Galloway-Glens-All-Combined.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

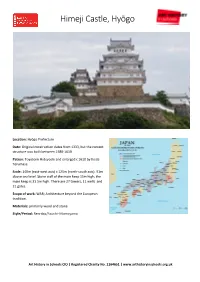

Himeji Castle, Hyōgo

Himeji Castle, Hyōgo Location: Hyōgo Prefecture Date: Original construction dates from 1333, but the current structure was built between 1580-1610 Patron: Toyotomi Hideyoshi and enlarged c 1610 by Ikeda Terumasa. Scale: 140m (east-west axis) x 125m (north-south axis). 91m above sea level. Stone wall of the main keep 15m high; the main keep is 31.5m high. There are 27 towers, 11 wells and 21 gates. Scope of work: WAR; Architecture beyond the European tradition. Materials: primarily wood and stone Style/Period: Renritsu/Azuchi–Momoyama Art History in Schools CIO | Registered Charity No. 1164651 | www.arthistoryinschools.org.uk Himeji Castle, Hyōgo Introduction Japan’s most magnificent castle, a Unesco World Heritage Site and one of only a handful of original castles remaining. Nicknamed the ‘White Egret Castle’ for its spectacular white exterior and striking shape emerging from the plain. Himeji is a hill castle, that takes advantage of the surrounding geography to enhance its defensive qualities. There are three moats to obstruct the enemy and 15m sloping stone walls make approaching the base of the castle very difficult. Formal elements Viewed externally, there is a five-storey main tenshu (keep) and three smaller keeps, all surrounded by moats and defensive walls. These walls are punctuated with rectangular openings (‘sama’) for firing arrows and circular and triangular openings for guns. These ‘sama’ are at different heights to allow for the warrior to be standing, kneeling or lying down. The main keep’s walls also feature narrow openings that allowed defenders to pour boiling water or oil on to anyone trying to scale the walls. -

Christ Church, Dalbeattie

Scottish Episcopal Church Diocese of Glasgow & Galloway Christ Church, Dalbeattie Mothering Sunday posy o Issue N 21 March 2017 Who’s Who at Christ Church Priest-in-Charge Revd Canon David Bayne 01556 503818 Honorary Assistant Priest Revd Mark RS Smith 01387 760263 NSM Revd Beryl Scott 01556 610283 Lay Representative/ Mrs. Edith Thorp 01556 610816 Munches Park Coordinator Alternate Lay Representative Mr Alfred Thorp 01556 610816 Honorary Musical Director Mrs Maggie Kelt & Organist Honorary Secretary Mrs Sue Thomas 01556 612863 Treasurer Mr Mark Parry Gift Aid/Free Offering Mr Alfred Thorp 01556 610816 Recorder (envelopes) Rector’s Warden & Health & Dr Keith Dennison 01556 630413 Safety Coordinator People’s Warden Mr. George Sims 01556 612069 Protection of Vulnerable Mrs Helen Stephens 01556 610627 Groups Co-ordinator Vestry Members Rector’s Warden (Lay Chair) 01556 630413 Lay Representative 01556 610816 Alternate Lay Representative 01556 610816 People’s Warden 01556 612069 Constituent Vestry Members Mrs Robin Charlton 01556 630265 Mr Anthony Duncalf 01556 612322 Mrs Llyn Glendinning 01556 610676 Mr Ron Newton 01556 611567 Mrs Helen Stephens 01556 610627 Mrs Sue Thomas 01556 612863 Vacancy Property Working Group Canon David Bayne, Dr Keith Dennison, Mrs Sue Thomas and Mr Alfred Thorp Bible Reading Fellowship Dr Keith Dennison 01556 630413 Brass & Vestry Cleaning Group Mrs Robin Charlton 01556 630265 Chat & Craft Group Mrs Jane Greenwood 01556 611144 Church Flowers Coordinator Mrs Julie Dennison 01556 630413 Gardening Coordinator Mrs Julie Dennison 01556 630413 Hard of Hearing Clinic Coordinator Mrs Jenny Edkins 01556 611740 Magazine Team Mrs Miranda Brignall 01556 610409 Mrs Muriel Palmer 01556 630314 Mr Ron Newton 01556 611567 Mission to Seafarers Contact Mrs Muriel Palmer 01556 630314 Reader Coordinator Mrs Julie Dennison 01556 630413 Bishop Gregor continues to recover at home. -

