Island Words, Island Worlds: II

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hiiumaa 1 : 100

H I I U M A A 1 : 100 000 EESTI GEOLOOGILINE BAASKAART. RASKUSJÕUVÄLJA ANOMAALIAD GEOLOGICAL BASE MAP OF ESTONIA. GRAVITY ANOMALIES 5 0 5 0 5 0 5 0 5 0 5 0 5 0 8 9 9 0 0 1 1 2 2 3 3 4 4 5 22°0' 3 22°5' 3 22°10' 3 22°15' 4 22°20' 4 22°25' 4 22°30' 4 22°35' 4 22°40' 4 22°45' 4 22°50' 4 22°55' 4 23°0' 4 23°5' 4 23°10' LE GE N D 59°5' Lõimandi nina Isoanomaal -13,5 ,5 3 Isoanomal 6550 -13 5 6550 T a h k u-1n2, a 12 5 L e h t m a 59°5' - -11, -11 -10,5 Leh ,5 tm -9 a -10 j ,5 -8 5 , S -9 -7 ,5 u 14 11 8 5 2 -1 -4 -7 -10 -13 -16 mGal -6 u r M e e l s t e -8 ,5 j -5 ä M e e l s t e l a h t r -7 v -6 Kärrslätti neem K a u s t e VORMSI VARJUTATUD RELJEEF ("valgustatud" loodest) Kersli nina SHADED RELIEF ("lighting" from NW) 5 5 5 5 5 5 ORMSÖ 9 0 1 2 3 4 L Ä Ä N E M E R I 3 4 4 4 4 4 5 I 0, 6545 R Suursäär Kjulsnäs 6545 E (Kootsaare nina) M a n g u ,5 Kersleti jv -4 Tahkuna LKA M VORMSI Saxby neem E T a r e s t e l a h t Kjursskon K o d e s t e Tareste MKATõrvanina ORMSÖ -8 N ,5 M u d a s t e 6545 6545 Ä Kootsaare M a l v a s t e Ä poolsaar S i g a l a L T a r e s t e Vissulaid R i s t i 5,5 59°0' 6535 6535 2 Ninalaid R e i g i l a h t R e i g i R o o t s i K i d a s t e Vitberget K Ä R D L A 59°0' H a u s m a 5 , 6540 2 6540 K i r 6525 6525 i 5 5 k , , u ,5 2 4,5 5 5 l 2 5 Külalaid , a - 5, Paope LKA 5 h 6 Kadakalaid H - t P i h l a 5 , 4 Uuemererahu a P i l p a k ü l a 4 Elmrahu 5 4 Sääre nina - 6 Kukka laht r Kõrgessaare LKA K o i d m a Valgesäär i Västurvike KÕRGESSAARE 5 P a o p e l a h t T P , k (Västerviken) a ih 5 3 m l , K u k k a u 3 -

Lõputöö-Hookan-Lember.Pdf (2.127Mb)

Sisekaitseakadeemia Päästekolledž Hookan Lember RS150 PÄÄSTESÜNDMUSTE ANALÜÜS PÜSIASUSTUSEGA VÄIKESAARTEL Lõputöö Juhendaja: Häli Allas MA Kaasjuhendaja: Andres Mumma Tallinn 2018 ANNOTATSIOON Päästekolledž Kaitsmine: juuni 2018 Töö pealkiri eesti keeles: Päästesündmuste analüüs püsiasustusega väikesaartel Töö pealkiri võõrkeeles: The analysis of rescue events on small islands with permanent settlements Lühikokkuvõte: Töö on kirjutatud eesti keeles ning eesti ja inglise keelse kokkuvõttega. Töö koos lisadega on kirjutatud kokku 61 lehel, millest põhiosa on 38 lehekülge. Lõputöö koosneb kolmest peatükist, kus on kasutatud kahte tabelit ja seitseteist joonist. Valitud teema uurimisprobleemiks on tervikliku ülevaate puudumine väikesaarte sündmustest, mis kuuluvad Päästeameti valdkonda. Väikesaartele toimub reageerimine erinevalt ning sõltuvalt aastaajast on reageerimine raskendatud. Ühtseid põhimõtteid rahvaarvu või sündmuste arvu kohta ei ole. Lõputöö eesmärk on analüüsida päästesündmusi väikesaartel aastatel 2009-2017 ning järeldada, millist päästevõimekust vajavad püsiasutustega väikesaared. Lõputöös antakse saartest ülevaade, mis on valimis välja toodud ning visualiseeritakse joonise abil saartel elavate püsielanike arv. Eesmärgi saavutamiseks kasutati kvantitatiivset uurimismeetodit, kus Häirekeskuselt saadud andmed korrastati ja analüüsiti. Lõputöös anti ülevaade, millised on sündmused saartel ning tehti järeldused, kuidas tagada kiire ja kvaliteetse abi kättesaadavus. Saartel, kus elanike arv on väike ning sündmuste arv minimaalne, -

