Sur Les Chemins D'onagre

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2006-Journal 13Th Issue

Journal of Indian History and Culture JOURNAL OF INDIAN HISTORY AND CULTURE September 2006 Thirteenth Issue C.P. RAMASWAMI AIYAR INSTITUTE OF INDOLOGICAL RESEARCH The C.P. Ramaswami Aiyar Foundation 1 Eldams Road, Chennai 600 018, INDIA September 2006, Thirteenth Issue 1 Journal of Indian History and Culture Editor : Dr.G.J. Sudhakar Board of Editors Dr. K.V.Raman Dr. R.Nagaswami Dr.T.K.Venkatasubramaniam Dr. Nanditha Krishna Referees Dr. T.K. Venkatasubramaniam Prof. Vijaya Ramaswamy Dr. A. Satyanarayana Published by C.P.Ramaswami Aiyar Institute of Indological Research The C.P. Ramaswami Aiyar Foundation 1 Eldams Road Chennai 600 018 Tel : 2434 1778 / 2435 9366 Fax : 91-44-24351022 E-Mail: [email protected] Website: www.cprfoundation.org Subscription Rs.95/- (for 2 issues) Rs.180/-(for 4 issues) 2 September 2006, Thirteenth Issue Journal of Indian History and Culture CONTENTS ANCIENT HISTORY Bhima Deula : The Earliest Structure on the Summit of Mahendragiri - Some Reflections 9 Dr. R.C. Misro & B.Subudhi The Contribution of South India to Sanskrit Studies in Asia - A Case Study of Atula’s Mushikavamsa Mahakavya 16 T.P. Sankaran Kutty Nair The Horse and the Indus Saravati Civilization 33 Michel Danino Gender Aspects in Pallankuli in Tamilnadu 60 Dr. V. Balambal Ancient Indian and Pre-Columbian Native American Peception of the Earth ( Mythology, Iconography and Ritual Aspects) 80 Jayalakshmi Yegnaswamy MEDIEVAL HISTORY Antiquity of Documents in Karnataka and their Preservation Procedures 91 Dr. K.G. Vasantha Madhava Trade and Urbanisation in the Palar Valley during the Chola Period - A.D.900 - 1300 A.D. -

Hoysala King Ballala Iii (1291-1342 A.D)

FINAL REPORT UGC MINOR RESEARCH PROJECT on LIFE AND ACHIEVEMENTS: HOYSALA KING BALLALA III (1291-1342 A.D) Submitted by DR.N.SAVITHRI Associate Professor Department of History Mallamma Marimallappa Women’s Arts and Commerce College, Mysore-24 Submitted to UNIVERSITY GRANTS COMMISSION South Western Regional Office P.K.Block, Gandhinagar, Bangalore-560009 2017 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT First of all, I would like to Express My Gratitude and Indebtedness to University Grants Commission, New Delhi for awarding Minor Research Project in History. My Sincere thanks are due to Sri.Paramashivaiah.S, President of Marimallappa Educational Institutions. I am Grateful to Prof.Panchaksharaswamy.K.N, Honorary Secretary of Marimallappa Educational Institutions. I owe special thanks to Principal Sri.Dhananjaya.Y.D., Vice Principal Prapulla Chandra Kumar.S., Dr.Saraswathi.N., Sri Purushothama.K, Teaching and Non-Teaching Staff, members of Mallamma Marimallappa Women’s College, Mysore. I also thank K.B.Communications, Mysore has taken a lot of strain in computerszing my project work. I am Thankful to the Authorizes of the libraries in Karnataka for giving me permission to consult the necessary documents and books, pertaining to my project work. I thank all the temple guides and curators of minor Hoysala temples like Belur, Halebidu. Somanathapura, Thalkad, Melkote, Hosaholalu, kikkeri, Govindahalli, Nuggehalli, ext…. Several individuals and institution have helped me during the course of this study by generously sharing documents and other reference materials. I am thankful to all of them. Dr.N.Savithri Place: Date: 2 CERTIFICATE I Dr.N. Savithri Certify that the project entitled “LIFE AND ACHIEVEMENTS: HOYSALA KING BALLALA iii (1299-1342 A.D)” sponsored by University Grants Commission New Delhi under Minor Research Project is successfully completed by me. -

