Flight to Pakistan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'EMU' Nominated 'Global Cultural Ambassador' for Pakistan Souq

Wednesday, March 11, 2020 15 Reports by L N Mallick For events and press releases email [email protected] or L N Mallick Pakistan Prism L N Mallick call (974) 4000 2222 L N Mallick ‘EMU’ nominated ‘Global Cultural Ambassador’ for Pakistan Souq Syed Muhammad Imran Momina, alias ‘EMU’ of the legendary music band Fuzön, was awarded the ambassadorship at a ceremony attended by Pakistani community members, music enthusiasts, local singers and musicians YED Muhammad Imran Mo- mina, alias ‘EMU’ of the leg- endary music band Fuzön, was declared the Global Cultural Ambassador for Pakistan Souq Sin Doha recently. EMU visited Doha at the invitation of Pakistan Souq and was awarded the am- bassadorship in a ceremony attended by a large number of Pakistani community members, notables and influencers of the community, music enthusiasts, and local singers and musicians. Supported by Pakistan Embassy Qa- tar, Pakistan Souq is an online community platform created primarily for business purposes. It’s become very popular be- cause of its social, cultural and community- friendly activities. Its aim is to engage the Pakistani community in economic, social and cultural arenas. Syed Muhammad Imran Momina, alias EMU, poses EMU was accompanied by Pakistan Souq for picture in front of Tornado Tower in Doha. CEO Amir Saeed Khan to the event, which was graced by Pakistan Ambassador to Qatar HE Syed Ahsan Raza Shah and Commercial Secretary Salman Ali. The ambassador welcomed EMU in Doha and congratulated him on his nomination as Global Cultural Ambassador of music and showbiz for Pakistan Souq. Dr Khalil Ullah Shibli, who coordinated EMU’s Doha visit, said this honour is likely EMU with Pakistan Souq CEO Amir Saeed Khan (left) and Dr Khalil Ullah Shibli (right). -

12 Hours Opens Under Blue Skies and Yellow Flags

C M Y K INSPIRING Instead of loading up on candy, fill your kids’ baskets EASTER with gifts that inspire creativity and learning B1 Devils knock off county EWS UN s rivals back to back A9 NHighlands County’s Hometown Newspaper-S Since 1927 75¢ Cammie Lester to headline benefit Plan for spray field for Champion for Children A5 at AP airport raises a bit of a stink A3 www.newssun.com Sunday, March 16, 2014 Health A PERFECT DAY Dept. in LP to FOR A RACE be open To offer services every other Friday starting March 28 BY PHIL ATTINGER Staff Writer SEBRING — After meet- ing with school and coun- ty elected officials Thurs- day, Florida Department of Health staff said the Lake Placid office at 106 N, Main Ave. will be reopen- ing, but with a reduced schedule. Tom Moran, depart- ment spokesman, said in a Katara Simmons/News-Sun press release that the Flor- The Mobil 1 62nd Annual 12 Hours of Sebring gets off to a flawless start Saturday morning at Sebring International Raceway. ida Department of Health in Highlands County is continuing services at the Lake Placid office ev- 12 Hours opens under blue ery other Friday starting March 28. “The Department con- skies and yellow flags tinues to work closely with local partners to ensure BY BARRY FOSTER Final results online at Gurney Bend area of the health services are avail- News-Sun Correspondent www.newssun.com 3.74-mile course. Emergen- able to the people of High- cy workers had a tough time lands County. -

