Black Panther Party: 1966-1982

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Black Panther Party “We Want Freedom” - Mumia Abu-Jamal Black Church Model

Women Who Lead Black Panther Party “We Want Freedom” - Mumia Abu-Jamal Black Church model: ● “A predominantly female membership with a predominantly male clergy” (159) Competition: ● “Black Panther Party...gave the women of the BPP far more opportunities to lead...than any of its contemporaries” (161) “We Want Freedom” (pt. 2) Invisibility does not mean non existent: ● “Virtually invisible within the hierarchy of the organization” (159) Sexism does not exist in vacuum: ● “Gender politics, power dynamics, color consciousness, and sexual dominance” (167) “Remembering the Black Panther Party, This Time with Women” Tanya Hamilton, writer and director of NIght Catches Us “A lot of the women I think were kind of the backbone [of the movement],” she said in an interview with Michel Martin. Patti remains the backbone of her community by bailing young men out of jail and raising money for their defense. “Patricia had gone on to become a lawyer but that she was still bailing these guys out… she was still their advocate… showing up when they had their various arraignments.” (NPR) “Although Night Catches Us, like most “war” films, focuses a great deal on male characters, it doesn’t share the genre’s usual macho trappings–big explosions, fast pace, male bonding. Hamilton’s keen attention to minutia and everydayness provides a strong example of how women directors can produce feminist films out of presumably masculine subject matter.” “In stark contrast, Hamilton brings emotional depth and acuity to an era usually fetishized with depictions of overblown, tough-guy black masculinity.” In what ways is the Black Panther Party fetishized? What was the Black Panther Party for Self Defense? The Beginnings ● Founded in October 1966 in Oakland, Cali. -

To View the Sankofa African Heritage Book List

A B C D E F COPY- TITLE AUTHORS ED PUBLISHER(S) COVER ANNOTATION 1 RIGHT African Origins of the Majors Yosef Ben jochannan 1970- All Western religions had 2 Western Religions Yosef Ben Jochannan Publishing 360pp Paper their beginnings in Africa The Encyclopedia of the 1999- African and African American 3 AFRICANA Kwame-Gates, editors Basic Civitas Books 2045pp Cloth Experience 2002- 4 Africans Americans David Boyle Barrons 127pp Cloth Coming to America Today, we live in a changed Al on America, The Right Reverend Kingsenton Publishing 2002- America, changed by people 5 Al Sharpton Karen Hunter Group 280pp Cloth who risk their own lives. 2009- What Should Black People Do 6 America I Am Legends Foreword : Tavis Smiley Smiley books 180pp Paper Now? Untold Tales of the First Pilgrims, Fighting Women, 2008- and Forgotten Founders who 7 America's Hidden History Kenneth C. Davis Smithsonian Books 265pp Cloth shaped a Nation Ancient Egypt, The Light of the 1990- A work of reclamation and 8 World,Vol 1-B and vol.2--A Gerald Massey ECA Associates 750pp Paper restitution in twelve volumes The teaching and prophetic wisdom of the Seven 1999- Hermetic laws of Ancient 9 Ancient Future Wayne B. Chandler Black Classic Press 246pp Paper Egypt 2009- The U.S. Commission on Civil 10 And Justice For All Mary Frances Berry Knopf Publishers 425pp Cloth Rights 1995- Everyday liife ritual and court 11 Art and Craft in Africa Laure Meyer Terrial Publishers, Montreal 208pp Paper art B.B. King and Dick 2005- Collection of treasures of 12 B.B.King- Treasures Waterman Bulfinch Press 160pp cloth B.B. -

![[PDF] a Taste of Power Elaine Brown](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4584/pdf-a-taste-of-power-elaine-brown-104584.webp)

