Braund 1993.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction: Medea in Greece and Rome

INTRODUCTION: MEDEA IN GREECE AND ROME A J. Boyle maiusque mari Medea malum. Seneca Medea 362 And Medea, evil greater than the sea. Few mythic narratives of the ancient world are more famous than the story of the Colchian princess/sorceress who betrayed her father and family for love of a foreign adventurer and who, when abandoned for another woman, killed in revenge both her rival and her children. Many critics have observed the com plexities and contradictions of the Medea figure—naive princess, knowing witch, faithless and devoted daughter, frightened exile, marginalised alien, dis placed traitor to family and state, helper-màiden, abandoned wife, vengeful lover, caring and filicidal mother, loving and fratricidal sister, oriental 'other', barbarian saviour of Greece, rejuvenator of the bodies of animals and men, killer of kings and princesses, destroyer and restorer of kingdoms, poisonous stepmother, paradigm of beauty and horror, demi-goddess, subhuman monster, priestess of Hecate and granddaughter of the sun, bride of dead Achilles and ancestor of the Medes, rider of a serpent-drawn chariot in the sky—complex ities reflected in her story's fragmented and fragmenting history. That history has been much examined, but, though there are distinguished recent exceptions, comparatively little attention has been devoted to the specifically 'Roman' Medea—the Medea of the Republican tragedians, of Cicero, Varro Atacinus, Ovid, the younger Seneca, Valerius Flaccus, Hosidius Geta and Dracontius, and, beyond the literary field, the Medea of Roman painting and Roman sculp ture. Hence the present volume of Ramus, which aims to draw attention to the complex and fascinating use and abuse of this transcultural heroine in the Ro man intellectual and visual world. -

Latin Literature 1

Latin Literature 1 Latin Literature The Project Gutenberg EBook of Latin Literature, by J. W. Mackail Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this or any other Project Gutenberg eBook. This header should be the first thing seen when viewing this Project Gutenberg file. Please do not remove it. Do not change or edit the header without written permission. Please read the "legal small print," and other information about the eBook and Project Gutenberg at the bottom of this file. Included is important information about your specific rights and restrictions in how the file may be used. You can also find out about how to make a donation to Project Gutenberg, and how to get involved. **Welcome To The World of Free Plain Vanilla Electronic Texts** **eBooks Readable By Both Humans and By Computers, Since 1971** *****These eBooks Were Prepared By Thousands of Volunteers!***** Title: Latin Literature Author: J. W. Mackail Release Date: September, 2005 [EBook #8894] [Yes, we are more than one year ahead of schedule] [This file was first posted on August 21, 2003] Edition: 10 Latin Literature 2 Language: English Character set encoding: ISO−8859−1 *** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK LATIN LITERATURE *** Produced by Distributed Proofreaders LATIN LITERATURE BY J. W. MACKAIL, Sometime Fellow of Balliol College, Oxford A history of Latin Literature was to have been written for this series of Manuals by the late Professor William Sellar. After his death I was asked, as one of his old pupils, to carry out the work which he had undertaken; and this book is now offered as a last tribute to the memory of my dear friend and master. -

Latm Literature

PR EFA CE . A HISTORY of Latin Literature was to have been written for this series of Manuals by the late Professor William S . A I ellar fter his death was asked, as one of his old h pupils, to carry out the work which e had undertaken ; and this book is now offered as a last tribute to the memory of my dear friend and master. M. J . W. CO NT ENT S . Andronicus and Naevius Ennius Pacuvius Dec ay ‘ The Ear ly j ur ists Cato The Sc ipionic Circ l e r Lru Cinna and Cal vus Cle f-mo PAGE ’ ‘ PRO ERTI US AND THE ELEGI SI S . III . P - T bu us Augustan Trage dy Callus Prope rtius i ll m I V. Ov . Juli a and Sulpic ia Ovid VY V . LI TANs. VI . THE LESSER AuGUS —Tro Minor Aug ustan Poetry Manilius Phae dr us gus and Pate rculus Ce lsus The Elder Se ne ca THE EMPI RE. LUCA PET RONI Us . THE ROME OF NERO : SENECA, N , Se neca Lucan Pe rsius Col um e lla Pe tronius VE GE S US THE ELDER P Y MAR THE SI L R A : TATI , LIN , U . TIAL, Q INTILIAN — — — Stati us Silius I talic us Martial The Elde r Pliny —~ Qui ntilian TACI TUs III . ’ UVENAL TH E YOUNGER P Y SUEI‘O NI US : DECA or I V. J , LIN , Y CLASSI CAL L ATIN . — Juve nal The Younge r Pliny Sue tonius Aul us C e llins “ ” THE ELOCUTI O NOVELLA. -

