The Authority of Ennius and the Annales in Cicero's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Servius, Cato the Elder and Virgil

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by St Andrews Research Repository MEFRA – 129/1 – 2017, p. 85-100. Servius, Cato the Elder and Virgil Christopher SMITH C. Smith, British School at Rome, University of St Andrews, [email protected] This paper considers one of the most significant of the authors cited in the Servian tradition, Cato the Elder. He is cited more than any other historian, and looked at the other way round, Servius is a very important source for our knowledge of Cato. This paper addresses the questions of what we learn from Servius’ use of Cato, and what we learn about Virgil ? Servius, Cato the Elder, Virgil, Aeneas Cet article envisage la figure du principal auteur cite dans la tradition servienne, Caton l’Ancien. C’est l’historien le plus cité par Servius et, à l’inverse, Servius est une source très importante pour notre connaissance de Caton. Cet article revient sur l’utilisation de Caton par Servius et sur ce que Servius nous apprend sur Virgile. Servius, Catone l’Ancien, Virgile, Énée The depth of knowledge and understanding icance of his account of the beginnings of Rome. underpinning Virgil’s approach to Italy in the Our assumption that the historians focused on the Aeneid demonstrates that he was a profoundly earlier history and then passed rapidly over the learned poet ; and it was a learning which was early Republic is partly shaped by this tendency in clearly drawn on deep knowledge and under- the citing authorities2. -

The Supernatural in Tacitus When Compared with His Predecessor Livy, Tacitus Has Been Said to Be Less Interested in the “Super

The Supernatural in Tacitus When compared with his predecessor Livy, Tacitus has been said to be less interested in the “supernatural,” a rubric under which we include the prodigies and omens of traditional Roman religion; characters’ participation in forms of religious expression, both traditional and non-normative; and nebulous superhuman forces such as fate and fortune. In this panel, we seek to modify this perception by investigating aspects of the superhuman, religious, and/or inexplicable in Tacitus’ works that contribute in important ways to his historiographical project and to our view of Tacitus as an historian. As the most recent contribution on this topic shows (K. Shannon-Henderson, Religion and Memory in Tacitus’ Annals. Oxford, 2019), religion and its related fields are extremely important to Tacitus’ narrative technique, and ‘irrational’ elements such as fatum and fortuna are constantly at play in Tacitus’ works, particularly, but not exclusively, in his historical narratives. Each of the five papers that we have gathered for this panel addresses these topics from different angles, whether focusing more on the literary, historical, or linguistic elements of the Tacitean narrative under examination. Two papers focus on omens and other ways of predicting the future; two examine religious experiences of Tacitus’ characters; and one considers the role of fortuna in the world of the Dialogus. In the first paper, Contributor #1 examines the value of observing supernatural signs for decision-making in the Histories. In particular, s/he looks at the practical value of observing and interpreting supernatural signs as predictors of the future success or failure of military leaders. -

The Epic Vantage-Point: Roman Historiographical Allusion Reconsidered

Histos () – THE EPIC VANTAGE-POINT: ROMAN HISTORIOGRAPHICAL ALLUSION RECONSIDERED Abstract: This paper makes the case that Roman epic and Roman historiographical allusive practices are worth examining in light of each other, given the close relationship between the two genres and their common goal of offering their audiences access to the past. Ennius’ Annales will here serve as epic’s representative, despite its fragmentary state: the fact that the epic shares its subject-matter with and pre-dates most of the Roman historiographical tra- dition as we know it suggests that the poem may have had a significant role in setting the terms on which the two genres interacted at Rome; and what the first surviving generation of its readers, as principally represented by Cicero, have to say about the epic rather con- firms that suggestion (§I). Points of contact between the genres on which the paper focuses are: extended repetition of passages recognisable from previous authors (§II); allusion that is contested among the speakers of a given text (§III); citation practices (§IV); and the recur- rence of recognisable material stemming from the Annales in the historiographical tradition’s latter-day, when all sense of that material’s original context has been lost, along with its ability to generate new meaning (§V). n this paper,1 I consider how reading Ennius’ Annales can shed light on the extent to which allusion, as it operates in historiography, is differentiable I from allusion in other genres. David Levene has made the argument that historiography -

Faunus and the Fauns in Latin Literature of the Republic and Early Empire

University of Adelaide Discipline of Classics Faculty of Arts Faunus and the Fauns in Latin Literature of the Republic and Early Empire Tammy DI-Giusto BA (Hons), Grad Dip Ed, Grad Cert Ed Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy October 2015 Table of Contents Abstract ................................................................................................................... 4 Thesis Declaration ................................................................................................... 5 Acknowledgements ................................................................................................. 6 Introduction ............................................................................................................. 7 Context and introductory background ................................................................. 7 Significance ......................................................................................................... 8 Theoretical framework and methods ................................................................... 9 Research questions ............................................................................................. 11 Aims ................................................................................................................... 11 Literature review ................................................................................................ 11 Outline of chapters ............................................................................................ -

