Crossing Borders

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rencontre Hanai

COMPTE RENDU R E N C O N T R E A V E C M . H A N A Ï E T L E S C O M E D I E N S W A L I D M E Z O U A R E T S A Ï D A B O U K H A L I D Mercredi 7 février, de 11h à 13h, M. Brahim Hanaï ainsi que les comédiens Walid Mezouar et Saïd AbouKhalid ont rencontré les élèves de 2de et 1er de l’option théâtre de notre lycée. Vous trouverez ci-dessous le compte rendu que je vous propose BRAHIM HANAÏ Brahim Hanaï commence en se présentant rapidement. Il est d’abord metteur en scène et scénariste, ceci l’ayant amené par la suite à écrire quelques romans : Le balayeur en 1988, Antar en 1998. Son âme théâtrale le pousse à l’écriture de nombreuses pièces de théâtre, dont Agar des cimetières, qui fut retenu pour représenter le Maroc à la manifestation "Du monde entier" organisée par le Théâtre Gérard Philippe de Seine Saint-Denis. Après une scolarité au lycée Ibn Abbad de Marrakech, il obtient son doctorat de cinéma-théâtre à l’université de Paris VII. L’enseignant de français et dramaturge a été artiste en résidence au Mali, en France et enfin au Maroc, où il continuera d’enseigner dans de nombreuses écoles du Royaume. Enfin il est bon de rappeler qu’il fut pendant longtemps directeur artistique de la troupe régionale de Marrakech, lorsque celle-ci fut reconnue comme l’une des meilleures troupes du pays. -

Contemporary Dārija Writings in Morocco: Ideology and Practices Catherine Miller

Contemporary dārija writings in Morocco: ideology and practices Catherine Miller To cite this version: Catherine Miller. Contemporary dārija writings in Morocco: ideology and practices. Jacob Høigilt and Gunvor Mejdell The Politics of written language in the Arab world Written Changes, Brill, 2017, Studies in Semitic Languages and Linguistics, 9789004346161. halshs-01544593 HAL Id: halshs-01544593 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01544593 Submitted on 21 Jun 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Contemporary dārija writings in Morocco: ideology and practices Catherine Miller Final draft 27 01 2017 To appear in Jacob Høigilt and Gunvor Mejdell (ed) The Politics of written languages in the Arab world, Written Changes, Leiden, Brill Introduction Starting from the mid 1990s a new political, social and economical context has favored the coming out of a public discourse praising cultural and linguistic plurality as intangible parts of Moroccan identity and Moroccan heritage. The first signs of change occurred at the end of King Hassan II’s reign, setting the first steps towards political and economic liberalization. But the arrival of King Mohamed VI in 1999 definitely accelerated the trend toward economic liberalism, development of private media, emergence of a strong civil society, call for democratization and modernization, and the emergence of new urban artistic movements. -

Dynamics of Political Modernity in Lyautey's Colonial Matrix of Power

International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Analysis Volume 01 Issue 02 December 2018 Page No.- 90-97 Dynamics of Political Modernity in Lyautey’s Colonial Matrix of Power: the Rise of a Post-colonial Interweaving Performance Culture of Denial Mariem Khmiri 46, Rue Tarek Ibn Zied . 1er Etage. 3100. Kairouan. Tunisia Abstract: Things do move either because of globalization or colonialism. And as they move, they tend to acquire news identities. I would like to maintain that the movement of things, images, objects and collections accelerates the process of interweaving cultures that has started to impose itself as a principal determining factor of our cultures and identities today. In my presentation,1 I will examine the movement of French things and institutions to Morocco during colonial times as well as the impact of this movement on the Moroccan theatrical institution. For colonizers, things and institutions and objects are needful for colonization. They are also needful for implementing their civilizing missions.2I invite you to ponder with me on the following questions: why would a thing like a play be so important for colonizers? Why would colonizers need a thing like a theatrical building or a school in their colonial agenda? I argue that the movement of people alone from one place to another in order to conquer another people is always useless unless the colonizers move their things with them. It is thanks to these things that colonialism can vanquish and subjugate and achieve coloniality. Yet strikingly the colonizers’ things soon lose their colonial significance when they fall in the hands of the colonized. -

La Darija Langue « Naturelle » Du Théâtre Marocain ?

