Roman Scotland, the Tribes of Ancient Scotland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Celticism, Internationalism and Scottish Identity Three Key Images in Focus

Celticism, Internationalism and Scottish Identity Three Key Images in Focus Frances Fowle The Scottish Celtic Revival emerged from long-standing debates around language and the concept of a Celtic race, a notion fostered above all by the poet and critic Matthew Arnold.1 It took the form of a pan-Celtic, rather than a purely Scottish revival, whereby Scotland participated in a shared national mythology that spilled into and overlapped with Irish, Welsh, Manx, Breton and Cornish legend. Some historians portrayed the Celts – the original Scottish settlers – as pagan and feckless; others regarded them as creative and honorable, an antidote to the Industrial Revolution. ‘In a prosaic and utilitarian age,’ wrote one commentator, ‘the idealism of the Celt is an ennobling and uplifting influence both on literature and life.’2 The revival was championed in Edinburgh by the biologist, sociologist and utopian visionary Patrick Geddes (1854–1932), who, in 1895, produced the first edition of his avant-garde journal The Evergreen: a Northern Seasonal, edited by William Sharp (1855–1905) and published in four ‘seasonal’ volumes, in 1895– 86.3 The journal included translations of Breton and Irish legends and the poetry and writings of Fiona Macleod, Sharp’s Celtic alter ego. The cover was designed by Charles Hodge Mackie (1862– 1920) and it was emblazoned with a Celtic Tree of Life. Among 1 On Arnold see, for example, Murray Pittock, Celtic Identity and the Brit the many contributors were Sharp himself and the artist John ish Image (Manchester: Manches- ter University Press, 1999), 64–69 Duncan (1866–1945), who produced some of the key images of 2 Anon, ‘Pan-Celtic Congress’, The the Scottish Celtic Revival. -

THE MYTHOLOGY, TRADITIONS and HISTORY of Macdhubhsith

THE MYTHOLOGY, TRADITIONS and HISTORY OF MacDHUBHSITH ― MacDUFFIE CLAN (McAfie, McDuffie, MacFie, MacPhee, Duffy, etc.) VOLUME 2 THE LANDS OF OUR FATHERS PART 2 Earle Douglas MacPhee (1894 - 1982) M.M., M.A., M.Educ., LL.D., D.U.C., D.C.L. Emeritus Dean University of British Columbia This 2009 electronic edition Volume 2 is a scan of the 1975 Volume VII. Dr. MacPhee created Volume VII when he added supplemental data and errata to the original 1792 Volume II. This electronic edition has been amended for the errata noted by Dr. MacPhee. - i - THE LIVES OF OUR FATHERS PREFACE TO VOLUME II In Volume I the author has established the surnames of most of our Clan and has proposed the sources of the peculiar name by which our Gaelic compatriots defined us. In this examination we have examined alternate progenitors of the family. Any reader of Scottish history realizes that Highlanders like to move and like to set up small groups of people in which they can become heads of families or chieftains. This was true in Colonsay and there were almost a dozen areas in Scotland where the clansman and his children regard one of these as 'home'. The writer has tried to define the nature of these homes, and to study their growth. It will take some years to organize comparative material and we have indicated in Chapter III the areas which should require research. In Chapter IV the writer has prepared a list of possible chiefs of the clan over a thousand years. The books on our Clan give very little information on these chiefs but the writer has recorded some probable comments on his chiefship. -