Based on Parish Lists of Wigtownshire and Minnigaff Scottish Records Society No

A CENSUS OF AGNEWS IN WIGTOWNSHIRE 1684 Based on Parish Lists of Wigtownshire and Minnigaff Scottish Records Society No. 50 PARISH DIVISION AGNEW ASSOCIATED NAME RELATIONSHIP NOTES GIVEN NAME GLASSERTON Craichdo u Grizell Agnew Patrick Christian Spouse Probable (Craigdow) GLENLUCE Drumeen Thomas Agnew Janet McIlroy Spouse Probable (Old Luce) Kirk -Toune Robe rt Agnew Marg. McDouall Spouse Probable INCH Little John Agnew Bessie Bigham spouse Colreoch farm John Agnew Son Janet Agnew John Heron Possible Sp Daughter? Kilmenoch Mary Agnew John Adair Spous e John Adair fined £ 600 by Episcopalian Council Son of Andrew Adair of Little Genoch (Kirmennoch) farm Little Genoch Andrew Agnew Widower? Father of Mary at Kilmenoch Helen Agnew Robert Adair Spouse Daughter of Andrew Agnew next above s/ Andrew Adair of Little Genoch 1 PARISH DIVISION AGNEW ASSOCIATED NAME RELATIONSHIP NOTES GIVEN NAME Seat of Agnew family of Sheuchan See Parish of INCH Sheuchan CONT’D Leswalt Dalmanoch John Agnew John Guthrick & Anna Servant to (Dalmennoch) Vaux Clada House Alexander Agnew Florence Stewart Spouse Croch Jonet Agnew Gilbert McWilliam Spouse (Croech, later Lochryan) Milne of Larg Agnes Agnew Servant ? KIRKCOLM Kurckeume Jannet Agn new John McMeikin Spouse ? (KirkcolmVillage) Thomas Agnew Patrick Aginew, younger Jannet Agnnew James McCaige Spouse? Clanrie Andro (head ) a farm (Clendry) Aginew (sic) Thomas Janet Cambell Spouse ? Prob son of Andro Aginew (sic) John Agnew John Agnew, younger Marget Aginew Marget Agnew younger 2 PARISH DIVISION AGNEW ASSOCIATED -

CYCLING Stewartry

CYCLING in and around Stewartry The natural place to cycle See also:- - Cycling Signposted Routes in Dumfries and Galloway - Sustrans Maps www.sustrans.org.uk - The National Byway Map www.thenationalbyway.org.uk Particular thanks to John Taylor CTC for route and text contributions and for photographs. Photographs also by Alan Devlin and Dumfries and Galloway Tourist Board This publication has been, designed and funded by a partnership of: Supported by Solway Heritage through the Landfill Tax Credit Scheme A Message from the Health Improvement Group Cycling can seriously improve your health & happiness. Enjoy! CYCLING IN STEWARTRY This booklet is one of a series of four covering the whole of Dumfries & Galloway that suggest a variety of cycle tours for visitors and locals of all abilities. Local cycling enthusiasts, using their knowledge of the quieter roads, cycle routes and byways, have researched the routes to provide an interesting and rewarding taste of the region. A note of distance, time, terrain and facilities is given at the start of each route. All start points offer parking, toilets, snack places and accommodation. Some routes include stretches off-tarmac and this is indicated at the start of the route. Parking discs are required for some car parks and these are available at Tourist Information Centres and in local shops. Stewartry is part of the old province of Galloway. In those centuries when the easiest way to travel any distance was by sea, it held a strategic place on the west coast, Irish and Isle of Man routes. This explains the many archaeological remains near the coast. -

Viking River Cruises 2018

VIKING RIVER CRUISES 2018 River Cruise Atlas Brochure 2018.indd 1 28/02/2017 08:44 2 River Cruise Atlas Brochure 2018.indd 2 28/02/2017 08:44 explore in Viking comfort In Norway they call it koselig. In Denmark, hygge. At Viking we simply call it comfort. And we believe it’s the only way to explore the world. Comfort is knowing that you are completely cared for in every way. It’s a glass of wine under a starlit sky. Good food in the company of good friends. Sinking in to a delicious king-sized bed and surrendering to the deepest of sleeps. It’s a feeling of contentment and wellbeing. Comfort is togetherness, a generosity of spirit and a very real sense of belonging. We hope that you enjoy browsing this brochure and find all the inspiration you need to explore the world in comfort with Viking during 2018. Call us on 0800 810 8220 3 River Cruise Atlas Brochure 2018.indd 3 28/02/2017 08:44 why Viking The world is an amazing place and we believe you deserve to see, hear, taste and touch it all. As an independently owned company, we are able to do things differently, to create journeys where you can immerse yourself in each destination, and explore its culture, history and cuisine. Our decades of experience give us an unrivalled level of expertise. And, with the largest, most innovative fleet of ships in the world, we are consistently voted best river cruise line by all the major players, including the British Travel Awards, Cruise International Awards and Times Travel Awards. -

