The Sikhs of the Punjab Revised Edition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Causes of the First Anglo-Afghan War

wbhr 1|2012 The Causes of the First Anglo-Afghan War JIŘÍ KÁRNÍK Afghanistan is a beautiful, but savage and hostile country. There are no resources, no huge market for selling goods and the inhabitants are poor. So the obvious question is: Why did this country become a tar- get of aggression of the biggest powers in the world? I would like to an- swer this question at least in the first case, when Great Britain invaded Afghanistan in 1839. This year is important; it started the line of con- flicts, which affected Afghanistan in the 19th and 20th century and as we can see now, American soldiers are still in Afghanistan, the conflicts have not yet ended. The history of Afghanistan as an independent country starts in the middle of the 18th century. The first and for a long time the last man, who united the biggest centres of power in Afghanistan (Kandahar, Herat and Kabul) was the commander of Afghan cavalrymen in the Persian Army, Ahmad Shah Durrani. He took advantage of the struggle of suc- cession after the death of Nāder Shāh Afshār, and until 1750, he ruled over all of Afghanistan.1 His power depended on the money he could give to not so loyal chieftains of many Afghan tribes, which he gained through aggression toward India and Persia. After his death, the power of the house of Durrani started to decrease. His heirs were not able to keep the power without raids into other countries. In addition the ruler usually had wives from all of the important tribes, so after the death of the Shah, there were always bloody fights of succession. -

Download Thesis

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ Imagining Afghanistan British Foreign Policy and the Afghan Polity, 18081878 Bayly, Martin Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 25. Sep. 2021 This electronic theses or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ Title: Imagining Afghanistan: British Foreign Policy and the Afghan Polity, 1808‐1878 Author: Martin Bayly The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. -

FOREWORD the Need to Prepare a Clear and Comprehensive Document

FOREWORD The need to prepare a clear and comprehensive document on the Punjab problem has been felt by the Sikh community for a very long time. With the release of this White Paper, the S.G.P.C. has fulfilled this long-felt need of the community. It takes cognisance of all aspects of the problem-historical, socio-economic, political and ideological. The approach of the Indian Government has been too partisan and negative to take into account a complete perspective of the multidimensional problem. The government White Paper focusses only on the law and order aspect, deliberately ignoring a careful examination of the issues and processes that have compounded the problem. The state, with its aggressive publicity organs, has often, tried to conceal the basic facts and withhold the genocide of the Sikhs conducted in Punjab in the name of restoring peace. Operation Black Out, conducted in full collaboration with the media, has often led to the circulation of one-sided versions of the problem, adding to the poignancy of the plight of the Sikhs. Record has to be put straight for people and posterity. But it requires volumes to make a full disclosure of the long history of betrayal, discrimination, political trickery, murky intrigues, phoney negotiations and repression which has led to blood and tears, trauma and torture for the Sikhs over the past five decades. Moreover, it is not possible to gather full information, without access to government records. This document has been prepared on the basis of available evidence to awaken the voices of all those who love justice to the understanding of the Sikh point of view. -

The History of Punjab Is Replete with Its Political Parties Entering Into Mergers, Post-Election Coalitions and Pre-Election Alliances

COALITION POLITICS IN PUNJAB* PRAMOD KUMAR The history of Punjab is replete with its political parties entering into mergers, post-election coalitions and pre-election alliances. Pre-election electoral alliances are a more recent phenomenon, occasional seat adjustments, notwithstanding. While the mergers have been with parties offering a competing support base (Congress and Akalis) the post-election coalition and pre-election alliance have been among parties drawing upon sectional interests. As such there have been two main groupings. One led by the Congress, partnered by the communists, and the other consisting of the Shiromani Akali Dal (SAD) and Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). The Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) has moulded itself to joining any grouping as per its needs. Fringe groups that sprout from time to time, position themselves vis-à-vis the main groups to play the spoiler’s role in the elections. These groups are formed around common minimum programmes which have been used mainly to defend the alliances rather than nurture the ideological basis. For instance, the BJP, in alliance with the Akali Dal, finds it difficult to make the Anti-Terrorist Act, POTA, a main election issue, since the Akalis had been at the receiving end of state repression in the early ‘90s. The Akalis, in alliance with the BJP, cannot revive their anti-Centre political plank. And the Congress finds it difficult to talk about economic liberalisation, as it has to take into account the sensitivities of its main ally, the CPI, which has campaigned against the WTO regime. The implications of this situation can be better understood by recalling the politics that has led to these alliances. -