Island Hopping in Estonia: a Hiiumaa, Saaremaa and Muhu Padise Tallinn Kardla Baltic Se Hiiumaa Haapsalu

SELF-GUIDED Etonia FINLAND Helsinki Island Hopping in Estonia: a Hiiumaa, Saaremaa and Muhu Padise Tallinn Kardla Baltic Se Hiiumaa Haapsalu ain/Bus Koguva Varbla Tr ESTONIA Leisi Pärnu Saaremaa Kuressaare LATVIA Tour distances: cycling ~480 km/300 mi, ferry 44 km, 12 days/11 nights TOUR INFORMATION Cycling grade: We grade this trip as easy to moder- ate. Daily signposted biking routes, mainly on roads with little traffic and cycle paths in towns. The terrain 12-days self guided cycling tour from/to Tallinn (Code: SG9P) is varied and rolling with some gradual hills on some cycling days between Tallinn and Padise. 3 ferries be- Estonia is characterised by its unique natural landscapes and traditional hospitality. Vibrant cities, tween the Estonian islands are planned on this tour desert beaches, peace and the unspoiled beauty of the countryside - a paradise for cyclists. But it’s the (pay locally). Estonian islands which are the jewels of the country. You’ll spend your holiday on these islands which Arrival & departure information / Transfers are amongst the most beautiful that the Baltic Sea has to offer. Lighthouses and windmills are the land- Airport: Tallinn (www.tallinn-airport.ee) marks of these islands. To begin your journey, you will get to know the Estonian capital Tallinn. This tour Ferry terminal: Tallinn (regular ferry lines from Hel- then takes you from Haapsalu to the second largest island Hiiumaa before crossing to the biggest island, sinki (FI) & Stockholm (SE)) Saaremaa. En route back to the mainland, you’ll cycle on the island of Muhu & from there into the sum- Transfer: (price for one way for up to 3 people) mer capital of Estonia, Pärnu. -

Hiiumaa Valla Beebid Kohtusid Suuremõisas

Sündisid uued vallakodanikud ELEANOR METSKÜLA ANDREAS VÕSA JOHANNES ARU Õnnitleme vanemaid! Juuni 2019, nr 18 Hiiumaa valla beebid kohtusid Suuremõisas FFoto:oto: AArgorgo NNursurs 10. mail kogunesid 30 pisikest tööspetsialistide meisterdatud vallakodanikku koos peredega kaardi. Sama kujundusega oli ka Suuremõisa Lossi, et tähistada pidupäevaks küpsetatud Hiiumaa Hiiumaa aasta ema 2019 on Ly Klee Hiiumaa valla beebipäeva. Köök ja Pagari tort. Külalised Ehkki kõik kutsutud väikelapsed kiitsid nii torti kui suupistelauda, Meie tänavuse aasta ema väga hinnatud spetsialist oma ei saanud tulla, oli kohal hulga mille kattis Aimar Hansen. peres kasvab viis last, kel- täpsuse ja töökuse poolest. Ette- emasid ja isasid, õdesid ja vendi Hiljem said kõik pered soovi kor- lest kaks on kasulapsed, paneku tegija on teda kirjeldanud ning terve lossisaal oli rahvast ral lasta fotograaf Argo Nursil aga armastust jagub neile kui tugevat ja hoolivat ema, kes täis. end pildile jäädvustada ja ühispilt vajadusel julgeb seista nii enda kõikidele ühtemoodi. kui ka teiste laste eest. Olles Väiksemaid ja suuremaid val- tehti lossitrepile. ühiskondlikult aktiivne ja samas lakodanikke tervitas Emmaste Palju sära ja rõõmu kõikidele uute Selle pere lapsed on kõik väga luua soe ning armastav kodu oma osavalla sotsiaaltööspetsialist vallakodanikele ning nende pere- tublid ja hakkajad ning kahel on abikaasale ning viiele lapsele on Liia Rull, kelle sõnavõtule järgnes dele ja toredate kohtumisteni! jalge all juba ülikoolitee. Ema märkimisväärne oskus! Külli Kreegi juhendamisel tore suutnud säilitada positiivse el- muusikaline ülesaste Suuremõisa lusuhtumise ning olla olemas Palju õnne, armas Ly! lasteaed-põhikooli õpilastelt. Liia kõikide laste jaoks, luues neile Aasta ema kuulutati välja reedel, luges vahva luuletuse, saatjaks koos abikaasaga toetav ja ühte- 10. -