Report on the Current Position of Poverty and Deprivation in Dumfries and Galloway 2020

Dumfries and Galloway Council Report on the current position of Poverty and Deprivation in Dumfries and Galloway 2020 3 December 2020 1 Contents 1. Introduction 1 2. National Context 2 3. Analysis by the Geographies 5 3.1 Dumfries and Galloway – Geography and Population 5 3.2 Geographies Used for Analysis of Poverty and Deprivation Data 6 4. Overview of Poverty in Dumfries and Galloway 10 4.1 Comparisons with the Crichton Institute Report and Trends over Time 13 5. Poverty at the Local Level 16 5.1 Digital Connectivity 17 5.2 Education and Skills 23 5.3 Employment 29 5.4 Fuel Poverty 44 5.5 Food Poverty 50 5.6 Health and Wellbeing 54 5.7 Housing 57 5.8 Income 67 5.9 Travel and Access to Services 75 5.10 Financial Inclusion 82 5.11 Child Poverty 85 6. Poverty and Protected Characteristics 88 6.1 Age 88 6.2 Disability 91 6.3 Gender Reassignment 93 6.4 Marriage and Civil Partnership 93 6.5 Pregnancy and Maternity 93 6.6 Race 93 6.7 Religion or Belief 101 6.8 Sex 101 6.9 Sexual Orientation 104 6.10 Veterans 105 7. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Poverty in Scotland 107 8. Summary and Conclusions 110 8.1 Overview of Poverty in Dumfries and Galloway 110 8.2 Digital Connectivity 110 8.3 Education and Skills 111 8.4 Employment 111 8.5 Fuel Poverty 112 8.6 Food Poverty 112 8.7 Health and Wellbeing 113 8.8 Housing 113 8.9 Income 113 8.10 Travel and Access to Services 114 8.11 Financial Inclusion 114 8.12 Child Poverty 114 8.13 Change Since 2016 115 8.14 Poverty and Protected Characteristics 116 Appendix 1 – Datazones 117 2 1. -

Wildlife Review Cover Image: Hedgehog by Keith Kirk

Dumfries & Galloway Wildlife Review Cover Image: Hedgehog by Keith Kirk. Keith is a former Dumfries & Galloway Council ranger and now helps to run Nocturnal Wildlife Tours based in Castle Douglas. The tours use a specially prepared night tours vehicle, complete with external mounted thermal camera and internal viewing screens. Each participant also has their own state- of-the-art thermal imaging device to use for the duration of the tour. This allows participants to detect animals as small as rabbits at up to 300 metres away or get close enough to see Badgers and Roe Deer going about their nightly routine without them knowing you’re there. For further information visit www.wildlifetours.co.uk email [email protected] or telephone 07483 131791 Contributing photographers p2 Small White butterfly © Ian Findlay, p4 Colvend coast ©Mark Pollitt, p5 Bittersweet © northeastwildlife.co.uk, Wildflower grassland ©Mark Pollitt, p6 Oblong Woodsia planting © National Trust for Scotland, Oblong Woodsia © Chris Miles, p8 Birdwatching © castigatio/Shutterstock, p9 Hedgehog in grass © northeastwildlife.co.uk, Hedgehog in leaves © Mark Bridger/Shutterstock, Hedgehog dropping © northeastwildlife.co.uk, p10 Cetacean watch at Mull of Galloway © DGERC, p11 Common Carder Bee © Bob Fitzsimmons, p12 Black Grouse confrontation © Sergey Uryadnikov/Shutterstock, p13 Black Grouse male ©Sergey Uryadnikov/Shutterstock, Female Black Grouse in flight © northeastwildlife.co.uk, Common Pipistrelle bat © Steven Farhall/ Shutterstock, p14 White Ermine © Mark Pollitt, -