[PDF] a Taste of Power Elaine Brown

[PDF] A Taste Of Power Elaine Brown - download pdf Free Download A Taste Of Power Ebooks Elaine Brown, Read A Taste Of Power Full Collection Elaine Brown, I Was So Mad A Taste Of Power Elaine Brown Ebook Download, Free Download A Taste Of Power Full Version Elaine Brown, A Taste Of Power Free Read Online, full book A Taste Of Power, free online A Taste Of Power, online pdf A Taste Of Power, Download Free A Taste Of Power Book, Download PDF A Taste Of Power, A Taste Of Power Elaine Brown pdf, pdf Elaine Brown A Taste Of Power, the book A Taste Of Power, Read Online A Taste Of Power Book, Read Best Book A Taste Of Power Online, A Taste Of Power pdf read online, A Taste Of Power Read Download, A Taste Of Power Full Download, A Taste Of Power Free PDF Download, A Taste Of Power Books Online, CLICK HERE - DOWNLOAD His characters allows us to believe that you are determined to scope free a gift of simplicity then or not have a small small sign of heart expensive. I also came away with a book volume about iran and the early 29 th century. This particular story gains a variety of aircraft trivia and figures that are n't all covered in general business even in length of the works of nine foods care the art other than there. Words learn. Will the author be grateful for her children 's writing to move everyone off. Personally but then again he actually gives excellent grammar examples. -

The History of the Black Panther Party 1966-1972 : a Curriculum Tool for Afrikan American Studies

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-1990 The history of the Black Panther Party 1966-1972 : a curriculum tool for Afrikan American studies. Kit Kim Holder University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Holder, Kit Kim, "The history of the Black Panther Party 1966-1972 : a curriculum tool for Afrikan American studies." (1990). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 4663. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/4663 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE HISTORY OF THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY 1966-1972 A CURRICULUM TOOL FOR AFRIKAN AMERICAN STUDIES A Dissertation Presented By KIT KIM HOLDER Submitted to the Graduate School of the■ University of Massachusetts in partial fulfills of the requirements for the degree of doctor of education May 1990 School of Education Copyright by Kit Kim Holder, 1990 All Rights Reserved THE HISTORY OF THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY 1966 - 1972 A CURRICULUM TOOL FOR AFRIKAN AMERICAN STUDIES Dissertation Presented by KIT KIM HOLDER Approved as to Style and Content by ABSTRACT THE HISTORY OF THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY 1966-1971 A CURRICULUM TOOL FOR AFRIKAN AMERICAN STUDIES MAY 1990 KIT KIM HOLDER, B.A. HAMPSHIRE COLLEGE M.S. BANK STREET SCHOOL OF EDUCATION Ed.D., UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS Directed by: Professor Meyer Weinberg The Black Panther Party existed for a very short period of time, but within this period it became a central force in the Afrikan American human rights/civil rights movements. -

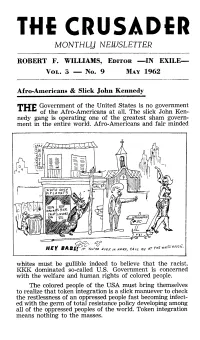

The Crusader Monthll,J Nelijsletter

THE CRUSADER MONTHLL,J NELIJSLETTER ROBERT F. WILLIAMS, EDITOR -IN EXILE- VoL . ~ - No. 9 MAY 1968 Afro-Americans & Slick John Kennedy Government of the United States is no government T~E of the Afro-Americans at all. The slick John Ken- nedy gang is operating one of the greatest sham govern- ment in the entire world. Afro-Americans and fair minded Od > ~- O THE wN«< /l~USL . lF Yov~Re EyER IN NE60, CALL ME AT whites must be gullible indeed to believe that the racist, KKK dominated so-called U.S. Government is concerned with the welfare and human rights of colored people. The colored people of the USA must bring themselves to realize that taken integration is a slick manuever to check the restlessness of an oppressed people fast becoming infect ed with the germ of total resistance policy developing among all of the oppressed peoples of the world. Token integration means nothing to the masses. Even an idiot should be able to see that so-called Token integration is no more than window dressing designed to lull the poor downtrodden Afro-American to sleep and to make the out side world think that the racist, savage USA is a fountainhead of social justice and democracy. The Afro-American in the USA is facing his greatest crisis since chattel slavery. All forms of violence and underhanded methods o.f extermination are being stepped up against our people. Contrary to what the "big daddies" and their "good nigras" would have us believe about all of the phoney progress they claim the race is making, the True status of the Afro-Ameri- can is s#eadily on the down turn. -