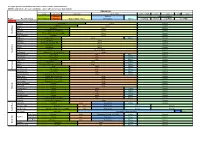

A Very Rough Guide to the Main DNA Sources of the Counties of The

A Very Rough Guide To the Main DNA Sources of the Counties of the British Isles (NB This only includes the major contributors - others will have had more limited input) TIMELINE (AD) ? - 43 43 - c410 c410 - 878 c878 - 1066 1066 -> c1086 1169 1283 -> c1289 1290 (limited) (limited) Normans (limited) Region Pre 1974 County Ancient Britons Romans Angles / Saxon / Jutes Norwegians Danes conq Engl inv Irel conq Wales Isle of Man ENGLAND Cornwall Dumnonii Saxon Norman Devon Dumnonii Saxon Norman Dorset Durotriges Saxon Norman Somerset Durotriges (S), Belgae (N) Saxon Norman South West South Wiltshire Belgae (S&W), Atrebates (N&E) Saxon Norman Gloucestershire Dobunni Saxon Norman Middlesex Catuvellauni Saxon Danes Norman Berkshire Atrebates Saxon Norman Hampshire Belgae (S), Atrebates (N) Saxon Norman Surrey Regnenses Saxon Norman Sussex Regnenses Saxon Norman Kent Canti Jute then Saxon Norman South East South Oxfordshire Dobunni (W), Catuvellauni (E) Angle Norman Buckinghamshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Bedfordshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Hertfordshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Essex Trinovantes Saxon Danes Norman Suffolk Trinovantes (S & mid), Iceni (N) Angle Danes Norman Norfolk Iceni Angle Danes Norman East Anglia East Cambridgeshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Huntingdonshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Northamptonshire Catuvellauni (S), Coritani (N) Angle Danes Norman Warwickshire Coritani (E), Cornovii (W) Angle Norman Worcestershire Dobunni (S), Cornovii (N) Angle Norman Herefordshire Dobunni (S), Cornovii -

The Great Migration: DNA Testing Companies Allow Us to Answer The

We Scots Are All Immigrants – And Cousins to Boot! by John King Bellassai * [This article appears in abbreviated form in the current issue of Scots Heritage Magazine. It is reprinted here in its entirety with the permission of the editors of that publication.] America is a nation of immigrants. In fact, North America was uninhabited until incomers from Asia crossed a land bridge from Siberia to Alaska some 12,000 years ago—right after the last Ice Age—to eventually spread across the continent. In addition, recent evidence suggests that at about the same time, other incomers arrived in South America by boat from Polynesia and points in Southeast Asia, spreading up the west coast of the contingent. Which means the ancestors of everyone here in the Americas, everyone who has ever been here, came from somewhere else. Less well known is the fact that Britain, too, has been from the start a land of immigrants. In recent years geology, climatology, paleo-archaeology, and genetic population research have come together to demonstrate the hidden history of prehistoric Britain—something far different than what was traditionally believed and taught in schools. We now know that no peoples were indigenous to Britain. True, traces of humanoids there go back 800,000 years (the so-called Happisburg footprints), and modern humans (Cro-Magnon Man) did indeed inhabit Britain about 40,000 years ago. But we also now know that no one alive today in Britain descends from these people. Rather, during the last Ice Age, Britain, like the rest of Northern Europe, was uninhabited—and uninhabitable. -

Galloway-Glens-All-Combined.Pdf

000 600 000 590 000 580 000 570 000 560 000 550 KEY GGLP boundary Mesolithic sites 000 240000 250000 260000 270000 280000 540 Figure 4: Mesolithic elements of the historic environment Drawn by: O Lelong, 10.8.2017 ± Map scale @ A3: 1:175,000 000 600 000 590 000 580 000 570 000 560 KEY GGLP boundary Burnt mound 000 Cairn 550 Cup and ring marks Hut circle Standing stone Stone circle 000 240000 250000 260000 270000 280000 540 Figure 5: Neolithic to early BA elements of the historic environment Drawn by: O Lelong, 10.8.2017 ± Map scale @ A3: 1:175,000 000 600 000 590 000 580 000 570 000 560 000 550 KEY GGLP boundary Axehead, axe hammer (stone) Axehead, palstave, dirks etc (bronze) 000 240000 250000 260000 270000 280000 540 Figure 6: Find-spots of Bronze Age metalwork and battle axes Drawn by: O Lelong, 10.8.2017 ± Map scale @ A3: 1:175,000 000 600 000 590 000 580 000 570 000 560 KEY 000 GGLP boundary 550 Dun Fort Possible fort Settlement 000 240000 250000 260000 270000 280000 540 Figure 7: Late Bronze Age to Iron Age elements of the historic environment Drawn by: O Lelong, 10.8.2017 ± Map scale @ A3: 1:175,000 000 600 000 590 000 580 000 570 000 560 KEY 000 GGLP boundary 550 Enclosure Find-spot Fort annexe Temporary camp 000 240000 250000 260000 270000 280000 540 Figure 8: Roman elements of the historic environment Drawn by: O Lelong, 10.8.2017 ± Map scale @ A3: 1:175,000 000 600 000 590 000 580 000 570 000 560 KEY GGLP boundary Abbey 000 Castle or tower house 550 Church, chapel or cemetery Motte Settlement Well 000 240000 250000 260000 270000 -