Inshanks & Slockmill Farms

Inshanks & Slockmill Farms DRUMMORE • STRANRAER Inshanks & Slockmill Farms DRUMMORE • STRANRAER • WIGTOWNSHIRE • DG9 9HQ Drummore 3 miles, Stranraer 19 miles, Ayr 68 miles (all distances approximate) Highly Productive Coastal Dairy Farms on the Rhins Peninsula Inshanks Farmhouse (3 reception rooms, 4 bedrooms) Slockmill Farmhouse (2 reception rooms, 3 bedrooms) Three further residential dwellings Two farm steadings with predominantly modern buildings 24 point Milka-Ware rotary parlour and associated dairy buildings 433 acres ploughable pasture About 635 acres (257 hectares) in total For sale as a whole or in 2 lots Savills Dumfries Savills Edinburgh 28 Castle Street 8 Wemyss Place Dumfries Edinburgh DG1 1DG EH3 6DH 01387 263 066 0131 247 3720 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Situation Description Inshanks and Slockmill farms are situated in the Rhins of Portpatrick itself is a bustling village port, immensely popular Inshanks and Slockmill farms have been in the current Galloway peninsula, the most southerly part of Scotland with locals and tourists alike having a range of hotels, owners’ family since 1904, when the family took up a which is renowned for having a mild climate and one of the restaurants, golf course and tourist attractions. Highlights of tenancy from Logan Estate. The family went on to purchase earliest growing seasons in the country. This part of south the calendar include the annual Lifeboat week in summer and both Slockmill and Inshanks in 1947. The farms are run west Scotland is a genuinely rural area, well known for dairy the Folk Festival in September. together as a mixed dairy and beef enterprise, presently and livestock farming, magnificent countryside and dramatic carrying approximately 200 Ayrshire milking cows (and Further outdoor pursuits including mountain biking are coastline. -

Fhs Pubs List

Dumfries & Galloway FHS Publications List – 11 July 2013 Local History publications Memorial Inscriptions Price Wt Castledykes Park Dumfries £3.50 63g Mochrum £4.00 117g Annan Old Parish Church £3.50 100g Moffat £3.00 78g Covenanting Sites in the Stewartry: Stewartry Museum £1.50 50g Annan Old Burial Ground £3.50 130g Mouswald £2.50 65g Dalbeattie Parish Church (Opened 1843) £4.00 126g Applegarth and Sibbaldbie £2.00 60g Penpont £4.00 130g Family Record (recording family tree), A4: Aberdeen & NESFHS £3.80 140g Caerlaverock (Carlaverock) £3.00 85g Penninghame (N Stewart) £3.00 90g From Auchencairn to Glenkens&Portpatrick;Journal of D. Gibson 1814 -1843 : Macleod £4.50 300g Cairnryan £3.00 60g *Portpatrick New Cemetery £3.00 80g Canonbie £3.00 92g Portpatrick Old Cemetery £2.50 80g From Durisdeer & Castleton to Strachur: A Farm Diary 1847 - 52: Macleod & Maxwell £4.50 300g *Carsphairn £2.00 67g Ruthwell £3.00 95g Gaun Up To The Big Schule: Isabelle Gow [Lockerbie Academy] £10.00 450g Clachan of Penninghame £2.00 70g Sanquhar £4.00 115g Glenkens Schools over the Centuries: Anna Campbell £7.00 300g Closeburn £2.50 80g Sorbie £3.50 95g Heritage of the Solway J.Hawkins : Friends of Annandale & Eskdale Museums £12.00 300g Corsock MIs & Hearse Book £2.00 57g Stoneykirk and Kirkmadrine £2.50 180g History of Sorbie Parish Church: Donna Brewster £3.00 70g Cummertrees & Trailtrow £2.00 64g Stranraer Vol. 1 £2.50 130g Dalgarnock £2.00 70g Stranraer Vol. 2 £2.50 130g In the Tracks of Mortality - Robert Paterson, 1716-1801, Stonemason £3.50 90g Dalton £2.00 55g Stranraer Vol. -

Glenlochar Farmhouse Glenlochar, Castle Douglas

GLENLOCHAR FARMHOUSE GLENLOCHAR, CASTLE DOUGLAS GLENLOCHAR FARMHOUSE, GLENLOCHAR, CASTLE DOUGLAS A traditional farmhouse with outbuildings beautifully situated on the banks of the River Dee. Castle Douglas 3 miles ■ Dumfries 20 miles ■ Carlisle 54 miles Acreage – 1.75 acres (0.7 hectares) ■ 1 reception rooms. 3 bedrooms ■ Family home with potential for further development ■ Stunning riverside location ■ Range of outbuildings ■ Paddock ■ Fishing rights on River Dee along embankment boundary Castle Douglas 01556 505346 [email protected] SITUATION The nearby market town of Castle Douglas has a good range of shops, supermarkets, and other services, and is designated Dumfries & Galloways Food Town. The regional capital of Dumfries, about 20 miles distant, offers a wider range of shops, retail outlets and services including the Dumfries and Galloway Royal Infirmary, cinema, and the Crichton Campus providing further education courses, and railway station. The Southwest of Scotland is well known for its mild climate, attractive unspoilt countryside and abundance and diversity of its recreational and sporting pursuits, such as shooting, stalking, as well as trout and salmon fishing on the region’s numerous rivers and lochs. A wide variety of beaches, coastal paths and beautiful walks are within easy reach of the property. There are water sports and sailing on nearby Loch Ken as well as on the Solway, along with excellent hill walking in the nearby Galloway Hills and cycling along some of the numerous cycle routes, as well as a nationally renowned network of mountain biking routes in the hills and forest parks making up the Seven Stanes centres. The Galloway Forest Park well known for its beauty and tranquillity is also recognised as Britain’s first Dark Sky Park, and provides astronomers phenomenal views of the stars with a newly opened Observatory. -

