" Style Upon Style": the Handmaid's Tale As a Palimpsest of Genres

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hanging on to the Edges Hanging on to the Edges

DANIEL NETTLE Hanging on to the Edges Hanging on to the Edges Essays on Science, Society and the Academic Life D ANIEL Essays on Science, Society I love this book. I love the essays and I love the overall form. Reading these essays feels like entering into the best kind of intellectual conversati on—it makes me want and the Academic Life to write essays in reply. It makes me want to get everyone else reading it. I almost N never feel this enthusiasti c about a book. ETTLE —Rebecca Saxe, Professor of Cogniti ve Science at MIT What does it mean to be a scien� st working today; specifi cally, a scien� st whose subject ma� er is human life? Scien� sts o� en overstate their claim to certainty, sor� ng the world into categorical dis� nc� ons that obstruct rather than clarify its complexi� es. In this book Daniel Ne� le urges the reader to unpick such DANIEL NETTLE dis� nc� ons—biological versus social sciences, mind versus body, and nature versus nurture—and look instead for the for puzzles and anomalies, the points of Hanging on to the Edges connec� on and overlap. These essays, converted from o� en humorous, some� mes autobiographical blog posts, form an extended medita� on on the possibili� es and frustra� ons of the life scien� fi c. Pragma� cally arguing from the intersec� on between social and biological sciences, Ne� le reappraises the virtues of policy ini� a� ves such as Universal Basic Income and income redistribu� on, highligh� ng the traps researchers and poli� cians are liable to encounter. -

Company Overview

Gilead Sciences Advancing Therapeutics. Improving Lives. Company Overview Gilead Sciences, Inc. is a research-based biopharmaceutical Key Moments in Our History company that discovers, develops and commercializes innovative medicines in areas of unmet medical need. With each new 1987 Gilead founded discovery and investigational drug candidate, we seek to improve AmBisome® approved (Europe) the care of patients living with life-threatening diseases around the 1990 world. Gilead’s therapeutic areas of focus include HIV/AIDS, liver 1991 Nucleotides in-licensed from diseases, cancer and inflammation, and serious respiratory and IOCB Rega cardiovascular conditions. 1996 Vistide® approved Our portfolio of 18 marketed 1999 NeXstar acquired; products contains a number Tamiflu® approved of category firsts, including complete treatment regimens 2001 Viread® approved for HIV and chronic hepatitis Hepsera® approved C infection available in once- 2002 daily single pills. Gilead’s 2003 Triangle Pharmaceuticals acquired; portfolio includes Harvoni® Emtriva® approved (ledipasvir 90 mg/sofosbuvir ® ® 400 mg) for chronic hepatitis C, 2004 Macugen , Truvada approved which is a complete antiviral 2006 Atripla®, Ranexa® approved; treatment regimen in a single Corus, Raylo, Myogen acquired tablet that provides high cure ® rates and a shortened course 2007 Letairis approved; Cork, Ireland, Harvoni, Gilead’s once-daily single of therapy for many patients. manufacturing facility acquired tablet HCV regimen. from Nycomed ® 2008 Lexiscan , Viread® for hepatitis B Nearly 30 Years of Growth approved Gilead was founded in 1987 in Foster City, California. Since CV Therapeutics acquired then, Gilead has become a leading biopharmaceutical company 2009 ® with a rapidly expanding product portfolio, a growing pipeline of 2010 Cayston approved; investigational drugs and more than 7,000 employees in offices CGI Pharmaceuticals acquired across six continents. -

