Medieval Trade, Markets and Modes of Exchange

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dairying in Malabar: a Venture of the Landowning Based on Women's Work?

Ind. Jn. ofAgri. Econ. Vol.57, No.4, Oct-Dec. 2002 Dairying in Malabar: A Venture of the Landowning based on Women's Work? D. Narayana* INTRODUCTION India occupies the second place in the production of milk in the world. The strategy adopted to achieve such remarkable growth in milk production has been a replication of the `Anand pattern' of co-operative dairying in other parts of India using the proceeds of European Economic Commission (EEC) dairy surpluses donated to India under the Operation Flood (OF) programme. The Indian dairy co- operative strategy has, however, proved to be fiercely controversial. One of the major criticisms of the strategy has been that too much focus on transforming the production and marketing technology along western lines has led to a situation where the policy 'took care of the dairy animal but not the human beings who own the animal'. Some dairy unions have come forward to set up foundations and trusts to address the development problems of milk producers. The well-known ones are, The Thribhuvandas Foundation' at Anand, Visaka Medical, Educational and Welfare Trust, and Varana Co-operative Society. They mainly focus on health and educational needs of milk producers and employees. These pioneering efforts have inspired other milk unions. The Malabar Regional Co-operative Milk Producers' Union (MRCMPU)2 has recently registered a welfare trust named, Malabar Rural Development Foundation (MRDF). The mission objective of MRDF is to make a sustainable improvement in the quality of life of dairy farmers by undertaking specific interventions. The planning of interventions for the welfare of dairy farmers in the Malabar region by MRDF called for an understanding of them in the larger social context. -

2006-Journal 13Th Issue

Journal of Indian History and Culture JOURNAL OF INDIAN HISTORY AND CULTURE September 2006 Thirteenth Issue C.P. RAMASWAMI AIYAR INSTITUTE OF INDOLOGICAL RESEARCH The C.P. Ramaswami Aiyar Foundation 1 Eldams Road, Chennai 600 018, INDIA September 2006, Thirteenth Issue 1 Journal of Indian History and Culture Editor : Dr.G.J. Sudhakar Board of Editors Dr. K.V.Raman Dr. R.Nagaswami Dr.T.K.Venkatasubramaniam Dr. Nanditha Krishna Referees Dr. T.K. Venkatasubramaniam Prof. Vijaya Ramaswamy Dr. A. Satyanarayana Published by C.P.Ramaswami Aiyar Institute of Indological Research The C.P. Ramaswami Aiyar Foundation 1 Eldams Road Chennai 600 018 Tel : 2434 1778 / 2435 9366 Fax : 91-44-24351022 E-Mail: [email protected] Website: www.cprfoundation.org Subscription Rs.95/- (for 2 issues) Rs.180/-(for 4 issues) 2 September 2006, Thirteenth Issue Journal of Indian History and Culture CONTENTS ANCIENT HISTORY Bhima Deula : The Earliest Structure on the Summit of Mahendragiri - Some Reflections 9 Dr. R.C. Misro & B.Subudhi The Contribution of South India to Sanskrit Studies in Asia - A Case Study of Atula’s Mushikavamsa Mahakavya 16 T.P. Sankaran Kutty Nair The Horse and the Indus Saravati Civilization 33 Michel Danino Gender Aspects in Pallankuli in Tamilnadu 60 Dr. V. Balambal Ancient Indian and Pre-Columbian Native American Peception of the Earth ( Mythology, Iconography and Ritual Aspects) 80 Jayalakshmi Yegnaswamy MEDIEVAL HISTORY Antiquity of Documents in Karnataka and their Preservation Procedures 91 Dr. K.G. Vasantha Madhava Trade and Urbanisation in the Palar Valley during the Chola Period - A.D.900 - 1300 A.D. -

KERALA SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT PROJECT (KSWMP) with Financial Assistance from the World Bank

