Ashanti Alston in Interview with Hilary Darcy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The History of the Black Panther Party 1966-1972 : a Curriculum Tool for Afrikan American Studies

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-1990 The history of the Black Panther Party 1966-1972 : a curriculum tool for Afrikan American studies. Kit Kim Holder University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Holder, Kit Kim, "The history of the Black Panther Party 1966-1972 : a curriculum tool for Afrikan American studies." (1990). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 4663. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/4663 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE HISTORY OF THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY 1966-1972 A CURRICULUM TOOL FOR AFRIKAN AMERICAN STUDIES A Dissertation Presented By KIT KIM HOLDER Submitted to the Graduate School of the■ University of Massachusetts in partial fulfills of the requirements for the degree of doctor of education May 1990 School of Education Copyright by Kit Kim Holder, 1990 All Rights Reserved THE HISTORY OF THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY 1966 - 1972 A CURRICULUM TOOL FOR AFRIKAN AMERICAN STUDIES Dissertation Presented by KIT KIM HOLDER Approved as to Style and Content by ABSTRACT THE HISTORY OF THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY 1966-1971 A CURRICULUM TOOL FOR AFRIKAN AMERICAN STUDIES MAY 1990 KIT KIM HOLDER, B.A. HAMPSHIRE COLLEGE M.S. BANK STREET SCHOOL OF EDUCATION Ed.D., UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS Directed by: Professor Meyer Weinberg The Black Panther Party existed for a very short period of time, but within this period it became a central force in the Afrikan American human rights/civil rights movements. -

Black Anarchism, Pedro Riberio

TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction.....................................................................................................................2 2. The Principles of Anarchism, Lucy Parsons....................................................................3 3. Anarchism and the Black Revolution, Lorenzo Komboa’Ervin......................................10 4. Beyond Nationalism, But not Without it, Ashanti Alston...............................................72 5. Anarchy Can’t Fight Alone, Kuwasi Balagoon...............................................................76 6. Anarchism’s Future in Africa, Sam Mbah......................................................................80 7. Domingo Passos: The Brazilian Bakunin.......................................................................86 8. Where Do We Go From Here, Michael Kimble..............................................................89 9. Senzala or Quilombo: Reflections on APOC and the fate of Black Anarchism, Pedro Riberio...........................................................................................................................91 10. Interview: Afro-Colombian Anarchist David López Rodríguez, Lisa Manzanilla & Bran- don King........................................................................................................................96 11. 1996: Ballot or the Bullet: The Strengths and Weaknesses of the Electoral Process in the U.S. and its relation to Black political power today, Greg Jackson......................100 12. The Incomprehensible -

Working Against Racism from White Subject Positions: White Anti-Racism, New Abolitionism & Intersectional Anti-White Irish Diasporic Nationalism

Working Against Racism from White Subject Positions: White Anti-Racism, New Abolitionism & Intersectional Anti-White Irish Diasporic Nationalism By Matthew W. Horton A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Education and the Designated Emphasis in Critical Theory in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Dr. Na’ilah Nasir, Chair Dr. Daniel Perlstein Dr. Keith Feldman Summer 2019 Working Against Racism from White Subject Positions Matthew W. Horton 2019 ABSTRACT Working Against Racism from White Subject Positions: White Anti-Racism, New Abolitionism & Intersectional Anti-White Irish Diasporic Nationalism by Matthew W. Horton Doctor of Philosophy in Education and the Designated Emphasis in Critical Theory University of California, Berkeley Professor Na’ilah Nasir, Chair This dissertation is an intervention into Critical Whiteness Studies, an ‘additional movement’ to Ethnic Studies and Critical Race Theory. It systematically analyzes key contradictions in working against racism from a white subject positions under post-Civil Rights Movement liberal color-blind white hegemony and "Black Power" counter-hegemony through a critical assessment of two major competing projects in theory and practice: white anti-racism [Part 1] and New Abolitionism [Part 2]. I argue that while white anti-racism is eminently practical, its efforts to hegemonically rearticulate white are overly optimistic, tend toward renaturalizing whiteness, and are problematically dependent on collaboration with people of color. I further argue that while New Abolitionism has popularized and advanced an alternative approach to whiteness which understands whiteness as ‘nothing but oppressive and false’ and seeks to ‘abolish the white race’, its ultimately class-centered conceptualization of race and idealization of militant nonconformity has failed to realize effective practice. -