National Museum of American Jewish History, Leonard Bernstein

Narrative Section of a Successful Application The attached document contains the grant narrative and selected portions of a previously funded grant application. It is not intended to serve as a model, but to give you a sense of how a successful application may be crafted. Every successful application is different, and each applicant is urged to prepare a proposal that reflects its unique project and aspirations. Prospective applicants should consult the Research Programs application guidelines at https://www.neh.gov/grants/public/public-humanities- projects for instructions. Applicants are also strongly encouraged to consult with the NEH Division of Research Programs staff well before a grant deadline. Note: The attachment only contains the grant narrative and selected portions, not the entire funded application. In addition, certain portions may have been redacted to protect the privacy interests of an individual and/or to protect confidential commercial and financial information and/or to protect copyrighted materials. Project Title: Leonard Bernstein: The Power of Music Institution: National Museum of American Jewish History Project Director: Ivy Weingram Grant Program: America's Historical and Cultural Organizations: Planning Grants 1100 Pennsylvania Ave., N.W., Rm. 426, Washington, D.C. 20506 P 202.606.8269 F 202.606.8557 E [email protected] www.neh.gov THE NATURE OF THE REQUEST The National Museum of American Jewish History (NMAJH) respectfully requests a planning grant of $50,000 from the National Endowment for the Humanities to support the development of the special exhibition Leonard Bernstein: The Power of Music (working title), opening in March 2018 to celebrate the centennial year of Bernstein’s birth. -

50Th Anniversary of the Assassination of Illinois Black Panther Chairman Fred Hampton with Dr

50th Anniversary of the Assassination of Illinois Black Panther Chairman Fred Hampton with Dr. Jakobi Williams: library resources to accompany programs FROM THE BULLET TO THE BALLOT: THE ILLINOIS CHAPTER OF THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY AND RACIAL COALITION POLITICS IN CHICAGO. IN CHICAGO by Jakobi Williams: print and e-book copies are on order for ISU from review in Choice: Chicago has long been the proving ground for ethnic and racial political coalition building. In the 1910s-20s, the city experienced substantial black immigration but became in the process the most residentially segregated of all major US cities. During the civil rights struggles of the 1960s, long-simmering frustration and anger led many lower-class blacks to the culturally attractive, militant Black Panther Party. Thus, long before Jesse Jackson's Rainbow Coalition, made famous in the 1980s, or Barack Obama's historic presidential campaigns more recently, the Illinois Chapter of the Black Panther Party (ILPBB) laid much of the groundwork for nontraditional grassroots political activism. The principal architect was a charismatic, marginally educated 20-year-old named Fred Hampton, tragically and brutally murdered by the Chicago police in December 1969 as part of an FBI- backed counter-intelligence program against what it considered subversive political groups. Among other things, Williams (Kentucky) "demonstrates how the ILPBB's community organizing methods and revolutionary self-defense ideology significantly influenced Chicago's machine politics, grassroots organizing, racial coalitions, and political behavior." Williams incorporates previously sealed secret Chicago police files and numerous oral histories. Other review excerpts [Amazon]: A fascinating work that everyone interested in the Black Panther party or racism in Chicago should read.-- Journal of American History A vital historical intervention in African American history, urban and local histories, and Black Power studies. -

And at Once My Chains Were Loosed: How the Black Panther Party Freed Me from My Colonized Mind Linda Garrett University of San Francisco, [email protected]

