2006-Journal 13Th Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Study of Small Schools in Karnataka. Final Report.Pdf

Study of Small Schools in Karnataka – Final Draft Report Study of SMALL SCHOOLS IN KARNATAKA FFiinnaall RReeppoorrtt Submitted to: O/o State Project Director, Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan, Karnataka 15th September 2010 Catalyst Management Services Pvt. Ltd. #19, 1st Main, 1st Cross, Ashwathnagar RMV 2nd Stage, Bangalore – 560 094, India SSA Mission, Karnataka CMS, Bangalore Ph.: +91 (080) 23419616 Fax: +91 (080) 23417714 Email: raghu@cms -india.org: [email protected]; Website: http://www.catalysts.org Study of Small Schools in Karnataka – Final Draft Report Acknowledgement We thank Smt. Sandhya Venugopal Sharma,IAS, State Project Director, SSA Karnataka, Mr.Kulkarni, Director (Programmes), Mr.Hanumantharayappa - Joint Director (Quality), Mr. Bailanjaneya, Programme Officer, Prof. A. S Seetharamu, Consultant and all the staff of SSA at the head quarters for their whole hearted support extended for successfully completing the study on time. We also acknowledge Mr. R. G Nadadur, IAS, Secretary (Primary& Secondary Education), Mr.Shashidhar, IAS, Commissioner of Public Instruction and Mr. Sanjeev Kumar, IAS, Secretary (Planning) for their support and encouragement provided during the presentation on the final report. We thank all the field level functionaries specifically the BEOs, BRCs and the CRCs who despite their busy schedule could able to support the field staff in getting information from the schools. We are grateful to all the teachers of the small schools visited without whose cooperation we could not have completed this study on time. We thank the SDMC members and parents who despite their daily activities were able to spend time with our field team and provide useful feedback about their schools. -

District Census Handbook, Kolar, Part XII-B, Series-11

CENSUS OF INDIA 1991 Series -11 KARNATAKA DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK KOLAR DISTRICT PART XII- B VILLAGE AND TOWN WISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT SOBHA NAMBISAN Director of Census Operatio.ns, Karnataka CONTENTS 4J>agc No. FOREWORD v-vi PREFACE vii-viii IMPORTANT STATISTICS xi-xiv ANALYTICAL NOTE xv-xlv EXPLANATC>RY NOTES J--l A. Oi5'.lriCl Primary Census Ahstract (i) Villagcffown Primary Census Abstract Alphahetical List of Villages - Bagep"lJi CO.Block 27-32 Primary Census Abstract - Bagcpalli C.O.Block ~-l-() 1 Alph'lbetical List of Villages - Rangarapcl. CD.Block (15-73 Primmy Census Abs\ fact - Bal1g~If<IPd C.D.Bh)ck 7-l-\:!1 Alph:'lbctical List of Villages - Chik Ballapur C.D.Blnck 125-131) Primary Census Abstract - Cnik Balhlpur C.D.Block 132- 1('3 Alphabetical List of Villages - Chinwmani C.D.Block 167·17(1 Primary Census Abstract - Chintamani C.D.BllH:k 17X-225 Alphubctical List of Villages - Gauribidanur CD.Block Primary Census Abstract - Gauribidanur CO.Block Alphahetical List of Villages - Gudihanda C.D.Block Primary Ccnsus Ahstract - Ciudibanda CD.Blod, 271l-2X5 Alphahcl ;eal Li ... 1 of Villages - Kolar C.O.l3/nd; Primury Census Abslract Kolar C.O.Blud; Alph.,bclical List of Villages - Malur C.D.Block J.f5-353 Primary Census Abstract - Malur C.O.Block 354-397 Alphabetical List of Villages - 1\·1 1I Ibagal CO.Block 401-40X Primary Census Abstract - Mulbagill CD.Blud ... J 0-4... ll) Alphabetical List of Villages - Sidlaghall:l CD.Block Primary Census Abstract - Sidlaghatta C.D.Block ... U~I)-4t)5 Alphabetical List of Villages • Srinivaspur CO.Block ·N'I-507 Primary Census Abstract - SrinivasplIr CD.Block 50X-591 (i i i) (ii) Town Primary Ccn~u~ Ab~tract (\V~lId\\i<.,c) Alphabetical List of Towns 555 Bagepalli (MP) -, Bangarapet (TMC) Chik Ballapur (TMC) 550-559 Chintamani (TMC) 556-559 Gauribidanur (TMC) Gudibanda (MP) Kolar (CMC) Malur (TMC) Manchenahalli (M P) Mulbagal (TMC) Sidlaghatta (TMC) Sriniva~pur (MP) Kolar Gold Filed:; UA Sh-l-S71 B. -