Grammar and Poetry in the Late Republic

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2014 The Way That Our Catullus Walked: Grammar and Poetry in the Late Republic Samuel David Beckelhymer University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Classics Commons Recommended Citation Beckelhymer, Samuel David, "The Way That Our Catullus Walked: Grammar and Poetry in the Late Republic" (2014). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 1205. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1205 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1205 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Way That Our Catullus Walked: Grammar and Poetry in the Late Republic Abstract This dissertation considers the poetry of Catullus and its often express concerns with matters of language through the lens of the Roman grammatical tradition. I argue that in Latin poetry, and in Latin literature more broadly, there existed a persistent interest in discussing linguistic matters--owing in large part to an early imitation of Greek authors who engaged openly with their language--and that this interest was articulated in ways that recall the figure of the professional grammaticus and the ars grammatica, the scientific study of the Latin language. I maintain that this interest becomes particularly widespread during the final decades of the Roman Republic, and so I present Catullus as a particularly representative example of this phenomenon. In each chapter I examine Catullus' poetry with reference to a different aspect of the grammaticus' trade. The first chapter considers the concept of latinitas, an idealized form of Latin that was discussed by professional grammatici, and coordinates Catullus' interaction with foreign words, morphology and phonology with similar approaches to the discussion of language as they are expressed by other poets and prose authors. -

7.5 X 11 Long Title.P65

Cambridge University Press 0521837499 - The Etymologies of Isidore of Seville Stephen A. Barney, W. J. Lewis, J. A. Beach and Oliver Berghof Index More information INDEX © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 0521837499 - The Etymologies of Isidore of Seville Stephen A. Barney, W. J. Lewis, J. A. Beach and Oliver Berghof Index More information General index The following index includes only important terms and sub-topics, and most proper names, from the Etymologies. For larger topics consult the Analytical Table of Contents. Both English and Latin terms are indexed, but when a Latin term is close in meaning and form to the corresponding English translation, only the English is given. Book X is a dense list of such terms descriptive of human beings as “lifeless,” “hateful,” “generous,” “enviable.” Its Latin terms are in alphabetical order. Seeing that such terms are unlikely to be the object of an index search, and that including them would unduly swell the bulk of an index already large, we exclude Book X here, though not from the two indexes that follow. The valuable index of the Oroz Reta–Casquero Spanish translation of the Etymologies divides the terms into categories: a general index followed by indexes of proper names, geographical terms, botanical terms, zoological terms, and stones and minerals. Aaron 149, 164 acer 346 acyrology 56 abanet 383 acetum 398 Adam 162, 247, 302, 334, 384 abba 172 Achaea 290, 303 adamas 325 abbot 172 Achaeus 196, 290, 303 Adamite 175 abbreviations 51 Achaians 196 adiectio -

The Latin Past and the Poetry of Catullus

The Latin Past and the Poetry of Catullus by Jesse Michael Hill A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Classics University of Toronto © Copyright by Jesse Michael Hill, 2021 ii The Latin Past and the Poetry of Catullus Jesse Michael Hill Doctor of Philosophy Department of Classics University of Toronto 2021 Abstract This dissertation examines the relationship of the Latin poet Catullus to the preceding Latin poetic tradition, particularly to the pre-eminent figure of that tradition, pater Ennius. Classical scholarship has long thought the nature of this relationship settled: in a surge of revolutionary force (so goes the story), Catullus and his poetic peers (the “neoterics”) broke violently away from Ennius and the dominant Ennian tradition, turning instead to the recherché Greek poetry of the Hellenistic period for their inspiration. My study complicates this dominant narrative: Ennius, I argue, had a foundational, positive influence on Catullus; Catullan poetry was evolutionary, not revolutionary at Rome. Chapter 1 sets the stage by redefining neotericism: this was a broad poetic movement that included, not just Catullus and his friends (“the neoteric school”), but a majority of the Latin poets writing c. 90-40 BCE. Neotericism, moreover, was an evolutionary phenomenon, an elaboration of second-century Latin poetry. Chapters 2-4 attend to specific Catullan poems that engage closely and allusively with Ennius. Chapter 2 shows how, in poem 64, Catullus reinvents Roman epic on the model left to him by Ennius. Chapter 3 takes up poem 116, which I read as a programmatic statement of its author’s Ennian-Callimachean poetics. -