Free Companions.Xlsx

Free Companion List By AladdinAnon Key Type = There are 4 types Jump Name = Name of Jump Canon = Canon Charcter, typically a gift Folder = Which folder to find the jump OC = Get an OC Character, typically a "create your own" option Companion = What you get Scenario = required to do a scenario to get the companion Source = Copy and ctrl+F to find their location in jump doc Drawback = Taking the companion is optional after the drawback is finished TG Drive Jumps starting with Numbers Folder Companion Type Source 10 Billion Wives Gauntlets 0 - 10 Billion Wives OC 10 Billion Wives Jumps starting with A Folder Companion Type Source A Brother’s Price A-M Family OC Non Drop-ins A Brother’s Price A-M Husband OC Non Drop-in Women A Brother’s Price A-M Mentor OC Non Drop-in Men A Brother’s Price A-M Aged Spinsters OC Drop-ins of any Gender A Practical Guide to Evil A-M Rival Drawback Rival (+100) A Super Mario…Thing Images 1 OC OC Multiplayer Option After War Gundam X Gundum Frost brothers Drawback A Frosty Reception (+200cp/+300cp) Age of Empires III: Part 1: Blood Age of Empires III Pick 1 of 5 Canon Faction Alignment Ah! My Goddess A-M Goddess Waifu Scenario Child of Ash and Elm Ah! My Goddess A-M Raising Iðavöllr Scenario Iðavöllr AKB49 - Renai Kinshi Jourei (The Rules Against Love) A-M 1 A New Talent OC Drop-In, Fan, Stagework AKB49 - Renai Kinshi Jourei (The Rules Against Love) A-M 1 Canon Companion Canon Kenkyusei, Idol, Producer AKB49 - Renai Kinshi Jourei (The Rules Against Love) A-M Rival Drawback 0CP Rivals AKB49 - Renai Kinshi Jourei (The Rules Against Love) A-M Yoshinaga Drawback 400CP For Her Dreams Aladdin Disney Iago Canon Iago Aladdin Disney Mirage Scenario Mirage’s Wrath Aladdin Disney Forty Thieves Scenario Jumper And The Forty Thieves. -

Book Review Essay Siren Song

Journal of International Women's Studies Volume 21 Issue 6 Article 41 August 2020 Book Review Essay Siren Song Taimur Rahman Follow this and additional works at: https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws Part of the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Rahman, Taimur (2020). Book Review Essay Siren Song. Journal of International Women's Studies, 21(6), 516-519. Available at: https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol21/iss6/41 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. This journal and its contents may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. ©2020 Journal of International Women’s Studies. Siren Song1 Reviewed by Taimur Rahman2 The title of this book is extremely misleading. This is not a book about siren songs. Or perhaps it is, but not in the way you think. The book draws you in, dressed as a biography of prominent Pakistani female singers. And then, you find yourself trapped into a complex discussion of post-colonial philosophy stretching across time (in terms of philosophy) and space (in terms of continents). Hence, any review of this book cannot be a simple retelling of its contents but begs the reader to engage in some seriously strenuous thinking. I begin my review, therefore, not with what is in, but with what is not in the book - the debate that shapes the book, and to which this book is a stimulating response. -

