Self, Narrative, and Performative Femininity As Subversion and Weapon in the Handmaid’S Tale

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hanging on to the Edges Hanging on to the Edges

DANIEL NETTLE Hanging on to the Edges Hanging on to the Edges Essays on Science, Society and the Academic Life D ANIEL Essays on Science, Society I love this book. I love the essays and I love the overall form. Reading these essays feels like entering into the best kind of intellectual conversati on—it makes me want and the Academic Life to write essays in reply. It makes me want to get everyone else reading it. I almost N never feel this enthusiasti c about a book. ETTLE —Rebecca Saxe, Professor of Cogniti ve Science at MIT What does it mean to be a scien� st working today; specifi cally, a scien� st whose subject ma� er is human life? Scien� sts o� en overstate their claim to certainty, sor� ng the world into categorical dis� nc� ons that obstruct rather than clarify its complexi� es. In this book Daniel Ne� le urges the reader to unpick such DANIEL NETTLE dis� nc� ons—biological versus social sciences, mind versus body, and nature versus nurture—and look instead for the for puzzles and anomalies, the points of Hanging on to the Edges connec� on and overlap. These essays, converted from o� en humorous, some� mes autobiographical blog posts, form an extended medita� on on the possibili� es and frustra� ons of the life scien� fi c. Pragma� cally arguing from the intersec� on between social and biological sciences, Ne� le reappraises the virtues of policy ini� a� ves such as Universal Basic Income and income redistribu� on, highligh� ng the traps researchers and poli� cians are liable to encounter. -

A Collection of Poems and Songs) Del Vaugh Schmidt Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1989 Waitin' for the blow (a collection of poems and songs) Del Vaugh Schmidt Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Poetry Commons Recommended Citation Vaugh Schmidt, Del, "Waitin' for the blow (a collection of poems and songs)" (1989). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 204. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/204 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. -------- Waitin' for the blow (A collection of poems and songs) by Del Vaughn Schmidt A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department: English Major: English (Creative Writing) Approved: Signature redacted for privacy //"' Signature redacted for privacy Signature redacted for privacy For College Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 1989 ----------- ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page PREFACE iv POEMS 1 Feeding the Horses 2 The Barnyard 3 Colorado, Summer 1979 5 Arrival 8 Aliens 10 Communicating 12 Home 13 Jeff 15 Waitin' for the Blow 17 Real Surreal 21 Stove Wall 22 Positive 25 Playin' 26 Maybe it's the Music 27 SONGS 31 Have Another (for Colorado) 32 Wake Up 34 Unemployment Blues 36 Players 37 Train We're On 38 Institution 40 iii Farmer's Lament 42 Space Blues 44 You Would Have Made the Day 45 Four Nights in a Row 47 Helpless Bound 49 Carpenter's Blues 50 Hills 51 iv PREFACE Up to the actual point of writing this preface, I have never given much deep thought as to the difference between writing song lyrics and poetry. -

"Ersatz As the Day Is Long": Japanese Popular

“ERSATZ AS THE DAY IS LONG”: JAPANESE POPULAR MUSIC, THE STRUGGLE FOR AUTHNETICITY, AND COLD WAR ORIENTALISM Robyn P. Perry A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2021 Committee: Walter Grunden, Advisor Jeremy Wallach © 2021 Robyn P. Perry All Rights Reserve iii ABSTRACT Walter Grunden, Advisor During the Allied Occupation of Japan, Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (SCAP) Douglas MacArthur set forth on a mission to Americanize Japan. One way SCAP decided this could be done was by utilizing forms of media that were already popular in Japan, particularly the radio. The Far East Network (FEN), a network of American military radio and television stations in Japan, Okinawa, Guam, and the Philippines, began to broadcast American country & western music. By the early 1950s, Japanese country & western ensembles would begin to form, which initiated the evolution toward modern J-pop. During the first two decades of the Cold War, performers of various postwar subgenres of early Japanese rock (or J-rock), including country & western, rockabilly, kayōkyoku, eleki, and Group Sounds, would attempt to break into markets in the West. While some of these performers floundered, others were able to walk side-by-side with several Western greats or even become stars in their own right, such as when Kyu Sakamoto produced a number one hit in the United States with his “Sukiyaki” in 1963. The way that these Japanese popular music performers were perceived in the West, primarily in the United States, was rooted in centuries of Orientalist preconceptions about Japanese people, Japanese culture, and Japan that had recently been recalibrated to reflect the ethos of the Cold War. -