3 St Andrews Street, Castle Douglas, DG7

FOR SALE DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY 3 ST ANDREW ST Castle Douglas DG7 1DE Offers over £75000 viewing by appointment only Viewing and contact information Property Estates & Programmes Andrew Maxwell 01387 273832 Dumfries and Galloway Council [email protected] Cargen Tower Nik Lane 01387 273833 Garroch Business Park [email protected] Garroch Loaning Dumfries DG2 8PN www.dumgal.gov.uk/property Location Offers Castle Douglas is a vibrant market Offers over £75,000 are invited. town at the centre of the Stewartry It is likely that a closing date for offers of Kirkcudbright. It is around 86 miles will be set. Prospective purchasers are south of Glasgow , 52 miles West of advised to note their interest in the Carlisle and 54 miles east of Stranraer. property with Property & Architectural Dumfries, the regional centre of Services, preferably through their Dumfries and Galloway lies 14 miles solicitor, in order that they may be East. The population of Castle Douglas advised of such. On the closing date is around 4,000 offers must be submitted in writing in a 3 St Andrew St is just off the town sealed envelope clearly marked: centre in a prominent position next to “Offer for 3 St Andrew StCastle Douglas the Town Hall, on the main road to Ayr. DG7 1DE”. All offers should be sent to: Legal Description Services The property is a 2 -storey plus F.A.O. Supervisory Solicitor attic floor building, constructed in Conveyancing whinstone and brick under a double pitched slated roof. Council Headquarters The ground and first floor contain a English Street mixture of offices, with toilets and Dumfries DG1 2DD kitchen located on the first floor. -

History of the Lands and Their Owners in Galloway

H.E NTIL , 4 Pfiffifinfi:-fit,mnuuugm‘é’r§ms, ».IVI\ ‘!{5_&mM;PAmnsox, _ V‘ V itbmnvncn. if,‘4ff V, f fixmmum ‘xnmonasfimwini cAa'1'm-no17t§1[.As'. xmgompnxenm. ,7’°':",*"-‘V"'{";‘.' ‘9“"3iLfA31Dan1r,_§v , qyuwgm." “,‘,« . ERRATA. Page 1, seventeenth line. For “jzim—g1'é.r,”read "j2'1r11—gr:ir." 16. Skaar, “had sasiik of the lands of Barskeoch, Skar,” has been twice erroneously printed. 19. Clouden, etc., page 4. For “ land of,” read “lands of.” 24. ,, For “ Lochenket," read “ Lochenkit.” 29.,9 For “ bo,” read “ b6." 48, seventh line. For “fill gici de gord1‘u1,”read“fill Riei de gordfin.” ,, nineteenth line. For “ Sr,” read “ Sr." 51 I ) 9 5’ For “fosse,” read “ fossé.” 63, sixteenth line. For “ your Lords,” read “ your Lord’s.” 143, first line. For “ godly,” etc., read “ Godly,” etc. 147, third line. For “ George Granville, Leveson Gower," read without the comma.after Granville. 150, ninth line. For “ Manor,” read “ Mona.” 155,fourth line at foot. For “ John Crak,” read “John Crai ." 157, twenty—seventhline. For “Ar-byll,” read “ Ar by1led.” 164, first line. For “ Galloway,” read “ Galtway.” ,, second line. For “ Galtway," read “ Galloway." 165, tenth line. For “ King Alpine," read “ King Alpin." ,, seventeenth line. For “ fosse,” read “ fossé.” 178, eleventh line. For “ Berwick,” read “ Berwickshire.” 200, tenth line. For “ Murmor,” read “ murinor.” 222, fifth line from foot. For “Alfred-Peter,” etc., read “Alfred Peter." 223 .Ba.rclosh Tower. The engraver has introduced two figures Of his own imagination, and not in our sketch. 230, fifth line from foot. For “ his douchter, four,” read “ his douchter four.” 248, tenth line.