TRADITIONAL POETRY and the ANNALES of QUINTUS ENNIUS John Francis Fisher A

REINVENTING EPIC: TRADITIONAL POETRY AND THE ANNALES OF QUINTUS ENNIUS John Francis Fisher A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE FACULTY OF PRINCETON UNIVERSITY IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY RECOMMENDED FOR ACCEPTANCE BY THE DEPARTMENT OF CLASSICS SEPTEMBER 2006 UMI Number: 3223832 UMI Microform 3223832 Copyright 2006 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346 © Copyright by John Francis Fisher, 2006. All rights reserved. ii Reinventing Epic: Traditional Poetry and the Annales of Quintus Ennius John Francis Fisher Abstract The present scholarship views the Annales of Quintus Ennius as a hybrid of the Latin Saturnian and Greek hexameter traditions. This configuration overlooks the influence of a larger and older tradition of Italic verbal art which manifests itself in documents such as the prayers preserved in Cato’s De agricultura in Latin, the Iguvine Tables in Umbrian, and documents in other Italic languages including Oscan and South Picene. These documents are marked by three salient features: alliterative doubling figures, figurae etymologicae, and a pool of traditional phraseology which may be traced back to Proto-Italic, the reconstructed ancestor of the Italic languages. A close examination of the fragments of the Annales reveals that all three of these markers of Italic verbal art are integral parts of the diction the poem. Ennius famously remarked that he possessed three hearts, one Latin, one Greek and one Oscan, which the second century writer Aulus Gellius understands as ability to speak three languages. -

Jacqueline Michelle Elliott Department of Classics University of Colorado, 248 UCB Boulder, CO 80309-0248; 303-492-7944; [email protected]

Jacqueline Michelle Elliott Department of Classics University of Colorado, 248 UCB Boulder, CO 80309-0248; 303-492-7944; [email protected] Education: 2005 PhD (Classics), Columbia University 2002 MPhil (Classics), Columbia University 2000 MA (Greek), Columbia University 1995 BA (Classics), University College, Oxford Dissertation (Columbia University): History and Poetry in Ennius’ Annales (Sponsor: J.E.G. Zetzel) Academic employment: University of Colorado at Boulder: 2013– Associate Professor of Classics 2005–13 Assistant Professor of Classics Columbia University: 2002–4 Core Curriculum (Literature Humanities) Preceptor 1999–2002 Classics Department Teaching Fellow Marlboro College, Vermont: 1995–7 Classics Teaching Fellow Teaching and research interests: • The epic tradition from Homer to Vergil • Roman Republican historiography • The theory and practice of commentaries • Intertextuality and reception Book: • Ennius and the Architecture of the Annales (Cambridge 2013): http://www.cambridge.org/gb/knowledge/isbn/item6953544/Ennius%20and%20the%20Architect ure%20of%20the%20%3CEM%3EAnnales%3C/EM%3E/?site_locale=en_GB o Eugene M. Kayden Book Award 2014. o CAMWS First Book Award 2015. o Rev. W. Fitzgerald, Times Literary Supplement 4 June 2014, ‘O Tite, tute’; J. Nethercut, Classical Journal Online 2014.10.04 (http://cj.camws.org/sites/default/files/reviews/2014.10.04%20Nethercut%20on%20Elliott.pd f); Gesine Manuwald, Gymnasium 121 (6), 2014, 608-10; J.H. Clark, Histos 9 (2015), I-VIII: http://research.ncl.ac.uk/histos/documents/2015RD01ClarkonElliottEnnius.pdf; Nora Goldschmidt, Journal of Roman Studies (2015): http://journals.cambridge.org/action/displayAbstract?fromPage=online&aid=9694532&fileId =S0075435815000556. Journal articles: • ‘Ennius’ ‘Cunctator’ and the history of a gerund in the Roman historiographical tradition’, Classical Quarterly 59.2, 2009, 531–41. -

Tacitus on Marcus Lepidus, Thrasea Paetus, and Political Action Under the Principate Thomas E

