The Statuary Collection Held at the Baths of Zeuxippus (AP 2) and the Search for Constantine’S Museological Intentions Synthesis, Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Graham Jones

Ni{ i Vizantija XIV 629 Graham Jones SEEDS OF SANCTITY: CONSTANTINE’S CITY AND CIVIC HONOURING OF HIS MOTHER HELENA Of cities and citizens in the Byzantine world, Constantinople and its people stand preeminent. A recent remark that the latter ‘strove in everything to be worthy of the Mother of God, to Whom the city was dedicated by St Constantine the Great in 330’ follows a deeply embedded pious narrative in which state and church intertwine in the city’s foundation as well as its subse- quent fortunes. Sadly, it perpetuates a flawed reading of the emperor’s place in the political and religious landscape. For a more nuanced and considered view we have only to turn to Vasiliki Limberis’ masterly account of politico-religious civic transformation from the reign of Constantine to that of Justinian. In the concluding passage of Divine Heiress: The Virgin Mary and the Creation of Christianity, Limberis reaffirms that ‘Constantinople had no strong sectarian Christian tradition. Christianity was new to the city, and it was introduced at the behest of the emperor.’ Not only did the civic ceremonies of the imperial cult remain ‘an integral part of life in the city, breaking up the monotony of everyday existence’. Hecate, Athena, Demeter and Persephone, and Isis had also enjoyed strong presences in the city, some of their duties and functions merging into those of two protector deities, Tyche Constantinopolis, tutelary guardian of the city and its fortune, and Rhea, Mother of the Gods. These two continued to be ‘deeply ingrained in the religious cultural fabric of Byzantium.. -

I Ntroduction

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-77257-0 - Byzantine Monuments of Istanbul John Freely and Ahmet S. Cakmak Excerpt More information _ I NTRODUCTION his is the story of the Byzantine monuments of Istanbul, the city known to Tthe Greeks as Constantinople, the ancient Byzantium. Constantinople was, for more than a thousand years, capital of the Byzantine Empire, which in its earlier period, from the fourth to the sixth century,was synonomous with the Roman Empire. During those centuries, the religion of the empire changed from pagan to Christian and its language from Latin to Greek, giving rise to the cul- ture that in later times was called Byzantine, from the ancient name of its capital. As the great churchman Gennadius was to say in the mid-fifteenth century,when the empire had come to an end,“Though I am a Hellene by speech yet I would never say that I was a Hellene, for I do not believe as Hellenes believe. I should like to take my name from my faith, and if anyone asks me what I am, I answer, ‘A Christian.’Though my father dwelt in Thessaly, I do not call myself a Thes- salian, but a Byzantine, for I am of Byzantium.”1 The surviving Byzantine monuments of Istanbul include more than a score of churches, most notably Hagia Sophia. Other extant monuments include the great land walls of the city and fragments of its sea walls; the remains of two or three palaces; a fortified port; three commemorative columns and the base of a fourth; two huge subterranean cisterns and several smaller ones; three enormous reservoirs; an aqueduct; a number of fragmentary ruins; and part of the Hippo- drome, the city’s oldest monument and the only one that can surely be assigned to ancient Byzantium. -