JPP 15-2-16-1 I-Viii

Preface Viviane Saleh-Hanna and Ashanti Omowali Alston n May 26, 2006, this issue of the Journal of Prisoners on Prisons was Oinitiated through the circulation of this letter: Journal of Prisoners on Prisons: A Special Black Panther Political Prisoners Issue Greeting Good People! This is a special invitation, from Ashanti Alston and Viviane Saleh-Hanna asking you to help us produce this Special Issue of the Journal of Prisoners on Prisons. It is dedicated to the Political Prisoners of the Black Panther Party and the Black Liberation Army. In the same spirit of this journal, this issue will be the words of the political prisoners themselves, along with those in exile and former political prisoners. For many, it has been over three decades of imprisonment in the face of mountainous fi les of Counter-Intelligence Program operations (federal/state/local) and present “Criminal-Justice” intransigence in setting these black revolutionary servants of the people free. Several of these servants have already “died” in prison—needlessly. How many more? Let this Special Issue contribute to highlighting Criminal-Justice in the United States of America and renewing our passion in fi ghting for the freedom of the political prisoners and for the completion of the revolutionary project of creating new world humanities. The Journal of Prisoners on Prisons (JPP) has worked for 15 years to bring forth the voices of prisoners, and has done a political prisoners issue in the past with revolutionaries in Ireland. Their 15th anniversary issue (published by the University of Ottawa Press) will be dedicated to the Black Panther Party and the Black Liberation Army. -

A Dramatic Exploration of Women and Their Agency in the Black Panther Party

Kennesaw State University DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University Master of Arts in American Studies Capstones Interdisciplinary Studies Department Spring 5-2017 Revolutionary Every Day: A Dramatic Exploration of Women and Their Agency in The lB ack Panther Party. Kristen Michelle Walker Kennesaw State University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/mast_etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, American Studies Commons, Playwriting Commons, Women's History Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Walker, Kristen Michelle, "Revolutionary Every Day: A Dramatic Exploration of Women and Their Agency in The lB ack Panther Party." (2017). Master of Arts in American Studies Capstones. 12. http://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/mast_etd/12 This Capstone is brought to you for free and open access by the Interdisciplinary Studies Department at DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Arts in American Studies Capstones by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REVOLUTIONARY EVERY DAY: A DRAMATIC EXPLORATION OF WOMEN AND THEIR AGENCY IN THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY A Creative Writing Capstone Presented to The Academic Faculty by Kristen Michelle Walker In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in American Studies Kennesaw State University May 2017 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction…………………………………...…………………………………………...……. -

N1 ROLL and FUCKING in the STREETS! RIGHT ON! WHITE

FREE NEWSPAPER OF WHITE PANTHER PARTY DOPE, ROCK 'n 1 ROLL 1510 HILL ST., A.A. AND FUCKING IN THE 769-2017 (L.S.D. phone, also) STREETS! RIGHT ON! White Panther News Service WHITE PANTHER NEWS SERVICE July 23, 1969 The pig power structure of this state has finally done what they have been trying to do for the past 3 years. They have put John Sinclair in jail. This morning in Recorder's Court, Judge Colombo sentenced John to 9g to 10 years in a state prison for the possession of less than 2 joints of marijuana. They think with this move, they will have crippled the American Liberation Movement in the medwest, and specifically the White Panther Party. This is where they have made their biggest mistake., just as the pig power structure made the mistake of putting Huey P. Newton in jail. When the California pigs, led by Mickey Mouse Reagan and Dpneld D'icfc Rafferty. put Huey in gail, tftey th'ought they wpuld be destroying the Black Panther Party, or at least reducing it to a level where it would no longer be functional. But their tactics backfired on them and today the Black Panther Party is the most respected of the revolutionary groups in Amerika, and also the most feared by the Pigs. The White Panther Party will grow and become stronger and more together than ever before. John Sinclair had a dream for this world, a dream where mankind could live together as brothers and not want for anything. A world where there was truly "freedom and justice for all," and out of this dream came the community known as Trans-tove, and out of Trans-Love came the White Panthers, and from the White Pantbeps- and all of the other revolutionary groups in this country, this dream will become reality, and the dreams of Jefferson, Thoreau, Mao, Che, Huey, and Eldridge will come to pass also. -

War Against the Panthers: a Study of Repression in America

War Against The Panthers: A Study Of Repression In America HUEY P. NEWTON / Doctoral Dissertation / UC Santa Cruz 1jun1980 WAR AGAINST THE PANTHERS: A STUDY OF REPRESSION IN AMERICA A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of: DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in HISTORY OF CONSCIOUSNESS by Huey P. Newton June 1980 PREFACE There has been an abundance of material to draw upon in researching and writing this dissertation. Indeed, when a friend recently asked me how long I had been working on it, I almost jokingly replied, "Thirteen years—since the Party was founded." 1 Looking back over that period in an effort to capture its meaning, to collapse time around certain significant events and personalities requires an admitted arbitrariness on my part. Many people have given or lost their lives, reputations, and financial security because of their involvement with the Party. I cannot possibly include all of them, so I have chosen a few in an effort to present, in C. Wright Mills' description, "biography as history." 2 This dissertation analyzes certain features of the Party and incidents that are significant in its development. Some central events in the growth of the Party, from adoption of an ideology and platform to implementation of community programs, are first described. This is followed by a presentation of the federal government's response to the Party. Much of the information presented herein concentrates on incidents in Oakland, California, and government efforts to discredit or harm me. The assassination of Fred Hampton, an important leader in Chicago, is also described in considerable detail, as are the killings of Alprentice "Bunchy" Carter and John Huggins in Los Angeles. -