The Significance of the Biblical Dead Sea Scrolls

Journal of Theology of Journal Southwestern dead sea scrolls sea dead SWJT dead sea scrolls Vol. 53 No. 1 • Fall 2010 Southwestern Journal of Theology • Volume 53 • Number 1 • Fall 2010 The Significance of the Biblical Dead Sea Scrolls Peter W. Flint Trinity Western University Langley, British Columbia [email protected] Brief Comments on the Dead Sea Scrolls and Their Importance On 11 April 1948, the Dead Sea Scrolls were announced to the world by Millar Burrows, one of America’s leading biblical scholars. Soon after- wards, famed archaeologist William Albright made the extraordinary claim that the scrolls found in the Judean Desert were “the greatest archaeological find of the Twentieth Century.” A brief introduction to the Dead Sea Scrolls and what follows will provide clear indications why Albright’s claim is in- deed valid. Details on the discovery of the scrolls are readily accessible and known to most scholars,1 so only the barest comments are necessary. The discovery begins with scrolls found by Bedouin shepherds in one cave in late 1946 or early 1947 in the region of Khirbet Qumran, about one mile inland from the western shore of the Dead Sea and some eight miles south of Jericho. By 1956, a total of eleven caves had been discovered at Qumran. The caves yielded various artifacts, especially pottery. The most impor- tant find was scrolls (i.e. rolled manuscripts) written in Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek, the three languages of the Bible. Almost 900 were found in the Qumran caves in about 25,000–50,000 pieces,2 with many no bigger than a postage stamp. -

TURKEY BASIC COUNTRY DATA Total Population

TURKEY BASIC COUNTRY DATA Total Population: 72,752,325 Population 0-14 years: 26% Rural population: 30% Population living under USD 1.25 a day: 2.7% Population living under the national poverty line: 18.1% Income status: Upper middle income economy Ranking: High human development (ranking 92) Per capita total expenditure on health at average exchange rate (US dollar): 571 Life expectancy at birth (years): 73 Healthy life expectancy at birth (years): 62 BACKGROUND INFORMATION The first case of VL in Turkey was reported from Trabzon, in the eastern part of the Black Sea Region, in 1916; the second from Izmir, in the Aegean Region, in 1918. VL is endemic, with sporadic cases reported from 38 of 81 provinces (in 2008, there were less than 10 cases). Most cases occur at the Armenian border, in the Aegean, Mediterranean, and Central Anatolia Regions [1,2]. Dogs seem to be the main animal reservoir with a high seroprevalence of over 20% in some of the endemic regions [3]. CL is caused by L. tropica and is more prevalent in southeastern Anatolia [4], where 96% of cases are located, central Anatolia, the western regions, and, less frequently, in the Mediterranean and Aegean Regions [1,5,6]. In Sanliurfa, southeastern Anatolia, the number of CL cases reported from 1981 to 2000 was 22,335. The reported incidence reached a peak in 1994, with 4,185 cases. There has been a considerable reduction in the number of reported cases from 1995 onwards [7]. A recent upsurge of CL cases in the southeastern Anatolia Region is attributed to the environmental impact of a big irrigation project (Güneydoğu Anadolu Projesi-GAP) [8]. -

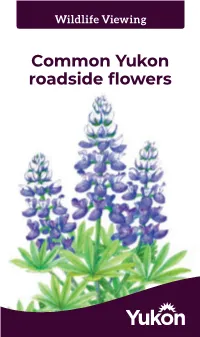

Wildlife Viewing

Wildlife Viewing Common Yukon roadside flowers © Government of Yukon 2019 ISBN 987-1-55362-830-9 A guide to common Yukon roadside flowers All photos are Yukon government unless otherwise noted. Bog Laurel Cover artwork of Arctic Lupine by Lee Mennell. Yukon is home to more than 1,250 species of flowering For more information contact: plants. Many of these plants Government of Yukon are perennial (continuously Wildlife Viewing Program living for more than two Box 2703 (V-5R) years). This guide highlights Whitehorse, Yukon Y1A 2C6 the flowers you are most likely to see while travelling Phone: 867-667-8291 Toll free: 1-800-661-0408 x 8291 by road through the territory. Email: [email protected] It describes 58 species of Yukon.ca flowering plant, grouped by Table of contents Find us on Facebook at “Yukon Wildlife Viewing” flower colour followed by a section on Yukon trees. Introduction ..........................2 To identify a flower, flip to the Pink flowers ..........................6 appropriate colour section White flowers .................... 10 and match your flower with Yellow flowers ................... 19 the pictures. Although it is Purple/blue flowers.......... 24 Additional resources often thought that Canada’s Green flowers .................... 31 While this guide is an excellent place to start when identi- north is a barren landscape, fying a Yukon wildflower, we do not recommend relying you’ll soon see that it is Trees..................................... 32 solely on it, particularly with reference to using plants actually home to an amazing as food or medicines. The following are some additional diversity of unique flora. resources available in Yukon libraries and bookstores. -