V Ä I N a M E

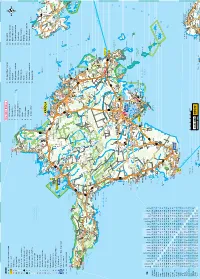

LEGEND Ring ümber Hiiumaa 9. Hiiumaa Militaarmuuseum 19. Kuriste kirik Turismiinfokeskus; turismiinfopunkt 1. Põlise leppe kivid 10. Mihkli talumuuseum 20. Elamuskeskus Tuuletorn Sadam; lennujaam Tahkuna nina Tahkuna 2. Pühalepa kirik 11. Reigi kirik 21. Käina kiriku varemed Haigla; apteek looduskaitseala 14 3. Suuremõisa loss 12. Kõrgessaare – Viskoosa 22. Orjaku linnuvaatlustorn Kirik; õigeusukirik Tahkuna 4. Soera talumuuseum ja Mõis; kalmistu 13. Kõpu tuletorn 23. Orjaku sadam kivimitemaja Huvitav hoone; linnuse varemed 14. Ristna tuletorn 24. Kassari muuseum 5. Kärdla Mälestusmärk: sündmusele; isikule 15. Kalana 25. Sääretirp Tahkuna ps Lehtma 6. Kärdla sadam Skulptuur; arheoloogiline paik Meelste Suurjärv 16. Vanajõe org 26. Kassari kabel ja kabeliaed 7. Ristimägi RMK külastuskeskus; allikas 14 17. Sõru sadam ja muuseum 27. Vaemla villavabrik Kauste 8. Tahkuna tuletorn Austurgrunne Pinnavorm; looduslik huviväärsus 18. Emmaste kirik Meelste laht Park; üksik huvitav puu Hiiu madal 50 Tjuka (Näkimadalad) Suursäär Tõrvanina R Rändrahn; ilus vaade Kodeste ä l Mangu Kersleti b (Kärrslätt) y Metsaonn; lõkkekoht 82 l Malvaste a 50 Ta Tareste mka Kakralaid Borrby h 50 Mudaste res t Karavaniparkla; telkimiskoht te Ogandi o Kootsaare ps Matkarada; vaatetorn Sigala Saxby Tareste KÄRDLA Diby Vissulaid 50 Vormsi Tuulik; tuugen Fällarna Reigi laht Risti 80 välijõusaal Rälby Reigi Roograhu H Kroogi Hausma 50 Tuletorn; mobiilimast Ninalaid Posti Rootsi Kidaste Huitberg 50 Muuseum; kaitserajatis Ninaots a Kanapeeksi Heilu Förby 13 Linnumäe Suuremõisa -