Prelude by Safiya Bukhari 1950-2003

Jericho Manual The Movement to Free U.S. Political Prisoners & POW’s www.thejerichomovement.com 3rd Edition 2014 Table of Contents Prelude: Safiya Bukhari . 1 Jericho ’98: Herman Ferguson . 1 Definition of Political Prisoners and POWs . 3 Geneva Convention 1947 POWs . 3 Mission Statement . 3 Organizational Structure . 4 What Constitutes a Jericho Chapter . 5 Nominations & Elections & Procedures . 7 Practical Suggestions for Organizers . 8 Political Prisoners and POWS . 9 Appendix I: Historical Overview . .13 Afrikan Struggles . .12 Indigenous Struggles . .16 Puerto Rican Struggles . .19 European Dissidents . .20 Appendix II: Suggested Readings . .23 Appendix III: Jericho Chapters . .29 along those lines. But, the idea was clear, whatever we were attempting to do it began with education and it ended with liberation, or more precisely — educate to liberate! This manual helps us to educate the community and organize them in order to liberate our political prisoners and prisoners of war. Jericho is a movement — A movement with a Prelude by Safiya Bukhari 1950-2003 defined goal of getting recognition that political Sisters, Brothers, Comrades: prisoners exist inside the prisons of the United States, despite the government‘s denial; and Organizing and building support for our winning amnesty and freedom for these political prisoners, prisoners of war/captured political prisoners. While we are working to win combatants is and should be a monumental amnesty and freedom for these political part of our struggle. There should be no prisoners, we are demanding adequate problem with understanding how intricate this medical care for them and developing a legal work is to building a movement designed to win defense fund to insure legal representation as and not just exist. -

Ursula Mctaggart

RADICALISM IN AMERICA’S “INDUSTRIAL JUNGLE”: METAPHORS OF THE PRIMITIVE AND THE INDUSTRIAL IN ACTIVIST TEXTS Ursula McTaggart Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy In the Departments of English and American Studies Indiana University June 2008 Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Doctoral Committee ________________________________ Purnima Bose, Co-Chairperson ________________________________ Margo Crawford, Co-Chairperson ________________________________ DeWitt Kilgore ________________________________ Robert Terrill June 18, 2008 ii © 2008 Ursula McTaggart ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS A host of people have helped make this dissertation possible. My primary thanks go to Purnima Bose and Margo Crawford, who directed the project, offering constant support and invaluable advice. They have been mentors as well as friends throughout this process. Margo’s enthusiasm and brilliant ideas have buoyed my excitement and confidence about the project, while Purnima’s detailed, pragmatic advice has kept it historically grounded, well documented, and on time! Readers De Witt Kilgore and Robert Terrill also provided insight and commentary that have helped shape the final product. In addition, Purnima Bose’s dissertation group of fellow graduate students Anne Delgado, Chia-Li Kao, Laila Amine, and Karen Dillon has stimulated and refined my thinking along the way. Anne, Chia-Li, Laila, and Karen have devoted their own valuable time to reading drafts and making comments even in the midst of their own dissertation work. This dissertation has also been dependent on the activist work of the Black Panther Party, the League of Revolutionary Black Workers, the International Socialists, the Socialist Workers Party, and the diverse field of contemporary anarchists. -