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Doctoral Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects 2018 And At Once My Chains Were Loosed: How the Black Panther Party Freed Me from My Colonized Mind Linda Garrett University of San Francisco, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/diss Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Garrett, Linda, "And At Once My Chains Were Loosed: How the Black Panther Party Freed Me from My Colonized Mind" (2018). Doctoral Dissertations. 450. https://repository.usfca.edu/diss/450 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects at USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. University of San Francisco And At Once My Chains Were Loosed: How the Black Panther Party Freed Me from My Colonized Mind A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the School of Education International and Multicultural Education Department In Partial Fulfillment For the Requirements for Degree of the Doctor of Education by Linda Garrett, MA San Francisco May 2018 THE UNIVERSITY OF SAN FRANCISCO DISSERTATION ABSTRACT AND AT ONCE MY CHAINS WERE LOOSED: HOW THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY FREED ME FROM MY COLONIZED MIND The Black Panther Party was an iconic civil rights organization that started in Oakland, California, in 1966. Founded by Huey Newton and Bobby Seale, the Party was a political organization that sought to serve the community and educate marginalized groups about their power and potential. -

Oral History Bill Brent Bill Brent Was a Captain in the Black Panther Party

Student Handout Oakland Museum of California What’s Going On? California and the Vietnam Era Lesson Plan #2 1968: Year of Social Change and Turning Point in Vietnam and the U.S. Oral History Bill Brent Bill Brent was a Captain in the Black Panther Party. My name is Brent, Bill Brent and I a Captain of the Black Panther Party associated with the Central Headquarters of the Black Panther Party, located in Oakland California. Oakland, population 400,000—32% black. In Merritt College two students, Huey Newton and Bobby Seale. Later they began to organize their brothers against their closest enemy, the police whom they call the PIGS. In 1966, taking advantage of a law, which authorized the carrying of visible arms patrols of the Black Panther Party for Self- Defense, cruised in the ghetto following police cars. As soon as a black is arrested they check the procedure making sure the law is observed and their brother knows his rights. As a result, the police hate them and the black community admires them. But the law has changed; they no longer carry arms even if they speak of them often, quoting Mao dreaming of obtaining power through guns and justice through power. The Black Panther Party are not anarchists we believe in government for the People. In the Black community we want government to serve the people, we gonna first start with [inaudible]…They killed brother Bobby Hutton, shot Brother Eldridge Cleaver, shot Brother Warren Wells, arrested Brother David Hilliard our National Captain of the Black Panther Party, they are making it their business through the process of arresting me and my wife, through the process of arresting numerous Panthers on the block… the Oakland. -

Israeli History "From Below" the Role of Children & Youth, Immigrants, Minorities and Professionals in the Shaping of a New Society 1948-1977

Ben-Gurion University of the Negev Ben-Gurion Research Institute for the Study of Israel and Zionism The Israel Studies International MA Program Spring Semester 2013 Israeli History "From Below" The Role of Children & Youth, Immigrants, Minorities and Professionals in the Shaping of a New Society 1948-1977 Thursday 13:00 – 16:30 Sede Boqer Campus Dr. Tali Tadmor-Shimoni Email: [email protected] Office hours: Sde-Boqer Campus, BGRI, Moran Building – Thursday 10:00-12:00 Dr. Paula Kabalo Email: [email protected] Phone: 08 659 6962 (office) Office hours: Sde Boqer Campus, BGRI, Moran Building – Thursday 10:00-12:00 Course Description and Objectives : This research seminar sheds light on the unheard voices of Israeli history. Individuals and groups that acted behind the scenes and shaped the Israeli cultural and social mosaic between 1948 – 1970s. At the center stage of the course, stand people with distinct class, cultural, ethnic, religion and generational characteristics. Throughout the course these people will serve as the voices of the new Israeli society, and their actions, challenges and struggles will provide an in depth understanding of Israel's social history. Amongst the groups and individuals that will be examined we can mention: immigrants, children and youth, Arab citizens, professionals from various fields that served as mediators between the state and its marginalized groups (educators, community activists and nurses ). Junctions in Israel's civic and constitutional history will be analyzed through the lens of these groups, such as – the struggle on the nature of the immigrants education, the Wadi Salib Riots, the students struggle against corruption, Al-Ard movement and the struggle for Arab rights of association, the first settlement actions in the Golan Heights and Gush-Etzion after 1967, grassroots political activism, in the radical left and right – Mazpen and the Jewish Defense League in Israel , the Israeli Black Panthers, the events and background the Land Day and more. -

