World Englishes in Asian Contexts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Twenty-Third International Congress of Vedanta August 10-13, 2017

Twenty - Third International Congress of Vedanta August 10 - 13, 2017 On August 10 - 13, 2017 the Twenty - Third International Congress of Vedanta was hosted by T he Center for Indic Studies, University of Massachusetts, Dartmouth, USA in collaboration with the Institute of Advanced Sciences, Dartmouth, USA . The inauguration session started in the morning of first day with Vedic c hanting performed by Swami Yogatmananda, Vedanta Society of Providence, and Swami Atmajnanananda, Vedanta Center of Greater Washington , DC . Welcome address and i ntroduction presented by Conference Director Prof. Sukalyan Sengupta, University of Massachusetts , Dartmouth. Founding Director, Vedanta Congress Prof. S.S. Ramarao Pappu was felicitated in this session. Conference started with an inaugural l ecture by Mr. Rajeev Srinivasan on “ Leveraging the Grand Dharmic Narrative for Soft Power ”. Dr. Alex Hankey, SVYASA Bangalore and Dr. Makarand Paranjape, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New D elhi were the keynote speakers during this inaugural session . They deliver ed their talk s on “ Synthesizing Vedic and Modern Theories to Explain Cognition of Forms ” and “ Vedanta and Aesthetics ” , respectively. This session was concluded under the chairmanship of Prof. Raghwendra P . Singh, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, India. Inaugural Session, 23 rd International Vedanta Congress The Vedanta Congress continues its tradition of bringing scholars of Indic traditions from India and the West together on a platform nearly from three decades. Delegates from various -

The Maintenance of Malaysia's Minority Languages Haja

THE MAINTENANCE OF MALAYSIA’S MINORITY LANGUAGES HAJA MOHIDEEN BIN MOHAMED ALI Department of English Language & Literature International Islamic University Malaysia [email protected] Abstract Malaysia, especially the states of Sabah and Sarawak are home to numerous indigenous languages. According to the Ethnologue Report for Malaysia (2009), Sabah is said to have 52 and Sarawak 46 languages. But among these many languages, many are spoken by a small population. These are in danger of facing extinction due to migration, attitudinal, social, educational and economic factors, mainly. This situation is similar to the many languages which are dying today worldwide. Since the Malay language (Bahasa Malaysia) is a potent force in bringing together the various Bumiputra and Muslim groups, the fate of native languages of these disparate groups is uncertain or worse doomed to die. However, measures by speakers of indigenous languages who comprise a sizeable number, for example, in the case of Sabah, Kadazan, Bajau, Bisaya and Murut languages may still be saved if they are maintained through concerted efforts by the affected communities and if government agencies help to play their part. This paper will discuss the various practical steps that may be undertaken by concerned individuals, the elders and leaders of the target minority communities themselves, language scholars and the state and federal governments to help maintain the minority indigenous languages, with particular emphasis on those from Sabah and Sarawak. Key words- minority language, identity, linguistic diversity, survival, loss Introduction Multilingualism and multiculturalism are indeed assets for a country and its people. The two contribute to the versatility and heterogeneity of a country‟s human landscape. -

A Dictionary of Kristang (Malacca Creole Portuguese) with an English-Kristang Finderlist

A dictionary of Kristang (Malacca Creole Portuguese) with an English-Kristang finderlist PacificLinguistics REFERENCE COpy Not to be removed Baxter, A.N. and De Silva, P. A dictionary of Kristang (Malacca Creole Portuguese) English. PL-564, xxii + 151 pages. Pacific Linguistics, The Australian National University, 2005. DOI:10.15144/PL-564.cover ©2005 Pacific Linguistics and/or the author(s). Online edition licensed 2015 CC BY-SA 4.0, with permission of PL. A sealang.net/CRCL initiative. Pacific Linguistics 564 Pacific Linguistics is a publisher specialising in grammars and linguistic descriptions, dictionaries and other materials on languages of the Pacific, Taiwan, the Philippines, Indonesia, East Timor, southeast and south Asia, and Australia. Pacific Linguistics, established in 1963 through an initial grant from the Hunter Douglas Fund, is associated with the Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies at The Australian National University. The authors and editors of Pacific Linguistics publications are drawn from a wide range of institutions around the world. Publications are refereed by scholars with relevant expertise, who are usually not members of the editorial board. FOUNDING EDITOR: Stephen A. Wurm EDITORIAL BOARD: John Bowden, Malcolm Ross and Darrell Tryon (Managing Editors), I Wayan Arka, Bethwyn Evans, David Nash, Andrew Pawley, Paul Sidwell, Jane Simpson EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD: Karen Adams, Arizona State University Lillian Huang, National Taiwan Normal Peter Austin, School of Oriental and African University Studies -