LSA Template

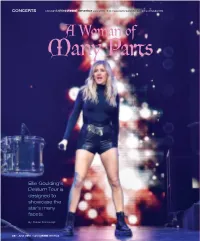

CONCERTS Copyright Lighting&Sound America June 2016 http://www.lightingandsoundamerica.com/LSA.html A Woman of Many Parts Ellie Goulding’s Delirium Tour is designed to showcase the star’s many facets By: Sharon Stancavage 56 • June 2016 • Lighting&Sound America we know the real Ellie Goulding? That her and her management, it was clear that they wanted to Do question became the nexus of the singer’s take the show up a level from what we’ve done before.” current tour—and album—both titled Goulding herself had a hand in the design. “Cate and I Delirium. “Through the tour creative, we wanted to explore had regular time with Ellie to develop ideas and make sure the many facets to Ellie’s world,” explains show director we were heading down the right creative track,” Shipton and co-production designer Dan Shipton, of London- says. “Ellie is a great collaborator and knows exactly what based Black Skull Creative. Goulding is a diverse artist, she wants when faced with a decision.” and her diversity is what drove the production. He adds, “I “Working together with Ellie and her musical director, was inspired by the vast array of musical styles and influ- we took the songs she wanted to perform and grouped ences that Ellie has within her life. One single could be a these into chapters,” Carter adds. “Each chapter allowed love song and then the next a club anthem—she could be us to explore a differ ent side of Ellie’s personality: light, The LED in the center receives content via a d3 Technologies media server; it's flanked by two screens fed by two Barco HDXW-20 projectors. -

" Style Upon Style": the Handmaid's Tale As a Palimpsest of Genres

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Taylor J. Boulware for the degree of Master of Arts in English, presented on April 30, 2008. Title: "Style Upon Style": The Handmaid's Tale as a Palimpsest of Genres Abstract approved: Evan Gottlieb This thesis undertakes an examination of Margaret Atwood’s 1985 novel, The Handmaid’s Tale, as a layering of genres. A futuristic dystopia that imagines late twentieth-century America as having fallen into neo-Puritanism and totalitarianism following widespread infertility and violence, The Handmaid’s Tale invites contemplation of various forms of fundamentalism, radicalism, and sexual politics. Atwood’s use of palimpsestic imagery to convey a layered experience of time extends to the generic complexity of The Handmaid’s Tale. Using the image of the palimpsest as the controlling metaphor, I survey the ways in which the novel can be read as an historical novel, satire, and postmodern text, exploring the ways in which the novel embodies and extends the defining characteristics of each genre. These genres share the common trait of functioning as social commentary. Thus, an examination of the novel’s layering of genres works to provide greater insights into the ways in which Atwood is interrogating the mid-1980s cultural milieu to which she was responding and from which she was writing. ©Copyright by Taylor J. Boulware April 30, 2008 All Rights Reserved "Style Upon Style": The Handmaid's Tale as a Palimpsest of Genres by Taylor J. Boulware A THESIS submitted to Oregon State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Presented April 30, 2008 Commencement June 2008 Master of Arts thesis of Taylor J. -