Woodworking in Estonia

WOODWORKING IN ESTONIA HISTORICAL SURVEY By Ants Viires Translated from Estonian by Mart Aru Published by Lost Art Press LLC in 2016 26 Greenbriar Ave., Fort Mitchell, KY 41017, USA Web: http://lostartpress.com Title: Woodworking in Estonia: Historical Survey Author: Ants Viires (1918-2015) Translator: Mart Aru Publisher: Christopher Schwarz Editor: Peter Follansbee Copy Editor: Megan Fitzpatrick Designer: Meghan Bates Index: Suzanne Ellison Distribution: John Hoffman Text and images are copyright © 2016 by Ants Viires (and his estate) ISBN: 978-0-9906230-9-0 First printing of this translated edition. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systems without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. This book was printed and bound in the United States. CONTENTS Introduction to the English Language Edition vii The Twisting Translation Tale ix Foreword to the Second Edition 1 INTRODUCTION 1. Literature, Materials & Methods 2 2. The Role Played by Woodwork in the Peasants’ Life 5 WOODWORK TECHNOLOGY 1. Timber 10 2. The Principal Tools 19 3. Processing Logs. Hollowing Work and Sealed Containers 81 4. Board Containers 96 5. Objects Made by Bending 127 6. Other Bending Work. Building Vehicles 148 7. The Production of Shingles and Other Small Objects 175 8. Turnery 186 9. Furniture Making and Other Carpentry Work 201 DIVISION OF LABOR IN THE VILLAGE 1. The Village Craftsman 215 2. Home Industry 234 FINAL CONCLUSIONS 283 Index 287 INTRODUCTION TO THE ENGLISH-LANGUAGE EDITION feel like Captain Pike. -

Seaweed Resources of the Baltic Sea, Kattegat and German and Danish

Botanica Marina 2020; 63(1): 61–72 Review Florian Weinberger*, Tiina Paalme and Sofia A. Wikström Seaweed resources of the Baltic Sea, Kattegat and German and Danish North Sea coasts https://doi.org/10.1515/bot-2019-0019 Received 30 March, 2019; accepted 8 October, 2019; online first 12 Introduction November, 2019 This publication provides an update to an earlier article by Abstract: Due to low salinity and lack of hard substrata, Schramm (1998), who already gave a detailed description the Baltic Sea and Kattegat area and German and Dan- of the macroalgal species distribution and diversity along ish North Sea coasts are characterized by a relatively SE North Sea and Baltic Sea coasts. During the last two low diversity of seaweeds. At the same time the areas decades several species introductions into the region have are severely eutrophicated, which has caused extensive been recorded [for example, approximately 10 on German shifts in macroalgal communities toward opportunistic coasts (Lackschewitz et al. 2014, Steinhagen et al. 2018)] species. Unattached seaweed communities dominated and also range shifts of species were observed within the by Furcellaria lumbricalis, which have been a resource area (Kovtun et al. 2009, Steinhagen et al. 2018). None- for hydrocolloid production since the 1940s, have been theless, the general distribution patterns outlined by severely reduced due to eutrophication and unsustain- Schramm (1998) still remain valid. At the German and able harvesting and are nowadays only exploited com- Danish West coasts, natural hard substratum that would mercially in Estonia. On the other hand, the biomass of allow for algal settlement is extremely rare and is almost opportunistic seaweeds of various red, green and brown only available around the German island of Helgoland, algal genera has increased. -

Kärdla, Mida Vahel Kutsutakse Hellitavalt Ka Pealin- M [email protected] Naks

Hiiumaa saar koos laidudega kuulub UNESCO biosfäärialade nimestikku. Kestva arengu eelkäijana, keskendub programm Man and Biosphere bio- E loogilise mitmekesisuse ja inimkultuuri tasakaalustatud koosarengusse elukeskkonna säästva majandamise põhimõtteid järgides. Meie väärtus- tame oma unikaalset loodust ja loodame, et ka saare külastajad käituvad vastutustundlikult. & www.hiiumaa.ee Saare keskuseks on Kärdla, mida vahel kutsutakse hellitavalt ka pealin- M [email protected] naks. Juba 14. sajandil paiknes siin väike rootslaste küla, mis hiljem arenes £ (+372) 504 5393 tööstuskeskuseks. Omaaegsetest asukatest annavad märku rootsi päritolu P Hiiu 1 (Keskväljakul), HIIUMAA koha- ning perekonnanimed. Oleme kaardile märkinud ca 5,3 km pikkuse tuuri Kärdla vaatamis- 92413, Kärdla, Hiiumaa TURISMIKAART väärsustest, mille läbimine jalutades võtab aega ca 1-1,5 h. #VisitHiiumaa Legend Kaitseala piir 1 Kärdla tuuri marsruut ja objektid TRANSPORDIINFO Turismiinfokeskus; inva-tualett; tualett Rattamarsruudid: Arstiabi; apteek; politsei Eurovelo marsruut 1 Kärdla KÄRDLA sadam Sadam; slipikoht; navigatsioonimärk marsruut 304 KORK marsruut 305 Kuur Vallavalitsus; bussijaam; raamatukogu 5 Sadama ait Kool; lasteaed; mänguväljak Titekivi S a Tareste laht d Spordirajatis; seikluspark; matkarada Kärdla rand a m 6 Lu b Kultuurimaja; teater; muuseum Rannapaargu ja a Hausma supluskoht rannavõrkpalli- ah väljakud ju Hausma tee Kirik; laululava; muu huvitav hoone N Ööbiku- p õi u park k Mälestusmärk; rändrahn; rand u Rannapark Väike-Sadama L t välijõusaal -