Learn Thai Language in Malaysia

Learn thai language in malaysia Continue Learning in Japan - Shinjuku Japan Language Research Institute in Japan Briefing Workshop is back. This time we are with Shinjuku of the Japanese Language Institute (SNG) to give a briefing for our students, on learning Japanese in Japan.You will not only learn the language, but you will ... Or nearby, the Thailand- Malaysia border. Almost one million Thai Muslims live in this subregion, which is a belief, and learn how, to grow other (besides rice) crops for which there is a good market; Thai, this term literally means visitor, ASEAN identity, are we there yet? Poll by Thai Tertiary Students ' Sociolinguistic. Views on the ASEAN community. Nussara Waddsorn. The Assumption University usually introduces and offers as a mandatory optional or free optional foreign language course in the state-higher Japanese, German, Spanish and Thai languages of Malaysia. In what part students find it easy or difficult to learn, taking Mandarin READING HABITS AND ATTITUDES OF THAI L2 STUDENTS from MICHAEL JOHN STRAUSS, presented partly to meet the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS (TESOL) I was able to learn Thai with Sukothai, where you can learn a lot about the deep history of Thailand and culture. Be sure to read the guide and learn a little about the story before you go. Also consider visiting neighboring countries like Cambodia, Vietnam and Malaysia. Air LANGUAGE: Thai, English, Bangkok TYPE OF GOVERNMENT: Constitutional Monarchy CURRENCY: Bath (THB) TIME ZONE: GMT No 7 Thailand invites you to escape into a world of exotic enchantment and excitement, from the Malaysian peninsula. -

Debashish Banerji Makarand R. Paranjape Editors Critical Posthumanism and Planetary Futures Critical Posthumanism and Planetary Futures Debashish Banerji • Makarand R

Debashish Banerji Makarand R. Paranjape Editors Critical Posthumanism and Planetary Futures Critical Posthumanism and Planetary Futures Debashish Banerji • Makarand R. Paranjape Editors Critical Posthumanism and Planetary Futures 123 Editors Debashish Banerji Makarand R. Paranjape California Institute of Integral Studies Jawaharlal Nehru University San Francisco, CA New Delhi USA India ISBN 978-81-322-3635-1 ISBN 978-81-322-3637-5 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-81-322-3637-5 Library of Congress Control Number: 2016947189 © Springer India 2016 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. Printed on acid-free paper This Springer imprint is published by Springer Nature The registered company is Springer (India) Pvt. -