Notitia Urbis Constantinopolitanae

The Notitia Urbis Constantinopolitanae University Press Scholarship Online Oxford Scholarship Online Two Romes: Rome and Constantinople in Late Antiquity Lucy Grig and Gavin Kelly Print publication date: 2012 Print ISBN-13: 9780199739400 Published to Oxford Scholarship Online: May 2012 DOI: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199739400.001.0001 The Notitia Urbis Constantinopolitanae John Matthews DOI:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199739400.003.0004 Abstract and Keywords The first English translation of the Notitia Urbis Constantinopolitanae, a crucial source for understanding the topography and urban development of early Constantinople, is presented here. This translation is accompanied, first, by an introduction to the text, and then by detailed discussion of the fourteen Regions, and finally by a conclusion, assessing the value of the evidence provided by this unique source. The discussion deals with a number of problems presented by the Notitia, including its discrepancies and omissions. The Notitia gives a vivid picture of the state of the city and its population just after its hundredth year: still showing many physical traces of old Byzantium, blessed with every civic amenity, but not particularly advanced in church building. The title Urbs Constantinopolitana nova Roma did not appear overstated at around the hundredth year since its foundation. Keywords: Byzantium, Constantinople, topography, Notitia, urban development, regions, Notitia Urbis Constantinopolitanae Page 1 of 50 PRINTED FROM OXFORD SCHOLARSHIP ONLINE (www.oxfordscholarship.com). (c) Copyright Oxford University Press, 2017. All Rights Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a monograph in OSO for personal use (for details see http://www.oxfordscholarship.com/page/privacy-policy). -

Byzantion, Zeuxippos, and Constantinople: the Emergence of an Imperial City

Constantinople as Center and Crossroad Edited by Olof Heilo and Ingela Nilsson SWEDISH RESEARCH INSTITUTE IN ISTANBUL TRANSACTIONS, VOL. 23 Table of Contents Acknowledgments ......................................................................... 7 OLOF HEILO & INGELA NILSSON WITH RAGNAR HEDLUND Constantinople as Crossroad: Some introductory remarks ........................................................... 9 RAGNAR HEDLUND Byzantion, Zeuxippos, and Constantinople: The emergence of an imperial city .............................................. 20 GRIGORI SIMEONOV Crossing the Straits in the Search for a Cure: Travelling to Constantinople in the Miracles of its healer saints .......................................................... 34 FEDIR ANDROSHCHUK When and How Were Byzantine Miliaresia Brought to Scandinavia? Constantinople and the dissemination of silver coinage outside the empire ............................................. 55 ANNALINDEN WELLER Mediating the Eastern Frontier: Classical models of warfare in the work of Nikephoros Ouranos ............................................ 89 CLAUDIA RAPP A Medieval Cosmopolis: Constantinople and its foreigners .............................................. 100 MABI ANGAR Disturbed Orders: Architectural representations in Saint Mary Peribleptos as seen by Ruy González de Clavijo ........................................... 116 ISABEL KIMMELFIELD Argyropolis: A diachronic approach to the study of Constantinople’s suburbs ................................... 142 6 TABLE OF CONTENTS MILOŠ -

Anastasius I As Pompey Brian Croke

Poetry and Propaganda: Anastasius I as Pompey Brian Croke NASTASIUS I (491–518) was blessed with panegyrists to sing the praises of an aged emperor, and the laudatory A contributions of three of them survive: Christodorus of Coptos, Procopius of Gaza, and Priscian of Caesarea. One of the themes in their propaganda was the promotion of a link be- tween the emperor and the Roman general Pompey whose de- cisive victories in the 60s B.C. finally secured Roman authority in Asia Minor and the east. The notion was advanced and echoed that the emperor was descended from the Republican general and that his military victories over the Isaurians in southern Asia Minor in the 490s made him a modern Pompey. This propaganda motif has never been explored and explained. The public connection between Pompey and Anastasius de- pended on the awareness of Pompey’s eastern conquests by emperor, panegyrist, and audience alike. At the Megarian colony of Byzantium, so it is argued here, commemorative statues and inscriptions were erected to the victorious Pompey in 62/1 B.C. and they still existed in the sixth century Roman imperial capital which the city had now become. Moreover, these Pompeian memorials provided the necessary familiarity and impetus for Anastasian propaganda in the wake of the Isaurian war. 1. Celebrating Anastasius’ Isaurian victory Early Byzantine emperors were “ever victorious.” Victory was a sign of God’s favour and accompanied all the emperor’s movements and campaigns.1 Rarely, however, did the Byzan- tines experience the commemoration of a real imperial military 1 M. -

