S.W. • P.O. Box 42650 • Olympia, WA 98504-2650 • (360) 902-8500 TDD (Telecommunications Device for the Deaf): (360) 664-3133 www.parks.wa.gov STATE ENVIRONMENTAL POLICY ACT DETERMINATION OF NON-SIGNIFICANCE Date of Issuance: January 14, 2019 Project Name: Klickitat Trail Development Proponent: Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission Lead Agency: Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission Description of proposal: This Klickitat Trail Development project continues previous trail planning and improvement work completed by the U.S. Forest Service (USFS) and Washington State Parks. This is the first phase of a phased environmental review under the State Environmental Policy Act (SEPA) that expands on the previous 2003 Environmental Assessment prepared by the USFS, and adopted by Washington State Parks in 2005 as the document used for the original Determination of Non-significance (DNS) to satisfy SEPA requirements. This phased review specifically addresses updated site information identified since the original review, and new information for project modifications or new projects not previously reviewed. Phase 1 of this project proposes to construct a trailhead at Pitt and resurface approximately 12 miles of trail through Swale Canyon. Work also includes minor structural repairs, new decking and railings on seven existing trestles, replacement of one trestle with a free span bridge, and removal of one existing damaged trestle in Swale Canyon. Additionally, a preliminary concept for a potential trailhead at Warwick will be completed. Location of Proposal: Project activities will occur along portions of the Klickitat State Park Trail right-of-way corridor in Klickitat County. -

Washington State's Scenic Byways & Road Trips

waShington State’S Scenic BywayS & Road tRipS inSide: Road Maps & Scenic drives planning tips points of interest 2 taBLe of contentS waShington State’S Scenic BywayS & Road tRipS introduction 3 Washington State’s Scenic Byways & Road Trips guide has been made possible State Map overview of Scenic Byways 4 through funding from the Federal Highway Administration’s National Scenic Byways Program, Washington State Department of Transportation and aLL aMeRican RoadS Washington State Tourism. waShington State depaRtMent of coMMeRce Chinook Pass Scenic Byway 9 director, Rogers Weed International Selkirk Loop 15 waShington State touRiSM executive director, Marsha Massey nationaL Scenic BywayS Marketing Manager, Betsy Gabel product development Manager, Michelle Campbell Coulee Corridor 21 waShington State depaRtMent of tRanSpoRtation Mountains to Sound Greenway 25 Secretary of transportation, Paula Hammond director, highways and Local programs, Kathleen Davis Stevens Pass Greenway 29 Scenic Byways coordinator, Ed Spilker Strait of Juan de Fuca - Highway 112 33 Byway leaders and an interagency advisory group with representatives from the White Pass Scenic Byway 37 Washington State Department of Transportation, Washington State Department of Agriculture, Washington State Department of Fish & Wildlife, Washington State Tourism, Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission and State Scenic BywayS Audubon Washington were also instrumental in the creation of this guide. Cape Flattery Tribal Scenic Byway 40 puBLiShing SeRviceS pRovided By deStination -

Heritage Rail Trail Feasibility Study 2017

TOWN OF DEDHAM HERITAGE RAIL TRAIL FEASIBILITY STUDY 2017 PLANNING DEPARTMENT + ENVIRONMENTAL DEPARTMENT ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We gratefully recognize the Town of Dedham’s dedicated Planning and Environmental Department’s staff, including Richard McCarthy, Town Planner and Virginia LeClair, Environmental Coordinator, each of whom helped to guide this feasibility study effort. Their commitment to the town and its open space system will yield positive benefits to all as they seek to evaluate projects like this potential rail trail. Special thanks to the many representatives of the Town of Dedham for their commitment to evaluate the feasibility of the Heritage Rail Trail. We also thank the many community members who came out for the public and private forums to express their concerns in person. The recommendations contained in the Heritage Rail Trail Feasibility Study represent our best professional judgment and expertise tempered by the unique perspectives of each of the participants to the process. Cheri Ruane, RLA Vice President Weston & Sampson June 2017 Special thanks to: Virginia LeClair, Environmental Coordinator Richard McCarthy, Town Planner Residents of Dedham Friends of the Dedham Heritage Rail Trail Dedham Taxpayers for Responsible Spending Page | 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction and Background 2. Community Outreach and Public Process 3. Base Mapping and Existing Conditions 4. Rail Corridor Segments 5. Key Considerations 6. Preliminary Trail Alignment 7. Opinion of Probable Cost 8. Phasing and Implementation 9. Conclusion Page | 2 Introduction and Background Weston & Sampson was selected through a proposal process by the Town of Dedham to complete a Feasibility Study for a proposed Heritage Rail Trail in Dedham, Massachusetts. -