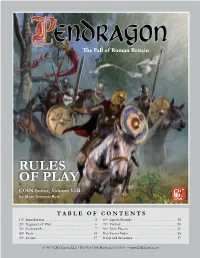

RULES of PLAY COIN Series, Volume VIII by Marc Gouyon-Rety

The Fall of Roman Britain RULES OF PLAY COIN Series, Volume VIII by Marc Gouyon-Rety T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S 1.0 Introduction ............................2 6.0 Epoch Rounds .........................18 2.0 Sequence of Play ........................6 7.0 Victory ...............................20 3.0 Commands .............................7 8.0 Non-Players ...........................21 4.0 Feats .................................14 Key Terms Index ...........................35 5.0 Events ................................17 Setup and Scenarios.. 37 © 2017 GMT Games LLC • P.O. Box 1308, Hanford, CA 93232 • www.GMTGames.com 2 Pendragon ~ Rules of Play • 58 Stronghold “castles” (10 red [Forts], 15 light blue [Towns], 15 medium blue [Hillforts], 6 green [Scotti Settlements], 12 black [Saxon Settlements]) (1.4) • Eight Faction round cylinders (2 red, 2 blue, 2 green, 2 black; 1.8, 2.2) • 12 pawns (1 red, 1 blue, 6 white, 4 gray; 1.9, 3.1.1) 1.0 Introduction • A sheet of markers • Four Faction player aid foldouts (3.0. 4.0, 7.0) Pendragon is a board game about the fall of the Roman Diocese • Two Epoch and Battles sheets (2.0, 3.6, 6.0) of Britain, from the first large-scale raids of Irish, Pict, and Saxon raiders to the establishment of successor kingdoms, both • A Non-Player Guidelines Summary and Battle Tactics sheet Celtic and Germanic. It adapts GMT Games’ “COIN Series” (8.1-.4, 8.4.2) game system about asymmetrical conflicts to depict the political, • A Non-Player Event Instructions foldout (8.2.1) military, religious, and economic affairs of 5th Century Britain. -

Annals of the Caledonians, Picts and Scots

Columbia (HnitJer^ftp intlifCttpufUmigdrk LIBRARY COL.COLL. LIBRARY. N.YORK. Annals of t{ie CaleDoiuans. : ; I^col.coll; ^UMl^v iV.YORK OF THE CALEDONIANS, PICTS, AND SCOTS AND OF STRATHCLYDE, CUMBERLAND, GALLOWAY, AND MURRAY. BY JOSEPH RITSON, ESQ. VOLUME THE FIRST. Antiquam exquirite matrem. EDINBURGH PRINTED FOR W. AND D. LAING ; AND PAYNE AND FOSS, PALL-MALL, LONDON. 1828. : r.DiKBURnii FIlINTEn I5Y BAI.LANTTNK ASn COMPAKV, Piiiri.'S WOKK, CANONGATK. CONTENTS. VOL. I. PAGE. Advertisement, 1 Annals of the Caledonians. Introduction, 7 Annals, -. 25 Annals of the Picts. Introduction, 71 Annals, 135 Appendix. No. I. Names and succession of the Pictish kings, .... 254 No. II. Annals of the Cruthens or Irish Picts, 258 /» ('^ v^: n ,^ '"1 v> Another posthumous work of the late Mr Rlt- son is now presented to the world, which the edi- tor trusts will not be found less valuable than the publications preceding it. Lord Hailes professes to commence his interest- ing Annals with the accession of Malcolm III., '* be- cause the History of Scotland, previous to that pe- riod, is involved in obscurity and fable :" the praise of indefatigable industry and research cannot there- fore be justly denied to the compiler of the present volumes, who has extended the supposed limit of authentic history for many centuries, and whose labours, in fact, end where those of his predecessor hegi7i. The editor deems it a conscientious duty to give the authors materials in their original shape, " un- mixed with baser matter ;" which will account for, and, it is hoped, excuse, the trifling repetition and omissions that sometimes occur. -