The Pen and the Sword: Writing and Conquest in Caesar's Gaul Author(S): Josiah Osgood Source: Classical Antiquity, Vol

The Pen and the Sword: Writing and Conquest in Caesar's Gaul Author(s): Josiah Osgood Source: Classical Antiquity, Vol. 28, No. 2 (October 2009), pp. 328-358 Published by: University of California Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/CA.2009.28.2.328 . Accessed: 07/08/2013 18:41 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. University of California Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Classical Antiquity. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 192.153.34.30 on Wed, 7 Aug 2013 18:41:57 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions JOSIAH OSGOOD The Pen and the Sword: Writing and Conquest in Caesar’s Gaul Julius Caesar was remembered in later times for the unprecedented scale of his military activity. He was also remembered for writing copiously while on campaign. Focusing on the period of Rome’s war with Gaul (58–50 bce), this paper argues that the two activities were interrelated: writing helped to facilitate the Roman conquest of the Gallic peoples. It allowed Caesar to send messages within his own theater of operations, sometimes with distinctive advantages; it helped him stay in touch with Rome, from where he obtained ever more resources; and it helped him, in his Gallic War above all, to turn the story of his scattered campaigns into a coherent narrative of the subjection of a vast territory henceforward to be called “Gaul.” The place of epistolography in late Republican politics receives new analysis in the paper, with detailed discussion of the evidence of Cicero. -

The Authority of Ennius and the Annales in Cicero's

THE AUTHORITY OF ENNIUS AND THE ANNALES IN CICERO’S PHILOSOPHICAL WORKS A Thesis Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Classics By Damien Provis Classics Department University of Canterbury August 2012 – May 2014 1 Contents Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................ 3 Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 4 CHAPTER 1: Authority .................................................................................................................. 11 What is a literary auctor? ............................................................................................................................ 13 Sources of authority in Cicero’s works .................................................................................................. 17 Conclusion ......................................................................................................................................................... 23 CHAPTER 2: Borrowed Authority: The importance of Cicero’s speakers .... 24 Direct involvement of the speaker: Cato and the De Senectute ................................................... 26 Attribution of quotations to figures from the poem: Pyrrhus and the De Officiis ................ 30 Conclusion ........................................................................................................................................................ -

2018 Harvard Certamen Advanced Division Round 1

2018 HARVARD CERTAMEN ADVANCED DIVISION ROUND 1 1. Listen carefully to the following passage from Cicero, which I will read twice, and answer the questions that follow in English: Et quoniam L. Torquātus, meus familiāris ac necessārius, iūdicēs, existimāvit, sī nostram in accūsātiōne suā necessitūdinem familiāritātemque violasset, aliquid sē dē auctōritāte meae dēfensiōnis posse dētrahere, cum huius perīculī prōpulsātiōne coniungam dēfensiōnem officī meī. The question: Whom is Cicero addressing here? THE JUDGES B1: What does Cicero consider Lucius Torquatus to be? HIS RELATIVE / KIN B2: What could Torquatus do to Cicero’s authority of his defense? DETRACT FROM IT 2. As a child, what son of Ctesius was lured by his Phoenician nurse to the ship of merchants and was sold as a slave to Laertes, for whom he then worked as a swineherd? EUMAEUS B1: What goatherd of Odysseus betrayed his master by bringing weapons to the suitors and was punished by being hung from the rafters? MELANTHIUS B2: Melanthius and his equally treacherous sister Melantho were the children of what loyal, old servant of Odysseus? DOLIUS 3. What derivative of a Latin noun meaning “threshold” means “denoting an action or event preceding or done in preparation for something fuller or more important” and describes the round which you are in? PRELIMINARY B1: What derivative of a Latin verb meaning “it is permitted” means “use of free time for enjoyment”? LEISURE B2: What derivative of a Latin verb meaning “to bind” means “a mass meeting of people making a political protest or showing support for a cause”? RALLY 4. -

A History of Roman Literature

A History of Roman Literature Charles Thomas Cruttwell A History of Roman Literature Table of Contents A History of Roman Literature...............................................................................................................................1 Charles Thomas Cruttwell.............................................................................................................................1 PREFACE......................................................................................................................................................2 INTRODUCTION.........................................................................................................................................9 BOOK I.....................................................................................................................................................................12 CHAPTER I. ON THE EARLIEST REMAINS OF THE LATIN LANGUAGE.......................................12 APPENDIX..................................................................................................................................................20 CHAPTER II. ON THE BEGINNINGS OF ROMAN LITERATURE......................................................21 CHAPTER III. THE INTRODUCTION OF GREEK LITERATURELIVIUS AND NAEVIUS (240−204 B.C.)...........................................................................................................................................27 CHAPTER IV. ROMAN COMEDYPLAUTUS TO TURPILIUS (254−103 B.C.).................................29 -