Xavier University Exhibit Faculty Scholarship Classics 2010 Saving the Life of a Foolish Poet: Tacitus on Marcus Lepidus, Thrasea Paetus, and Political Action under the Principate Thomas E. Strunk Xavier University - Cincinnati Follow this and additional works at: http://www.exhibit.xavier.edu/classics_faculty Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, Ancient Philosophy Commons, Byzantine and Modern Greek Commons, Classical Archaeology and Art History Commons, Classical Literature and Philology Commons, Indo-European Linguistics and Philology Commons, and the Other Classics Commons Recommended Citation Strunk, Thomas E., "Saving the Life of a Foolish Poet: Tacitus on Marcus Lepidus, Thrasea Paetus, and Political Action under the Principate" (2010). Faculty Scholarship. Paper 15. http://www.exhibit.xavier.edu/classics_faculty/15 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Classics at Exhibit. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Exhibit. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SYLLECTA CLASSICA 21 (2010): 119–139 SAVING THE LIFE OF A FOOLISH POET: TACITUS ON MARCUS LEPIDUS, THRASEA PAETUS, AND POLITICAL ACTION UNDER THE PRINCIPATE Thomas E. Strunk Abstract: This paper explores Tacitus’ representation of Thrasea Paetus. Preliminary to analyzing this portrayal, I discuss two pas- sages often cited when exploring Tacitus’ political thought, Agricola 42.4 and Annales 4.20. I reject the former’s validity with regard to Thrasea and accept the latter as a starting point for comparing Tacitus’ depictions of Marcus Lepidus and Thrasea. Tacitus’ char- acterizations of Thrasea and Lepidus share the greatest resemblance in the trials of Antistius Sosianus and Clutorius Priscus, both of whom wrote verses offensive to the regime. -

The Maltese Islands and the Sea in Antiquity

THE MALTESE ISLANDS AND THE SEA IN ANTIQUITY The Maltese Islands and the Sea in Antiquity TIMMY GAMBIN The events of history often lead to the islands… F. Braudel THE STRETCHES OF SEA EXTANT BETWEEN ISLANDS AND mainland may be observed as having primary-dual functionalities: that of ‘isolating’ islands and that of providing connectivity with land masses that lay beyond the islands’ shores. On smaller islands especially, access to the sea provided a gateway from which people, goods and ideas could flow. This chapter explores how, via their surrounding seas, events of history often led to the islands of Malta and Gozo. The timeframe covered consists of over one thousand years (circa 700 BC to circa 400 AD); a fluid period that saw the island move in and out of the political, military and economic orbits of various powers that dominated the Mediterranean during these centuries. Another notion of duality can be observed in the interaction that plays out between those coming from the outside and those inhabiting the islands. It would be mistaken to analyze Maltese history solely in the context of great powers that touched upon and ‘colonized’ the islands. This historical narrative will also cover important aspects such as how the islands were perceived from those approaching from out at sea: were the islands a hazard, a haven or possibly both at one and the same time? It is also essential to look at how the sea was perceived by the islanders: did the sea bring welcome commercial activity to the islands shores; did it carry 1 THE MALTESE ISLANDS AND THE SEA pirate vessels and enemy ships? As important as these questions are, this narrative would be incomplete without reference to how the sea helped shape and mould the way in which the people living on Malta and Gozo chose (or were forced) to live. -

Introduction: Medea in Greece and Rome

INTRODUCTION: MEDEA IN GREECE AND ROME A J. Boyle maiusque mari Medea malum. Seneca Medea 362 And Medea, evil greater than the sea. Few mythic narratives of the ancient world are more famous than the story of the Colchian princess/sorceress who betrayed her father and family for love of a foreign adventurer and who, when abandoned for another woman, killed in revenge both her rival and her children. Many critics have observed the com plexities and contradictions of the Medea figure—naive princess, knowing witch, faithless and devoted daughter, frightened exile, marginalised alien, dis placed traitor to family and state, helper-màiden, abandoned wife, vengeful lover, caring and filicidal mother, loving and fratricidal sister, oriental 'other', barbarian saviour of Greece, rejuvenator of the bodies of animals and men, killer of kings and princesses, destroyer and restorer of kingdoms, poisonous stepmother, paradigm of beauty and horror, demi-goddess, subhuman monster, priestess of Hecate and granddaughter of the sun, bride of dead Achilles and ancestor of the Medes, rider of a serpent-drawn chariot in the sky—complex ities reflected in her story's fragmented and fragmenting history. That history has been much examined, but, though there are distinguished recent exceptions, comparatively little attention has been devoted to the specifically 'Roman' Medea—the Medea of the Republican tragedians, of Cicero, Varro Atacinus, Ovid, the younger Seneca, Valerius Flaccus, Hosidius Geta and Dracontius, and, beyond the literary field, the Medea of Roman painting and Roman sculp ture. Hence the present volume of Ramus, which aims to draw attention to the complex and fascinating use and abuse of this transcultural heroine in the Ro man intellectual and visual world. -