The Battle of Sobraon*

B.A. 1ST YEAR IIND SEMESTER Topic : *The Battle of Sobraon* The Battle of Sobraon was fought on 10 February 1846, between the forces of the East India Company and the Sikh Khalsa Army, the army of the Sikh Empire of the Punjab. The Sikhs were completely defeated, making this the decisive battle of the First Anglo-Sikh War. The First Anglo-Sikh war began in late 1845, after a combination of increasing disorder in the Sikh empire following the death of Ranjit Singh in 1839 and provocations by the British East India Company led to the Sikh Khalsa Army invading British territory. The British had won the first two major battles of the war through a combination of luck, the steadfastness of British and Bengal units and equivocal conduct bordering on deliberate treachery by Tej Singh and Lal Singh, the commanders of the Sikh Army. On the British side, the Governor General, Sir Henry Hardinge, had been dismayed by the head-on tactics of the Bengal Army's commander-in-chief, Sir Hugh Gough, and was seeking to have him removed from command. However, no commander senior enough to supersede Gough could arrive from England for several months. Then the army's spirits were revived by the victory gained by Sir Harry Smith at the Battle of Aliwal, in which he eliminated a threat to the army's lines of communication, and the arrival of reinforcements including much-needed heavy artillery and two battalions of Gurkhas. The Sikhs had been temporarily dismayed by their defeat at the Battle of Ferozeshah, and had withdrawn most of their forces across the Sutlej River. -

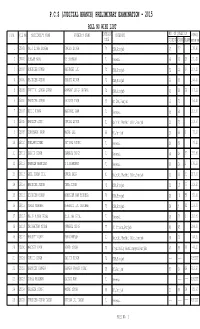

P.C.S (Judicial Branch) Preliminary Examination - 2015 Roll No Wise List S.No

P.C.S (JUDICIAL BRANCH) PRELIMINARY EXAMINATION - 2015 ROLL NO WISE LIST S.NO. ROLL NO CANDIDATE'S NAME FATHER'S NAME CATEGORY CATEGORY NO. OF QUESTION MARKS CODE CORRECT WRONG BLANK (OUT OF 500) 1 25001 NAIB SINGH SANGHA GURDEV SINGH 72 ESM,Punjab 48 77 130.40 2 25002 NEELAM RANI OM PARKASH 71 General 45 61 19 131.20 3 25003 AMNINDER KUMAR KASHMIRI LAL 72 ESM,Punjab 32 26 67 107.20 4 25004 RAJINDER SINGH SANGAT SINGH 72 ESM,Punjab 56 69 168.80 5 25005 PREETPAL SINGH GREWAL HARWANT SINGH GREWAL 72 ESM,Punjab 41 58 26 117.60 6 25006 NARENDER SINGH DAULATS INGH 86 BC ESM,Punjab 53 72 154.40 7 25007 RISHI KUMAR MANPHOOL RAM 71 General 65 60 212.00 8 25008 HARDEEP SINGH GURDAS SINGH 81 Balmiki/Mazhbi Sikh,Punjab 52 73 149.60 9 25009 GURCHARAN KAUR MADAN LAL 85 BC,Punjab 36 88 1 73.60 10 25010 NEELAMUSONDHI SAT PAL SONDHI 71 General 29 96 39.20 11 25011 DALVIR SINGH KARNAIL SINGH 71 General 44 24 57 156.80 12 25012 KARMESH BHARDWAJ S L BHARDWAJ 71 General 99 24 2 376.80 13 25013 ANIL KUMAR GILL DURGA DASS 81 Balmiki/Mazhbi Sikh,Punjab 61 33 31 217.60 14 25014 MANINDER SINGH TARA SINGH 72 ESM,Punjab 31 19 75 108.80 15 25015 DEVINDER KUMAR MOHINDER RAM BHUMBLA 72 ESM,Punjab 25 10 90 92.00 16 25016 VIKAS GIRDHAR KHARAITI LAL GIRDHAR 72 ESM,Punjab 34 9 82 128.80 17 25017 RAJIV KUMAR GOYAL BHIM RAJ GOYAL 71 General 45 79 1 116.80 18 25018 NACHHATTAR SINGH GURMAIL SINGH 77 SC Others,Punjab 80 45 284.00 19 25019 HARJEET KUMAR RAM PARKASH 81 Balmiki/Mazhbi Sikh,Punjab 55 70 164.00 20 25020 MANDEEP KAUR AJMER SINGH 76 Physically Handicapped,Punjab 47 59 19 140.80 21 25021 GURDIP SINGH JAGJIT SINGH 72 ESM,Punjab --- --- --- ABSENT 22 25022 HARPREET KANWAR KANWAR JAGBIR SINGH 85 BC,Punjab 83 24 18 312.80 23 25023 GOPAL KRISHAN DAULAT RAM 71 General --- --- --- ABSENT 24 25024 JAGSEER SINGH MODAN SINGH 85 BC,Punjab 33 58 34 85.60 25 25025 SURENDER SINGH TAXAK ROSHAN LAL TAXAK 71 General --- --- --- ABSENT PAGE NO. -