Art. IIL—The PEOPLES of ANCIENT SCOTLAND

(60) Art. IIL—the PEOPLES OF ANCIENT SCOTLAND. Being the Fourth Rhind Lecture. this lecture it is proposed to make an attempt to under- IN stand the position of the chief peoples beyond the Forth at the dawn of the history of this country, and to follow that down sketchil}' to the organization of the kingdom of Alban. This last part of the task is not undertaken for its own sake, or for the sake of writing on the history of Scotland, which has been so ably handled by Dr. Skene and other historians, of whom you are justly proud, but for the sake of obtaining a comprehensive view of the facts which that history offers as the means of elucidating tlie previous state of things. The initial difficulty is to discover just a few fixed points for our triangulation so to say. This is especially hard to do on the ground of history, so I would try first the geography of the here obtain as our data the situation country ; and we of the river Clyde and the Firth of Forth, then that of the Grampian ]\Iountains and the Mounth or the high lands, extending across the country from Ben Nevis towards Aberdeen. Coming now more to historical data, one may mention, as a fairly well- defined fact, the position of the Koman vallum between the Firth of Forth and the Clyde, coinciding probably with the line of forts erected there in the 81 it by Agricola year ; and is probably the construction of this vallum that is to be understood by the statements relative to Severus building a wall across the island. -

A Guide to Ten of the Best Pictish Symbol Stones in Aberdeenshire

Pictish Symbol Stones The Pictish Period 300 AD – 900 AD MAIDEN STONE ST PETER’S CHURCH, FYVIE As one of the heartlands of the Pictish community, Aberdeenshire is home to a large The origin of the Picts can be found in the tribal society of the Iron Age. Their society was number of the elaborately decorated Symbol Stones for which the Picts are famed – around hierarchical, with a warrior elite and a lower farming class. They lived in Scotland, North of PICARDY STONE 20% of all Pictish stones recorded in Scotland can be found in Aberdeenshire. the Forth and Clyde rivers, between the 4th and 9th Centuries AD, with a particularly strong presence in what is now Aberdeenshire. This can be seen in the frequent occurrence of place The stones, incised or carved in relief, are decorated with a variety of symbols, ranging from names beginning “Pit”, thought to indicate the site of a Pictish settlement, as well as the BRANDSBUTT geometric shapes and patterns, to animals (real and mythical), human figures, objects, evidence from the archaeological record such as Symbol Stones and fortifications. and Christian motifs. Some earlier Pictish stones are also incised with a script known as Ogham, which comprises a pattern of short linear strokes crossing a vertical line. Said to They acquired the name Pict, or Picti, meaning “Painted People”, from the Romans – indeed, have originated around the 4th Century AD, it is an early form of the Irish language. Most much of what is known of the Picts is derived from historical writers from outside of examples of Ogham inscriptions are thought to represent personal names. -