JETIR Research Journal

© 2018 JETIR December 2018, Volume 5, Issue 12 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) Learning from the Past: Study on Sustainable Features from Vernacular Architecture in Coastal Karnataka. 1Vikas.S.P, 2Sagar.V.G, 3Manoj Kumar.G, 4Neeraja Jayan 1Student, 6th sem, School of Architecture, REVA UNIVERSITY, 2Student, 6th sem, School of Architecture, REVA UNIVERSITY, 3Student, 6th sem, School of Architecture, REVA UNIVERSITY, 4Associate Professor, School of Architecture, REVA UNIVERSITY. Abstract: Vernacular architecture can be defined as that architecture characterized based on the function, construction materials and traditional knowledge specific and unique to its location. It is indigenous to a specific time and place and also incorporates the skills and expertise of local builders. The paper is elaborated on the basis of case studies of settlements in the Coastal region of Karnataka with special reference to Barkur and Brahmavar of Udupi regions. It has evolved over generations with the available building materials, climatic conditions and local craftsmanship. However, some examples of vernacular architecture are still found in Barkur and Brahmavar. These vernacular residential dwellings provided with various passive solar techniques including natural cooling systems and are more comfortable compared to the contemporary buildings in today's context. This research paper into various parameters which defines the vernacular architecture of coastal Karnataka and how these parameters can be interpreted in today’s context so that it can be used effectively in the future residential designs. keywords - sustainable, vernacular architecture, modern building, sustainability. I. INTRODUCTION Udupi is a city in the southwest Indian state of Karnataka and is known for its Hindu temples, including the 13th century Krishna temple which houses the statue of lord Krishna. -

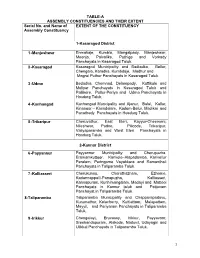

List of Lacs with Local Body Segments (PDF

TABLE-A ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCIES AND THEIR EXTENT Serial No. and Name of EXTENT OF THE CONSTITUENCY Assembly Constituency 1-Kasaragod District 1 -Manjeshwar Enmakaje, Kumbla, Mangalpady, Manjeshwar, Meenja, Paivalike, Puthige and Vorkady Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk. 2 -Kasaragod Kasaragod Municipality and Badiadka, Bellur, Chengala, Karadka, Kumbdaje, Madhur and Mogral Puthur Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk. 3 -Udma Bedadka, Chemnad, Delampady, Kuttikole and Muliyar Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk and Pallikere, Pullur-Periya and Udma Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 4 -Kanhangad Kanhangad Muncipality and Ajanur, Balal, Kallar, Kinanoor – Karindalam, Kodom-Belur, Madikai and Panathady Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 5 -Trikaripur Cheruvathur, East Eleri, Kayyur-Cheemeni, Nileshwar, Padne, Pilicode, Trikaripur, Valiyaparamba and West Eleri Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 2-Kannur District 6 -Payyannur Payyannur Municipality and Cherupuzha, Eramamkuttoor, Kankole–Alapadamba, Karivellur Peralam, Peringome Vayakkara and Ramanthali Panchayats in Taliparamba Taluk. 7 -Kalliasseri Cherukunnu, Cheruthazham, Ezhome, Kadannappalli-Panapuzha, Kalliasseri, Kannapuram, Kunhimangalam, Madayi and Mattool Panchayats in Kannur taluk and Pattuvam Panchayat in Taliparamba Taluk. 8-Taliparamba Taliparamba Municipality and Chapparapadavu, Kurumathur, Kolacherry, Kuttiattoor, Malapattam, Mayyil, and Pariyaram Panchayats in Taliparamba Taluk. 9 -Irikkur Chengalayi, Eruvassy, Irikkur, Payyavoor, Sreekandapuram, Alakode, Naduvil, Udayagiri and Ulikkal Panchayats in Taliparamba -