Act East: Asean-India Shared Cultural Heritage

ACT EAST: ASEAN-INDIA SHARED CULTURAL HERITAGE Culture is the key to the India-ASEAN partnership. Shared histori- cal ties, culture and knowledge continue to underpin India’s sustained interactions with Southeast Asia. The commonalities between India and Southeast Asia provide a platform for building synergies with the countries of the region. As India’s engagement with the ASEAN moves forward with support of the Act East Policy (AEP), the socio-cultural linkages between the two regions can be utilized effectively to expand collaboration, beyond economic and political domains into areas of education, tourism ACT EAST: and people to people contact. This book presents historical and contemporary dimensions between India and Southeast Asia with particular reference to cultural heritage. One of the recommenda- ASEAN-INDIA tions of this book is to continue our efforts to preserve, protect, and restore cultural heritage that represents the civilisational bonds SHARED CULTURAL between ASEAN and India. The book will serve as a knowledge product for policymakers, academics, private sector experts and HERITAGE regional cooperation practitioners; and is a must-read for anyone interested in the cultural heritage. fodkl'khy ns'kksa dh vuqla/ku ,oa lwpuk iz.kkyh Core IV-B, Fourth Floor, India Habitat Centre ACT EAST: ASEAN-INDIA SHARED CULTURAL HERITAGE ASEAN-INDIA SHARED CULTURAL ACT EAST: Lodhi Road, New Delhi-110 003, India Tel.: +91-11-2468 2177-80, Fax: +91-11-2468 2173-74 AIC E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] AIC fodkl'khy ns'kksa dh vuqla/ku -

Invention of Perini Tradition; Dr. Nataraja Rama Krishna

Vol-3 Issue-3 2017 IJARIIE-ISSN(O)-2395-4396 Invention of Perini Tradition; Dr. Nataraja Rama Krishna Author : Vakkala Rama Krishna Designation : PhD Dance Scholar Department : Dance School : SN School of Arts and Communications University : University of Hyderabad Contact : +91 9704866232 / 9989917967 Email : [email protected] Brief note on Author : Mr. V. Ramakrishna is a freelance Kuchipudi performer, teacher and choreographer with 15 years of great experience in the field of Dance. Besides, he had acquired his master‟s degree in dance from the Department of Dance, Central University of Hyderabad and came out with distinction and prestigious University Gold Medal “Nataraja Ramakrishna‟s Sarada Devi medal”. Later he appointed as Asst. Professor at IIIT, and left the job for attaining PhD in dance from the Central University. He qualified in UGC NET and presently pursuing his PhD in „Origin and Evolution of Perini dance form‟ under the guidance of Prof. M.S.Siva Raju, Department of Dance, University of Hyderabad. Abstract: Dr. Nataraja Ramakrishna was a great scholar in digging the disappeared art forms like Perini, and naming Āndhra Nāṭyam to the Temple dance traditions (Ālaya Nṛtyālu). If Nataraja Ramakrishna would not be there, then Perini would be in History for study purpose but not vision to us. His most of the life dedicated to the dance by developing Ālaya Nṛtyas and propagation of Perini dance form. To propagate dance he made many lecture demonstrations, seminars and also had published over thirty books in Telugu and English languages on dance. Most of the books have become education for the dance students. -

