THE TOUCH of SAKTI.Cdr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notes and Topics: Synopsis of Taranatha's History

SYNOPSIS OF TARANATHA'S HISTORY Synopsis of chapters I - XIII was published in Vol. V, NO.3. Diacritical marks are not used; a standard transcription is followed. MRT CHAPTER XIV Events of the time of Brahmana Rahula King Chandrapala was the ruler of Aparantaka. He gave offerings to the Chaityas and the Sangha. A friend of the king, Indradhruva wrote the Aindra-vyakarana. During the reign of Chandrapala, Acharya Brahmana Rahulabhadra came to Nalanda. He took ordination from Venerable Krishna and stu died the Sravakapitaka. Some state that he was ordained by Rahula prabha and that Krishna was his teacher. He learnt the Sutras and the Tantras of Mahayana and preached the Madhyamika doctrines. There were at that time eight Madhyamika teachers, viz., Bhadantas Rahula garbha, Ghanasa and others. The Tantras were divided into three sections, Kriya (rites and rituals), Charya (practices) and Yoga (medi tation). The Tantric texts were Guhyasamaja, Buddhasamayayoga and Mayajala. Bhadanta Srilabha of Kashmir was a Hinayaist and propagated the Sautrantika doctrines. At this time appeared in Saketa Bhikshu Maha virya and in Varanasi Vaibhashika Mahabhadanta Buddhadeva. There were four other Bhandanta Dharmatrata, Ghoshaka, Vasumitra and Bu dhadeva. This Dharmatrata should not be confused with the author of Udanavarga, Dharmatrata; similarly this Vasumitra with two other Vasumitras, one being thr author of the Sastra-prakarana and the other of the Samayabhedoparachanachakra. [Translated into English by J. Masuda in Asia Major 1] In the eastern countries Odivisa and Bengal appeared Mantrayana along with many Vidyadharas. One of them was Sri Saraha or Mahabrahmana Rahula Brahmachari. At that time were composed the Mahayana Sutras except the Satasahasrika Prajnaparamita. -

Abhinavagupta's Portrait of a Guru: Revelation and Religious Authority in Kashmir

Abhinavagupta's Portrait of a Guru: Revelation and Religious Authority in Kashmir The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:39987948 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Abhinavagupta’s Portrait of a Guru: Revelation and Religious Authority in Kashmir A dissertation presented by Benjamin Luke Williams to The Department of South Asian Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of South Asian Studies Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts August 2017 © 2017 Benjamin Luke Williams All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Parimal G. Patil Benjamin Luke Williams ABHINAVAGUPTA’S PORTRAIT OF GURU: REVELATION AND RELIGIOUS AUTHORITY IN KASHMIR ABSTRACT This dissertation aims to recover a model of religious authority that placed great importance upon individual gurus who were seen to be indispensable to the process of revelation. This person-centered style of religious authority is implicit in the teachings and identity of the scriptural sources of the Kulam!rga, a complex of traditions that developed out of more esoteric branches of tantric "aivism. For convenience sake, we name this model of religious authority a “Kaula idiom.” The Kaula idiom is contrasted with a highly influential notion of revelation as eternal and authorless, advanced by orthodox interpreters of the Veda, and other Indian traditions that invested the words of sages and seers with great authority. -

Twenty-Third International Congress of Vedanta August 10-13, 2017

Twenty - Third International Congress of Vedanta August 10 - 13, 2017 On August 10 - 13, 2017 the Twenty - Third International Congress of Vedanta was hosted by T he Center for Indic Studies, University of Massachusetts, Dartmouth, USA in collaboration with the Institute of Advanced Sciences, Dartmouth, USA . The inauguration session started in the morning of first day with Vedic c hanting performed by Swami Yogatmananda, Vedanta Society of Providence, and Swami Atmajnanananda, Vedanta Center of Greater Washington , DC . Welcome address and i ntroduction presented by Conference Director Prof. Sukalyan Sengupta, University of Massachusetts , Dartmouth. Founding Director, Vedanta Congress Prof. S.S. Ramarao Pappu was felicitated in this session. Conference started with an inaugural l ecture by Mr. Rajeev Srinivasan on “ Leveraging the Grand Dharmic Narrative for Soft Power ”. Dr. Alex Hankey, SVYASA Bangalore and Dr. Makarand Paranjape, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New D elhi were the keynote speakers during this inaugural session . They deliver ed their talk s on “ Synthesizing Vedic and Modern Theories to Explain Cognition of Forms ” and “ Vedanta and Aesthetics ” , respectively. This session was concluded under the chairmanship of Prof. Raghwendra P . Singh, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, India. Inaugural Session, 23 rd International Vedanta Congress The Vedanta Congress continues its tradition of bringing scholars of Indic traditions from India and the West together on a platform nearly from three decades. Delegates from various -