The Black Power Movement. Part 2, the Papers of Robert F

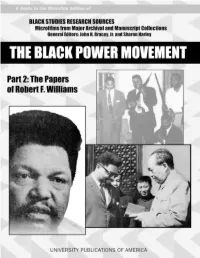

Cover: (Left) Robert F. Williams; (Upper right) from left: Edward S. “Pete” Williams, Robert F. Williams, John Herman Williams, and Dr. Albert E. Perry Jr. at an NAACP meeting in 1957, in Monroe, North Carolina; (Lower right) Mao Tse-tung presents Robert Williams with a “little red book.” All photos courtesy of John Herman Williams. A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of BLACK STUDIES RESEARCH SOURCES Microfilms from Major Archival and Manuscript Collections General Editors: John H. Bracey, Jr. and Sharon Harley The Black Power Movement Part 2: The Papers of Robert F. Williams Microfilmed from the Holdings of the Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan at Ann Arbor Editorial Adviser Timothy B. Tyson Project Coordinator Randolph H. Boehm Guide compiled by Daniel Lewis A microfilm project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of LexisNexis Academic & Library Solutions 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The Black power movement. Part 2, The papers of Robert F. Williams [microform] / editorial adviser, Timothy B. Tyson ; project coordinator, Randolph H. Boehm. 26 microfilm reels ; 35 mm.—(Black studies research sources) Accompanied by a printed guide compiled by Daniel Lewis, entitled: A guide to the microfilm edition of the Black power movement. Part 2, The papers of Robert F. Williams. ISBN 1-55655-867-8 1. African Americans—Civil rights—History—20th century—Sources. 2. Black power—United States—History—20th century—Sources. 3. Black nationalism— United States—History—20th century—Sources. 4. Williams, Robert Franklin, 1925— Archives. I. Title: Papers of Robert F. Williams. -

Black Panther Radical Factionalization and The

JBSXXX10.1177/0021934715593053Williams<italic>Journal of Black Studies</italic>Journal of Black Studies 593053research-article2015 Article Journal of Black Studies 2015, Vol. 46(7) 678 –703 Black Panther Radical © The Author(s) 2015 Reprints and permissions: Factionalization and the sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/0021934715593053 Development of Black jbs.sagepub.com Anarchism Dana M. Williams1 Abstract Racial justice social movements often fragment when their goals do not seem completely achievable. Former participants in the radical Black freedom struggles of the 1960s and 1970s, most of whom were Black Panther Party (BPP) members (and also participants in the Black Liberation Army) and identified with Marxist-Leninism, became disaffected with the hierarchical character of the Black Panthers and came to identify with anarchism. Through the lens of radical factionalization theories, Black anarchism is seen as a radical outgrowth of the Black freedom struggle. Black anarchists were the first to notably prioritize a race analysis in American anarchism. This tendency has a number of contemporary manifestations for anarchism, including Anarchist People of Color caucuses within the movement, and, more indirectly, the many anarchist strategies and organizations that share similarities with the BPP, prior to its centralization. Keywords Black Panthers, anarchism, Anarchist People of Color, Black anarchism, radical factionalization 1California State University, Chico, USA Corresponding Author: Dana M. Williams, Department of Sociology, California State University, 400 West First Street, Chico, CA 95929, USA. Email: [email protected] Downloaded from jbs.sagepub.com by guest on September 22, 2015 Williams 679 Introduction The Black freedom movement evolved in a variety of directions, but why did some former activists continue to radicalize as they witnessed movement failure? I focus on some of these activists who converged upon anarchist positions, only to discover that American anarchism was a largely White movement. -

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation

ABSTRACT Title of dissertation: SLAVE SHIPS, SHAMROCKS, AND SHACKLES: TRANSATLANTIC CONNECTIONS IN BLACK AMERICAN AND NORTHERN IRISH WOMEN’S REVOLUTIONARY AUTO/BIOGRAPHICAL WRITING, 1960S-1990S Amy L. Washburn, Doctor of Philosophy, 2010 Dissertation directed by: Professor Deborah S. Rosenfelt Department of Women’s Studies This dissertation explores revolutionary women’s contributions to the anti-colonial civil rights movements of the United States and Northern Ireland from the late 1960s to the late 1990s. I connect the work of Black American and Northern Irish revolutionary women leaders/writers involved in the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), Black Panther Party (BPP), Black Liberation Army (BLA), the Republic for New Afrika (RNA), the Soledad Brothers’ Defense Committee, the Communist Party- USA (Che Lumumba Club), the Jericho Movement, People’s Democracy (PD), the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA), the Irish Republican Socialist Party (IRSP), the National H-Block/ Armagh Committee, the Provisional Irish Republican Army (PIRA), Women Against Imperialism (WAI), and/or Sinn Féin (SF), among others by examining their leadership roles, individual voices, and cultural productions. This project analyses political communiqués/ petitions, news coverage, prison files, personal letters, poetry and short prose, and memoirs of revolutionary Black American and Northern Irish women, all of whom were targeted, arrested, and imprisoned for their political activities. I highlight the personal correspondence, auto/biographical narratives, and poetry of the following key leaders/writers: Angela Y. Davis and Bernadette Devlin McAliskey; Assata Shakur and Margaretta D’Arcy; Ericka Huggins and Roseleen Walsh; Afeni Shakur-Davis, Joan Bird, Safiya Bukhari, and Martina Anderson, Ella O’Dwyer, and Mairéad Farrell.