A Comparison of Concert Patterns in Carnatic and Hindustani Music Sakuntala Narasimhan — 134

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Towards Automatic Audio Segmentation of Indian Carnatic Music

Friedrich-Alexander-Universit¨at Erlangen-Nurnberg¨ Master Thesis Towards Automatic Audio Segmentation of Indian Carnatic Music submitted by Venkatesh Kulkarni submitted July 29, 2014 Supervisor / Advisor Dr. Balaji Thoshkahna Prof. Dr. Meinard Muller¨ Reviewers Prof. Dr. Meinard Muller¨ International Audio Laboratories Erlangen A Joint Institution of the Friedrich-Alexander-Universit¨at Erlangen-N¨urnberg (FAU) and Fraunhofer Institute for Integrated Circuits IIS ERKLARUNG¨ Erkl¨arung Hiermit versichere ich an Eides statt, dass ich die vorliegende Arbeit selbstst¨andig und ohne Benutzung anderer als der angegebenen Hilfsmittel angefertigt habe. Die aus anderen Quellen oder indirekt ubernommenen¨ Daten und Konzepte sind unter Angabe der Quelle gekennzeichnet. Die Arbeit wurde bisher weder im In- noch im Ausland in gleicher oder ¨ahnlicher Form in einem Verfahren zur Erlangung eines akademischen Grades vorgelegt. Erlangen, July 29, 2014 Venkatesh Kulkarni i Master Thesis, Venkatesh Kulkarni ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Acknowledgements I would like to express my gratitude to my supervisor, Dr. Balaji Thoshkahna, whose expertise, understanding and patience added considerably to my learning experience. I appreciate his vast knowledge and skill in many areas (e.g., signal processing, Carnatic music, ethics and interaction with participants).He provided me with direction, technical support and became more of a friend, than a supervisor. A very special thanks goes out to my Prof. Dr. Meinard M¨uller,without whose motivation and encouragement, I would not have considered a graduate career in music signal analysis research. Prof. Dr. Meinard M¨ulleris the one professor/teacher who truly made a difference in my life. He was always there to give his valuable and inspiring ideas during my thesis which motivated me to think like a researcher. -

Syllabus for Post Graduate Programme in Music

1 Appendix to U.O.No.Acad/C1/13058/2020, dated 10.12.2020 KANNUR UNIVERSITY SYLLABUS FOR POST GRADUATE PROGRAMME IN MUSIC UNDER CHOICE BASED CREDIT SEMESTER SYSTEM FROM 2020 ADMISSION NAME OF THE DEPARTMENT: DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC NAME OF THE PROGRAMME: MA MUSIC DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC KANNUR UNIVERSITY SWAMI ANANDA THEERTHA CAMPUS EDAT PO, PAYYANUR PIN: 670327 2 SYLLABUS FOR POST GRADUATE PROGRAMME IN MUSIC UNDER CHOICE BASED CREDIT SEMESTER SYSTEM FROM 2020 ADMISSION NAME OF THE DEPARTMENT: DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC NAME OF THE PROGRAMME: M A (MUSIC) ABOUT THE DEPARTMENT. The Department of Music, Kannur University was established in 2002. Department offers MA Music programme and PhD. So far 17 batches of students have passed out from this Department. This Department is the only institution offering PG programme in Music in Malabar area of Kerala. The Department is functioning at Swami Ananda Theertha Campus, Kannur University, Edat, Payyanur. The Department has a well-equipped library with more than 1800 books and subscription to over 10 Journals on Music. We have gooddigital collection of recordings of well-known musicians. The Department also possesses variety of musical instruments such as Tambura, Veena, Violin, Mridangam, Key board, Harmonium etc. The Department is active in the research of various facets of music. So far 7 scholars have been awarded Ph D and two Ph D thesis are under evaluation. Department of Music conducts Seminars, Lecture programmes and Music concerts. Department of Music has conducted seminars and workshops in collaboration with Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts-New Delhi, All India Radio, Zonal Cultural Centre under the Ministry of Culture, Government of India, and Folklore Academy, Kannur. -