Marcus Terentius Varro

PEOPLE MENTIONED IN WALDEN PEOPLE MENTIONED IN A WEEK PEOPLE IN A WEEK AND IN WALDEN: 1 MARCUS TERENTIUS VARRO “NARRATIVE HISTORY” AMOUNTS TO FABULATION, THE REAL STUFF BEING MERE CHRONOLOGY 1. Sometimes referred to as Varro Reatinus to distinguish him from a younger contemporary, Varro Atacinus. HDT WHAT? INDEX PEOPLE OF A WEEK AND WALDEN:MARCUS TERENTIUS VARRO PEOPLE MENTIONED IN WALDEN WALDEN: Cato says that the profits of agriculture are particularly PEOPLE OF pious or just, (maximeque pius quæstus,) and according to Varro WALDEN the old Romans “called the same earth Mother and Ceres, and thought that they who cultivated it led a pious and useful life, and that they alone were left of the race of King Saturn.” CATO VARRO A WEEK: We sat awhile to rest us here upon the brink of the western PEOPLE OF bank, surrounded by the glossy leaves of the red variety of the A WEEK mountain laurel, just above the head of Wicasuck Island, where we could observe some scows which were loading with clay from the opposite shore, and also overlook the grounds of the farmer, of whom I have spoken, who once hospitably entertained us for a night. He had on his pleasant farm, besides an abundance of the beach-plum, or Prunus littoralis, which grew wild, the Canada plum under cultivation, fine Porter apples, some peaches, and large patches of musk and water melons, which he cultivated for the Lowell market. Elisha’s apple-tree, too, bore a native fruit, which was prized by the family. He raised the blood peach, which, as he showed us with satisfaction, was more like the oak in the color of its bark and in the setting of its branches, and was less liable to break down under the weight of the fruit, or the snow, than other varieties. -

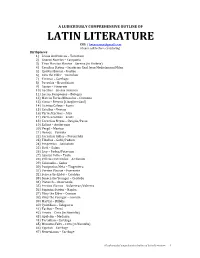

Ketan Ramakrishnan's Lit Notes, Expanded

A LUDICROUSLY COMPREHENSIVE OUTLINE OF LATIN LITERATURE KHR / [email protected] Please ask before circulating. Birthplaces 1) Livius Andronicus – Tarentum 2) Gnaeus Naevius – Campania 3) Titus Maccius Plautus – Sarsina (in Umbria) 4) Caecilius Statius – Insubrian Gaul from Mediolanum/Milan 5) Quintus Ennius – Rudiae 6) Cato the Elder – Tusculum 7) Terence – Carthage 8) Pacuvius – Brundisium 9) Accius – Pisaurum 10) Lucilius – Suessa Aurunca 11) Lucius Pomponius – Bologna 12) Marcus Furius Bibaculus – Cremona 13) Cinna – Brescia (Cisapline Gaul) 14) Licinius Calvus – Rome 15) Catullus – Verona 16) Varro Atacinus – Atax 17) Varro Reatinus – Reate 18) Cornelius Nepos – Ostiglia/Pavia 19) Sallust – Amiternum 20) Vergil – Mantua 21) Horace – Venusia 22) Cornelius Gallus – Forum Iulii 23) Tibullus – Gabii/Pedum 24) Propertius – Assissium 25) Ovid – Sulmo 26) Livy – Padua/Patavium 27) Asinius Pollo – Teate 28) Velleius Paterculus – Aeclanum 29) Columella – Gades 30) Pomponius Mela – Tingentera 31) Verrius Flaccus – Praeneste 32) Seneca the Elder – Cordoba 33) Seneca the Younger – Cordoba 34) Plutarch – Chaeroneia 35) Persius Flaccus – Volaterrae/Volterra 36) Papinius Statius – Naples 37) Pliny the Elder – Comum 38) Pliny the Younger – Comum 39) Martial – Bilbilis 40) Quintilian – Calagurris 41) Tacitus – Terni 42) Fronto – Cirta (in Numidia) 43) Apuleius – Madaura 44) Tertullian – Carthage 45) Minucius Felix – Cirta (in Numidia) 46) Cyprian – Carthage 47) Nemesianus – Carthage A Ludicrously Comprehensive Outline of Latin Literature 1 48) Arnobius