Coastal Meadow Management

coastal meadow management Best Practice Guidelines The experiences of LIFE-Nature project “Boreal Baltic Coastal Meadow Preservation in Estonia” LIFE00NAT/EE/7083 coastal meadow management Best Practice Guidelines MATSALU ESTONIAN MINISTRY DANCEE NATIONAL PARK OF ENVIRONMENT The experiences of LIFE-Nature project “Boreal Baltic Coastal Meadow Preservation in Estonia” LIFE00NAT/EE/7083 Compiled by Riinu Rannap, Lars Briggs, Kaja Lotman, Ilona Lepik, Voldemar Rannap Translated by Pirkko Põdra Photos Arne Ader, Lars Briggs, Fred Jüssi, Tiit Kaljuste, Mati Kose, Ilona Lepik, Kaja Lotman, Riinu Rannap, Voldemar Rannap, Merike Tamm, Ülle Tamm Drawings Elen Apsalon Layout Eerik Keerend This book has been printed on CyclusPrint recycled paper Ministry of the Environment of the Republic of Estonia Tallinn 2004 ISBN 9985-881-26-5 LIFE-Nature Project By way of introduction. Riinu Rannap, Voldemar Rannap 4 content Management Coastal meadow as a habitat. Kaja Lotman, Ilona Lepik 8 Amphibians • birds • plants Boreal Baltic coastal meadow management for Bufo calamita. Riinu Rannap 26 Restoration of breeding sites for threatened toads on coastal meadows. Lars Briggs 34 Suitable habitat management for Danish bird populations. Ole Thorup 44 Changes of bird communities in relation to management of coastal meadows in Estonia. Andres Kuresoo, Eve Mägi 52 Coastal meadow management from a botanist’s point of view. Tiit Kaljuste 62 Monitoring the Wild gladiolus (Gladiolus imbricatus) population under different meadow management regimes. Marika Kose, Mari Moora 70 Experiences The socio-economic aspect of coastal meadow management: the Matsalu example. Kaja Lotman 72 Managing meadows or managing people? Coastal meadow restoration and management in the Häädemeeste region. -

On How Crowdsourced Data and Landscape Organisation

Land 2020, 9, 158; doi:10.3390/land9050158 S1 of S6 Supplementary Materials: On How Crowdsourced Data and Landscape Organisation Metrics Can Facilitate the Mapping of Cultural Ecosystem Services: An Estonian Case Study, Land 2020, 9, Article No. Oleksandr Karasov, Stien Heremans, Mart Külvik, Artem Domnich and Igor Chervanyov Table S1. Number of cultural ecosystem service––CES-related photographs per protected area. Number of CES-related Name Description photos Lahemaa Rahvuspark National Park 738 Vainameri Baltic Sea Protected Area (HELCOM) 340 Otepaa Looduspark Protected Landscape (Nature Park) 319 Soomaa Rahvuspark National Park 188 Haanja Looduspark Protected Landscape (Nature Park) 159 Pohja-Korvemaa Looduskaitseala Nature Reserve 159 Kaina Lahe-Kassari Protected Landscape (Nature Park) 137 Maastikukaitseala Oru Pargi Maastikukaitseala Protected Landscape (Nature Park) 136 Site of Community Importance (Habitats Turisalu 131 Directive) Korvemaa Maastikukaitseala Protected Landscape (Nature Park) 125 Luitemaa Looduskaitseala Nature Reserve 121 Vortsjarve Special Protection Area (Birds Directive) 114 Tudusoo Looduskaitseala Nature Reserve 110 Varesemagede Maastikukaitseala Protected Landscape (Nature Park) 105 Piusa Joe Urgoru Maastikukaitseala Protected Landscape (Nature Park) 89 Viljandi Maastikukaitseala Protected Landscape (Nature Park) 83 Ontika Maastikukaitseala Protected Landscape (Nature Park) 77 Alutaguse rahvuspark National park 76 Ropka-Ihaste Looduskaitseala Nature Reserve 75 Ahja Joe Urgoru Maastikukaitseala Protected Landscape -