Department of Collegiate Education Dr. G. Shankar Govt Women's First

Department of Collegiate Education Dr. G. Shankar Govt Women’s First Grade College & Pg Study Centre Ajjarkadu, Udupi Personal Profile 2019-20 Part A - Basic Details of the Faculty Upload your 1. Name ` : Smt. Jayalakshmi recent passport 2. Designation : Assistant Professor in Economics size photo here 3. Department : Economics & Rural Development 4. Qualification : M.A. in Economics 5. NET/SLET : NET 6. Date of Joining : 07/09/2009 7. Date of joining present college : 07/09/2009 8. Teaching experience (in years) :16 Years 9. Phone/Cell No. : 9449211990 10. Email-Id : [email protected] 11. Residential Address : W/o Udaya naik Sri Laxmi Govinda Krupa Near Barkur Railway Station Maskibail Herady Village Barkur Udupi - 576 210 Part B – Criteria-wise Inputs/Information for the Year 2019-20 1.1.Details of classes engaged by the faculty during the year 2019-20 Sl Class Name of the Paper Hours per week Number of students No engaged in the class 1. I BCOM D Business Economics 04 81 Money and Public Finance 2. II BCOM E International Trade and 04 84 Finance I & II 3. I BA PRJ Rural Institutions in India 04 23 Rural Economy of India 4. II BA Monetary Economics 02 58 International Economics 5. I BBA Principles of Economics 02 27 Mangerial Economics 1.2.Details of membership of Academic Bodies during the year 2018-19. Sl Nature of the Academic Name of the institution Designation in the No Body academic body 1. BOE Mangalore University Member (2020) 1.3.1 Details of Certificate/ Diploma Courses/Others conducted as Coordinator during the academic year (if any) Sl Name of the Agency conducting the course Duration of the course No certificate/diploma (From-To) course/Others Nil 1.3.2 Details of Certificate/ Diploma Courses/Others attended during the academic year (if any) Sl Name of the certificate/diploma Agency that Duration of the course No course/Others conducted the course (From-To) 1. -

1. Introduction

1. INTRODUCTION 1.1. History Kasaragod, the northernmost district of Kerala, is endowed with rich natural resources and is noted for its majestic forts, ravishing rivers, hills, green valleys and beautiful beaches. The rich and varied cultural heritage of the district is portrayed through spectacular presentations of Theyyam, Yakshagana, Poorakkali, Kolkali and Mappilappattu. Seven languages are prevalent in Kasaragod. Malayalam is the administrative language. Other languages are Kannada, Tulu, Konkani, Marati, Urdu and Beary.Prior to State reorganization, Kasaragod was part of the South Kanara district.Kasaragod became a part of Malabar district following the reorganization of States and formation of unified Kerala State. Later, Kasaragod Taluk of Malabar district was bifurcated in to Kasaragod and Hosdurg Taluks and integrated with the then newly formed Cannanore district. Kasaragod became part of Kerala following the re-organization of states and formation of Kerala in 1st November 1956.The district was Kasaragod Taluk in Kannur District.The formation of Kasaragod district was a long felt ambition of the people.It is with the intention of bestowing maximum attention on the development of backward area, Kasaragod district was formed on 24th May,1984 as per GO (MS)No.520/84/RD, Dated 19.05.1984 by taking Kasaragod and Hosdurg taluks from the then Kannur district.The name Kasaragod is said to be derived from the word Kasaragod which means Nuxvemied Forest(Kanjirakuttam). 1.2. Physiography Kasaragod is bounded on the north and the east by Dakshina Kannada and Coorg districts of Karnataka State, on the south by Kannur district and on the west by the Lakshadweep Sea. -

District Census Handbook, Dakshina, Part XII-A, Series-11

CENSUS OF INDIA 1991 Series -11 KARNATAKA DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK DAKSHINA KANNADA DISTRICT PART XII - A VILLAGE AND TOWN DIRECTORY SOBHA NAMBISAN Director of Census Operations. Karnataka CONTENTS Page No. FOREWORD v-vi PREFACE vii-viii IMPORTANT STATISTICS xi-xiv ANALYTICAL NOTE xv-xliv Section,·I • Village Directory Explanatory Notc 1-9 Alphabetical List of Villages - Bantval C.O.Block 13-15 Village Directory Statement - Bantvill C.O.Block 16-33 Alphabetical List of Villages - Beltangadi C.O.Block 37-39 Village Directory Statement - Bcltangadi C.D.Block 40-63 Alphabetical List of Villages - Karkal C.D.Block 67-69 Village Directory Statement - Karkal C.D.Block 70-91 Alphabetical List of Villages - Kundapura C.O.Block 95-97 Village Directory Statement - Kundapur C.O.Block 98-119 Alphabetical List of Villages • Mangalore C.O.Block 123-124 Village Directory Statement - Mangalorc C.D.Block 126-137 Alphabetical List of Villages - PuHur C.D.Block 141-142 Village Directory Statement - Pullur C.D.Block 144-155 Alphabetical List of Villages - Sulya C.O.Block 159-160 Village Directory Statement - Sulya C.D.Block 162-171 Alphabetical List of Villages - Udupi C.D.Block 175-177 Village Directory Statement - Udupi C.D.Block 178-203 Appendix I!"IV • I Community Devclopment Blockwise Abstract for Educational, Medical and Other Amenities 206-209 II Land Utilisation Data in respect of Non-Municipal Census Towns 208-209 III List of Villages where no amenities except Drinking Water arc available 210 IV-A List of Villages according to the proportion of Scheduled Castes to Total Population by Ranges 211-216 IV-B List of Villages according to the proportion of Scheduled Tribes to Total Population by Ranges 217-222 (iii) Section-II - Town Din'ctory Explanatory Note 225-21:; Statement . -