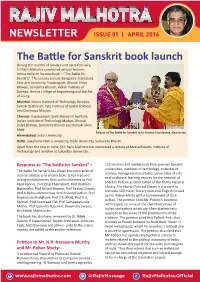

The Battle for Sanskrit Book Launch

NEWSLETTER ISSUE 01 | APRIL 2016 The Battle for Sanskrit book launch During the months of January and early February, Sri Rajiv Malhotra conducted various lectures across India on his new book – “The Battle for Sanskrit”. The venues include Bangalore: Karnataka Samskrit University, Yuvabrigade, Bharati Vidya Bhavan, Samskrita Bharati, Indian Institute of Science, Amrita College of Engineering and the Art of Living. Mumbai: Indian Institute of Technology Bombay, Samskrita Bharati, Tata Institute of Social Sciences and Chinmaya Mission. Chennai: Kuppuswami Sastri Research Institute, Indian Institute of Technology Madras, Bharati Vidya Bhavan, Samskrita Bharati and Ramakrishna Mutt. Release of The Battle for Sanskrit at Sri Krishna Vrundavana, New Jersey Ahmedabad: Indus University. Delhi: Jawaharlal Nehru University, Delhi University, Samskrita Bharati. Apart from the tour in India, Shri Rajiv Malhotra has conducted a lecture at Massachusetts Institute of Technology and another at Columbia University. Response to “The Battle for Sanskrit”:- 132 scholars and intellectuals from premier Sanskrit universities, institutes of technology, institutes of The Battle for Sanskrit has drawn the admiration of science, management institutes, universities of arts several scholars and intellectuals. It has received and traditional learning centres for the removal of strong endorsements from such luminaries as Prof Sheldon Pollock as Chief Editor of the Murty Classical Kapil Kapoor, Prof Dilip Chakrabarti, Prof Roddam Library. The Murty Classical Library is a project to Narasimha, Prof Arvind Sharma, Prof Pankaj Chande, translate 500 Indian literary texts into English funded Prof K Ramasubramanian, Prof R Vaidyanathan, Prof by Mr. Rohan Murty with a commitment of $5.6 Dayananda Bharghava, Prof S.R. Bhatt, Prof K.S. -

The Case for Sanskrit As India's National Language by Makarand

The Case for Sanskrit as India’s National Language By Makarand Paranjape August 2012 This paper discusses in depth the role and the potential of Sanskrit in India’s cultural and national landscape. Reproduced with the author’s permission, it has been published in Sanskrit and Other Indian Languages , ed. Shashiprabha Kumar (New Delhi: D. K. Printworld, 2007), pp. 173- 200. “Sanskrit is the thread on which the pearls of the necklace of Indian culture are strung; break the thread and all the pearls will be scattered, even lost forever.” Dr. Lokesh Chandra Introduction I had first heard from my friends in the Sri Aurobindo Ashram, Pondicherry, that the Mother wanted Sanskrit to be made the national language of India. Indeed, Sanskrit is taught from childhood not only in the ashram schools, but also at Auroville, the comm unity that the Mother founded. On 11th November 1967, the Mother said: “ Sanskrit! Everyone should learn that. Especially everyone who works here should learn that….” 1 Because some degree of confusion persisted over the Mother’s and Sri Aurobindo’s views on the topic, a more direct question was put to the former on 4 October 1971: On certain issues where You and Sri Aurobindo have given direct answers, we [Sri Aurobindo's Action] are also specific, as for instance... on the language issue where You have said for the country that (1) the regional language should be the medium of instruction, (2) Sanskrit should be the national language, and (3) English should be the international language. Are we correct in giving these replies to such questions? Yes. -

Strength for Today and Bright Hope for Tomorrow Volume 8: 7 July 2008

LANGUAGE IN INDIA Strength for Today and Bright Hope for Tomorrow Volume 8 : 7 July 2008 ISSN 1930-2940 Managing Editor: M. S. Thirumalai, Ph.D. Editors: B. Mallikarjun, Ph.D. Sam Mohanlal, Ph.D. B. A. Sharada, Ph.D. A. R. Fatihi, Ph.D. Lakhan Gusain, Ph.D. K. Karunakaran, Ph.D. Jennifer Marie Bayer, Ph.D. Survival of the Minority Kristang Language in Malaysia Haji Mohideen Bin Mohamed Ali, Ph.D. Shamimah Mohideen, M. HSc. 1 Survival of the Minority Kristang Language in Malaysia Haja Mohideen Bin Mohamed Ali, Ph.D. Shamimah Mohideen, M.HSc. Abstract Kristang, also known as the Malaccan Portuguese Creole, has a strong influence of Portuguese, together with the Malay language which is the dominant local language in Malaysia and the Malay-speaking region in Southeast Asia. This Creole is spoken by a microscopic minority of Catholic Christians who are descendants of Portuguese colonizers and Asian settlers in Malacca. Malacca was once a historically renowned state and empire which was coveted by major European powers. The Dutch followed the Portuguese and the last were the British. Because of the very small number of Kristang community members (1200) in the present Portuguese Settlement assigned to them by the authorities, the Kristang language is clearly a language struggling to survive. Its vocabulary is largely Portuguese-based, with a substantial contribution from the Malay language. It has also borrowed from the languages of other colonial European powers. Their vocabulary also includes some loan words from Chinese and Indian languages. This minority language may yet be maintained with the fervent effort of the few thousand remaining Kristang speakers and the Malaysian government, particularly the state government of Melaka (or Malacca). -