Chikkaballapur District Disaster Management Plan 2019 - 20

Government of Karnataka Chikkaballapur District Disaster Management Plan 2019 - 20 District Disaster Management Authority (DDMA) Chikkaballapur Government of Karnataka Chikkaballapur District Disaster Management Plan 2019 - 20 Prepared by District Disaster Management Authority (DDMA) Chikkaballapur Smt. R Latha I.A.S Office of Deputy Commissioner Chairman of Disaster Management Chikkaballapur District, Chikkaballapur & Deputy Commissioner Phone: 08156-277001 Chikkaballapur District E-mail: [email protected] Preface The District Disaster Management Plan is a key part of an emergency management. It will play a significant role to address the unexpected disasters that occur in the district effectively. The information available in DDMP is valuable in terms of its use during disaster. Based on the history of various disasters that occur in the district, the plan has been so designed. This plan has been prepared based on the guidelines provided by the National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA). The District Disaster Management Plan developed involves some significant issues like Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability, Incident Response System (IRS) and the response mechanism in disaster management. The plan is mainly focused on drought mitigation and ground water conservation measures. We have started rejuvenation of Rivers, Kalyanis, Kere Kunte, open wells (Bavi) and also have constructed Multi-Arc Check Dams to improve Surface/Ground water. There are many projects in the pipeline project for Water Supply such as Yethinahole drinking water project, KC & HN Valley pipeline project to fill tanks and recharge ground water. Reserving the land for Hasiru Karnataka (Plantation), Green Fund for the plantation purpose, Rain water harvesting for Public/Private building are made compulsory to address drinking water crisis. -

Sur Les Chemins D'onagre

Sur les chemins d’Onagre Histoire et archéologie orientales Hommage à Monik Kervran édité par Claire Hardy-Guilbert, Hélène Renel, Axelle Rougeulle et Eric Vallet Avec les contributions de Vincent Bernard, Michel Boivin, Eloïse Brac de la Perrière, Dejanirah Couto, Julien Cuny, Ryka Gyselen, Claire Hardy-Guilbert, Elizabeth Lambourn, Fabien Lesguer, Pierre Lombard, Michel Mouton, Alastair Northedge, Valeria Piacentini Fiorani, Stéphane Pradines, Hélène Renel, Axelle Rougeulle, Jean-François Salles, Pierre Siméon, Vanessa Van Renterghem, Donald Whitcomb, Farzaneh Zareie Archaeopress Archaeology © Archaeopress and the authors, 2019. Archaeopress Publishing Ltd Summertown Pavilion 18-24 Middle Way Summertown Oxford OX2 7LG www.archaeopress.com ISBN 978-1-78491-984-9 ISBN 978-1-78491-985-6 (e-Pdf) © Archaeopress and the authors 2018 Cover illustration : Le château de Suse depuis le chantier de la Ville des Artisans, 1976 (© A. Rougeulle) All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electro- nic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owners. Printed in England by Oxuniprint, Oxford This book is available direct from Archaeopress or from our website www.archaeopress.com © Archaeopress and the authors, 2019. Sommaire Editeurs et contributeurs �����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������iii Avant – Propos ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ -

Kolar District

KOLAR DISTRICT CHAPTER I GENERAL OLAR, which is the headquarters town of the district and by Origin o'f K which name the district is also called, was known as D,ame ' Kolahala ', ' Kuvalala ' and 'Kolala' in the former times. There are varying accounts as to how the t:.wn got its name and three _of them are narrated below. According to a legend, Arjuna, son of Kritavirya, also called Kartaviryarjuna to distinguish him from Arjuna of Mahabharata fame, was ruling over a kingdom which included the Kolar a:.rea. This king had a boon conferred on him by sage Dl'.hltatraya, which gave him a thous~md arms and other mighty powers with which he oppressed both human beings and Devatas. Kartaviryarjuna is said to have humbled even Ravana, the mighty king of Lanka, by seizing and tying him up. About this time lived sage Jamadagni (nephew of Vishwamitra), who had married Renuka, daughter of the king Prasenajit. The couple had five sons, the last of whom was Parashurama or Rama with the axe. Sage Jamadagni had in his care Surabhi, the celestial cow of plenty given to him by Indra, which had the miraculous power to ,give all tltat was asked for. Karttwiryarjuna in one of his hunting expeditions chanced to visit the ashrama of Jamadagni and the sage regaled him in such a magnificent manner that his curiosity was roused and he was not satisfied till he learnt the secret about the heavenly animal and its powers. Avarice took l10ld of king Kartavir~ yarjuna and he demanded the cow for himsel:t. -

A Comparison of Concert Patterns in Carnatic and Hindustani Music Sakuntala Narasimhan — 134