Now the War Is Over

Pollard, T. and Banks, I. (2010) Now the wars are over: The past, present and future of Scottish battlefields. International Journal of Historical Archaeology,14 (3). pp. 414-441. ISSN 1092-7697. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/45069/ Deposited on: 17 November 2010 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk Now the Wars are Over: the past, present and future of Scottish battlefields Tony Pollard and Iain Banks1 Suggested running head: The past, present and future of Scottish battlefields Centre for Battlefield Archaeology University of Glasgow The Gregory Building Lilybank Gardens Glasgow G12 8QQ United Kingdom Tel: +44 (0)141 330 5541 Fax: +44 (0)141 330 3863 Email: [email protected] 1 Centre for Battlefield Archaeology, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, Scotland 1 Abstract Battlefield archaeology has provided a new way of appreciating historic battlefields. This paper provides a summary of the long history of warfare and conflict in Scotland which has given rise to a large number of battlefield sites. Recent moves to highlight the archaeological importance of these sites, in the form of Historic Scotland’s Battlefields Inventory are discussed, along with some of the problems associated with the preservation and management of these important cultural sites. 2 Keywords Battlefields; Conflict Archaeology; Management 3 Introduction Battlefield archaeology is a relatively recent development within the field of historical archaeology, which, in the UK at least, has itself not long been established within the archaeological mainstream. Within the present context it is noteworthy that Scotland has played an important role in this process, with the first international conference devoted to battlefield archaeology taking place at the University of Glasgow in 2000 (Freeman and Pollard, 2001). -

MONS GRAUPIUS Alternative Names: None Late 83 Or 84 CE Date Published: July 2016 Date of Last Update to Report: N/A

Inventory of Historic Battlefields Research report This battle was researched and assessed against the criteria for inclusion on the Inventory of Historic Battlefields set out in Historic Environment Scotland Policy Statement June 2016 https://www.historicenvironment.scot/advice-and- support/planning-and-guidance/legislation-and-guidance/historic-environment- scotland-policy-statement/. The results of this research are presented in this report. The site does not meet the criteria at the current time as outlined below (see reason for exclusion). MONS GRAUPIUS Alternative Names: None Late 83 or 84 CE Date published: July 2016 Date of last update to report: N/a Overview The Battle of Mons Graupius is the best documented engagement between the Roman forces, stationed in southern Britannia, and the Caledonian tribes of the northern part of the island. It marked the culmination of multiple years of campaigning by the Roman governor of the province, Gnaeus Julius Agricola, against the “barbarian” tribes and he inflicted a resounding defeat on the confederacy of Caledonians arrayed against him. Much of what is known about the battle is contained within the Agricola, written in 97-98 CE by Agricola’s son in law, the Roman historian Tacitus. This is a heavily biased and only partially surviving account which amounts to a veneration of Agricola. There are no indigenous accounts of the battle and no archaeological evidence has been confirmed as connected to the conflict. Although the site has drawn attention from academics since antiquarian times, the precise date, location and the vast majority of details of the engagement remain unconfirmed. Reason for exclusion There is no certainty about the location of the battle, and there are also significant questions about the accuracy of the accounts describing it. -

History 3 4 Pages on Hadrian's Wall

We visit and photograph good bed and breakfasts, hotels and self catering cottages in Scotland History 3 4 pages on Hadrian's Wall Find on maps: Bed and Breakfast & Hotels Edinburgh Accommodation Wedding & Party One of the greatest monuments to the power Venues - and limitations - of the Roman Empire, Self-catering Rental Cottages Hadrian's Wall ran for 73 miles across open country. Touring Routes around Scotland Why was it built? Find on lists: At the time of Julius Caesar's first small invasion of the south Bed and Breakfast coast of Britain in 55 BC, the British Isles, like much of mainland & Hotels Europe was inhabited by many Celtic tribes loosely united by a Hotel similar language and culture but nevertheless each distinct. He Accommodation returned the next year and encountered the 4000 war chariots of the Catevellauni in a land "protected by forests and marshes, Edinburgh Accommodation and filled with a great number of men and cattle." He defeated the Catevellauni and then withdrew, though not before Wedding & Party establishing treaties and alliances. Thus began the Roman occupation of Britain. Venues Nearly 100 years later, in 43 AD, the Emperor Claudius sent Aulus Plautius and about 24,000 soldiers to Britain, Self-catering Rental Cottages this time to establish control under a military presence. Although subjugation of southern Britain proceeded fairly smoothly by a combination of military might and clever diplomacy, and by 79 AD what is now England and Wales What to do, were firmly under control, the far North remained a problem. However, the Emperor Vespasian decided that what is walking, riding..