Download Download

CONTENTS Guest Editor’s Note Arshad Islām 983 Articles Al-Waqf ’Ala Al-’Awlād A Case of Colonial Intervention in India I.A. Zilli 989 Transregional Comparison of the Waqf and Similar Donations in Human History Miura Toru 1007 Role of Women in the Creation and Management of Awqāf: A Historical Perspective Abdul Azim Islahi 1025 Turkish Waqf After the 2004 Aceh Tsunami Alaeddin Tekin and Arshad Islam 1047 Maqasid Sharia and Waqf: their Effect on Waqf Law and Economy. Mohammad Tahir Sabit 1065 Brief on Waqf, its Substitution (Al-Istibdāl) and Maqāṣid al-Sharī’ah Mohammed Farid Ali al-Fijawi , Maulana Akbar Shah @ U Tun Aung, and Alizaman D. Gamon 1093 Exploring the Dynamism of the Waqf Institution in Islam: A Critical Analysis of Cash Waqf Implementation in Malaysia Amilah Awang Abd Rahman and Abdul Bari Awang 1109 Historical Development of Waqf Governance in Bangladesh Thowhidul Islam 1129 The Chronicle of Waqf and Inception of Mosques in Malabar: A Study Based on the Qiṣṣat Manuscript Abbas Pannakal 1167 The Role of Waqf Properties in the Development of the Islamic Institutions in the Philippines: Issues and Challenges Ali Zaman 1191 The Foundations of Waqf Institutions: A Historical Perspective Irfan Ahmed Shaikh 1213 A Comparative Study of Governance of Waqf Institutions in India and Malaysia Anwar Aziz and Jawwad Ali 1229 The Significant Contribution of Caliphs in the Efflorescence of Muslim Librarianship: A Historical Account Rahmah Bt Ahmad H. Osman and Mawloud Mohadi 1247 INTELLECTUAL DISCOURSE, Special Issue (2018) 1167–1189 Copyright © IIUM Press ISSN 0128-4878 (Print); ISSN 2289-5639 (Online) The Chronicle of Waqf and Inception of Mosques in Malabar: A Study Based on Qissat Manuscript Abbas Panakkal* Abstract: The first mosque of South and South East Asia was established in Malabar and it was built with generous Waqf property. -

Handbooks Kerala

district handbooks of kerala CANNANORE DIREtTORATE OF , roBLICRElATIONS DISTRICT HANDBOOKS OF KERALA CANNANORE DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC RELATIONS Sli). NaticBttl Systems VuiU Naiiori-I Institute of Educational Planning and A ministration 1 7 -B.StiAV V 'ndo CONTENTS Page 1. Short history of Cannanore 1 2. Topography and Climate 2 3. Religions 3 4 . Customs and Manners 6 5. Kalari 7 6. Industries 8 7. Animal Husbandry 9 8. Special Agricultural Development Unit 9 9. Fisheries 10 10. Communication and Transport 11 11. Education 11 12. Medical Facilities 11 13. Forests 12 14 , Professional and Technical Institutions 13 15. Religious Institutions 14 16 . Places of Interest 16 17 . District at a glance 21 18 . Blocks and Panchayats 22 PART I Cannanore is the anglicised form oF the Malayalam word “ Karinur” . According to one view “ Kannur” is the variation of Kanathur, an ancient village, the name of which survive even today in ont! of the wards of Canna nore MunicipaUty. Perhaps, like several other ancient towns of Kerala, Cannanore also is named after one of the deities of the Hindu Pantheon. Thus “ Kannur” is the compound of the two words ‘Kannan’ meaning Lord Kris;hna, and TJr’ meaning place, the place of Lord Krishna, Short history of Cannanore Cannanore, the northernmost district of Kerala State, is constituted of territories which formed part of the erst while district ol' Malabar and South Ganara, prior to the rc-organisation of the States in 1956. Cannanore district was formed on January 1, 1957 by trifurcating the erstwhile Malabar district of the former Madras State. The district has a distinct history of its own which is in many rcspects independent of the history of other regions oi the State. -