Muslim Saints of South Asia

MUSLIM SAINTS OF SOUTH ASIA This book studies the veneration practices and rituals of the Muslim saints. It outlines the principle trends of the main Sufi orders in India, the profiles and teachings of the famous and less well-known saints, and the development of pilgrimage to their tombs in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh. A detailed discussion of the interaction of the Hindu mystic tradition and Sufism shows the polarity between the rigidity of the orthodox and the flexibility of the popular Islam in South Asia. Treating the cult of saints as a universal and all pervading phenomenon embracing the life of the region in all its aspects, the analysis includes politics, social and family life, interpersonal relations, gender problems and national psyche. The author uses a multidimen- sional approach to the subject: a historical, religious and literary analysis of sources is combined with an anthropological study of the rites and rituals of the veneration of the shrines and the description of the architecture of the tombs. Anna Suvorova is Head of Department of Asian Literatures at the Institute of Oriental Studies, Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow. A recognized scholar in the field of Indo-Islamic culture and liter- ature, she frequently lectures at universities all over the world. She is the author of several books in Russian and English including The Poetics of Urdu Dastaan; The Sources of the New Indian Drama; The Quest for Theatre: the twentieth century drama in India and Pakistan; Nostalgia for Lucknow and Masnawi: a study of Urdu romance. She has also translated several books on pre-modern Urdu prose into Russian. -

The Sikh Prayer)