KERALA SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT Public Disclosure Authorized PROJECT (KSWMP) INTRODUCTION AND STRATEGIC ENVIROMENTAL ASSESSMENT OF WASTE Public Disclosure Authorized MANAGEMENT SECTOR IN KERALA VOLUME I JUNE 2020 Public Disclosure Authorized Prepared by SUCHITWA MISSION Public Disclosure Authorized GOVERNMENT OF KERALA Contents 1 This is the STRATEGIC ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT OF WASTE MANAGEMENT SECTOR IN KERALA AND ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL MANAGEMENT FRAMEWORK for the KERALA SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT PROJECT (KSWMP) with financial assistance from the World Bank. This is hereby disclosed for comments/suggestions of the public/stakeholders. Send your comments/suggestions to SUCHITWA MISSION, Swaraj Bhavan, Base Floor (-1), Nanthancodu, Kowdiar, Thiruvananthapuram-695003, Kerala, India or email: [email protected] Contents 2 Table of Contents CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION TO THE PROJECT .................................................. 1 1.1 Program Description ................................................................................. 1 1.1.1 Proposed Project Components ..................................................................... 1 1.1.2 Environmental Characteristics of the Project Location............................... 2 1.2 Need for an Environmental Management Framework ........................... 3 1.3 Overview of the Environmental Assessment and Framework ............. 3 1.3.1 Purpose of the SEA and ESMF ...................................................................... 3 1.3.2 The ESMF process ........................................................................................ -

Payment Locations - Muthoot

Payment Locations - Muthoot District Region Br.Code Branch Name Branch Address Branch Town Name Postel Code Branch Contact Number Royale Arcade Building, Kochalummoodu, ALLEPPEY KOZHENCHERY 4365 Kochalummoodu Mavelikkara 690570 +91-479-2358277 Kallimel P.O, Mavelikkara, Alappuzha District S. Devi building, kizhakkenada, puliyoor p.o, ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 4180 PULIYOOR chenganur, alappuzha dist, pin – 689510, CHENGANUR 689510 0479-2464433 kerala Kizhakkethalekal Building, Opp.Malankkara CHENGANNUR - ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 3777 Catholic Church, Mc Road,Chengannur, CHENGANNUR - HOSPITAL ROAD 689121 0479-2457077 HOSPITAL ROAD Alleppey Dist, Pin Code - 689121 Muthoot Finance Ltd, Akeril Puthenparambil ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 2672 MELPADAM MELPADAM 689627 479-2318545 Building ;Melpadam;Pincode- 689627 Kochumadam Building,Near Ksrtc Bus Stand, ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 2219 MAVELIKARA KSRTC MAVELIKARA KSRTC 689101 0469-2342656 Mavelikara-6890101 Thattarethu Buldg,Karakkad P.O,Chengannur, ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 1837 KARAKKAD KARAKKAD 689504 0479-2422687 Pin-689504 Kalluvilayil Bulg, Ennakkad P.O Alleppy,Pin- ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 1481 ENNAKKAD ENNAKKAD 689624 0479-2466886 689624 Himagiri Complex,Kallumala,Thekke Junction, ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 1228 KALLUMALA KALLUMALA 690101 0479-2344449 Mavelikkara-690101 CHERUKOLE Anugraha Complex, Near Subhananda ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 846 CHERUKOLE MAVELIKARA 690104 04793295897 MAVELIKARA Ashramam, Cherukole,Mavelikara, 690104 Oondamparampil O V Chacko Memorial ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 668 THIRUVANVANDOOR THIRUVANVANDOOR 689109 0479-2429349 -

PONNANI PEPPER PROJECT History Ponnani Is Popularly Known As “The Mecca of Kerala”

PONNANI PEPPER PROJECT HISTORY Ponnani is popularly known as “the Mecca of Kerala”. As an ancient harbour city, it was a major trading hub in the Malabar region, the northernmost end of the state. There are many tales that try to explain how the place got its name. According to one, the prominent Brahmin family of Azhvancherry Thambrakkal once held sway over the land. During their heydays, they offered ponnu aana [elephants made of gold] to the temples, and this gave the land the name “Ponnani”. According to another, due to trade, ponnu [gold] from the Arab lands reached India for the first time at this place, and thus caused it to be named “Ponnani”. It is believed that a place that is referred to as “Tyndis” in the Greek book titled Periplus of the Erythraean Sea is Ponnani. However historians have not been able to establish the exact location of Tyndis beyond doubt. Nor has any archaeological evidence been recovered to confirm this belief. Politically too, Ponnani had great importance in the past. The Zamorins (rulers of Calicut) considered Ponnani as their second headquarters. When Tipu Sultan invaded Kerala in 1766, Ponnani was annexed to the Mysore kingdom. Later when the British colonized the land, Ponnani came under the Bombay Province for a brief interval of time. Still later, it was annexed Malabar and was considered part of the Madras Province for one-and-a-half centuries. Until 1861, Ponnani was the headquarters of Koottanad taluk, and with the formation of the state of Kerala in 1956, it became a taluk in Palakkad district. -