LA DARIJA LANGUE « NATURELLE » DU THÉÂTRE MAROCAIN ? Omar FERTAT* Université Bordeaux-Montaigne BIBLID [1133-8571] 26 (2019) 12.1-27. Resumen: À ses débuts le théâtre marocain, animé essentiellement par de jeunes issus des mouvements nationaliste et réformiste, adopta comme langue l’arabe classique ou littéraire. Mais très rapidement la Darija ou langue arabe marocaine, sera de plus en plus adoptée par les dramaturges marocains, jusqu’à devenir, à partir des années 1950, la langue principale du quatrième art marocain. Cet article essaiera de brosser un tableau panoramique de l’utilisation de la darija dans le théâtre marocain en s’arrêtant sur les moments les plus importants de ce processus et en mettant en lumière les expériences les plus marquantes de quelques dramaturges comme Bouchïb el Bodaoui, Abdellah Chakroun, Tayeb Al-Alj, Tayeb Saddiki, Mohamed Kaouti, qui ont non pas seulement utilisé cette langue comme moyen de communication ordinaire mais en la consacrant définitivement comme moyen d’expression artistique et littéraire. Palabras clave: Théâtre, Art, Darija, Maroc. Abstract: «Darija the ‘natural’ language of Moroccan theater?». In its beginnings the Moroccan theater, animated mainly by young people coming from the nationalist and reformist movements, adopted classical or literary Arabic as its main language. But very quickly the Darija or Moroccan Arabic, will be more and more adopted by Moroccan playwrights, until becoming, starting from the years 1950, the main language of the fourth Moroccan art. This article will draw a panoramic picture of the use of darija in Moroccan theater by considering the most important periods of this process and by highlighting the most striking experiences of some playwrights like Bouchïb el Bodaoui, Abdellah Chakroun, Tayeb Al-Alj, Tayeb Saddiki, and Mohamed Kaouti, who have not only used this linguistic variety as the language of communication but also have considered it as a means of artistic and literary expression. -

Tayeb Saddiki (1939-2016), Un Pont Entre Les Dramaturgies Arabes Et L’Occident

Horizons/Théâtre Revue d'études théâtrales 12 | 2018 Les dramaturgies arabes et l’Occident Tayeb Saddiki (1939-2016), un pont entre les dramaturgies arabes et l’Occident. Témoignage d’un entretien Angela Daiana Langone Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ht/454 DOI : 10.4000/ht.454 ISSN : 2678-5420 Éditeur Presses universitaires de Bordeaux Édition imprimée Date de publication : 1 janvier 2018 Pagination : 170-183 ISSN : 2261-4591 Référence électronique Angela Daiana Langone, « Tayeb Saddiki (1939-2016), un pont entre les dramaturgies arabes et l’Occident. Témoignage d’un entretien », Horizons/Théâtre [En ligne], 12 | 2018, mis en ligne le 01 janvier 2019, consulté le 19 juillet 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ht/454 ; DOI : 10.4000/ ht.454 La revue Horizons/Théâtre est mise à disposition selon les termes de la Licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. Angela Daiana Langone Angela Daiana Langone est chercheuse à l’Université de Cagliari (Italie), où elle enseigne la langue et la littérature arabes, ainsi que chercheuse associée à l’IREMAM de l’Université d’Aix Marseille. Elle a obtenu le Prix d’Encouragement à la Recherche 2016 décerné par l’Académie des Sciences d’Outre-mer de Paris et a publié plusieurs ouvrages concernant la littérature populaire arabe et la production écrite en arabe dialectal. Parmi ses publications, on rappellera en particulier son livre Molière et le théâtre arabe. Réception moliéresque et identités nationales arabes (Berlin, De Gruyter 2016). Mail : [email protected] RÉSUMÉ : Tayeb Saddiki (1939-2016) est et arabe littéraire) et français. -