Acknowledgements My sincere thanks to: Professor Emeritus Dr. Darshan Singh and Prof Parkash Kaur (Chandigarh), S. Gurvinder Singh Shampura (member S.G.P.C.), Mrs Panninder Kaur Sandhu (nee Pammy Sidhu), Dr Gurnam Singh (p.U. Patiala), S. Bhag Singh Ankhi (Chief Khalsa Diwan, Amritsar), Dr. Gurbachan Singh Bachan, Jathedar Principal Dalbir Singh Sattowal (Ghuman), S. Dilbir Singh and S. Awtar Singh (Sikh Forum, Kolkata), S. Ravinder Singh Khalsa Mohali, Jathedar Jasbinder Singh Dubai (Bhai Lalo Foundation), S. Hardarshan Singh Mejie (H.S.Mejie), S. Jaswant Singh Mann (Former President AISSF), S. Gurinderpal Singh Dhanaula (Miri-Piri Da! & Amritsar Akali Dal), S. Satnam Singh Paonta Sahib and Sarbjit Singh Ghuman (Dal Khalsa), S. Amllljit Singh Dhawan, Dr Kulwinder Singh Bajwa (p.U. Patiala), Khoji Kafir (Canada), Jathedar Amllljit Singh Chandi (Uttrancbal), Jathedar Kamaljit Singh Kundal (Sikh missionary), Jathedar Pritam Singh Matwani (Sikh missionary), Dr Amllljit Kaur Ibben Kalan, Ms Jagmohan Kaur Bassi Pathanan, Ms Gurdeep Kaur Deepi, Ms. Sarbjit Kaur. S. Surjeet Singh Chhadauri (Belgium), S Kulwinder Singh (Spain), S, Nachhatar Singh Bains (Norway), S Bhupinder Singh (Holland), S. Jageer Singh Hamdard (Birmingham), Mrs Balwinder Kaur Chahal (Sourball), S. Gurinder Singh Sacha, S.Arvinder Singh Khalsa and S. Inder Singh Jammu Mayor (ali from south-east London), S.Tejinder Singh Hounslow, S Ravinder Singh Kundra (BBC), S Jameet Singh, S Jawinder Singh, Satchit Singh, Jasbir Singh Ikkolaha and Mohinder Singh (all from Bristol), Pritam Singh 'Lala' Hounslow (all from England). Dr Awatar Singh Sekhon, S. Joginder Singh (Winnipeg, Canada), S. Balkaran Singh, S. Raghbir Singh Samagh, S. Manjit Singh Mangat, S. -

Ethnographic Series, Part-V-B, Vol-XIII, Punjab

CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 Y·OLUMB xm. PART V-B PUNJAB (ETHNOGRAPIlIC ~ERIE's) (BATWAL; BHAN.JRA; DU.VINAJ MAHA,SHA OR DOOM; ~AGRA; qANDHILA OR GANnIL GONDOLA; ~ARERA; DEHA, DHAYA OR DHEA). P.;L. SONDHI.. DIRECTOR OF CENSUS OPERATIONS AND EX O:FFICTO SUPERINTENDENT OF CENSUS OPERAT~ONS, PUNJAB. SUMMARY 01' CONTENTS Pages Foreword v Preface vii-x 1. Batwal 1-13 II. Bhanjra 19-29 Ill. Dumna, Mahasha or Doom 35-49 IV. Gagra 55-61 V. GandhUa or GandH Gondo1a 67-77 VI. Sarera 83-93 VII. Deha, Dhaya or Dhea .. 99-109 ANNEXURE: Framework for ethnographic study .. 111-115 }1~OREWORD The Indian Census has had the privIlege of presenting authentic ethnographic accounts of Indian communities. It was usual in all censuses to collect and publish information on race, tribes and castes. The Constitution lays down that "the state shall promote with special care educational and economic interests of the weaker sections of the people and, in parti cular, of the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes and shall protect them from social injustice and all forms of exploitation". To assist states in fulfiHing their responsibility in this regard the 1961 Census provided a series of special tabulations of the social and economic data on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes. The lists of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes are notified by the Presi· dent under the Constitution and the Parliament is empowered to include or exclude from the lists any caste or tribe. No other source can claim the same authenticity and comprehensiveness as the census of India to help the Government in taking de· cisions on matters such as these. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD— Extensions of Remarks E1674 HON