Scheduled Caste Sub Plan (Scsp) 2014-15

Government of Kerala SCHEDULED CASTE SUB PLAN (SCSP) 2014-15 M iiF P A DC D14980 Directorate of Scheduled Caste Development Department Thiruvananthapuram April 2014 Planng^ , noD- documentation CONTENTS Page No; 1 Preface 3 2 Introduction 4 3 Budget Estimates 2014-15 5 4 Schemes of Scheduled Caste Development Department 10 5 Schemes implementing through Public Works Department 17 6 Schemes implementing through Local Bodies 18 . 7 Schemes implementing through Rural Development 19 Department 8 Special Central Assistance to Scheduled C ^te Sub Plan 20 9 100% Centrally Sponsored Schemes 21 10 50% Centrally Sponsored Schemes 24 11 Budget Speech 2014-15 26 12 Governor’s Address 2014-15 27 13 SCP Allocation to Local Bodies - District-wise 28 14 Thiruvananthapuram 29 15 Kollam 31 16 Pathanamthitta 33 17 Alappuzha 35 18 Kottayam 37 19 Idukki 39 20 Emakulam 41 21 Thrissur 44 22 Palakkad 47 23 Malappuram 50 24 Kozhikode 53 25 Wayanad 55 24 Kaimur 56 25 Kasaragod 58 26 Scheduled Caste Development Directorate 60 27 District SC development Offices 61 PREFACE The Planning Commission had approved the State Plan of Kerala for an outlay of Rs. 20,000.00 Crore for the year 2014-15. From the total State Plan, an outlay of Rs 1962.00 Crore has been earmarked for Scheduled Caste Sub Plan (SCSP), which is in proportion to the percentage of Scheduled Castes to the total population of the State. As we all know, the Scheduled Caste Sub Plan (SCSP) is aimed at (a) Economic development through beneficiary oriented programs for raising their income and creating assets; (b) Schemes for infrastructure development through provision of drinking water supply, link roads, house-sites, housing etc. -

The Political Economy of Agrarian Policies in Kerala: a Study of State Intervention in Agricultural Commodity Markets with Particular Reference to Dairy Markets

THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF AGRARIAN POLICIES IN KERALA: A STUDY OF STATE INTERVENTION IN AGRICULTURAL COMMODITY MARKETS WITH PARTICULAR REFERENCE TO DAIRY MARKETS VELAYUDHAN RAJAGOPALAN Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Ph D Department Of Government London School O f Economics & Political Science University O f London April 1993 UMI Number: U062852 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Disscrrlation Publishing UMI U062852 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 P ”7 <ü i o ABSTRACT This thesis analyzes the nature of State intervention in agricultural commodity markets in the Indian province of Kerala in the period 1960-80. Attributing the lack of dynamism in the agrarian sector to market imperfections, the Government of Kerala has intervened both directly through departmentally run institutions and indirectly through public sector corporations. The failure of both these institutional devices encouraged the government to adopt marketing co-operatives as the preferred instruments of market intervention. Co-operatives with their decentralised, democratic structures are^ in theory, capable of combining autonomous decision-making capacity with accountability to farmer members. -

Robert D. Kaplan: Monsoon Study Guide

Scholars Crossing Faculty Publications and Presentations Helms School of Government 2016 Robert D. Kaplan: Monsoon Study Guide Steven Alan Samson Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/gov_fac_pubs Part of the Other Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons, Political Science Commons, and the Public Affairs, Public Policy and Public Administration Commons Recommended Citation Samson, Steven Alan, "Robert D. Kaplan: Monsoon Study Guide" (2016). Faculty Publications and Presentations. 445. https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/gov_fac_pubs/445 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Helms School of Government at Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 ROBERT D. KAPLAN: MONSOON STUDY GUIDE, 2016 Steven Alan Samson PREFACE: THE RIMLAND OF EURASIA Outline A. OVERVIEW (xi-xiv) 1. The Map of Eurasia Defined the 20C 2. Greater Indian Ocean a. Rimland of Eurasia [Nicholas Spykman’s term for the strategically sensitive Eurasian coastal regions, including the Indian Ocean/West Pacific Ocean littoral] b. Asian Century 3. Importance of Seas and Coastlines a. Littorals b. C. R. Boxer: Monsoon Asia 4. Vasco da Gama 5. India 6. Gradual Power Shift a. Arabian Sea 1) Pakistan b. Bay of Bengal 1) Burma 7. Charles Verlinden 8. Indian Ocean Region as an Idea 9. Topics a. Strategic overview of the region b. Oman 1) Portugal 2) Perennial relationship between the sea and the desert c. Massive Chinese harbor projects d. Islamic radicalization e. -