WWRP Grants 2016

Critical Habitat Projects Grants Awarded Washington Wildlife and Recreation Program 2017-2019 Project Number Grant Applicant Grant Rank Score and Type1 Project Name Grant Applicant Grant Request Match Total Awarded 1 41.90 16-1343A South Fork Manastash Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife $1,500,000 $1,500,000 $1,500,000 2 39.60 16-1333A Mid Columbia Grand Coulee Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife $3,000,000 $3,000,000 $3,000,000 3 38.10 16-1915A Mount Adams Klickitat Canyon Phase 2 Columbia Land Trust $2,440,525 $2,440,525 $4,881,050 $2,440,525 4 36.20 16-1344A Cowiche Watershed Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife $3,000,000 $3,000,000 $3,000,000 5 35.00 16-1346A Simcoe Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife $4,000,000 $4,000,000 $2,140,350 2 6 33.70 16-1699A Lehman Uplands Conservation Easement Methow Conservancy $1,134,050 $1,570,450 $2,704,500 Alternate 7 29.70 16-1325A Hoffstadt Hills Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife $3,000,000 $3,000,000 Alternate $18,074,575 $4,010,975 $22,085,550 $12,080,875 Recreation and Conservation Funding Board Resolution 2017-18 1Project Type: A=Acquisition 2P=Partial funding Critical Habitat Projects Preliminary Ranking Washington Wildlife and Recreation Program 2017-2019 Project Number and Grant Applicant Rank Score Type* Project Name Grant Applicant Request Match Total 1 41.90 16-1343A South Fork Manastash Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife $1,500,000 $1,500,000 2 39.60 16-1333A Mid Columbia Grand Coulee Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife $3,000,000 $3,000,000 -

Washington Trails Mar+Apr 2013 Wta.Org P 40 a E Trailhead

Discover Astoria & Cape Disappointment A Publication of Washington Trails Association | wta.org 20 Years of Maintaining Trails Hop on a Rail Trail Gear Going Green Mar+Apr 2013 Mar+Apr 2013 WASHINGTON TRAILS ASSOCIATION 24 16 48 Hiking with Dogs » Loren Drummond NW Explorer How to hike with your four-legged friends—from where to go, to helpful information for every dog owner. » p.24 WTA Celebrates an Anniversary! 2013 marks the 20th year of WTA's trail maintenance NW Weekend: Astoria, OR » Eli Boschetto program. Through the voices of many, we retrace its Travel down the Columbia, from Fort Vancouver to the humble beginnings with an inspired leader and a Pacific Ocean, retracing the path of Lewis & Clark. »p.28 handful of participants to its current status as a statewide Epic Trails: John Wayne » Tami Asars juggernaut with an army of trail-loving volunteers. See With more than 100 miles of trail stretching from one side how we've grown, the trails we've serviced and the of the Cascades to the other, take a hike or a ride on this friends we've made along the way! » p.16 rail trail through Snoqualmie Pass. » p.48 News+Views Trail Mix Trail Talk » Gear Closet » Gear Going Green FS Trails Coordinator Gary Paull » p.7 Top brands that reduce, reuse and recycle without compromising quality » p.32 Hiking News » Meet WTA's NW regional manager » p.8 How-To » Gear Aid Alpine Lakes Wilderness expansion bill Tips for revitalizing the water repellency of reintroduced » p.9 your jackets and boots » p.35 The new “State of Access” report » p.11 Tales from -