Kodrah Kristang: the Initiative to Revitalize the Kristang Language in Singapore

Language Documentation & Conservation Special Publication No. 19 Documentation and Maintenance of Contact Languages from South Asia to East Asia ed. by Mário Pinharanda-Nunes & Hugo C. Cardoso, pp.35–121 http:/nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc/sp19 2 http://hdl.handle.net/10125/24906 Kodrah Kristang: The initiative to revitalize the Kristang language in Singapore Kevin Martens Wong National University of Singapore Abstract Kristang is the critically endangered heritage language of the Portuguese-Eurasian community in Singapore and the wider Malayan region, and is spoken by an estimated less than 100 fluent speakers in Singapore. In Singapore, especially, up to 2015, there was almost no known documentation of Kristang, and a declining awareness of its existence, even among the Portuguese-Eurasian community. However, efforts to revitalize Kristang in Singapore under the auspices of the community-based non-profit, multiracial and intergenerational Kodrah Kristang (‘Awaken, Kristang’) initiative since March 2016 appear to have successfully reinvigorated community and public interest in the language; more than 400 individuals, including heritage speakers, children and many people outside the Portuguese-Eurasian community, have joined ongoing free Kodrah Kristang classes, while another 1,400 participated in the inaugural Kristang Language Festival in May 2017, including Singapore’s Deputy Prime Minister and the Portuguese Ambassador to Singapore. Unique features of the initiative include the initiative and its associated Portuguese-Eurasian community being situated in the highly urbanized setting of Singapore, a relatively low reliance on financial support, visible, if cautious positive interest from the Singapore state, a multiracial orientation and set of aims that embrace and move beyond the language’s original community of mainly Portuguese-Eurasian speakers, and, by design, a multiracial youth-led core team. -

Professor Makarand Paranjape Currently Holds the ICCR Chair in Indian Studies, South Asian Studies Programme, National University of Singapore

The Center for the Study of Hindu Traditions, University of Florida presents The Relevance of Gandhi to Environmental Studies by Professor Makarand Paranjape Professor Makarand Paranjape currently holds the ICCR Chair in Indian Studies, South Asian Studies Programme, National University of Singapore. He is also Professor of English, Centre for English Studies, School of Language, Literature, and Culture Studies at the Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. He received his M.A. and Ph.D. in English from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Professor Paranjape has held a number of fellowships in several universities; he was previously the Homi Bhabha Fellow for Literature in India; Shastri Indo-Candian Research Fellow, University of Calgary; IFUSS Fellow, University of Iowa; Mellon Fellow, Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, University of Texas at Austin; and Shivdasani Visiting Fellow, Oxford Centre for Hindu Studies, University of Oxford. He has also been a Visiting Professor at the Universitat Autonoma de Barcelona and the Universitat des Sarlandes. Professor Paranjape will also be leading a class discussion on Hindu Traditions in Singapore (April 11, 2:30 pm, Room 117, Anderson Hall) Professor Paranjape is the author or editor of several books including Decolonization and Development: Hind Svaraj Revisioned (1993); Nativism: Essays in Literary Criticism (Sahitya Akademi, 1997); In Diaspora: Theories, Histories, Texts, Editor (2001); Sacred Australia: post-secular considerations (2009); Altered Destinations: Self, Society, and Nation in India (Perth: University of Western Australia Press, 2010); Bollywood in Australia: Transnationalism and Cultural Production (Perth: University of Western Australia Press, 2010); as well as the author of several volumes of poetry and fiction.. -