Brill's Encyclopedia of Hinduism

Brill’s Encyclopedia of Hinduism HANDBOOK OF ORIENTAL STUDIES HANDBUCH DER ORIENTALISTIK SECTION TWO INDIA edited by J. Bronkhorst A. Malinar VOLUME 22/5 Brill’s Encyclopedia of Hinduism Volume V: Religious Symbols Hinduism and Migration: Contemporary Communities outside South Asia Some Modern Religious Groups and Teachers Edited by Knut A. Jacobsen (Editor-in-Chief ) Associate Editors Helene Basu Angelika Malinar Vasudha Narayanan Leiden • boston 2013 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Brill’s encyclopedia of Hinduism / edited by Knut A. Jacobsen (editor-in-chief); associate editors, Helene Basu, Angelika Malinar, Vasudha Narayanan. p. cm. — (Handbook of oriental studies. Section three, India, ISSN 0169-9377; v. 22/5) ISBN 978-90-04-17896-0 (hardback : alk. paper) 1. Hinduism—Encyclopedias. I. Jacobsen, Knut A., 1956- II. Basu, Helene. III. Malinar, Angelika. IV. Narayanan, Vasudha. BL1105.B75 2009 294.503—dc22 2009023320 ISSN 0169-9377 ISBN 978 90 04 17896 0 Copyright 2013 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Global Oriental, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers and Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Brill provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. Fees are subject to change. Printed in the Netherlands Table of Contents, Volume V Prelims Preface .............................................................................................................................................. -

Issues in Indian Philosophy and Its History

4 ISSUESININDIAN PHILOSOPHY AND ITS HISTORY 4.1 DOXOGRAPHY AND CATEGORIZATION Gerdi Gerschheimer Les Six doctrines de spéculation (ṣaṭtarkī) Sur la catégorisation variable des systèmes philosophiques dans lInde classique* ayam eva tarkasyālaņkāro yad apratişţhitatvaņ nāma (Śaģkaraad Brahmasūtra II.1.11, cité par W. Halbfass, India and Europe, p. 280) Les sixaines de darśana During the last centuries, the six-fold group of Vaiśeşika, Nyāya, Sāņkhya, Yoga, Mīmāņ- sā, and Vedānta ( ) hasgained increasing recognition in presentations of Indian philosophy, and this scheme of the systems is generally accepted today.1 Cest en effet cette liste de sys- tèmes philosophiques (darśana) quévoque le plus souvent, pour lindianiste, le terme şađ- darśana. Il est cependant bien connu, également, que le regroupement sous cette étiquette de ces six systèmes brahmaniques orthodoxes est relativement récent, sans doute postérieur au XIIe siècle;2 un survol de la littérature doxographique sanskrite fait apparaître quil nest du reste pas le plus fréquent parmi les configurations censées comprendre lensemble des sys- tèmes.3 La plupart des doxographies incluent en effet des descriptions des trois grands sys- tèmes non brahmaniques, cest-à-dire le matérialisme,4 le bouddhisme et le jaïnisme. Le Yoga en tant que tel et le Vedānta,par contre, sont souvent absents de la liste des systèmes, en particulier avant les XIIIe-XIVe siècles. Il nen reste pas moins que les darśana sont souvent considérés comme étant au nombre de six, quelle quen soit la liste. La prégnance de cette association, qui apparaît dès la première doxographie, le fameux Şađdarśanasamuccaya (Compendium des six systèmes) du jaina Haribhadra (VIIIe s. -

Debashish Banerji Makarand R. Paranjape Editors Critical Posthumanism and Planetary Futures Critical Posthumanism and Planetary Futures Debashish Banerji • Makarand R

Debashish Banerji Makarand R. Paranjape Editors Critical Posthumanism and Planetary Futures Critical Posthumanism and Planetary Futures Debashish Banerji • Makarand R. Paranjape Editors Critical Posthumanism and Planetary Futures 123 Editors Debashish Banerji Makarand R. Paranjape California Institute of Integral Studies Jawaharlal Nehru University San Francisco, CA New Delhi USA India ISBN 978-81-322-3635-1 ISBN 978-81-322-3637-5 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-81-322-3637-5 Library of Congress Control Number: 2016947189 © Springer India 2016 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. Printed on acid-free paper This Springer imprint is published by Springer Nature The registered company is Springer (India) Pvt. -