![The Legend Marthanda Varma [1] C.Parthiban Sarathi [1] II M.A History, Scott Christian College(Autonomous), Nagercoil](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8445/the-legend-marthanda-varma-1-c-parthiban-sarathi-1-ii-m-a-history-scott-christian-college-autonomous-nagercoil-488445.webp)

The Legend Marthanda Varma [1] C.Parthiban Sarathi [1] II M.A History, Scott Christian College(Autonomous), Nagercoil

ISSN (Online) 2456 -1304 International Journal of Science, Engineering and Management (IJSEM) Vol 2, Issue 12, December 2017 The legend Marthanda Varma [1] C.Parthiban Sarathi [1] II M.A History, Scott Christian College(Autonomous), Nagercoil. Abstract:-- Marthanda Varma the founder of modern Travancore. He was born in 1705. Anizham Tirunal Marthanda Varma rule of Travancore in 1929. Marthanda Varma headquarters in Kalkulam. Marthanda Varma very important policy in Blood and Iron policy. Marthanda Varma reorganised the financial department the palace of Padmanabhapuram was improved and several new buildings. There was improvement of communication following the opening of new Roads and canals. Irrigation works like the ponmana and puthen dams. Marthanda Varma rulling period very important war in Battle of Colachel. The As the Dutch military team captain Eustachius De Lannoy and our soldiers surrendered in Travancore king. Marthanda Varma asked Dutch captain Delannoy to work for the Travancore army Delannoy accepted to take service under the maharaja Delannoy trained with European style of military drill and tactics. Commander in chief of the Travancore military, locally called as valia kapitaan. This king period Padmanabhaswamy temple in Ottakkal mandapam built in Marthanda Varma. The king decided to donate his recalm to Sri Padmanabha and thereafter rule as the deity's vice regent the dedication took place on January 3, 1750 and thereafter he was referred to as Padmanabhadasa Thrippadidanam. The legend king Marthanda Varma 7 July 1758 is dead. Keywords:-- Marthanda Varma, Battle of Colachel, Dutch military captain Delannoy INTRODUCTION English and the Dutch and would have completely quelled the rebels but for the timidity and weakness of his uncle the Anizham Tirunal Marthanda Varma was a ruler of the king who completed him to desist. -

Requiring Body SIA Unit

SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT STUDY FINAL REPORT LAND ACQUISITION FOR THE CONSTRUCTION OF OIL DEPOT &APPROACH ROAD FOR HPCL/BPCL AT PAYYANUR VILLAGE IN KANNUR DISTRICT 15th JANUARY 2019 Requiring Body SIA Unit RAJAGIRI outREACH HINDUSTAN PETROLEUM Rajagiri College of Social Sciences CORPORATION LTD. Rajagiri P.O, Kalamassery SOUTHZONE Pin: 683104 Phone no: 0484-2550785, 2911332 www.rajagiri.edu 1 CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1.1 Project and Public Purpose 1.2 Location 1.3 Size and Attributes of Land Acquisition 1.4 Alternatives Considered 1.5 Social Impacts 1.6. Mitigation Measures CHAPTER 2 DETAILED PROJECT DESCRIPTION 2.1. Background of the Project including Developers background 2.2. Rationale for the Project 2.3. Details of Project –Size, Location, Production Targets, Costs and Risks 2.4. Examination of Alternatives 2.5. Phases of the Project Construction 2.6.Core Design Features and Size and Type of Facilities 2.7. Need for Ancillary Infrastructural Facilities 2.8.Work force requirements 2.9. Details of Studies Conducted Earlier 2.10 Applicable Legislations and Policies CHAPTER 3 TEAM COMPOSITION, STUDY APPROACH AND METHODOLOGY 3.1 Details of the Study Team 3.2 Methodology and Tools Used 3.3 Sampling Methodology Used 3.4. Schedule of Consultations with Key Stakeholders 3.5. Limitation of the Study CHAPTER 4 LAND ASSESSMENT 4.1 Entire area of impact under the influence of the project 4.2 Total Land Requirement for the Project 4.3 Present use of any Public Utilized land in the Vicinity of the Project Area 2 4.4 Land Already Purchased, Alienated, Leased and Intended use for Each Plot of Land 4.5. -