A Group of Enthusiasts Are Speaking up for Kristang, One of the Heritage Languages of the Eurasian Community in Singapore and Malaysia

www.eurasians.org.sg JULY - SEPTEMBER 2017 PLUS MAKE EURASIAN HISTORY! The National Archives needs volunteers KRISTANG GETS COOL Our heritage language has its very own celebration SAVING LIVES EVERY DAY Melody Bellido, peri-operative staff nurse MCI (P) 047/04/2017 PATRONS Herman Hochstadt CONTENTS George Yeo TRUSTEES Barry Desker Timothy de Souza Gerald Minjoot Gerard de Silva Judith Prakash Edward D’Silva AUDIT COMMITTEE Boris Link Helen Lee Lim Yih Chyi LEGAL ADVISORY PANEL 09 Carla Barker (Chair) William da Silva AT THE HELM MANAGEMENT COMMITTEE President 03 President’s message Benett Theseira 1st Vice President Alexius Pereira 2nd Vice President NEWS Yvonne Pereira 09 Honorary Secretary 04 A visit from the President of Singapore Angelina Fernandez Honorary Treasurer Making closer ties with Portugal Martin Marini YOUTH EA-inspired book wins top title Committee Members Graham Ong-Webb Think differently – and ace your exams! 05 EA Toastmasters are far from shy and 15 Julia D’Silva retiring 16 Danni Jay has plans to inspire young Christopher Gordon Vincent Schoon Lady Luck smiles on a new baluteer Eurasians SECRETARIAT Get involved in saving our history! 06 General Manager A special present for a loyal Eurasian Lester Low Senior Accountant CULTURE AND HERITAGE Bernadette Soh 17 Teaching the teachers about our Manager (Heritage & Culture) EDUCATION heritage Jacqueline Peeris Manager (Corporate Communications) 07 Youngsters learn the secrets of A Eurasian tour M Revathhi coding Assistant Manager (Casework, FSS) 18 Getting creative with -

A Chan, a Tancareira

INDEX “A Chan, a Tancareira” (Senna Albuquerque, Pedro António de Fernandes), 250 Meneses Noronha de, 73 Abriz, José, 38 Ali, Ha¯jı¯ Muha¯mmad, 73 Abu’l Hasan (sultan), 71 Allen, Charles Herbert, 179 Aceh Almeida, António José de Miranda e, Portuguese conflicts with, 51, 53, 36 57 Almeida, Manuel de, 122 sultan and sultanate of, 50 Almeida, Miguel Vale de, 72–73, 242, adaptation, 4–5, 6, 10, 19, 240, 255 259 Afonso, Inácio Caetano, 35, 37 An Earth-Colored Sea, 259 Africa, 12, 26, 29, 140, 173 Almeida, Teresa da Piedade de Baptista Lusophone, 131, 143, 242, 271 See Devi, Vimala (pseud.) plants from, 33, 34, 39 aloe, 40 Africans, 11, 12, 133, 135, 138, 160, althea, 40 170, 245, 249 Álvares, Gaspar Afonso, 69 See also slaves Amaral, Miguel de, 90 Agualusa, José Eduardo, 261, 265, 270 American Institute of Indian Studies, Um Estranho em Goa, 261–63, 270 xi Fronteiras Perdidas, 265 Ames, Glenn Joseph, xi–xiii “A Nossa Pátria na Malásia”, 270 works by, xiii Aguiar, António de, 86, 89, 97 Amor e Dedinhos de Pé (Senna “Ah Chan, the Tanka Girl” (Senna Fernandes), 247, 250–54 Fernandes) Amorim, Francisco Gomes de, 183 See “A Chan, a Tancareira” An Earth-Colored Sea (Almeida), 259 air forces Anderson, Benedict, 236, 240–41, 255 Royal Air Force, 217 See also imagined communities United States Army Air Forces, Anglo-Asians, 132 Fourteenth Air Force, 215 See also Luso-Asians Ajuda Palace, 36 Anglo-Indians, 134, 139 Albuquerque, Afonso de, 48, 54 and White Australia policy, 143 299 14 Portuguese_1.indd 299 10/31/11 10:17:12 AM 300 Index Anglo-Portuguese