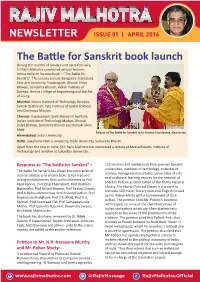

The Battle for Sanskrit Book Launch

NEWSLETTER ISSUE 01 | APRIL 2016 The Battle for Sanskrit book launch During the months of January and early February, Sri Rajiv Malhotra conducted various lectures across India on his new book – “The Battle for Sanskrit”. The venues include Bangalore: Karnataka Samskrit University, Yuvabrigade, Bharati Vidya Bhavan, Samskrita Bharati, Indian Institute of Science, Amrita College of Engineering and the Art of Living. Mumbai: Indian Institute of Technology Bombay, Samskrita Bharati, Tata Institute of Social Sciences and Chinmaya Mission. Chennai: Kuppuswami Sastri Research Institute, Indian Institute of Technology Madras, Bharati Vidya Bhavan, Samskrita Bharati and Ramakrishna Mutt. Release of The Battle for Sanskrit at Sri Krishna Vrundavana, New Jersey Ahmedabad: Indus University. Delhi: Jawaharlal Nehru University, Delhi University, Samskrita Bharati. Apart from the tour in India, Shri Rajiv Malhotra has conducted a lecture at Massachusetts Institute of Technology and another at Columbia University. Response to “The Battle for Sanskrit”:- 132 scholars and intellectuals from premier Sanskrit universities, institutes of technology, institutes of The Battle for Sanskrit has drawn the admiration of science, management institutes, universities of arts several scholars and intellectuals. It has received and traditional learning centres for the removal of strong endorsements from such luminaries as Prof Sheldon Pollock as Chief Editor of the Murty Classical Kapil Kapoor, Prof Dilip Chakrabarti, Prof Roddam Library. The Murty Classical Library is a project to Narasimha, Prof Arvind Sharma, Prof Pankaj Chande, translate 500 Indian literary texts into English funded Prof K Ramasubramanian, Prof R Vaidyanathan, Prof by Mr. Rohan Murty with a commitment of $5.6 Dayananda Bharghava, Prof S.R. Bhatt, Prof K.S. -

Secondary Indian Culture and Heritage

Culture: An Introduction MODULE - I Understanding Culture Notes 1 CULTURE: AN INTRODUCTION he English word ‘Culture’ is derived from the Latin term ‘cult or cultus’ meaning tilling, or cultivating or refining and worship. In sum it means cultivating and refining Ta thing to such an extent that its end product evokes our admiration and respect. This is practically the same as ‘Sanskriti’ of the Sanskrit language. The term ‘Sanskriti’ has been derived from the root ‘Kri (to do) of Sanskrit language. Three words came from this root ‘Kri; prakriti’ (basic matter or condition), ‘Sanskriti’ (refined matter or condition) and ‘vikriti’ (modified or decayed matter or condition) when ‘prakriti’ or a raw material is refined it becomes ‘Sanskriti’ and when broken or damaged it becomes ‘vikriti’. OBJECTIVES After studying this lesson you will be able to: understand the concept and meaning of culture; establish the relationship between culture and civilization; Establish the link between culture and heritage; discuss the role and impact of culture in human life. 1.1 CONCEPT OF CULTURE Culture is a way of life. The food you eat, the clothes you wear, the language you speak in and the God you worship all are aspects of culture. In very simple terms, we can say that culture is the embodiment of the way in which we think and do things. It is also the things Indian Culture and Heritage Secondary Course 1 MODULE - I Culture: An Introduction Understanding Culture that we have inherited as members of society. All the achievements of human beings as members of social groups can be called culture. -

The Case for Sanskrit As India's National Language by Makarand

The Case for Sanskrit as India’s National Language By Makarand Paranjape August 2012 This paper discusses in depth the role and the potential of Sanskrit in India’s cultural and national landscape. Reproduced with the author’s permission, it has been published in Sanskrit and Other Indian Languages , ed. Shashiprabha Kumar (New Delhi: D. K. Printworld, 2007), pp. 173- 200. “Sanskrit is the thread on which the pearls of the necklace of Indian culture are strung; break the thread and all the pearls will be scattered, even lost forever.” Dr. Lokesh Chandra Introduction I had first heard from my friends in the Sri Aurobindo Ashram, Pondicherry, that the Mother wanted Sanskrit to be made the national language of India. Indeed, Sanskrit is taught from childhood not only in the ashram schools, but also at Auroville, the comm unity that the Mother founded. On 11th November 1967, the Mother said: “ Sanskrit! Everyone should learn that. Especially everyone who works here should learn that….” 1 Because some degree of confusion persisted over the Mother’s and Sri Aurobindo’s views on the topic, a more direct question was put to the former on 4 October 1971: On certain issues where You and Sri Aurobindo have given direct answers, we [Sri Aurobindo's Action] are also specific, as for instance... on the language issue where You have said for the country that (1) the regional language should be the medium of instruction, (2) Sanskrit should be the national language, and (3) English should be the international language. Are we correct in giving these replies to such questions? Yes. -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