Self, Narrative, and Performative Femininity As Subversion and Weapon in the Handmaid’S Tale

A Woman’s Place is in the Resistance; Self, Narrative, and Performative Femininity as Subversion and Weapon in The Handmaid’s Tale A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Millersville University of Pennsylvania In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Art By Courtney Landis September 2018 2 Approval Page This Thesis for the Master of Arts Degree by Courtney M. Landis Has been approved on behalf of the Graduate School by Thesis Committee: (signatures on file) Dr. Carla A. Rineer Research Advisor Dr. Kerrie Farkas Committee Member Dr. Katarzyne Jakubiak Committee Member September 21, 2018 Date 3 Preface The basis for this paper originally stemmed from my interest feminist theory, women’s literature, and contemporary literature. Margaret Atwood is an acclaimed writer, and her 1985 novel The Handmaid’s Tale is iconic and only growing in influence. A paper examining the gender structures of The Handmaid’s Tale and how they describe life in a patriarchal culture seemed like a natural fit for both the novel and my own research interests. Despite years of undergraduate and graduate work in English, I have unfortunately never had the opportunity to take a class specifically in women’s literature or feminist theory, and I appreciate the opportunity to explore those areas in my work on this thesis. Though I began a version of this thesis in summer of 2016, after the results of the 2016 presidential election, I was moved to alter the focus of this paper to examine the ways in which Offred performs gender as a method of survival as well as resistance. -

Ideologija Republike Gilead U "Sluškinjinoj Priči" M. Atwood

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Repository of Josip Juraj Strossmayer University of Osijek Sveučilište J. J. Strossmayera u Osijeku Filozofski fakultet Osijek Dvopredmetni sveučilišni diplomski studij engleskog jezika i književnosti – nastavnički smjer i hrvatskog jezika i književnosti – nastavnički smjer Aleksandra Balenović Ideologija Republike Gilead u "Sluškinjinoj priči" M. Atwood Diplomski rad doc. dr. sc. Ljubica Matek Osijek, 2018. Sveučilište J. J. Strossmayera u Osijeku Filozofski fakultet Osijek Dvopredmetni sveučilišni diplomski studij engleskog jezika i književnosti – nastavnički smjer i hrvatskog jezika i književnosti – nastavnički smjer Aleksandra Balenović Ideologija Republike Gilead u "Sluškinjinoj priči" M. Atwood Diplomski rad Znanstveno područje: humanističke znanosti Znanstveno polje: filologija Znanstvena grana: anglistika doc. dr. sc. Ljubica Matek Osijek, 2018. University of J.J. Strossmayer in Osijek Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences MA Programme in English Language and Literature (Education Studies) and Croatian Language and Literature (Education Studies) Aleksandra Balenović The Ideology of the Republic of Gilead in M. Atwood's The Handmaid's Tale Master's Thesis Ljubica Matek, Ph.D., Assistant Professor Osijek, 2018 University of J.J. Strossmayer in Osijek Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences MA Programme in English Language and Literature (Education Studies) and Croatian Language and Literature (Education Studies) Aleksandra Balenović -