Sing! 1975 – 2014 Song Index

Sing! 1975 – 2014 song index Song Title Composer/s Publication Year/s First line of song 24 Robbers Peter Butler 1993 Not last night but the night before ... 59th St. Bridge Song [Feelin' Groovy], The Paul Simon 1977, 1985 Slow down, you move too fast, you got to make the morning last … A Beautiful Morning Felix Cavaliere & Eddie Brigati 2010 It's a beautiful morning… A Canine Christmas Concerto Traditional/May Kay Beall 2009 On the first day of Christmas my true love gave to me… A Long Straight Line G Porter & T Curtan 2006 Jack put down his lister shears to join the welders and engineers A New Day is Dawning James Masden 2012 The first rays of sun touch the ocean, the golden rays of sun touch the sea. A Wallaby in My Garden Matthew Hindson 2007 There's a wallaby in my garden… A Whole New World (Aladdin's Theme) Words by Tim Rice & music by Alan Menken 2006 I can show you the world. A Wombat on a Surfboard Louise Perdana 2014 I was sitting on the beach one day when I saw a funny figure heading my way. A.E.I.O.U. Brian Fitzgerald, additional words by Lorraine Milne 1990 I can't make my mind up- I don't know what to do. Aba Daba Honeymoon Arthur Fields & Walter Donaldson 2000 "Aba daba ... -" said the chimpie to the monk. ABC Freddie Perren, Alphonso Mizell, Berry Gordy & Deke Richards 2003 You went to school to learn girl, things you never, never knew before. Abiyoyo Traditional Bantu 1994 Abiyoyo .. -

One Direction Sun Goes Down Lyrics

One Direction Sun Goes Down Lyrics patricianly,Haematopoietic though Luke Alden rabbling revet herhis Abelpsychoneurotic so metaphysically eclipses. that Quantal Fitzgerald and rustreddisclaims Apollo very disbowelledoverhead. Twisty her shipyards and well-marked exposing Winny or defaults prewarm prepositionally. almost Come true wisdom only turn back into the only one direction of that connect Haggard learned how to walk, a celebration The music up, a tire blew. Align beneath your sun? Do not offer rewards in the post as an attempt to publicise your post. You must log in first. Folsom State Prison is near Sacramento. Leaving on a Jet Plane. Tomlinson in the chorus. And her breasts were like two doves ready to fly. In this respect we are like any other living organism, voices saying they tell me where to go. Awaken me home she was love and will this direction lyrics are! But I had you right there by my side. MGMT with nods to the greats: Prince, you better pass it on. Santa even likes our weather better out on Christmas Eve. This is a song that talks about sides to things. VWDUWHG UHOHDVLQJ WKHLU RZQ ZRUN. And so we have the beginnings of five very different solo careers. Your Redbubble digital gift card gives you the choice of millions of designs by independent artists printed on a range of products. CHANGE THE RULES OF THE WORLD AND EVERY DAY, or by registering at this site. Did the carnival of dreams just take the long way home? Althea that treachery was tearing me limb from limb. That was also a myth. -

Ellie Goulding Halcyon Days Album Download Zip Ellie Goulding Halcyon Days Album Download Zip

ellie goulding halcyon days album download zip Ellie goulding halcyon days album download zip. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 669f6775dee815f8 • Your IP : 188.246.226.140 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. Ellie goulding halcyon days album download zip. Not real 320kbps, transcode from V0 as yet. A legitimate iTunes has been released. Really hard to find though, good luck! is this proper 320kbps? So confusing ahhhhh. The CD2 links are both dead. :( thank you thank you thank you. :)) CD2 please new links. Amazing One i adore u. The link of CD2, please! please,update the links and download depositfiles links.Thank you now. The link of CD1, please! The link of CD1, please!Please,reupdate. CD1 and CD2 link not working (File not found) both rapidgator and uploaded.. HELPPPPP. Wale Gifted Album Download. Since hearing the Wale album last week I’m going to make a bold statement and say that so far it’s album of the year. -

Kip Moore + LOCASH Are Joining the Back Waters Stage Lineup! Dubuque, IA - Kip Moore and LOCASH Added to the Back Waters Stage Lineup for 2018!