Trends in Indian Historiography

HIS2B02 - TRENDS IN INDIAN HISTORIOGRAPHY SEMESTER II Core Course BA HISTORY CBCSSUG (2019) (2019 Admissions Onwards) School of Distance Education University of Calicut HIS2 B02 Trends in Indian Hstoriography University of Calicut School of Distance Education Study Material B.A.HISTORY II SEMESTER CBCSSUG (2019 Admissions Onwards) HIS2B02 TRENDS IN INDIAN HISTORIOGRAPHY Prepared by: Module I & II :Dr. Ancy. M. A Assistant Professor School of Distance Education University of Calicut. Module III & IV : Vivek. A. B Assistant Professor School of Distance Education University of Calicut. Scrutinized by : Dr.V V Haridas, Associate Professor, Dept. of History, University of Calicut. MODULE I Historical Consciousness in Pre-British India Jain and Bhuddhist tradition Condition of Hindu Society before Buddha Buddhism is centered upon the life and teachings of Gautama Buddha, where as Jainism is centered on the life and teachings of Mahavira. Both Buddhism and Jainism believe in the concept of karma as a binding force responsible for the suffering of beings upon earth. One of the common features of Bhuddhism and jainism is the organisation of monastic orders or communities of Monks. Buddhism is a polytheistic religion. Its main goal is to gain enlightenment. Jainism is also polytheistic religion and its goals are based on non-violence and liberation the soul. The Vedic idea of the divine power of speech was developed into the philosophical concept of hymn as the human expression of the etheric vibrations which permeate space and which were first knowable cause of creation itself. Jainism and Buddhism which were instrumental in bringing about lot of changes in the social life and culture of India. -

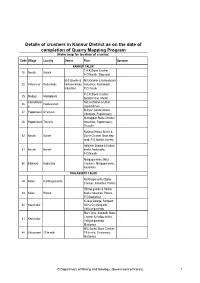

Details of Crushers in Kannur District As on the Date of Completion Of

Details of crushers in Kannur District as on the date of completion of Quarry Mapping Program (Refer map for location of crusher) Code Village Locality Owner Firm Operator KANNUR TALUK T.A.K.Stone Crusher , 16 Narath Narath P.O.Narath, Step road M/S Granite & M/S Granite & Hollowbricks 20 Valiyannur Kadankode Holloaw bricks, Industries, Kadankode , industries P.O.Varam P.C.K.Stone Crusher, 25 Madayi Madaippara Balakrishnan, Madai Cherukkunn Natural Stone Crusher, 26 Pookavanam u Jayakrishnan Muliyan Constructions, 27 Pappinisseri Chunkam Chunkam, Pappinissery Muthappan Stone Crusher 28 Pappinisseri Thuruthi Industries, Pappinissery, Thuruthi National Hollow Bricks & 52 Narath Narath Stone Crusher, Near step road, P.O.Narath, Kannur Abhilash Granite & Hollow 53 Narath Narath bricks, Neduvathu, P.O.Narath Maligaparambu Metal 60 Edakkad Kadachira Crushers, Maligaparambu, Kadachira THALASSERY TALUK Karithurparambu Stone 38 Kolari Karithurparambu Crusher, Industries, Porora Hill top granite & Hollow 39 Kolari Porora bricks industries, Porora, P.O.Mattannur K.Jose George, Sampath 40 Keezhallur Stone Crushing unit, Velliyamparambu Mary Jose, Sampath Stone Crusher & Hollow bricks, 41 Keezhallur Velliyamparambu, Mattannur M/S Santhi Stone Crusher, 44 Chavesseri 19 th mile 19 th mile, Chavassery, Mattannur © Department of Mining and Geology, Government of Kerala. 1 Code Village Locality Owner Firm Operator M/S Conical Hollow bricks 45 Chavesseri Parambil industries, Chavassery, Mattannur Jaya Metals, 46 Keezhur Uliyil Choothuvepumpara K.P.Sathar, Blue Diamond Vellayamparamb 47 Keezhallur Granite Industries, u Velliyamparambu M/S Classic Stone Crusher 48 Keezhallur Vellay & Hollow Bricks Industries, Vellayamparambu C.Laxmanan, Uthara Stone 49 Koodali Vellaparambu Crusher, Vellaparambu Fivestar Stone Crusher & Hollow Bricks, 50 Keezhur Keezhurkunnu Keezhurkunnu, Keezhur P.O.