The Majesty and Mystery of the Dead Sea Scrolls

The Majesty and Mystery of the Dead Sea Scrolls Joel M. Hoffman, PhD http://www.lashon.net/JMH CAJE 32 Washington University, St. Louis, MO 1 The Cast Khalil Musa, Jum'a Mohammed, and Mohammed el-Dhib Ð Ta'amireh Bedouin Jalil ªKandoº Iskandar Shalim Ð antiquities dealer Athanasius Yeshue Samuel Ð Archimandrite of Saint Mark in Jerusalem Eliezer Sukenik Ð professor at Hebrew University John Trever Ð research student at ASOR and amateur pho- tographer Yigael Yadin Ð archaeologist and IDF chief of staff (E. Sukenik's son) Lankester Harding Ð director of the Department of Antiq- uities of Jordan ¡ Roland de Vaux Ð director of Ecole Biblique et Archeologique Francaise¢ Ben Zion Wacholder Ð professor at HUC-JIR in Cincinnati Martin Abegg Ð graduate student working with Professor Wacholder 1 2 The Plot 3 The Scrolls Rules Halakhic Texts Eschatological Literature Exegetical Literature Para-Biblical Literature Poetic Texts Liturgical Texts Astronomical Texts, Calendars, & Horoscopes Biblical Material The Copper Scroll 4 Psalms 4.1 4Q88 Let heaven and earth exult. May all the stars of dusk exult with them. Rejoice, Judah, rejoice greatly! Rejoice greatly and de- light greatly, celebrate your celebrations and ful®ll your vows, for there is no evil1 in you. Lift up your hand, strengthen your right hand, for your enemies will perish and all evil[do]ers scatter. You, Adonai, are forever, and your glory is forever.... 4.2 Psalms [Psalm 96] Let heaven rejoice and earth delight... [Psalm 92] When the wicked sprout like weeds and all evildoers ¯ourish, it is that they be destroyed forever. -

List of Works by Margaret Atwood

LIST OF WORKS BY MARGARET ATWOOD Note: This bibliography lists Atwood’s novels, short fiction, poetry, and nonfiction books. It is current as of 2019. Dates in parentheses re- fer to the initial date of publication; when there is variance across countries, the date refers to the Canadian publication. We have used standard abbreviations for Atwood’s works across the essays; how- ever, contributors have used a range of editions (Canadian, American, British, etc.), reflecting the wide circulation of Atwood’s writing. For details on the specific editions consulted by contributors, please see the bibliography immediately following each essay. For a complete bibliography of Atwood’s works, including small press editions, children’s books, scripts, and edited volumes, see http://mar- garetatwood.ca/full-bibliography-2/ Novels EW The Edible Woman (1969) Surf. Surfacing (1972) LO Lady Oracle (1976) LBM Life Before Man (1979) BH Bodily Harm (1981) HT The Handmaid’s Tale (1985) CE Cat’s Eye (1988) RB The Robber Bride (1993) AG Alias Grace (1996) BA The Blind Assassin (2000) O&C Oryx and Crake (2003) P The Penelopiad (2005) YF Year of the Flood (2009) MA MaddAddam (2013) HGL The Heart Goes Last (2015) HS Hag-Seed (2016) Test. The Testaments (2019) ix x THE BIBLE AND MARGARET ATWOOD Short Fiction DG Dancing Girls (1977) MD Murder in the Dark (1983) BE Bluebeard’s Egg (1983) WT Wilderness Tips (1991) GB Good Bones (1992) GBSM Good Bones and Simple Murders (1994) Tent The Tent (2006) MD Moral Disorder (2006) SM Stone Mattress (2014) Poetry CG The Circle -

Training to Strengthen National Drug Observatories in Latin America and the Caribbean: Fourth Edition