THE JOURNAL OF THE MUSIC ACADEMY MADRAS: DEVOTED TO m ADVANCEMENT OF THE SCIENCE AND ART OF MUSIC V ol. L IV 1983 R 3 P E I r j t nrcfri gsr fiigiPi n “ I dwell not in Vaiknntka, nor in tlie hearts of Togihs nor in the Sun: (but) where my bhaktas sing, there be I, Narada!" Edited by T. S. FARTHASARATHY 1983 The Music Academy Madras 306, T. T. K. Road, M adras -600 014 Annual Subscription - Inland - Rs. 15: Foreign $ 3.00 OURSELVES This Journal is published as an'Annual. • ; i '■■■ \V All correspondence relating to the Journal should be addressed and all books etc., intended for it should be sent to The Editor, Journal of the Music Academy, 306, Mowbray’s Road, Madras-600014. Articles on music and dance are accepted for publication on the understanding that they are contributed solely to the Journal of the Music Academy. Manuscripts should be legibly written or, preferably, type* written (double-spaced and on one side of the paper only) and should be signed by the writer (giving his or her address in full). The Editor of the Journal is not responsible for the views ex pressed by contributors in their articles. JOURNAL COMMITTEE OF THE MUSIC ACADEMY 1. Sri T. S. Parthasarathy — Editor (and Secretary, Music Academy) 2. „ T. V. Rajagopalan — Trustee 3. „ S. Ramaswamy — Executive Trustee 4. „ Sandhyavandanam Sreenivasa Rao — Member 5. „ S. Ramanathan — Member 6. „ NS. Natarajan Secretaries of the Music 7. „ R. Santhanam > Academy,-Ex-officio 8. ,, T. S. Rangarajan ' members. C ^ N T E N I S . -

L\1YSORE GAZETTEER MYSORE GAZETTEER

l\1YSORE GAZETTEER MYSORE GAZETTEER COMPILED FOR GOVERNMENT VOLUME II HISTORICAL PART l EDITED BY C. HAY AV ADANA RAO, B.A., B.L, Fellow, University of Mysore, Editor, Mysore Economic Journal, Bangalore. NEW EDITIO~ BANGALORE; PRINTED AT THE GOVERNMENT PRESS 1930 PREFACE HIS, Volume, forming Volume II of the ltfysore T Gazetteer, deals in a comprehensive manner with the History of Mysore. A two-fold plan has been adopted in the treatment of this subject. In view of the progress of archffiological research in the State during the past forty years, occasion has been taken to deal in an adequate fashion with the sources from which the materials for the recon struction of its ancient history are derived. The information scattered in the Journals of the learned Societies and Reports on Archreology has been carefully sifted and collected under appropriate heads. Among these are Epigraphy, Numismatics, Sculpture and Painting, Architecture, etc. The evidence available from these different sources has been brought together to show not merely their utility in elucidating the history of Mysore during its earliest times, for which written records are not available, but also to trace, as far as may be, with their aid, periods of history which would otherwi8e be wholly a blank. In dealing with that part of the history of Mysore for wbich written records are to any extent available, a more familiar plan has been adopted. It has been divided into periods and each period has been treated under convenient sub-heads. No person who writes on the history of Mysore can do so without being indebted to :Mr. -

Manu V. Devadevan a Prehistory of Hinduism

Manu V. Devadevan A Prehistory of Hinduism Manu V. Devadevan A Prehistory of Hinduism Managing Editor: Katarzyna Tempczyk Series Editor: Ishita Banerjee-Dube Language Editor: Wayne Smith Open Access Hinduism ISBN: 978-3-11-051736-1 e-ISBN: 978-3-11-051737-8 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/. © 2016 Manu V. Devadevan Published by De Gruyter Open Ltd, Warsaw/Berlin Part of Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston The book is published with open access at www.degruyter.com. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Managing Editor: Katarzyna Tempczyk Series Editor:Ishita Banerjee-Dube Language Editor: Wayne Smith www.degruyteropen.com Cover illustration: © Manu V. Devadevan In memory of U. R. Ananthamurthy Contents Acknowledgements VIII A Guide to Pronunciation of Diacritical Marks XI 1 Introduction 1 2 Indumauḷi’s Grief and the Making of Religious Identities 13 3 Forests of Learning and the Invention of Religious Traditions 43 4 Heredity, Genealogies, and the Advent of the New Monastery 80 5 Miracles, Ethicality, and the Great Divergence 112 6 Sainthood in Transition and the Crisis of Alienation 145 7 Epilogue 174 Bibliography 184 List of Tables 196 Index 197 Acknowledgements My parents, Kanakambika Antherjanam and Vishnu Namboodiri, were my first teachers. From them, I learnt to persevere, and to stay detached. This book would not have been possible without these fundamental lessons. -