IV in Ravenna-Classe, Lower-Class Apartments in the Harbor Area of The

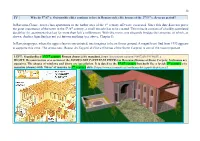

38 IV Why do 5th/6th c. Ostrogothic elites continue to live in Roman-style elite houses of the 2nd/3rd c. Severan period? In Ravenna-Classe, lower-class apartments in the harbor area of the 1st century AD were excavated. Since this date does not prove the great importance of the town in the 5th/6th century, a small miracle has to be created. This miracle consists of a boldly postulated durability for apartments that last for more than half a millennium. With this move, one elegantly bridges the centuries, of which, as shown, Andrea Agnellus has not yet known anything (see above, Chapter I). In Ravenna proper, where the upper class is concentrated, one imagines to be on firmer ground. A magnificent find from 1993 appears to supports this view. The aristocratic Domus dei Tappeti di Pietra (Domus of the Stone Carpets) is one of the most important LEFT: Standardized 1st/2nd century Roman domus (city mansion). [https://pl.pinterest.com/pin/91057223699970657/.] RIGHT: Reconstruction of a section of the DOMUS DEI TAPPETI DI PIETRA in Ravenna (Domus of Stone Carpets; bedrooms are upstairs). The shapes of windows and doors are speculation. It is dated to the 5th/6th century but built like a lavish 2nd century city mansion (domus) with 700 m2 of mosaics in 2nd century style. [https://www.ravennantica.it/en/domus-dei-tappeti-di-pietra-ra/.] 39 Italian archaeological sites discovered in recent decades. Located inside the eighteenth-century Church of Santa Eufemia, in a vast underground environment located about 3 meters below street level, it consists of 14 rooms paved with polychrome mosaics and marble belonging to a private building of the fifth-sixth century. -

Constantinople: the Rise of a New Capital in the East

Constantinople: The Rise of a New Capital in the East HANS-GEORG BECK* CONSTANTINOPLE and her splendor: a fascinating and almost misleading topic; so fascinating that not a few Byzantinists and art historians, praising the glory of the city, apparently forget some essential laws of history-for example, that even the rise of Constantinople must have taken time, that it did not burst forth with Constantine the Great, pacing the far-reaching new circuit of his foundation under divine guidance. And there are other scholars who ask if it is really true that this city, from its beginnings, was radiating, that from its beginnings it was the pivot of politics, the center of art and erudition, and the source of Christian life in the East. The validity of the question is self-evident.1 Rome was not built in a day; nor was Constantinople, though it is surprising how rapidly she developed into a big city of worldwide importance. For some of the local Byzantine historians this development approaches a wonder. But the wonder may be reduced to a less miraculous dimension by taking into consideration that Constantine's city was built on older foundations. Forgetting the fabulous city of the ancient King Byzas and the Megarean Byzantion, let us turn to the important events that took place in the reign of the Roman emperor Septimius Severnus.2 It is true that in 196 he destroyed the old Byzantion because she had fought on the wrong political side. But soon after this catastrophe, the emperor realized the outstanding value of the city's geographical location in the midst of a new political constellation.3 Septimius Severus and his successors therefore began to rebuild the city and to give her quite a different, almost an imperial, dimension. -

Table of Contents

The Sundered Eagle Contents The Middle Classes ........................ 37 I. Introduction 6 III. The Order of Hermes 20 The Lower Classes .......................... 37 BYZANTINE LANDSCAPE ....................... 6 HERMETIC HISTORY .......................... 20 Slavery ............................................ 37 BYZANTINE REALMS ............................ 6 Before the Order of Hermes ........... 20 Eunuchs .......................................... 37 BYZANTINE PEOPLES ........................... 6 Shaping the Theban Tribunal ......... 20 Women ........................................... 38 BYZANTINE LEGENDS .......................... 6 The Collapse of an Empire .................22 THE EASTERN CHURCH ..................... 38 HOW TO USE THIS BOOK ................... 7 THE LEAGUES OF THEBES .................. 22 The Two Patriarchs The League of Constantine ............ 22 of Constantinople ........................... 38 The Children of Olympos .............. 23 Buildings ......................................... 39 II. History of the Empire 8 The League of the Vigilant ............. 24 Clergy ............................................. 39 League Against Idolatry .................. 24 The Origin of Mankind .................... 8 Monastics ....................................... 40 The Age of Heroes ........................... 8 THEBAN TRIBUNAL POLITICS .............. 24 Icons ............................................... 40 The Trojan War .................................8 THE HERMETIC POLITY ..................... 24 INHABITANTS................................... -