Fusion Without Confusion Raga Basics Indian

Fusion Without Confusion Raga Basics Indian Rhythm Basics Solkattu, also known as konnakol is the art of performing percussion syllables vocally. It comes from the Carnatic music tradition of South India and is mostly used in conjunction with instrumental music and dance instruction, although it has been widely adopted throughout the world as a modern composition and performance tool. Similarly, the music of North India has its own system of rhythm vocalization that is based on Bols, which are the vocalization of specific sounds that correspond to specific sounds that are made on the drums of North India, most notably the Tabla drums. Like in the south, the bols are used in musical training, as well as composition and performance. In addition, solkattu sounds are often referred to as bols, and the practice of reciting bols in the north is sometimes referred to as solkattu, so the distinction between the two practices is blurred a bit. The exercises and compositions we will discuss contain bols that are found in both North and South India, however they come from the tradition of the North Indian tabla drums. Furthermore, the theoretical aspect of the compositions is distinctly from the Hindustani, (north Indian) tradition. Hence, for the purpose of this presentation, the use of the term Solkattu refers to the broader, more general practice of Indian rhythmic language. South Indian Percussion Mridangam Dolak Kanjira Gattam North Indian Percussion Tabla Baya (a.k.a. Tabla) Pakhawaj Indian Rhythm Terms Tal (also tala, taal, or taala) – The Indian system of rhythm. Tal literally means "clap". -

Chapter 6 SOME NEWLY CREATED MISHRA RAGA

Chapter 6 SOME NEWLY CREATED MISHRA RAGA SOME NEW CREATIONS : Raga Jogkauns : (A landmark of modem mishra raga) This is an excellent creation of late Pt. Jagannath Buva Purohit "Gunidas". It is a combination of Raga Jog, Chandrakauns (both old and newly created by Prof. Devdhar). Chalan: tit Pi <4 - ST Pt Wf, FlI'PI’ll m n *r n n P( \ w n *t \st, v 3tj\stv X{ *f nji # \*tst^*ftPtsi^sft srPr tft *r *t, v i\5 *nt h *t, *rr Here, (1) Phrase *tT *1 *1*1 is used for raga Jog (2) Phrase *tT *1 *1 *IJHT is also used for raga Jog (3) Phrase tfT Pt «(P[ tn is used for raga Chandrakaus (4) Phrase 4 tfT is also used for raga Chandrakaus (5) Phrase *1 *t ^ ’s also used for raga Chandrakaus (6) Phrase 4 st Pi^st 4 is used for od Chandrakaus While discussing this raga with Prof. N.V.Patwardhan on 18/12/88 he told us that he had a wide discussion with Buva and Buva has told him that while creating the raga Jogkaus the old Chandrakaus having komal Nishad was in his mind. So he had used phrase 4 % 4... which now an identical phrase of raga Jogkaus ( *t tt 4t^t 4 4^44 ) Also discussing this raga with Pt. Arvind Parikh a sitar mastreo and disciple of Sh. Ustad VilayatKhan; he also told that he believes only one newly created mishra raga which may be called as a land mark of mishra raga is only raga Jogkaus created by Pt. -

M.A-Music-Vocal-Syllabus.Pdf

BANGALORE UNIVERSITY NAAC ACCREDITED WITH ‘A’ GRADE P.G. DEPARTMENT OF PERFORMING ARTS JNANABHARATHI, BANGALORE-560056 MUSIC SYLLABUS – M.A KARNATAKA MUSIC VOCAL AND INSTRUMENTAL (VEENA, VIOLIN AND FLUTE) CBCS SYSTEM- 2014 Dr. B.M. Jayashree. Professor of Music Chairperson, BOS (PG) M.A. KARNATAKA MUSIC VOCAL AND INSTRUMENTAL (VEENA, VIOLIN AND FLUTE) Semester scheme syllabus CBCS Scheme of Examination, continuous Evaluation and other Requirements: 1. ELIGIBILITY: A Degree with music vocal/instrumental as one of the optional subject with at least 50% in the concerned optional subject an merit internal among these applicant Of A Graduate with minimum of 50% marks secured in the senior grade examination in music (vocal/instrumental) conducted by secondary education board of Karnataka OR a graduate with a minimum of 50% marks secured in PG Diploma or 2 years diploma or 4 year certificate course in vocal/instrumental music conducted either by any recognized Universities of any state out side Karnataka or central institution/Universities Any degree with: a) Any certificate course in music b) All India Radio/Doordarshan gradation c) Any diploma in music or five years of learning certificate by any veteran musician d) Entrance test (practical) is compulsory for admission. 2. M.A. MUSIC course consists of four semesters. 3. First semester will have three theory paper (core), three practical papers (core) and one practical paper (soft core). 4. Second semester will have three theory papers (core), two practical papers (core), one is project work/Dissertation practical paper and one is practical paper (soft core) 5. Third semester will have two theory papers (core), three practical papers (core) and one is open Elective Practical paper 6. -