Training to Strengthen National Drug observatories in Latin America and the Caribbean: Fourth Edition Cartagena, Colombia - June 25-27, 2019 Tuesday – June 25 Time Activity 08:30 - 09:00 Registration of participants Registration of participants. Opening 09:00 - 09:30 Registration of participants.Registration of participants. Rafael Parada, Unit chief, Supply Reduction Unit, CICAD/OAS. Pernell Clarke, Specialist, Inter-American Observatory on Drugs, CICAD/OAS. Sofía Mata Modrón, Director of the Spanish Agency for International Development Cooperation (AECID) in Cartagena, Colombia. 09:30 - 9:45 Inter-American Observatory on Drugs and Supply Reduction Unit of CICAD - Introduction of the participants. - Presentation of meeting objectives and the work methodology. 9:45 – 10:30 Report on Drug Use in the Americas 2019 Presenter: Juan Carlos Araneda, Project Officer OID/CICAD/OAS. 10:30 – 11:00 Break – Photograph with all the participants. Panel Discussion: Reports and publications on supply control and/or the 11:00 – 11:45 market for illicit drugs (scope and methods). Leah-Perle Bloomenstein, DEA - Intelligence Analyst, National Strategic Intelligence Unit. Hernán Epstein, UNODC – Statistics, Data Development and Dissemination Unit, Research and Trends Analysis Section (Via Skype from Vienna). Moderator: Pernell Clarke, Specialist OID/CICAD/OAS. 11:45 – 13:00 Experience in the collection of information on drug supply in countries of the Americas. Tiago Martín, presentation on Argentina. Avajean Sánchez, presentation on Belize. Gabriela Reyes, presentation on Bolivia. Jorge Muñoz Bravo, presentation on Chile. Moderator: Juan Carlos Araneda, Project Officer, OID/CICAD/OAS. 13:00 – 14:00 Lunch 14:00 – 15:30 Experience in the collection of information on drug supply in countries of the Americas. -

Storied Memories: Memory As Resistance in Contemporary Women's Literature Sarah Katherine Foust Vinson Loyola University Chicago

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Loyola eCommons Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2010 Storied Memories: Memory as Resistance in Contemporary Women's Literature Sarah Katherine Foust Vinson Loyola University Chicago Recommended Citation Foust Vinson, Sarah Katherine, "Storied Memories: Memory as Resistance in Contemporary Women's Literature" (2010). Dissertations. Paper 176. http://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/176 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 2010 Sarah Katherine Foust Vinson LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO STORIED MEMORIES: MEMORY AS RESISTANCE IN CONTEMPORARY WOMEN’S LITERATURE A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY PROGRAM IN ENGLISH BY SARAH K. FOUST VINSON CHICAGO, IL MAY 2010 Copyright by Sarah K. Foust Vinson, 2010 All rights reserved. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank all of the people who made this dissertation possible, starting with my wonderful professors in the English Department at Loyola University Chicago. Dr. Paul Jay encouraged me to integrate my interest in the psychology of memory with the field of literature, and he always provided a kind word when I needed it most. Dr. Harveen Mann challenged me to consider the larger implications of my work and supported me throughout the process with an encouraging smile and a positive attitude. -

A Collection of Poems and Songs) Del Vaugh Schmidt Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1989 Waitin' for the blow (a collection of poems and songs) Del Vaugh Schmidt Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Poetry Commons Recommended Citation Vaugh Schmidt, Del, "Waitin' for the blow (a collection of poems and songs)" (1989). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 204. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/204 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. -------- Waitin' for the blow (A collection of poems and songs) by Del Vaughn Schmidt A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department: English Major: English (Creative Writing) Approved: Signature redacted for privacy //"' Signature redacted for privacy Signature redacted for privacy For College Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 1989 ----------- ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page PREFACE iv POEMS 1 Feeding the Horses 2 The Barnyard 3 Colorado, Summer 1979 5 Arrival 8 Aliens 10 Communicating 12 Home 13 Jeff 15 Waitin' for the Blow 17 Real Surreal 21 Stove Wall 22 Positive 25 Playin' 26 Maybe it's the Music 27 SONGS 31 Have Another (for Colorado) 32 Wake Up 34 Unemployment Blues 36 Players 37 Train We're On 38 Institution 40 iii Farmer's Lament 42 Space Blues 44 You Would Have Made the Day 45 Four Nights in a Row 47 Helpless Bound 49 Carpenter's Blues 50 Hills 51 iv PREFACE Up to the actual point of writing this preface, I have never given much deep thought as to the difference between writing song lyrics and poetry.