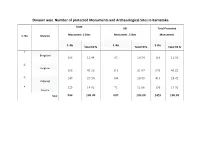

Division Wise Number of Protected Monuments and Archaeological Sites in Karnataka

Division wise Number of protected Monuments and Archaeological Sites in Karnataka State ASI Total Protected S. No Division Monument / Sites Monument / Sites Monuments S. No S. No S. No Total TO % Total TO % Total TO % 1 Bangalore 105 12.44 63 10.34 168 11.56 2 Belgaum 365 43.25 311 51.07 676 46.52 3 249 29.50 164 26.93 413 28.42 Kalgurugi 4 125 14.81 71 11.66 196 13.51 Mysore Total 844 100.00 609 100.00 1453 100.00 Division wise Number of protected Monuments and Archaeological Sites in Karnataka Bangalore Division Serial Per Total No. of Overall pre- Name of the District Number Total No. of cent Per protected protected ASI Total No. of Monument / Sites cent % Monument / protected Monument / Sites % Sites monuments 1 Bangalore City 7 2 9 2 Bangalore Rural 9 5 14 3 Chitradurga 8 6 14 4 Davangere 8 9 17 5 Kolara 15 6 21 6 Shimoga 12 26 38 7 Tumkur 29 6 35 8 Chikkaballapur 4 2 6 9 Ramanagara 13 1 14 Total 105 12.44 63 10.34 168 11.56 Division wise Number of protected Monuments and Archaeological Sites in Karnataka Belgaum Division Total No. of Overall pre- Serial Per Name of the District Total No. of Per protected protected Number cent ASI Total No. of Monument / Sites cent % Monument / protected % Monument / Sites Sites monuments 10 Bagalkot 22 110 132 11 Belgaum 58 38 96 12 Vijayapura 45 96 141 13 Dharwad 27 6 33 14 Gadag 44 14 58 15 Haveri 118 12 130 16 Uttara Kannada 51 35 86 Total 365 43.25 311 51.07 676 46.52 Division wise Number of protected Monuments and Archaeological Sites in Karnataka Kalburagi Division Serial Per Total protected -

Historical Engagements and Interreligious Encounters Jews and Christians in Premodern and Early Modern Asia and Africa

6 (2018) Editorial: 1-33 Historical Engagements and Interreligious Encounters Jews and Christians in Premodern and Early Modern Asia and Africa ALEXANDRA CUFFEL Center for Religious Studies, Ruhr-Universität Bochum, Germany OPHIRA GAMLIEL Theology and Religious Studies, University of Glasgow, Scotland License: This contribution to Entangled Religions is published under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 International). The license can be accessed at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/4.0/ or is available from Creative Commons, 559 Nathan Abbot Way, Stanford, California 94305, USA © 2018 Alexandra Cuffel, Ophira Gamliel Entangled Religions 6 (2018) http://dx.doi.org./10.13154/er.v6.2018.1–33 Entangled Histories and Interreligious Encounters Entangled Histories and Interreligious Encounters Jews and Christians in Premodern and Early Modern Asia and Africa ALEXANDRA CUFFEL, OPHIRA GAMLIEL Ruhr- Universität Bochum, Germany; University of Glasgow, Scotland Scholars examining pre-modern Jewish encounters with non-Jewish communities have increasingly emphasized the multiple and complex dimensions of these interactions within the same or connected cultural milieux. Ritual and legal practices, religious concepts, artistic motifs, and forms of material culture, economic and other quotidian exchanges, and of course polemical treatises, exegesis, and literary representations have all captured researchers’ attention (Baumgarten, Karras, and Medler 2017; Secunda 2013; Bonfil, Irshai, and Talgam 2012; Simonsohn 2011; Shalev- Eyni 2010; Gaudette 2010; Holo 2009; Kogman-Appel and Meyer 2008; Cuffel 2007; Becker and Reed 2007; Meri 2002). With regard to the pre-modern Islamic world, scholars have regularly noted the parallel experiences and status of Jews and Christians under Islamic rule, as well as shared cultural practices between Muslims and dhimmi communities (Russ-Fishbane 2015; Safran 2011; Mayeur-Jaouen 2005; Meri 1999; Fenton 1995, 1997, 2000; Cohen 1994).