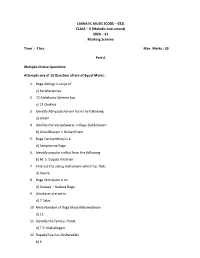

CARNATIC MUSIC (CODE – 032) CLASS – X (Melodic Instrument) 2020 – 21 Marking Scheme

CARNATIC MUSIC (CODE – 032) CLASS – X (Melodic Instrument) 2020 – 21 Marking Scheme Time - 2 hrs. Max. Marks : 30 Part A Multiple Choice Questions: Attempts any of 15 Question all are of Equal Marks : 1. Raga Abhogi is Janya of a) Karaharapriya 2. 72 Melakarta Scheme has c) 12 Chakras 3. Identify AbhyasaGhanam form the following d) Gitam 4. Idenfity the VarjyaSwaras in Raga SuddoSaveri b) GhanDharam – NishanDham 5. Raga Harikambhoji is a d) Sampoorna Raga 6. Identify popular vidilist from the following b) M. S. Gopala Krishnan 7. Find out the string instrument which has frets d) Veena 8. Raga Mohanam is an d) Audava – Audava Raga 9. Alankaras are set to d) 7 Talas 10 Mela Number of Raga Maya MalawaGoula d) 15 11. Identify the famous flutist d) T R. Mahalingam 12. RupakaTala has AksharaKals b) 6 13. Indentify composer of Navagrehakritis c) MuthuswaniDikshitan 14. Essential angas of kriti are a) Pallavi-Anuppallavi- Charanam b) Pallavi –multifplecharanma c) Pallavi – MukkyiSwaram d) Pallavi – Charanam 15. Raga SuddaDeven is Janya of a) Sankarabharanam 16. Composer of Famous GhanePanchartnaKritis – identify a) Thyagaraja 17. Find out most important accompanying instrument for a vocal concert b) Mridangam 18. A musical form set to different ragas c) Ragamalika 19. Identify dance from of music b) Tillana 20. Raga Sri Ranjani is Janya of a) Karahara Priya 21. Find out the popular Vena artist d) S. Bala Chander Part B Answer any five questions. All questions carry equal marks 5X3 = 15 1. Gitam : Gitam are the simplest musical form. The term “Gita” means song it is melodic extension of raga in which it is composed. -

1 ; Mahatma Gandhi University B. A. Music Programme(Vocal

1 ; MAHATMA GANDHI UNIVERSITY B. A. MUSIC PROGRAMME(VOCAL) COURSE DETAILS Sem Course Title Hrs/ Cred Exam Hrs. Total Week it Practical 30 mts Credit Theory 3 hrs. Common Course – 1 5 4 3 Common Course – 2 4 3 3 I Common Course – 3 4 4 3 20 Core Course – 1 (Practical) 7 4 30 mts 1st Complementary – 1 (Instrument) 3 3 Practical 30 mts 2nd Complementary – 1 (Theory) 2 2 3 Common Course – 4 5 4 3 Common Course – 5 4 3 3 II Common Course – 6 4 4 3 20 Core Course – 2 (Practical) 7 4 30 mts 1st Complementary – 2 (Instrument) 3 3 Practical 30 mts 2nd Complementary – 2 (Theory) 2 2 3 Common Course – 7 5 4 3 Common Course – 8 5 4 3 III Core Course – 3 (Theory) 3 4 3 19 Core Course – 4 (Practical) 7 3 30 mts 1st Complementary – 3 (Instrument) 3 2 Practical 30 mts 2nd Complementary – 3 (Theory) 2 2 3 Common Course – 9 5 4 3 Common Course – 10 5 4 3 IV Core Course – 5 (Theory) 3 4 3 19 Core Course – 6 (Practical) 7 3 30 mts 1st Complementary – 4 (Instrument) 3 2 Practical 30 mts 2nd Complementary – 4 (Theory) 2 2 3 Core Course – 7 (Theory) 4 4 3 Core Course – 8 (Practical) 6 4 30 mts V Core Course – 9 (Practical) 5 4 30 mts 21 Core Course – 10 (Practical) 5 4 30 mts Open Course – 1 (Practical/Theory) 3 4 Practical 30 mts Theory 3 hrs Course Work/ Project Work – 1 2 1 Core Course – 11 (Theory) 4 4 3 Core Course – 12 (Practical) 6 4 30 mts VI Core Course – 13 (Practical) 5 4 30 mts 21 Core Course – 14 (Practical) 5 4 30 mts Elective (Practical/Theory) 3 4 Practical 30 mts Theory 3 hrs Course Work/ Project Work – 2 2 1 Total 150 120 120 Core & Complementary 104 hrs 82 credits Common Course 46 hrs 38 credits Practical examination will be conducted at the end of each semester 2 MAHATMA GANDHI UNIVERSITY B. -