Decolonizing Theatre History in the Arab World the Case of the Maghreb

Horizons/Théâtre Revue d'études théâtrales 12 | 2018 Les dramaturgies arabes et l’Occident Decolonizing Theatre History in the Arab World The case of the Maghreb Khalid Amine Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/ht/279 DOI: 10.4000/ht.279 ISSN: 2678-5420 Publisher Presses universitaires de Bordeaux Printed version Date of publication: 1 January 2018 Number of pages: 10-25 ISSN: 2261-4591 Electronic reference Khalid Amine, « Decolonizing Theatre History in the Arab World », Horizons/Théâtre [Online], 12 | 2018, Online since 01 January 2019, connection on 19 July 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ ht/279 ; DOI : 10.4000/ht.279 La revue Horizons/Théâtre est mise à disposition selon les termes de la Licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. Khalid Amine Professor of Performance Studies, Faculty of Letters and Humanities at Abdelmalek Essaadi University, Tetouan, Morocco, Senior Research Fellow at the Institute of Interweaving Performance Cultures, Free University, Berlin, Germany (2008-2010), and winner of the 2007 Helsinki Prize of the International Federation for Theatre Research. Since 2006, Founding President of the International Centre for Performance Studies (ICPS) in Tangier. Among his published books: Dramatic Art and the Myth of Origins: Fields of Silence (International Centre for Performance Studies Publications, 2007), Co-author with Distinguished Professor Marvin Carlson The Theatres of Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia: Performance Traditions of the Maghreb (Palgrave Series: Studies in International Performance, 2012) (edited by J. Reinelt & B. Singleton). Mail : [email protected] RÉSUMÉ : Cette contribution vise à sous- tient aussi au Maghrébins depuis la présence traire l’histoire des spectacles postcoloniaux gréco-romaine au Maghreb. -

Faouda Wa Ruina: a History of Moroccan Punk Rock and Heavy Metal Brian Kenneth Trott University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations May 2018 Faouda Wa Ruina: A History of Moroccan Punk Rock and Heavy Metal Brian Kenneth Trott University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the Islamic World and Near East History Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Trott, Brian Kenneth, "Faouda Wa Ruina: A History of Moroccan Punk Rock and Heavy Metal" (2018). Theses and Dissertations. 1934. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/1934 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FAOUDA WA RUINA: A HISTORY OF MOROCCAN PUNK ROCK AND HEAVY METAL by Brian Trott A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of a Degree of Master of Arts In History at The University of Wisconsin - Milwaukee May 2018 ABSTRACT FAOUDA WA RUINA: A HISTORY OF MOROCCAN PUNK ROCK AND HEAVY METAL by Brian Trott The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2018 Under the Supervision of Professor Gregory Carter While the punk rock and heavy metal subcultures have spread through much of the world since the 1980s, a heavy metal scene did not take shape in Morocco until the mid-1990s. There had yet to be a punk rock band there until the mid-2000s. In the following paper, I detail the rise of heavy metal in Morocco. Beginning with the early metal scene, I trace through critical moments in its growth, building up to the origins of the Moroccan punk scene and the state of those subcultures in recent years. -