Lyle Falls Fish Passage Project

B O N N E V I L L E P O W E R A D M I N I S T R A T I O N Lyle Falls Fish Passage Project Draft Environmental Impact Statement DOE/EIS-0397 March 2008 Lyle Falls Fish Passage Project Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DOE/EIS-0397) Responsible Agencies: U.S. Department of Energy, Bonneville Power Administration (BPA); Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation (Yakama Nation); Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW); U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service (USFS), Title of Proposed Project: Lyle Falls Fish Passage Project State Involved: Washington (WA) Abstract: BPA proposes to fund modification of the existing Lyle Falls Fishway on the lower Klickitat River in Klickitat County, WA. The proposed project would help BPA meet its off-site mitigation responsibilities for anadromous fish affected by the development of the Federal Columbia River Power System and increase overall fish production in the Columbia Basin. The fishway is owned by WDFW and operated by the Yakama Nation. Lyle Falls prevents some upstream migrating fish from reaching the upper watershed, especially when flows are low, and the existing fishway is inefficient. BPA must decide whether to fund the project; WDFW must decide whether to approve the proposed modifications and issue a Hydraulic Project Approval; and the US Forest Service must decide whether the project is consistent with the National Wild and Scenic Rivers Act. The underlying need for the project is to improve fish passage to habitat in the upper part of the watershed. The Draft EIS evaluates the potential environmental impacts of two alternatives: No Action alternative and the Proposed Action. -

FTC Staffs Fair Booth

The mission of the Foothills Rails-to-Trails Coalition is to assist Pierce County communities in the creation and maintenance of a connected system of non-motorized trails from Mt. Rainier to Puget Sound. September 2003 The TRAIL LINE NEWS Vol. 17 No. 3 President’s message A changing of the keys Our tricky government The Foothills Rails-to-Trails Coalition has a If you have never called or written to your con- new treasurer. Stan Engle, our faithful, frugal gressman, now is a good time to start. For those of and efficient treasurer for more than 15 years you who are in the habit, we urge you to get to your has relinquished this essential responsibility to pen, phone or computer. board member Art Robinson. Art is a retired The Transportation Enhancements (TE) program is teacher who, among other qualifications, has at risk. This is the program that, with modest local ongoing experience as treasurer of a local in- matching money, has made possible in Pierce County vestment club. He was formally elected FRTTC the Foothills Trail, the Puyallup Riverwalk, the SR-16 treasurer on Thursday, July 24, after Stan had bike path, the Milton Interurban Trail, Tacoma and indicated his wish to retire from the position to Puyallup downtown Street Scape Improvements, spend more time with his wife Helen and his Bridgeport Way improvements and more. Statewide, many children and grandchildren. Washington has benefited by more than $97 million Happily, Stan intends to remain on the board, from the TE program over the past decade. This has at least for now. -

Active Transportation Plan 2020 and Beyond

WASHINGTON STATE ACTIVE TRANSPORTATION PLAN PART 1 2020 AND BEYOND ACTIVE TRANSPORTATION PLAN PART 1, 2020 AND BEYOND | CONTENTS CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................. 1 RECOMMENDATIONS ................................................................................................................................................4 NEXT STEPS ...................................................................................................................................................................4 TERMS USED IN THIS PLAN .....................................................................................................................................5 Chapter 1 CHARTING A PATH FORWARD ................................................................................................................... 7 INTRODUCTION: WE NEED A COMPASS ............................................................................................................7 PLAN CONTENTS AND ORGANIZATION .............................................................................................................9 PLAN PURPOSE ..........................................................................................................................................................10 WHY WE NEED TO PLAN FOR ACTIVE TRANSPORTATION ......................................................................11 BENEFITS OF MEASURING MULTIMODAL NETWORK CONNECTIVITY -

John Wayne Pioneer Trail Public Comments We Would Like to See The

John Wayne Pioneer Trail Public Comments We would like to see the eastern section of the John Wayne Trail kept open and NOT transferred back to adjacent land owners. Would the state consider opening this trail up to street-legal two-wheeled vehicles (a.k.a. enduro and adventure motorcycles) and snowmobiles? If bikes rode this trail regularly it would keep the weeds and grass down thus minimizing trail maintenance. It would be a shame to see this public treasure lost just because of trail use restrictions. Trails like this (and routes like the WABDR) when opened up to motorized-use bring in visitors from outside our state. It's an adventure tourist's dream to ride through land like the rolling hills of eastern WA." I am a co-founder of the non-profit Backcountry Discovery Routes based in Seattle. We would like to see the eastern section of the John Wayne Trail kept open and NOT transferred back to adjacent land owners. Would the state consider opening this trail up to street-legal two-wheeled vehicles (a.k.a. enduro and adventure motorcycles) and snowmobiles? We have created a motorcycle route across Washington north to south called the WABDR. It crosses through Ellensburg so this eastern section would come close to connecting to our route. If bikes rode this trail regularly it would keep the weeds and grass down thus minimizing trail maintenance. It would be a shame to see this public treasure lost just because of trail use restrictions. Trails like this (and routes like the WABDR) when opened up to motorized-use bring in visitors from outside our state. -