Ahtl-European STRUGGLE by the MAPPILAS of MALABAR 1498-1921 AD

AHTl-EUROPEAn STRUGGLE BY THE MAPPILAS OF MALABAR 1498-1921 AD THESIS SUBMITTED FDR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE DF Sactnr of pitilnsopliQ IN HISTORY BY Supervisor Co-supervisor PROF. TARIQ AHMAD DR. KUNHALI V. Centre of Advanced Study Professor Department of History Department of History Aligarh Muslim University University of Calicut Al.garh (INDIA) Kerala (INDIA) T6479 VEVICATEV TO MY FAMILY CONTENTS SUPERVISORS' CERTIFICATE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT LIST OF MAPS LIST OF APPENDICES ABBREVIATIONS Page No. INTRODUCTION 1-9 CHAPTER I ADVENT OF ISLAM IN KERALA 10-37 CHAPTER II ARAB TRADE BEFORE THE COMING OF THE PORTUGUESE 38-59 CHAPTER III ARRIVAL OF THE PORTUGUESE AND ITS IMPACT ON THE SOCIETY 60-103 CHAPTER IV THE STRUGGLE OF THE MAPPILAS AGAINST THE BRITISH RULE IN 19™ CENTURY 104-177 CHAPTER V THE KHILAFAT MOVEMENT 178-222 CONCLUSION 223-228 GLOSSARY 229-231 MAPS 232-238 BIBLIOGRAPHY 239-265 APPENDICES 266-304 CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH - 202 002, INDIA CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the thesis "And - European Struggle by the Mappilas of Malabar 1498-1921 A.D." submitted for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the Aligarh Muslim University, is a record of bonafide research carried out by Salahudheen O.P. under our supervision. No part of the thesis has been submitted for award of any degree before. Supervisor Co-Supervisor Prof. Tariq Ahmad Dr. Kunhali.V. Centre of Advanced Study Prof. Department of History Department of History University of Calicut A.M.U. Aligarh Kerala ACKNOWLEDGEMENT My earnest gratitude is due to many scholars teachers and friends for assisting me in this work. -

Page Front 1-12.Pmd

REPORT ON THE DEVELOPMENT OF KASARAGOD DISTRICT Dr. P. Prabakaran October, 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS No. Topic Page No. Preface ........................................................................................................................................................ 5 PART-I LAW AND ORDER *(Already submitted in July 2012) ............................................ 9 PART - II DEVELOPMENT PERSPECTIVE 1. Background ....................................................................................................................................... 13 Development Sectors 2. Agriculture ................................................................................................................................................. 47 3. Animal Husbandry and Dairy Development.................................................................................. 113 4. Fisheries and Harbour Engineering................................................................................................... 133 5. Industries, Enterprises and Skill Development...............................................................................179 6. Tourism .................................................................................................................................................. 225 Physical Infrastructure 7. Power .................................................................................................................................................. 243 8. Improvement of Roads and Bridges in the district and development -

Act East: Asean-India Shared Cultural Heritage

ACT EAST: ASEAN-INDIA SHARED CULTURAL HERITAGE Culture is the key to the India-ASEAN partnership. Shared histori- cal ties, culture and knowledge continue to underpin India’s sustained interactions with Southeast Asia. The commonalities between India and Southeast Asia provide a platform for building synergies with the countries of the region. As India’s engagement with the ASEAN moves forward with support of the Act East Policy (AEP), the socio-cultural linkages between the two regions can be utilized effectively to expand collaboration, beyond economic and political domains into areas of education, tourism ACT EAST: and people to people contact. This book presents historical and contemporary dimensions between India and Southeast Asia with particular reference to cultural heritage. One of the recommenda- ASEAN-INDIA tions of this book is to continue our efforts to preserve, protect, and restore cultural heritage that represents the civilisational bonds SHARED CULTURAL between ASEAN and India. The book will serve as a knowledge product for policymakers, academics, private sector experts and HERITAGE regional cooperation practitioners; and is a must-read for anyone interested in the cultural heritage. fodkl'khy ns'kksa dh vuqla/ku ,oa lwpuk iz.kkyh Core IV-B, Fourth Floor, India Habitat Centre ACT EAST: ASEAN-INDIA SHARED CULTURAL HERITAGE ASEAN-INDIA SHARED CULTURAL ACT EAST: Lodhi Road, New Delhi-110 003, India Tel.: +91-11-2468 2177-80, Fax: +91-11-2468 2173-74 AIC E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] AIC fodkl'khy ns'kksa dh vuqla/ku