A History of Indian Music by the Same Author

68253 > OUP 880 5-8-74 10,000 . OSMANIA UNIVERSITY LIBRARY Call No.' poa U Accession No. Author'P OU H Title H; This bookok should bHeturned on or befoAbefoifc the marked * ^^k^t' below, nfro . ] A HISTORY OF INDIAN MUSIC BY THE SAME AUTHOR On Music : 1. Historical Development of Indian Music (Awarded the Rabindra Prize in 1960). 2. Bharatiya Sangiter Itihasa (Sanglta O Samskriti), Vols. I & II. (Awarded the Stisir Memorial Prize In 1958). 3. Raga O Rupa (Melody and Form), Vols. I & II. 4. Dhrupada-mala (with Notations). 5. Sangite Rabindranath. 6. Sangita-sarasamgraha by Ghanashyama Narahari (edited). 7. Historical Study of Indian Music ( ....in the press). On Philosophy : 1. Philosophy of Progress and Perfection. (A Comparative Study) 2. Philosophy of the World and the Absolute. 3. Abhedananda-darshana. 4. Tirtharenu. Other Books : 1. Mana O Manusha. 2. Sri Durga (An Iconographical Study). 3. Christ the Saviour. u PQ O o VM o Si < |o l "" c 13 o U 'ij 15 1 I "S S 4-> > >-J 3 'C (J o I A HISTORY OF INDIAN MUSIC' b SWAMI PRAJNANANANDA VOLUME ONE ( Ancient Period ) RAMAKRISHNA VEDANTA MATH CALCUTTA : INDIA. Published by Swaxni Adytaanda Ramakrishna Vedanta Math, Calcutta-6. First Published in May, 1963 All Rights Reserved by Ramakrishna Vedanta Math, Calcutta. Printed by Benoy Ratan Sinha at Bharati Printing Works, 141, Vivekananda Road, Calcutta-6. Plates printed by Messrs. Bengal Autotype Co. Private Ltd. Cornwallis Street, Calcutta. DEDICATED TO SWAMI VIVEKANANDA AND HIS SPIRITUAL BROTHER SWAMI ABHEDANANDA PREFACE Before attempting to write an elaborate history of Indian Music, I had a mind to write a concise one for the students. -

The Journal the Music Academy

ISSN. 0970-3101 THE JOURNAL OF THE MUSIC ACADEMY DEVOTED TO THE ADVANCEMENT OF THE SCIENCE AND ART OF MUSIC Vol. LX 1989 *ra im rfra era faw ifa s i r ? ii ''I dwell not,in Vaikuntha, nor in the hearts of Yogins nor in the Sun; (but) where my bhaktas sing, there be I, Narada!" Edited by: T. S. PARTHASARATHY The Music Academy Madras 306, T. T. K. Road, Madras-600014 Annual Subscription — Inland Rs. 20 : Foreign $ 3-00 OURSELVES This Journal is published as an Annual. All correspondence relating to the Journal should be addressed and all books etc., intended for it should be sent to The Editor, Journal of the Music Academy, 306, T. T. K. Road, Madras-600 014. Articles on music and dance are accepted for publication on the understanding that they are contributed solely to the Journal of the Music Academy. Manuscripts should be legibly written or, preferably, type written (double-spaced and on one side of the paper only) and should be signed by the writter (giving his or her address in full). The Editor of the Journal is not responsible for the views expressed by contributors in their articles. CONTENTS Pages The 62nd Madras Music Conference - Official Report 1-64 The Bhakta and External Worship (Sri Tyagaraja’s Utsava Sampradaya Songs) Dr. William J. Jackson 65-91 Rhythmic Analysis of Some Selected Tiruppugazh Songs Prof. Trichy Sankaran (Canada) 92-102 Saugita Lakshana Prachina Paddhati 7. S. Parthasarathy & P. K. Rajagopa/a Iyer 103-124 Indian Music on the March 7. S. -

A Study on the Effects of Music Listening Based on Indian Time Theory of Ragas on Patients with Pre-Hypertension