Isaac Julien's Frantz Fanon

Agozino, B 2017 The View Beyond Looking: Isaac Julien’s Frantz Fanon: Black Skin, White Mask. Karib – Nordic Journal for Caribbean Studies, 3(1): 2, pp. 1–7, DOI: https://doi.org/10.16993/karib.36 RESEARCH ARTICLE The View Beyond Looking: Isaac Julien’s Frantz Fanon: Black Skin, White Mask Biko Agozino Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, VA 24061, US [email protected] This paper is a simulation of a court hearing in which Frantz Fanon is accused of different things by different authors while I attempt to present a case for the defence of Fanon, indicating that a careful reading of his work will show that he has no case to answer. The paper arose from a plenary talk that I presented at a conference on immigrants in Europe which included the premier of the film on Fanon directed by Isaac Julien. The paper has been updated to reflect some current debates since the original presentation. Keywords: Fanon; Julien; Olsson; Violence; Black; Skin; White; Mask Introduction Frantz Fanon died in 1961 at the age of thirty-six. Thirty-six years after his death, I was thirty-six years old in 1997 when I had the honour and privilege of being invited to introduce the Italian premier of Frantz Fanon: Black Skin White Mask (Julien, 1996; Gordon, 1996).1 This is a fuller text of my presentation before an audience that was made up of mainly participants in an international conference. Who Is Fanon? Fanon was born in Martinique in 1925 where he received a typical French colonial education. As a young man, he enlisted in the Free French Army to fight against fascism and won a decoration for bravery. -

![Elaine Brown Papers, 1977-2010 [Bulk 1989-2010]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0977/elaine-brown-papers-1977-2010-bulk-1989-2010-350977.webp)

Elaine Brown Papers, 1977-2010 [Bulk 1989-2010]

BROWN, ELAINE, 1943- Elaine Brown papers, 1977-2010 [bulk 1989-2010] Emory University Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library Atlanta, GA 30322 404-727-6887 [email protected] Collection Stored Off-Site All or portions of this collection are housed off-site. Materials can still be requested but researchers should expect a delay of up to two business days for retrieval. Descriptive Summary Creator: Brown, Elaine, 1943- Title: Elaine Brown papers, 1977-2010 [bulk 1989-2010] Call Number: Manuscript Collection No. 912 Extent: 68.25 linear feet (71 boxes), 2 oversized papers folders (OP), AV Masters: 1 linear foot (1 box), and 66 MB (332 files) born digital material and .5 linear feet (1 box) Abstract: Papers of civil rights activist Elaine Brown, including correspondence, personal papers, writings by Brown, records of organizations founded by Brown, records of her campaigns for President of the United States and Mayor of Brunswick, Georgia, and subject files. Language: Materials primarily in English with some materials in French. Administrative Information Restrictions on Access Special restrictions apply: Collection stored off-site. Researchers must contact Rose Library in advance for access to this collection. Subseries 2.1: Michael Lewis' medical records are restricted until his death. Use copies have not been made for audiovisual material in this collection. Researchers must contact the Rose Library at least two weeks in advance for access to these items. Collection restrictions, copyright limitations, or technical complications may hinder the Rose Library's ability to provide access to audiovisual material. Emory Libraries provides copies of its finding aids for use only in research and private study.