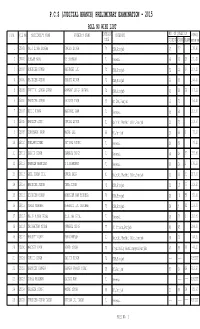

P.C.S (Judicial Branch) Preliminary Examination - 2015 Roll No Wise List S.No

P.C.S (JUDICIAL BRANCH) PRELIMINARY EXAMINATION - 2015 ROLL NO WISE LIST S.NO. ROLL NO CANDIDATE'S NAME FATHER'S NAME CATEGORY CATEGORY NO. OF QUESTION MARKS CODE CORRECT WRONG BLANK (OUT OF 500) 1 25001 NAIB SINGH SANGHA GURDEV SINGH 72 ESM,Punjab 48 77 130.40 2 25002 NEELAM RANI OM PARKASH 71 General 45 61 19 131.20 3 25003 AMNINDER KUMAR KASHMIRI LAL 72 ESM,Punjab 32 26 67 107.20 4 25004 RAJINDER SINGH SANGAT SINGH 72 ESM,Punjab 56 69 168.80 5 25005 PREETPAL SINGH GREWAL HARWANT SINGH GREWAL 72 ESM,Punjab 41 58 26 117.60 6 25006 NARENDER SINGH DAULATS INGH 86 BC ESM,Punjab 53 72 154.40 7 25007 RISHI KUMAR MANPHOOL RAM 71 General 65 60 212.00 8 25008 HARDEEP SINGH GURDAS SINGH 81 Balmiki/Mazhbi Sikh,Punjab 52 73 149.60 9 25009 GURCHARAN KAUR MADAN LAL 85 BC,Punjab 36 88 1 73.60 10 25010 NEELAMUSONDHI SAT PAL SONDHI 71 General 29 96 39.20 11 25011 DALVIR SINGH KARNAIL SINGH 71 General 44 24 57 156.80 12 25012 KARMESH BHARDWAJ S L BHARDWAJ 71 General 99 24 2 376.80 13 25013 ANIL KUMAR GILL DURGA DASS 81 Balmiki/Mazhbi Sikh,Punjab 61 33 31 217.60 14 25014 MANINDER SINGH TARA SINGH 72 ESM,Punjab 31 19 75 108.80 15 25015 DEVINDER KUMAR MOHINDER RAM BHUMBLA 72 ESM,Punjab 25 10 90 92.00 16 25016 VIKAS GIRDHAR KHARAITI LAL GIRDHAR 72 ESM,Punjab 34 9 82 128.80 17 25017 RAJIV KUMAR GOYAL BHIM RAJ GOYAL 71 General 45 79 1 116.80 18 25018 NACHHATTAR SINGH GURMAIL SINGH 77 SC Others,Punjab 80 45 284.00 19 25019 HARJEET KUMAR RAM PARKASH 81 Balmiki/Mazhbi Sikh,Punjab 55 70 164.00 20 25020 MANDEEP KAUR AJMER SINGH 76 Physically Handicapped,Punjab 47 59 19 140.80 21 25021 GURDIP SINGH JAGJIT SINGH 72 ESM,Punjab --- --- --- ABSENT 22 25022 HARPREET KANWAR KANWAR JAGBIR SINGH 85 BC,Punjab 83 24 18 312.80 23 25023 GOPAL KRISHAN DAULAT RAM 71 General --- --- --- ABSENT 24 25024 JAGSEER SINGH MODAN SINGH 85 BC,Punjab 33 58 34 85.60 25 25025 SURENDER SINGH TAXAK ROSHAN LAL TAXAK 71 General --- --- --- ABSENT PAGE NO. -

All Primary Book Final.FH10

Contents 01 Welcome to the IBA 02 Major Milestones in the Journey of Excellence Creating leaders who dare to 03 The Policy Makers envision and succeed 04 Dean & Directors Message 05 Our Core Values 06 Registrars Note 07 The Academia l Professors Emeritus l Message from the Associate Deans l Full-time Faculty l Visiting Faculty 21 Academic Departments 22 The Old & New 23 Facilities 27 Departmental Heads 28 Enhancing our Outreach Empowering and equipping 29 Alliances & Partnerships Managers & Executives to 30 Guest Book serve the nation even better 31 The IBA Student Council, Societies & Clubs 33 Evergreen-The IBA Alumni 34 Our Guests at the DLS 36 Convocation 2009 38 IBA Gallery 40 Overview of Programs 41 Programs of Study 43 Admission Policy & Procedures 47 Rules & Regulations 50 Evaluation & Grading 52 Financial Assistance 53 Endowment Funds The preferred choice of 54 Academic Calendar employers, both in private & 55 Tentative List of Holidays public sectors 56 Fee Structure 57 Our Contacts 59 The Karachi Edge 60 Direction Maps Encl: l Undergraduate Programs l Graduate Programs Welcome to the IBA A business school is known by the quality of its students, the professionalism of its faculty, the dedication and leadership of its management, and the value its alumni add to society. In the global village, a business school has to maintain the highest standards of excellence, inculcate strong ethical values and encourage inquisitiveness and lifelong learning. IBA, the oldest business school outside North America, was established in 1955 with the collaboration of Wharton School of Finance, University of Pennsylvania, the leading business school in the world. -