Latin Literature

Latin Literature By J. W. Mackail Latin Literature I. THE REPUBLIC. I. ORIGINS OF LATIN LITERATURE: EARLY EPIC AND TRAGEDY. To the Romans themselves, as they looked back two hundred years later, the beginnings of a real literature seemed definitely fixed in the generation which passed between the first and second Punic Wars. The peace of B.C. 241 closed an epoch throughout which the Roman Republic had been fighting for an assured place in the group of powers which controlled the Mediterranean world. This was now gained; and the pressure of Carthage once removed, Rome was left free to follow the natural expansion of her colonies and her commerce. Wealth and peace are comparative terms; it was in such wealth and peace as the cessation of the long and exhausting war with Carthage brought, that a leisured class began to form itself at Rome, which not only could take a certain interest in Greek literature, but felt in an indistinct way that it was their duty, as representing one of the great civilised powers, to have a substantial national culture of their own. That this new Latin literature must be based on that of Greece, went without saying; it was almost equally inevitable that its earliest forms should be in the shape of translations from that body of Greek poetry, epic and dramatic, which had for long established itself through all the Greek- speaking world as a common basis of culture. Latin literature, though artificial in a fuller sense than that of some other nations, did not escape the general law of all literatures, that they must begin by verse before they can go on to prose. -

Latin Literature 1

Latin Literature 1 Latin Literature The Project Gutenberg EBook of Latin Literature, by J. W. Mackail Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this or any other Project Gutenberg eBook. This header should be the first thing seen when viewing this Project Gutenberg file. Please do not remove it. Do not change or edit the header without written permission. Please read the "legal small print," and other information about the eBook and Project Gutenberg at the bottom of this file. Included is important information about your specific rights and restrictions in how the file may be used. You can also find out about how to make a donation to Project Gutenberg, and how to get involved. **Welcome To The World of Free Plain Vanilla Electronic Texts** **eBooks Readable By Both Humans and By Computers, Since 1971** *****These eBooks Were Prepared By Thousands of Volunteers!***** Title: Latin Literature Author: J. W. Mackail Release Date: September, 2005 [EBook #8894] [Yes, we are more than one year ahead of schedule] [This file was first posted on August 21, 2003] Edition: 10 Latin Literature 2 Language: English Character set encoding: ISO−8859−1 *** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK LATIN LITERATURE *** Produced by Distributed Proofreaders LATIN LITERATURE BY J. W. MACKAIL, Sometime Fellow of Balliol College, Oxford A history of Latin Literature was to have been written for this series of Manuals by the late Professor William Sellar. After his death I was asked, as one of his old pupils, to carry out the work which he had undertaken; and this book is now offered as a last tribute to the memory of my dear friend and master. -

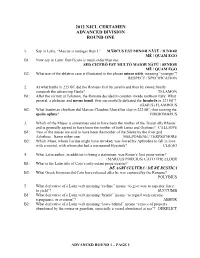

2012 Njcl Certamen Advanced Division Round One

2012 NJCL CERTAMEN ADVANCED DIVISION ROUND ONE 1. Say in Latin, “Marcus is younger than I.” MĀRCUS EST MINOR NĀTŪ / IUNIOR MĒ / QUAM EGO B1: Now say in Latin: But Cicero is much older than me. SED CICERŌ EST MULTŌ MAIOR NĀTŪ / SENIOR MĒ / QUAM EGO B2: What use of the ablative case is illustrated in the phrase minor nātū, meaning “younger”? RESPECT / SPECIFICATION 2. At what battle in 225 BC did the Romans first by javelin and then by sword finally vanquish the advancing Gauls? TELAMON B1: After the victory at Telamon, the Romans decided to counter-invade northern Italy. What general, a plebeian and novus homō, first successfully defeated the Insubrēs in 223 BC? (GAIUS) FLAMINIUS B2: What Insubrian chieftain did Marcus Claudius Marcellus slay in 222 BC, thus earning the spolia opīma? VIRIDOMARUS 3. Which of the Muses is sometimes said to have been the mother of the Trojan ally Rhesus and is generally agreed to have been the mother of both Linus and Orpheus? CALLIOPE B1: Two of the muses are said to have been the mother of the Sirens by the river god Achelous. Name either one. MELPOMENE / TERPSICHORE B2: Which Muse, whom Tacitus might have invoked, was forced by Aphrodite to fall in love with a mortal, with whom she had a son named Hyacinth? CL(E)IO 4. What Latin author, in addition to being a statesman, was Rome’s first prose writer? (MARCUS PORCIUS) CATO THE ELDER B1: What is the Latin title of Cato’s only extant prose treatise? DĒ AGRĪ CULTŪRĀ / DĒ RĒ RUSTICĀ B2: What Greek historian did Cato have released after he was captured by the Romans? POLYBIUS 5.