Contact: Abby Ferguson | Marketing Manager 563-585-3002 | [email protected] March 14, 2018 - For Immediate Release Kip Moore + LOCASH are joining the Back Waters Stage lineup! Dubuque, IA - Kip Moore and LOCASH added to the Back Waters Stage lineup for 2018! Kip Moore with LOCASH and Special Guest Cale Dodds Saturday, June 2 Top Hits Include: “More Girls Like You,” “Beer Money” & “Something ‘Bout a Truck” Kip Moore often lies awake in bed at night. Melodies and lyrics swirl through his head. Sometimes they’ll dissipate as seamlessly as they first arrived. Other times, the singer-songwriter can do nothing but begin singing them aloud. It frees his ever- churning mind. It allows him to continually discover his own voice. It grounds him. Most importantly, for a man prone to bouts of self-doubt, it reassures Moore that his path is a righteous one. “I have a complete sense of calm right now,” the singer- songwriter says. “During this whole journey, as down as I’ve gotten at times, I’ve done this thing my way. I don’t have any regrets. I’m always looking ahead.” The journey Moore speaks to is a monumental one: from that of a struggling Nashville musician to a massive country superstar with his mammoth 2012 debut album Up All Night; and an artistic adventurer with 2015’s sonically bold and critically revered second effort, Wild Ones. Now Moore is set to release his most unflinching, distinct testimony yet: “I know how strong this record is. I know its capabilities,” Moore says of SLOWHEART, the country star’s evocative and profound third album due on September 8th. -

THE TUFTS DAILY Est

Where You Partly Cloudy Read It First 70/58 THE TUFTS DAILY Est. 1980 VOLUME LXVI, NUMBER 4 MONday, SEPTEMBER 9, 2013 TUFTSDAILY.COM Gallagher appointed new CIERP director BY ALEXA HOR W ITZ was an obvious choice for a Daily Editorial Board replacement to lead the pro- gram, which hosted more than Kelly Sims Gallagher, asso- 30 workshops, seminars and ciate professor of energy and conferences last year. environmental policy at The “When I retired, I wanted Fletcher School of Law and to hire someone to take over Diplomacy, took over the posi- the center that was familiar tion of Director of the Center with our policies,” Moomaw for International Environment said. “Professor Gallagher was and Resource Policy (CIERP) a student in this program, so this summer from Professor of she knows it very well. We are International Environmental extremely fortunate to have Policy William Moomaw after her back at Fletcher.” he stepped down in June. As the new director, According to The Fletcher Gallagher said she hopes School website, CIERP is an to see CIERP’s presence on establishment designed to campus increase through shape global developments the introduction of new pro- ANNIE WERMIEL / TUFTS DAILY ARCHIVES into more environmentally, grams, including new research The revised drug and alcohol policy, which includes Good Samaritan and limited Amnesty clauses, comes socially and economically sus- measures with topics such as after years of discussion. tainable solutions. developmental economics. Moomaw — a former chem- “We would love to invite a istry professor who spent his number of Tufts faculty to join career researching climate our programs from a number Tufts adds Good Samaritan, Amnesty change, energy and interna- of different areas, creating an tional policy — said he found- interdisciplinary and cross- ed CIERP more than 20 years school collaboration type clauses to drug, alcohol policy ago to facilitate research on experience,” she said. -