The Statuary Collection Held at the Baths of Zeuxippus (Ap 2) and the Search for Constantine's Museological Intentions

Martins de Jesus, Carlos A. The statuary collection held at the baths of Zeuxippus (Ap 2) and the search for Constantine's museological intentions Synthesis 2014, vol. 21 CITA SUGERIDA: Martins de Jesus, C. A. (2014). The statuary collection held at the baths of Zeuxippus (Ap 2) and the search for Constantine's museological intentions. Synthesis, 21. En Memoria Académica. Disponible en: http://www.memoria.fahce.unlp.edu.ar/art_revistas/pr.6391/pr.6391.pdf Documento disponible para su consulta y descarga en Memoria Académica, repositorio institucional de la Facultad de Humanidades y Ciencias de la Educación (FaHCE) de la Universidad Nacional de La Plata. Gestionado por Bibhuma, biblioteca de la FaHCE. Para más información consulte los sitios: http://www.memoria.fahce.unlp.edu.ar http://www.bibhuma.fahce.unlp.edu.ar Esta obra está bajo licencia 2.5 de Creative Commons Argentina. Atribución-No comercial-Sin obras derivadas 2.5 The statuary collection held at the baths of Zeuxippus (Ap 2) and the search for Constantine’s museological intentions Carlos A. Martins de Jesus Synthesis, vol. 21, 2014. ISSN 1851-779X http://www.synthesis.fahce.unlp.edu.ar/ ARTICULO/ARTICLE The statuary collection held at the baths of Zeuxippus (AP 2) and the search for Constantine’s museological intentions1 Carlos A. Martins de Jesus University of Coimbra; University Complutense of Madrid, FCT Portugal; España Cita sugerida: Martins de Jesus, C. A. (2014). The statuary collection held at the baths of Zeuxippus (AP 2) and the search for Constantine’s museological intentions. Synthesis, 21. Recuperado de: http://www.synthesis.fahce.unlp.edu.ar/article/view/5412 Resumen Constantino pretendía enseñar al mundo su Constantinopla como la Nueva (la tercera) Troya, el más acabado retrato de la nueva paidea de inspiración griega y romana. -

Messianic Jerusalem and the Myth of an Imperial City in Late Antiquity

MESSIANIC JERUSALEM AND THE MYTH OF AN IMPERIAL CITY IN LATE ANTIQUITY Alexei SIVERTSEV DePaul University (Chicago, USA) [email protected] In a recent study, Ra’anan S. Boustan has provided a detailed analysis of the story of temple vessels in what appears to be one of the earlier redactions of ‘Otot ha- Mashiah, a late antique Jewish text describing the signs of Messiah’s arrival, and this story’s relation to a broader literary motif of temple spoils kept in Rome1. As noted by Boustan, this redaction of ‘Otot ha-Mashiah displays no knowledge of a confrontation between Christian Byzantium and Islam. Instead the eschatologi cal struggle takes place strictly between Jews and Rome. Already in the opening sections of the text the latter is portrayed as the ultimate persecutor of Jews and Judaism. The sixth sign thSt contains the story about Temple vessels constitutes the culmination of the struggle between the two. A king rules in Rome for nine months, during which time he devastates numerous lands, levies heavy taxes upon Israel, and promulgates numerous decrees against it. After nine months Nehemiah son of Hushiel, the Messiah son of Joseph, is revealed. He launches a war against the king of Edom: The Messiah son of Joseph will come and wage war against the king of Edom. He will win a victory against Edom and kill heaps and mounds of them. He will kill the king of Edom and lay waste the province of Rome. He will take out some of the Temple vessels which are hidden in the palace of Julianos Caesar2 and come to Jerusalem. -