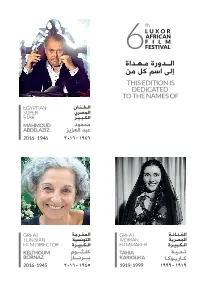

ﺍﻝــﺛﻭﺭﺓ ﻄـﻋـﺛﺍﺓ ﺇﻝﻯ ﺍﺠﻃ ﺾﻀ ﻄﻆ This Edition Is Dedicated to the Names Of

th LUXOR AFRICAN FILM 6FESTIVAL ﺍﻝــﺛﻭﺭﺓ ﻄـﻋـﺛﺍﺓ ﺇﻝﻯ ﺍﺠﻃ ﺾﻀ ﻄﻆ THIS EDITION IS DEDICATED TO THE NAMES OF ﺍﻝـﻑـﻈـﺍﻥ EGYPTIAN ﺍﻝﻡﺧﺭﻱ SUPER ﺍﻝﺿـﺊـﻐـﺭ STAR ﻄﺗﻡﻌﺩ MAHMOUD ﺲﺊﺛ ﺍﻝﺳﺞﻏﺞ ABDELAZIZ ١٩٤٦ - ٢٠١٦ 1946 - 2016 ﺍﻝﻑـﻈـﺍﻇـﺋ GREAT ﺍﻝﻡﺚـﺭﺝﺋ GREAT ﺍﻝﻡﺧﺭﻏﺋ IVORIAN ﺍﻝﺎﻌﻇﺱﻐﺋ TUNISIAN ﺍﻝـﺿـﺊﻐـﺭﺓ FILMMAKER ﺍﻝـﺿـﺊﻐـﺭﺓ FILM DIRECTOR ﺕـﺗـﻐـﺋ TAHIA ﺾﻂـﺑـــﻌﻡ KELTHOUM ﺾـﺍﺭﻏـﻌﺾـﺍ KARIOUKA ﺏـــﺭﻇـــﺍﺯ BORNAZ ١٩١٩ - ١٩٩٩ 1999 1919- ١٩٤٥ - ٢٠١٦ -1945 2016 ﺖﻂﻡﻎ ﺍﻝﻈﻡﻈﻃ ﻭﺯﻏﺭ ﺍﻝﺑﺼﺍﺸﺋ MINISTER OF CULTURE HELMY AL NAMNAM ﺗﺄﺗﻲ اﻟﺪورة اﻟﺴﺎدﺳﺔ ﻟﻬﺬا اﻟﻤﻬﺮﺟﺎن، ﻓﻲ ﻇﻞ ﻣﻨﻌﻄﻒ ﺟﺪﻳﺪ، إﻳﺠﺎﺑﻲ وﻣﻬﻢ، ﺗﺸﻬﺪه ﻣﺼﺮ، ﺣﻴﺚ ﺻﺎر اﻻﻫﺘﻤﺎم ﺑﺎﻟﺴﻴﻨﻤﺎ -ﻋﻤﻮﻣ -ﻣﻦ أوﻟﻮﻳﺎت اﻟﺤﻜﻮﻣﺔ اﻟﻤﺼﺮﻳﺔ، ارﺗﻔﻌﺖ اﻟﻤﻴﺰاﻧﻴﺔ اﻟﻤﺨﺼﺼﺔ ﻟﺼﻨﺪوق دﻋﻢ اﻟﺴﻴﻨﻤﺎ، ﻣﻦ ٢٠ ﻣﻠﻴﻮن ﺟﻨﻴﺔ إﻟﻰ ٥٠ ﻣﻠﻴﻮن ﺟﻨﻴﺔ ﺳﻨﻮﻳ، وﻳﺠﺮي اﻟﻌﻤﻞ ﺑﺠﺪﻳﺔ ﻟﺘﺄﺳﻴﺲ اﻟﺴﻴﻨﻤﺎﺗﻴﻚ، وﺗﺄﺳﻴﺲ ﺷﺮﻛﺔ ﻗﺎﺑﻀﺔ ﻟﻧﺘﺎج اﻟﺴﻴﻨﻤﺎﺋﻲ، ﻣﻤﺎ ٌﻳﺒﺸﺮ ﺑﺈزدﻫﺎر ﺣﻘﻴﻘﻲ ﻟﺼﻨﺎﻋﺔ اﻟﺴﻴﻨﻤﺎ، وﻓﻀﻼً ﻋﻦ ذﻟﻚ، ﻓﺈن ا¨ﻧﺘﺎج اﻟﺴﻴﻨﻤﺎﺋﻲ اﻟﻤﺼﺮي، ﺷﻬﺪ ﺧﻼل اﻟﻌﺎم اﻟﻤﻨﺼﺮم ارﺗﻔﺎﻋ ﻓﻲ أﻋﺪاد ا³ﻓﻼم اﻟﺘﻲ ﺗﻢ إﻧﺘﺎﺟﻬﺎ، وﺗﻤﻴﺰ· ﻓﻲ اﻟﻤﺴﺘﻮى اﻟﻔﻨﻲ. ﺗﺄﺗﻲ ﻫﺬه اﻟﺪورة -ﻛﺬﻟﻚ -ﻓﻲ ﻇﻞ اﻫﺘﻤﺎم اﻟﺪوﻟﺔ اﻟﻤﺼﺮﻳﺔ ﺑﺘﻨﺸﻴﻂ وﺗﻌﻤﻴﻖ اﻟﻌﻼﻗﺎت اﻟﻤﺼﺮﻳﺔ -ا³ﻓﺮﻳﻘﻴﺔ، ودﻋﺎ اﻟﺮﺋﻴﺲ ﻋﺒﺪ اﻟﻔﺘﺎح اﻟﺴﻴﺴﻲ ﻓﻲ ﻧﻬﺎﻳﺔ ﻣﺆﺗﻤﺮ أﺳﻮان ﻟﻠﺸﺒﺎب، إﻟﻰ إﻋﺪاد أﺳﻮان ﻟﺘﻜﻮن ﻋﺎﺻﻤﺔ ﻟﻗﺘﺼﺎد واﻟﺜﻘﺎﻓﺔ ا¨ﻓﺮﻳﻘﻴﺔ. وأﺧﻴﺮ·، ﺗﺘﻮاﻓﻖ ﻫﺬه اﻟﺪورة ﻣﻦ اﻟﻤﻬﺮﺟﺎن، ﻣﻊ اﻻﺣﺘﻔﺎل ﺑﺎ³ﻗﺼﺮ ﻋﺎﺻﻤﺔ ﻟﻠﺜﻘﺎﻓﺔ اﻟﻌﺮﺑﻴﺔ، ﻃﻮال ﻫﺬا اﻟﻌﺎم، ﻛﺎﻧﺖ ا³ﻗﺼﺮ داﺋﻤ ﻧﻘﻄﺔ اﻟﺘﻘﺎء ﺑﻴﻦ اﻟﺤﻀﺎرﺗﻴﻦ اﻟﻤﺼﺮﻳﺔ اﻟﻘﺪﻳﻤﺔ (اﻟﻔﺮﻋﻮﻧﻴﺔ) واﻟﺤﻀﺎرة اﻟﻌﺮﺑﻴﺔ – ا¨ﺳﻼﻣﻴﺔ، واﺧﺘﻴﺎر ا³ﻗﺼﺮ ﻋﺎﺻﻤﺔ ﻟﻠﺜﻘﺎﻓﺔ اﻟﻌﺮﺑﻴﺔ، ﻳﺆﻛﺪ ﻋﻠﻰ ﻫﺬا ٌاﻟﺒﻌﺪ. The sixth edition of Luxor African Film Festival comes within the shadow of a new positive and significant turn that Egypt is witnessing of paying a special attention to cinema and being one of the priorities of the Egyptian government as the budget of the cinema fund has increased from 20 million EGP to 50 million EGP annually, while tireless efforts are made to found Cimatheque and founding a company for cinema production that promises a rich cinema production in addition to the increase of the number of produced films last year and of a good quality. -