Research and Development

Annual Report 2010-11 Research and Development RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT FACULTY OF ARTS & HUMANITIES DEPARTMENT OF ARCHAEOLOGY Projects: (i) Completed UNESCO funded project ―Sui Vihar Excavations and Archaeological Reconnaissance of Southern Punjab” has been completed. Research Collaboration Funding grants for R&D o Pakistan National Commission for UNESCO approved project amounting to Rs. 0.26 million. DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE & LITERATURE Publications Book o Spatial Constructs in Alamgir Hashmi‘s Poetry: A Critical Study by Amra Raza Lambert Academic Publishing, Germany 2011 Conferences, Seminars and Workshops, etc. o Workshop on Creative Writing by Rizwan Akthar, Departmental Ph.D Scholar in Essex, October 11th , 2010, Department of English Language & Literature, University of the Punjab, Lahore. o Seminar on Fullbrght Scholarship Requisites by Mehreen Noon, October 21st, 2010, Department of English Language & Literature, Universsity of the Punjab, Lahore. Research Journals Department of English publishes annually two Journals: o Journal of Research (Humanities) HEC recognized ‗Z‘ Category o Journal of English Studies Research Collaboration Foreign Linkages St. Andrews University, Scotland DEPARTMENT OF FRENCH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE R & D-An Overview A Research Wing was introduced with its various operating desks. In its first phase a Translation Desk was launched: Translation desk (French – English/Urdu and vice versa): o Professional / legal documents; Regular / personal documents; o Latest research papers, articles and reviews; 39 Annual Report 2010-11 Research and Development The translation desk aims to provide authentic translation services to the public sector and to facilitate mutual collaboration at international level especially with the French counterparts. It addresses various businesses and multi national companies, online sales and advertisements, and those who plan to pursue higher education abroad. -

September 2014 Issue

Street Spirit Volume 20, No. 9 September 2014 Donation: $1.00 A publication of the American Friends Service Committee JUSTICE NEWS & HOMELESS BLUES IN THE B AY A REA A Quaker’s Ceaseless Quest for a World Without War by Terry Messman uring a long lifetime spent working for peace and social justice, David DHartsough has shown an uncanny instinct for being in the right place at the right time. One can almost trace the mod- ern history of nonviolent movements in America by following the trail of his acts of resistance over the past 60 years. His life has been an unbroken series of sit-ins for civil rights, seagoing blockades of munitions ships sailing for Vietnam, land blockades of trains carrying bombs to El Salvador, arrests at the Diablo nuclear reac- tor and the Livermore nuclear weapons lab, Occupy movement marches, and interna- tional acts of peacemaking in Russia, Nicaragua, Kosovo, Iran and Palestine. It all began at the very dawn of the Freedom Movement when the teenaged Hartsough met Martin Luther King and Ralph David Abernathy at a church in Montgomery, Alabama, in 1956 as the min- isters were organizing the bus boycott at the birth of the civil rights struggle. Next, while at Howard University, Hartsough was involved in some of the first “Where have all the flowers gone?” David Hartsough is arrested by police in San Francisco for blocking Photo credit: sit-ins to integrate restaurants in Arlington, Market Street in an act of civil disobedience in resistance to the U.S. invasion of Iraq. -

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email Id Remarks 9421864344 022 25401313 / 9869262391 Bhaveshwarikar

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email id Remarks 10001 SALPHALE VITTHAL AT POST UMARI (MOTHI) TAL.DIST- Male DEFAULTER SHANKARRAO AKOLA NAME REMOVED 444302 AKOLA MAHARASHTRA 10002 JAGGI RAMANJIT KAUR J.S.JAGGI, GOVIND NAGAR, Male DEFAULTER JASWANT SINGH RAJAPETH, NAME REMOVED AMRAVATI MAHARASHTRA 10003 BAVISKAR DILIP VITHALRAO PLOT NO.2-B, SHIVNAGAR, Male DEFAULTER NR.SHARDA CHOWK, BVS STOP, NAME REMOVED SANGAM TALKIES, NAGPUR MAHARASHTRA 10004 SOMANI VINODKUMAR MAIN ROAD, MANWATH Male 9421864344 RENEWAL UP TO 2018 GOPIKISHAN 431505 PARBHANI Maharashtra 10005 KARMALKAR BHAVESHVARI 11, BHARAT SADAN, 2 ND FLOOR, Female 022 25401313 / bhaveshwarikarmalka@gma NOT RENEW RAVINDRA S.V.ROAD, NAUPADA, THANE 9869262391 il.com (WEST) 400602 THANE Maharashtra 10006 NIRMALKAR DEVENDRA AT- MAREGAON, PO / TA- Male 9423652964 RENEWAL UP TO 2018 VIRUPAKSH MAREGAON, 445303 YAVATMAL Maharashtra 10007 PATIL PREMCHANDRA PATIPURA, WARD NO.18, Male DEFAULTER BHALCHANDRA NAME REMOVED 445001 YAVATMAL MAHARASHTRA 10008 KHAN ALIMKHAN SUJATKHAN AT-PO- LADKHED TA- DARWHA Male 9763175228 NOT RENEW 445208 YAVATMAL Maharashtra 10009 DHANGAWHAL PLINTH HOUSE, 4/A, DHARTI Male 9422288171 RENEWAL UP TO 05/06/2018 SUBHASHKUMAR KHANDU COLONY, NR.G.T.P.STOP, DEOPUR AGRA RD. 424005 DHULE Maharashtra 10010 PATIL SURENDRANATH A/P - PALE KHO. TAL - KALWAN Male 02592 248013 / NOT RENEW DHARMARAJ 9423481207 NASIK Maharashtra 10011 DHANGE PARVEZ ABBAS GREEN ACE RESIDENCY, FLT NO Male 9890207717 RENEWAL UP TO 05/06/2018 402, PLOT NO 73/3, 74/3 SEC- 27, SEAWOODS, -