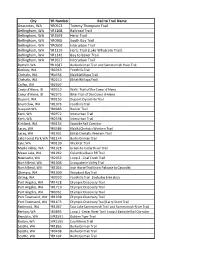

Rails to Trails Index 2020

City YR Number Rail to Trail Name Anacortes, WA YR0512 Tommy Thompson Trail Bellingham, WA YR1268 Railroad Trail Bellingham, WA YR2593 Hertz Trail Bellingham, WA YR0365 South Bay Trail Bellingham, WA YR0509 Interurban Trail Bellingham, WA YR1119 Hertz Trail (Lake Whatcom Trail) Bellingham, WA YR1142 Bay to Baker Trail Bellingham, WA YR2617 Interurban Trail Bothell, WA YR 1687 Burke Gilman Trail and Sammamish River Tral Buckley, WA YR0963 Foothills Trail Chehalis, WA YR0356 (Walk)Willapa Trail Chehalis, WA YR2210 (Bike) Willapa Trail Colfax, WA YR2307 Coeur d'Alene, ID YR0310 Walk- Trail of the Coeur d'Alene Coeur d'Alene, ID YR2075 Bike- Trail of the Coeur d-Alene Dupont, WA YR0193 Dupont Dynamite Trail Enumclaw, WA YR1076 Foothills Trail Issaquah WA YR0985 Rainier Trail Kent, WA YR0972 Interurban Trail Kent, WA YR2598 Interurban Trail Kirkland, WA YR0134 Eastside Rail Corridor Lacey, WA YR0586 (Walk) Chehalis Western Trail Lacey, WA YR1931 (Bike) Chehalis Western Trail Lake Forest Park,WA YR1144 Burke Gilman Trail Lyle, WA YR0139 Klickitat Trail Maple Valley, WA YR1328 Green-to-Cedar River Trail Moses Lake, WA YR1062 Columbia Basin RR Trail Newcastle, WA YR2052 Loop 2 - Coal Creek Trail North Bend, WA YR1008 Snoqualmie Valley Trail North Bend, WA YR1024 Iron Horse Trail (now Palouse to Cascade) Olympia, WA YR1009 Woodard Bay Trail Orting, WA YR0920 Foothills Trail (Includes bike also) Port Angeles, WA YR1428 Olympic Discovery Trail Port Angeles, WA YR1719 Olympic Discovery Trail Port Angeles, WA YR0361 Olympic Discovery Trail Port Townsend, -

Railbanking and Rail-Trails

RailbankingRailbanking And Rail-Trails A Legacy for the Future RAIL-TO-TRAILS CONSERVANCY • 1 RAILS-TO-TRAILS CONSERVANCY— creating a nationwide network of trails from former rail lines and connecting corridors to build healthier places for healthier people. On the cover: Katy Trail State Park, Missouri “One of the fascinating things about the [Katy Trail] project was that here you had the Missouri River, which is one of the most famous rivers in the United States; yet, people would drive across it on a bridge and that’s the closest they got. The Katy Trail opened up the river for people to become acquainted with.” — Columbia, Missouri, Mayor Darwin Hindman Rails-to-Trails Conservancy 1100 Seventeenth Street, NW Washington, D.C. 20036 202.331.9696 • (F) 202.331.9680 www.railstotrails.org July 2006 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY he construction and development of our rail corridors is somewhat unclear and opponents nation’s system of rail lines was nothing have challenged Congress’s authority to facilitate T short of a marvel. At its 1916 peak, more rails-to-trails conversions through railbanking. than 270,000 miles of track crisscrossed the But in 1990, the U.S. Supreme Court unani- United States, carrying freight and passengers mously upheld the Trails Act as a valid exercise of and fueling the economy and growth of a nation. Congress’s power under the Commerce Clause of the U.S. Constitution. Just as the miles of rail line peaked, however, other methods of increasingly popular transport eclipsed Through railbanking, Congress has preserved a the rail industry’s dominance.