Angela Daiana Langone Molière Et Le Théâtre Arabe Mimesis

Angela Daiana Langone Molière et le théâtre arabe Mimesis Romanische Literaturen der Welt Herausgegeben von Ottmar Ette Band 62 Angela Daiana Langone Molière et le théâtre arabe Réception moliéresque et identités nationales arabes Università degli Studi di Cagliari – Dipartimento di Filologia, Letteratura, Linguistica – Pubblicazione realizzata con il contributo dei fondi CAR ex-60%. ISBN 978-3-11-044234-2 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-043684-6 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-043445-3 ISSN 0178-7489 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.dnb.de abrufbar. © 2016 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Druck und Bindung: CPI books GmbH, Leck ♾ Printed on acid-free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Table des matières Avant-propos � IX Systèmes de transcription de l’arabe � XI Transcription de l’arabe classique � XI Transcription de l’arabe dialectal � XII 1 Introduction � 1 1.1 Un Molière arabe � 1 1.2 Le cadre théorique � 9 1.3 Le théâtre arabe et l’évolution de la pensée nationale � 11 1.4 La structure de la recherche � 14 2 Sortir de la stagnation � 21 2.1 La première expérience dramaturgique du monde arabe � 21 2.2 L’expérience de Mārūn Naqqāš � 25 2.2.1 La biographie � 25 2.2.2 La troupe de Mārūn Naqqāš � 28 2.2.3 Le lieu de -