E1674 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks August 1, 2007 INTRODUCTION OF THE UNI- Because of decades of refusal by Congress He has managed several successful local VERSAL PRE-KINDERGARTEN to approve the large sums necessary for uni- and State political campaigns. Mr. Pugh AND EARLY CHILDHOOD EDU- versal health coverage, the Universal Pre-K served as chair of the Saginaw County Rev- CATION ACT OF 2007 Act encourages school districts across the erend Jesse Jackson for President Committee United States to apply to the Department of in 1984 and 1988. Rev. Jesse Jackson won in HON. ELEANOR HOLMES NORTON Education for grants to establish three and Saginaw County in 1984. In 1988, again under OF THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA four-year-old kindergartens. Grants funded Mr. Pugh’s leadership, Jackson won the Sagi- IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES under Title IV of the Elementary and Sec- naw district. Mr. Pugh served as a delegate to ondary Education Act, ESEA, would be avail- the National Democratic Convention in 1988 Tuesday, July 31, 2007 able to school systems which agree in turn to and 1992. Ms. NORTON. Madam Speaker, I am intro- use the experience acquired with the Federal His community involvement includes: found- ducing today the Universal Pre-kindergarten funding provided by my bill to then move for- ing board member of the Ruben Daniels Edu- and Early Childhood Education Act of 2007 ward, where possible, to phase in three and cational Foundation, member of Saginaw (Universal Pre-K) to begin the process of pro- four-year-old kindergartens for all children in County Mental Health Authority, chair of the viding universal, public school pre-kinder- the school district in regular classrooms with Saginaw Branch NAACP ACT–SO Program, garten education for every child, regardless of teachers equivalent to those in other grades member of Zion Missionary Baptist Church income. -

GOD's ACRE in NORTH-WEST INDIA. Ferozpur. THIS Cantonment Is Rich in Memorials of the Glorious Dead. in Fact, the Church" W

J R Army Med Corps: first published as 10.1136/jramc-23-04-04 on 1 October 1914. Downloaded from 415 GOD'S ACRE IN NORTH-WEST INDIA. By COLONEL R. H. FIRTH. (Continued from p. 333.) FERozPUR. THIS cantonment is rich in memorials of the glorious dead. In fact, the church" Was erected to the glory of God in memory of those who fell fighting for their country in this district during the Sutlej Campaign of 1845-1846," and contains many tablets of interest. In the old civil cemetery are graves of the following who especially interest us :- Assistant-Surgeon Robert Beresford Gahan entered the service on June] 7, 1836, and was sent at once to Mauritius. He returned home in ]840, and soon after was posted to the 9th Foot, then in India. Coming out he was unable to join his regiment as it was in Afghanistan, but did general duty in Cawnpur and Meerut, Protected by copyright. ultimately joining it at Sabathu in February, 1843. Towards the end of September, 1845, he was transferred to the 31st Foot,which he joined at Amballa and accompanied them into the field. He was mortally wounded at the battle of Mudki, whilst gallantly doing his professional duties under fire, and died eleven days later in Ferozpur, on December 29, 1845. His name is to be found also on a special monument to the 31st Foot in the cemetery, and on a memorial tablet in St. Andrew's Church. Lieutenant Augustus Satchwell J ohnstone was the son of Surgeon James Johnstone, of the Bengal Medical Service. -

![315 T/Ie Punjab Appropriation [ RAJYA SABHA ] (No](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4126/315-t-ie-punjab-appropriation-rajya-sabha-no-1754126.webp)

315 T/Ie Punjab Appropriation [ RAJYA SABHA ] (No

315 T/ie Punjab Appropriation [ RAJYA SABHA ] (No. 2) Bill, 1984 316 Punjab Apropriation (No. 2) Bill, 1984 has been placed before this House lor consideration indicates the state of affairs that is obtaining today in Punjab. Sir, you are aware that under article 356 of the Constitu!io;i, administration of the State of Punjab wns taken over by Ihe President of India, and as a consequence of that pro- clamation and Act made by the President of India, Parliament is benig asked to pass the Punjab Appropriation Bill. As we have seen, since 6th October, 1983, when the President's Rule was imposed in Punjab, the state of affairs which has developed in Punjab has become a national problem. The other day, my esteemed colleague Mr. Darbara Singh had rightly stated that the problem of Punjab was not a problem of Punjab alone; it was a national problem. Sir, in Punjab, when, the Slate administra- tion was taken over by the President of India, it was stated that in order to help overcome the impasse the State was under- going, the imposition of President's Rule was essential. So the State Government was dismissed, though the State Legislative Assembly was not dissolved. Naturally, it was taken for granted, when the State Government was dismissed that the State Government was not capable of handling the situation obtaining at that time. But. after that, we saw a new set of Govern- ors with a new set of advisers, the police directors, etc. All these people were com- missioned for handling the Punjab situa- tion.