Liikmed 08.07.2019

NIMI ISIK SAAR ESINDAJA E-POST TELEFON Rein Lember eraisik Abruka [email protected] Abruka, Vahase, Saaremaa vald KOV Vilsandi, Kõinastu, Saaremaa Jätkusuutlik Aegna MTÜ Aegna Hugo Udusaar [email protected] Kaido Taberland eraisik Heinlaid ja Naissaar [email protected] Hiiumaa vald KOV Hiiumaa, Kassari Riho Rahuoja Kassari Haridusselts MTÜ Kassari Linda Tikk [email protected] Külli Laos eraisik Kihnu [email protected] Egon Vohu eraisik Kihnu [email protected] Jüri Lember eraisik Kõinastu [email protected] Manõja Kultuuriselts MTÜ Manõja Svea Aavik [email protected] Mark Soosaar eraisik Manõja [email protected] Pärnu linn KOV Manõja Svea Aavik eraisik Manõja [email protected] Muhu vald KOV Muhu, Kesselaid Meelis Mereäär [email protected] Naissaarlaste Kogukond MTÜ Naissaar Toomas Luhaäär [email protected] Patrik Göransson eraisik Naissaar [email protected] Tõnu Kaljuste eraisik Naissaar [email protected] Viimsi vald KOV Naissaar, Prangli Terje Lilleoks [email protected] Lääne-Nigula vald KOV Osmussaar Osmussaare Fond SA Osmussaar Rita Koppel [email protected] Pakri Saarte Kogukond MTÜ Pakri Jana Stahl [email protected] Juhan Bernadt eraisik Pakri [email protected] Pakri Kultuuripärand MTÜ Pakri Jana Stahl [email protected] Lääne-Harju vald KOV Pakri Tartu vald KOV Piirissaar Valentina Aman Piirissaare Kultuuriselts MTÜ Piirissaar Siim Avi [email protected] Prangli Saarte Selts MTÜ Prangli Vambola Kahro [email protected] Prangli Saare Külade Selts MTÜ Prangli Terje Lilleoks [email protected] -

Kormorani Levik Ja Arvukus Eestis

FIE Vilju Lilleleht Töövõtulepingu nr 2-24/Trt-11, 25. märts 2008 aruanne KORMORANI LEVIK JA ARVUKUS EESTIS Vilju Lilleleht Tellija: Metsakaitse- ja Metsauuenduskeskus Tartu 2008 Sisukord Sissejuhatus.......................................................................................................................................... 4 Eesmärgid ............................................................................................................................................. 5 1. Materjal ja metoodika ........................................................................................................................ 6 2. Kormorani levik ja arvukus Eestis 2008. a. ....................................................................................... 7 2.1. Kormorani pesitsuskolooniate hulk ja paiknemine ..................................................................... 7 2.2. Kormorani arvukus erinevates kolooniates ................................................................................ 8 2.2.1. Soome laht .......................................................................................................................... 8 2.2.1.1. Lõuna-Uhtju (Sala) .................................................................................................... 8 2.2.1.2.. Põhja-Uhtju (Uhtju) ................................................................................................... 8 2.2.1.3. Eru Suurlood (Kasispea Suurlood) ........................................................................... 8 2.2.1.4.