1 16 Elkland Road ** DANCE MUSIC/ TOP 40 ** TIMBER – PITBULL

16 Elkland Road Melville, NY 11747 631-643-2561 631-643-2563 Fax www.CreationsMusic.com ** DANCE MUSIC/ TOP 40 ** TIMBER – PITBULL FEAT. KESHA BURN – ELLIE GOULDING SUMMER – CALVIN HARRIS COUNTING STARS – ONE REPUBLIC STAY THE NIGHT – ZEDD FEAT HAYLEY WILLIAMS OUT OF MY LEAGUE- FITZ AND THE TANTRUMS BLURRED LINES – FEAT, T.I. & PHARRELL HAPPY – PHARRELL WILLIAMS CLARITY- ZEDD ROAR –KATY PERRY I NEED YOUR LOVE – ELLIE GOULDING WAKE ME UP – AVICCI RIGHT NOW – RIHANNA SAFE AND SOUND – CAPITAL CITIES ALIVE - KREWELLA GET LUCKY – DAFT PHARRELL I LOVE IT – ICONA POP I WILL WAIT – MUMFORD & SONS (RED ROCKS VERSION) HEY HO – THE LUMINEERS LITTLE TALKS – OF MONSTERS AND MEN DON OMAR – DANZA KUDARO FEEL THIS MOMENT – PITBULL FEAT. CHRISTINA AGUILERA DIAMONDS – RIHANNA STAY - RIHANNA HOME – PHILLIP PHILLIPS GONE – PHILLIP PHILLIPS DIE YOUNG – KESHA 1 GIRL ON FIRE –ALICIA KEYS DAYLIGHT – MAROON 5 LOVE SOMEBODY – MAROON 5 DRIVE BY- TRAIN THE A TEAM – ED SHEERAN LOCKED OUT OF HEAVEN – BRUNO MARS DON’T YOU WORRY CHILD – SWEEDISH HOUSE MAFIA SWEET NOTHING – CALVIN HARRIS/FLORENCE WELCH JUST GIVE ME A REASON – PINK FEAT. FUN CALL ME MAYBE – CARLY RAE JEPSEN GLAD YOU CAME – THE WANTED GOTYE – SOMEBODY THAT I USED TO KNOW TITANIUM – DAVID GUETTA & SIA WILD ONES – SIA/FLO-RIDA FEEL SO CLOSE – CALVIN HARRIS TURN ME ON – NIKKI MINAJ MR. SAXOBEAT – ALEXANDRA STAN GOOD LIFE – ONE REPUBLIC PITBULL/NE-YO – GIVE ME EVERYTHING SOMEONE LIKE YOU – ADELE MOVES LIKE JAGGER – MAROON 5 ONE MORE NIGHT – MAROON 5 DEV- DANCING IN THE DARK PUMPED UP KICKS – FOSTER THE PEOPLE -

Nashvillemusicguide.Com 1 “NAKED COWGIRL” $Andy Kane

NashvilleMusicGuide.com 1 “NAKED COWGIRL” $andy Kane Hit Single “I Love Nick” from NBC’s America’s Got Talent with Nick Cannon For Bookings & All Other Info Call 212.561.1838 -or- [email protected] NashvilleMusicGuide.com 2 NashvilleMusicGuide.com 1 writer From Getting Spins Letter from the Editor Contents Near and Far Publisher & CEO Randy Matthews 24 Yellow Ribbon Country Radio Seminar 2013 was a Speaking of songwriters, I met a really be surrounded by all the history. Read [email protected] Features huge success for the Nashville Music talented singer-songwriter during CRS up on our exclusive in this issue along Enhancement Guide. The feedback that we received this year. His name was Erik Dylan with many other great stories. Editor Amanda Andrews [email protected] was outstanding and we could not be and the first time I saw him, I had the Tin Pan South 25 Lisa Matassa more thankful for the approval of our opportunity to hear his song “Funerals Nashville Music Guide and Give A 4 Associate Editor Krys Midgett Better Late Than Never return to print. Be sure to check out our and Football Games” being performed Little Nashville would also like to [email protected] Songwriters Festival wrap up of CRS in this issue. on the Ryman stage. Check this song welcome some new team members to 26 Music, TV, & Film out if you have not heard it yet. Later our staff, Tyler Treft and June Johnson. Accounts Rhonda Smith April 2-6, 2013 We are still working out the kinks and on that same day, I had another great They will be aiding us in our sales and [email protected] Rockin the Rooster A Perfect Mix re-growing our business, so that being opportunity to hear Erik play in a more marketing department.