1 0 0 1 18AVP211 Amrita Values Programme II 1 0 0 1

18AVP201/Amrita Values Programme I/ 1 0 0 1 18AVP211 Amrita Values Programme II 1 0 0 1 Amrita University's Amrita Values Programme (AVP) is a new initiative to give exposure to students about richness and beauty of Indian way of life. India is a country where history, culture, art, aesthetics, cuisine and nature exhibit more diversity than nearly anywhere else in the world. Amrita Values Programmes emphasize on making students familiar with the rich tapestry of Indian life, culture, arts, science and heritage which has historically drawn people from all over the world. Students shall have to register for any two of the following courses, one each in the third and the fourth semesters, which may be offered by the respective school during the concerned semester. Courses offered under the framework of Amrita Values Programmes I and II Message from Amma’s Life for the Modern World Amma’s messages can be put to action in our life through pragmatism and attuning of our thought process in a positive and creative manner. Every single word Amma speaks and the guidance received in on matters which we consider as trivial are rich in content and touches the very inner being of our personality. Life gets enriched by Amma’s guidance and She teaches us the art of exemplary life skills where we become witness to all the happenings around us still keeping the balance of the mind. Lessons from the Ramayana Introduction to Ramayana, the first Epic in the world – Influence of Ramayana on Indian values and culture – Storyline of Ramayana – Study of leading characters in Ramayana – Influence of Ramayana outside India – Relevance of Ramayana for modern times. -

IAT Delhi-Library Books

ISHWAR ASHRAM TRUST -- LIBRARY CATALAGUE BOOKS RUN DATE: 06-17-2012 12:37:59 TITLE AUTHOR EDITED/COMMENTARY BY YEAR OF NOS RACK PUBLICATION TULSI - HOLY BASIL - (A YASH RAI 1 R008S01 HREB) VATULANATHA SUTRA SWAMI LAKSHMAN JOO PROF. N. K. GURTOO, 1996 2 R002S01 MAHARAJ PROF. M. L. KUKILOO 5 AMERICAN MASTERS O'HENRY, JACK LONDON, 2003 1 R006S01 HENRY JAMES, MARK TWAIN, EDGAR ALLAN POE 5 BRITISH MASTERS OSCAR WILDE, HECTOR 2003 1 R006S01 HUGH MINRO, D. H. LAWERENCE, JOSEPH CONRAD, CHARLES DICKENS 5 FRENCH MASTERS GUY DE MAUPASSANT, 2003 1 R0065S01 HONORE DE BALZAC, VICTOR HUGO, ANATOLE FRANCE, PIERRE LOUYS A BRIEF HISTORY OF MICHEAL SCHNEIDER BARRIE SELMAN 1991 1 R008S01 THE GERMAN TADE UNIONS A BRIEF HSTORY OF STEPHN W HAWKING 1989 1 R006S02 TIME A DICTIONARY OF FLORENCE ELLIOTT, 1957 1 R008S02 POLITICS MICHAEL SUMMERSKILL A FIERY PATRIOT DR. HAI DEV SHARMA 2003 1 R007S03 SPEAKS - INTERVIEW WITH SURENDRA NATH JAUHAR A GARLAND OF SURENDRA NATH 2004 2 R007S02 TRIBUTES JAUHAR "FAQUIR" A GLIMPSE INTO THE G. N. MUJOO 1 R010S02 HINDU RELIGION, PHILOSOPHY AND EXPLOITS OF SHRI RAMA A HISTORY OF KASHMIRI JUSTICE JIA LAL KILAM ADVAITAVADINI KAUL 2003 4 R006S01 PANDITS A JOURNEY THROUGH JAYANT NARLIKAR SUDHIR DAR 2005 1 R008S03 THE UNIVERSE A LET'S GO TRAVEL 2004 1 R003S02 GUIDE INDIA AND NEPAL A LIST OF BOOKS ON 2 R003S01 KASHMIR SHAIVISM ISHWAR ASHRAM TRUST -- LIBRARY CATALAGUE BOOKS RUN DATE: 06-17-2012 12:37:59 TITLE AUTHOR EDITED/COMMENTARY BY YEAR OF NOS RACK PUBLICATION A MANUAL OF SELF SWAMI CHINMAYANANDA 2003 1 R007S01 UNFOLDMENT A MESSAGE FROM DR.