Baths of Zeuxippos

IΔΡΥΜA ΜΕΙΖΟΝΟΣ ΕΛΛΗΝΙΣΜΟΥ Συγγραφή : Μαρίνης Βασίλειος (20/7/2008) Για παραπομπή : Μαρίνης Βασίλειος , "Baths of Zeuxippos", 2008, Εγκυκλοπαίδεια Μείζονος Ελληνισμού, Κωνσταντινούπολη URL: <http://www.ehw.gr/l.aspx?id=12457> Baths of Zeuxippos Περίληψη : The Baths of Zeuxippos were located by the northeastern corner of the Hippodrome and close to the Augusteion and the Great Palace. Septimius Severus is credited with their construction. The baths were enlarged by Constantine I in the 4th century. They were decorated with numerous statues of gods, mythological heroes, and portraits of famous Greeks and Romans. Destroyed in the 6th century, the Baths of Zeuxippos were rebuilt by Justinian I. Parts of the complex were subsequently converted into a prison; another section functioned as a silk workshop. Χρονολόγηση late 2nd - 9th (?) c. Γεωγραφικός εντοπισμός Constantinople, Istanbul 1. History The Baths of Zeuxippos were located by the northeastern corner of the Hippodrome and close to the Augustaion and the Great Palace. Byzantine sources attribute their construction to Septemius Severus (end of the 2nd century AD). Constantine I enlarged and redecorated the complex. The baths were destroyed by fire in 532 and were subsequently rebuilt by Justinian. They might have been functioning up to the 9th century. Thereafter, parts of the building became a prison, known under the name Noumera, while another part was converted to a silk workshop. The Baths of Zeuxippos have all but disappeared today. Parts of the bath proper along with parts of a large peristyle that flanked it to the east, probably of Justinianic date, were unearthed in 1927 and 1928.1 During these excavations three statue bases (two bearing inscriptions with the names of the statues they originally supported) and a much-mutilated fragment of a colosal female head were uncovered. -

Virtue from Necessity in the Urban Waterworks of Roman Asia Minor

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Virtue from Necessity in the Urban Waterworks of Roman Asia Minor A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History of Art and Architecture by Brianna Lynn Bricker Committee in charge: Professor Fikret K. Yegül, Chair Professor Swati Chattopadhyay Professor Christine M. Thomas June 2016 The dissertation of Brianna Lynn Bricker is approved: ____________________________________________ Swati Chattopadhyay ____________________________________________ Christine M. Thomas ____________________________________________ Fikret K. Yegül, Committee Chair June 2016 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Damlaya damlaya göl olur “Drop by drop, a lake will form,” goes the Turkish proverb. And so went this dissertation project: little by little quotidian efforts turned into something larger. But these drops, in fact, were not just my own efforts, nor were they always quotidian. The number of drops contributed by others is incalculable, but the impact is clear. Special thanks go to my advisor Fikret Yegül for his unwavering support and kindness throughout my graduate school experience. I also thank Diane Favro for her continual warmth and helpfulness. I am deeply thankful for my other committee members, Swati Chattopadhyay and Christine Thomas, for providing important outside perspectives and challenging me to go farther with my work. I am truly grateful for my community at UCSB: firstly, the Department of the History of Art and Architecture, for the support and space to grow as a scholar. I also thank the Ancient Borderlands Research Focus Group for fostering collaboration between disciplines and creating an inviting and dynamic atmosphere of research. I would particularly like to thank my community at the Sardis Expedition, for nurturing in me the curiosity and zeal to explore the Anatolian countryside: Marcus Rautman introduced me to the intricacies and interesting nature of waterworks, while Bahadır Yıldırım and Nicholas Cahill provided further encouragement and perspective.