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research Volume 9, Issue 1, January-2018 ISSN 2229-5518 370 A STUDY ON THE EFFECTS OF MUSIC LISTENING BASED ON INDIAN TIME THEORY OF RAGAS ON PATIENTS WITH PRE-HYPERTENSION Suguna V Masters in Indian Music, PGD in Music Therapy IJSER IJSER © 2018 http://www.ijser.org International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research Volume 9, Issue 1, January-2018 ISSN 2229-5518 371 1. ABSTRACT 1.1 INTRODUCTION: Pre-hypertension is more prevalent than hypertension worldwide. Management of pre- hypertensive state is usually with lifestyle modifications including, listening to relaxing music that can help in preventing the progressive rise in blood pressure and cardio-vascular disorders. This study was taken up to find out the effects of listening to Indian classical music based on time theory of Ragas (playing a Raga at the right time) on pre-hypertensive patients and how they respond to this concept. 1.2 AIM & OBJECTIVES: It has been undertaken with an aim to understand the effect of listening to Indian classical instrumental music based on the time theory of Ragas on pre-hypertensive patients. 1.3 SUBJECTS & METHODS: This study is a repeated measure randomized group designed study with a music listening experimental group and a control group receiving no music intervention. The study was conductedIJSER at Center for Music Therapy Education and Research at Mahatma Gandhi medical college and research institute, Pondicherry. 30 Pre-hypertensive out patients from the Department of General Medicine participated in the study after giving informed consent form. Systolic BP (SBP), Diastolic BP (DBP), Pulse Rate (PR) and Respiratory Rate (RR) measures were taken on baseline and every week for a month. -

2008 President-Elect - S

52 SRUTI BOARD OF DIRECTORS SRUTI DAY President - C. Nataraj December 2008 President-elect - S. Vidyasankar Treasurer - Venkat Kilambi Director of Resources & Development - Ramaa Nathan Director of Publications & Outreach - Vijaya Viswanathan Director of Marketing & Publicity - Srinivas Pothukuchi Director 1 - Revathi Sivakumar Director 2 Seetha Ayyalasomayajula Resource Committee - Ramaa Nathan, Uma Prabhakar, C. Nataraj, Vidyashankar Sundaresan, and Venkat Kilambi Sruti web site managed by V V Raman S R U T I The India Music & Dance Society Philadelphia, PA 2 51 Editor’s Note Welcome to our year end event, Sruti Day. This is- sue of Sruti Ranjani carries articles by some of our young- Solution to Jumble sters, who have achieved certain significant milestones in their journeys as performing artists of classical music and dance. Apart from this, our adult members have contrib- uted interesting articles that you are certain to enjoy along C O P with some puzzles and a couple of reviews of past Sruti concerts. Again, many thanks to all for taking the time to V E R S E write for this issue. H A P P Y Thanks, O D O R D E M O N S Vijaya Viswanathan 610-640-5375 C O M P O S E R’S CONTENTS DAY 1. Program - 3 2. About the Artists 3 3. Articles by members of the community 4 4. Puzzles 48 50 3 PROGRAM 2:00 PM General Body Meeting and Elections to 2009- 2010 Board (open to Sruti members only) 3:30 PM Snack Break 4:00 PM Carnatic Flute Concert by Shri V. -

English 710-882

AN ETHNOMUSICOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVE ON KANIYAN KOOTHU Aaron J. Paige This paper will analyze some of the strategies by which Kaniyans, a minority com- munity from the Southern districts of Tamil Nadu, use music as a vehicle to negoti- ate, reconcile, and understand social, cultural, and economic change. Kaniyan Koothu performances are generally commissioned for kodai festivals, during which Kaniyans sing lengthy ballads. These stories vary locally from village to village and recount the adventures, exploits, and virtues of gods and goddesses specific to the area and community in which they are worshipped. While these narratives are en- tertaining in their own right, they also serve as springboards for subjective compari- son and interpretation. Kaniyans thus, transform mythological legends into modern social commentary. In a world perceived to be growing increasingly complicated by globalization and modernization, these folk musicians openly voice in performance both their concern for the loss of traditional values and their trepidation that Tamil culture, tamizh panpaadu – particularly village culture, gramiya panpaadu – are gradually being displaced by foreign principles, products, and technologies. In con- tradistinction to this conservative rhetoric, the Kaniyans, in recent years, have made major reformations to their own musical practice. Using specific textual examples, the first part of this paper will look at the ways in which musicians’ semi-improvised narratives foster solidarity under the rubric of a shared Tamil language and cultural identity. The second part of this paper, by way of musical examples, will attempt to illuminate how these same musicians are engaged in redefining and reformulating their musical tradition through the appropriation and integration of rhythmic models characteristic of Carnatic drumming.