Comment Épargner Le Chaos Urbain Et Le Chaos Mental Aux Citadinsp. 16

PREVENTICA FENELEC: Une CHINA TRADE MAROC: 3 jours pour mission d’affaires WEEK (CTW) Maroc se former, s’informer, à Nouakchott du 2018: Des produits rencontrer des experts en 09 au 13 décembre et services chinois de un lieu unique P. 6 2018 P. 10 haute qualité. P. 26 N° 73 - Décembre 2018 - 50 Dh / 5 € Comment épargner le chaos urbain et le chaos mental aux citadins P. 16 offre à la fois Conseil, Accompagnement et Subventions qui peuvent atteindre 200 000 Abdellatif Lyoubi Idrissi, Directeur Général du GIAC/BTP DH par entreprise P. 12 EDITO Les puissants de la finance Jamal KORCH mondiale reprennent le pouvoir de gouverner à la place des politiciens e régime démocratique n’était qu’un jeu élec- Puisque les vrais commandants de bord et les toral, et ce depuis des décennies. Le politicien pilotes des différentes politiques exercées dans tous les exprime à son adversaire de l’opposition sa pays du monde sont autres que ceux qui sont élus et qui gratitude et son amitié, mais aussi sa rivalité se médiatisent régulièrement. Les vrais gouvernants sont exigée dans le cadre de son métier de politicien à l’inté- à l’abri et tirent les ficelles à partir de leurs conclaves Lrieur de l’institution parlementaire. Cette ambivalence confidentiels. repérée dans le métier de politicien n’est plus tolérable aujourd’hui, à cause de l’instauration du nouveau régime Cependant, ces hommes puissants de la planète, politique, qui est le nouvel ordre mondial ou l’ordre inter- forts par la discrétion et le retenu, sortent de leur cachète national libéral. -

Moroccan Trilogy. 1950-2020

MOROCCAN TRILOGY. 1950-2020 DATES: March 30, 2021 – September 27, 2021 LOCATION: Museo Reina Sofía (Madrid). Sabatini Building, 3rd floor ORGANIZATION: An initiative of: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Ministry of Culture and Sport of the Government of Spain, and National Foundation of Museums of the Kingdom of Morocco With the collaboration of: Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art – Qatar Museums and Qatar Foundation CURATORSHIP: Manuel Borja-Villel and Abdellah Karroum COORDINATION: Leticia Sastre Moroccan Trilogy 1950-2020 articulates a visual dialogue that reflects artistic production at three historical moments from independence to the present day. It does so through a significant selection of artworks that show the diversity of initiatives, the vitality of artistic debate and the interdisciplinary exchanges to be found in Morocco. This exhibition falls within the area of decolonial research, one of the central focuses of the Museum’s programming. It is a first attempt to broaden the focus of these analyses by turning the gaze onto the southern shore of the Mediterranean, the cradle of western civilization, and more specifically onto Morocco, an ancient country just 14 kilometers away from Spain. The show has been organized within the framework of the program for cultural cooperation between Spain and Morocco in the field of Museums, an initiative fostered by the National Foundation of Museums of the Kingdom of Morocco and the Ministry of Culture and Sport of the Government of Spain, in collaboration with Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art in Qatar. Moroccan Trilogy 1950- 2020 offers an account of artistic experiences in Morocco from the mid-20th century onwards, focusing particularly on the three urban centers of Tétouan, Casablanca and Tangier. -

Introduction Part I the Pre-Colonial Maghreb

Notes Introduction 1. Routledge World Encyclopedia of Contemporary Drama, Volume 4, ed. Don Rubin (London: Routledge, 1999). 2. For example, M. M. Badawi: Modern Arabic Drama in Egyptt (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987), Early Arabic Drama (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988); Philip Sadgrove: The Egyptian Theatre in the Nineteenth Centuryy (Durham: University of Durham Press, n.d.). 3. Salma Jayyusi and Roger Allen (eds), Arabic Writing Today: The Drama (Cairo: American Research Center, 1977); Salma Jayyusi and Roger Allen (eds), Modern Arabic Drama (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1995); Salma Jayyusi (ed.), Short Arabic Plays (London: Interlink, 2003). 4. Taher Bekri, De la literature tunisienne et maghrébin (Paris: Harmattan, 1999). All translations from French and Arabic sources are by the authors, unless otherwise noted. 5. Ibid., 5–13. 6. M. M. Badawi, “Arabic Drama Since the Thirties,” in Modern Arabic Literature (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 402. 7. The only book-length study of drama in the Maghreb in English is the highly informative, but rather narrowly focused Strategies of Resistance in the Dramatic Texts of North African Women Dramatists by Laura Chakravarty Box (London: Taylor & Francis, 2004). The only English-language collection of drama from this region yet to appear is Four Plays from North Africa, ed. Marvin Carlson (New York: Martin E. Segal, 2008). 8. M. Flangon Rogo Koffi, Le Théâtre Africain Francophone (Paris: Harmattan, 2002). Part I The Pre-Colonial Maghreb Chapter 1 The Roman Maghreb 1. Michael Brett and Elizabeth Fentress, The Berbers (Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, 1996), 50. 2. Trudy Ring, Adele Hast and Paul Challenger, International Dictionary of Historic Places.