Released 26Th July 2017 DARK HORSE COMICS MAY170038 BANKSHOT #2 MAY170025 BLACK HAMMER #11 MAIN ORMSTON CVR MAY170026 BLACK HAMM

Released 26th July 2017 DARK HORSE COMICS MAY170038 BANKSHOT #2 MAY170025 BLACK HAMMER #11 MAIN ORMSTON CVR MAY170026 BLACK HAMMER #11 VAR LEMIRE MAR170044 BLACK SINISTER HC MAY170066 BPRD DEVIL YOU KNOW #1 MAY170067 BPRD DEVIL YOU KNOW #1 MIGNOLA VAR APR170101 CONAN THE SLAYER #11 NOV160071 HOW TO WIN AT LIFE BY CHEATING AT EVERYTHING TP MAY170068 JOE GOLEM OCCULT DETECTIVE OUTER DARK #3 FEB170063 LEGEND OF KORRA TP VOL 01 TURF WARS PT 1 MAY170023 MASS EFFECT DISCOVERY #3 MAY170024 MASS EFFECT DISCOVERY #3 NIEMCZYK VAR MAY170028 REBELS THESE FREE & INDEPENDENT STATES #5 (OF 8) MAR170077 SERENITY HC VOL 05 NO POWER IN THE VERSE MAR170064 USAGI YOJIMBO SAGA LEGENDS LTD ED HC MAR170063 USAGI YOJIMBO SAGA LEGENDS TP DC COMICS MAY170198 ACTION COMICS #984 MAY170199 ACTION COMICS #984 VAR ED MAY170200 ALL STAR BATMAN #12 MAY170201 ALL STAR BATMAN #12 ALBUQUERQUE VAR ED MAY170202 ALL STAR BATMAN #12 FIUMARA VAR ED APR170417 AQUAMAN KINGDOM LOST TP MAY170205 BATGIRL #13 MAY170206 BATGIRL #13 VAR ED MAY170209 BATMAN BEYOND #10 MAY170210 BATMAN BEYOND #10 VAR ED APR170437 BATMAN SUPERMAN WONDER WOMAN TRINITY TP NEW EDITION MAY170290 BATMAN THE SHADOW #4 (OF 6) MAY170292 BATMAN THE SHADOW #4 (OF 6) EPTING VAR ED MAY170291 BATMAN THE SHADOW #4 (OF 6) SALE VAR ED MAY170217 BLUE BEETLE #11 MAY170218 BLUE BEETLE #11 VAR ED JAN170426 DC DESIGNER SER WONDER WOMAN BY ADAM HUGHES STATUE (RES) MAY170225 DETECTIVE COMICS #961 MAY170226 DETECTIVE COMICS #961 VAR ED MAY170314 DOOM PATROL #7 (RES) MAY170315 DOOM PATROL #7 VAR ED (RES) MAY170229 FLASH #27 MAY170230 -

Interpreting Race and Difference in the Operas of Richard Strauss By

Interpreting Race and Difference in the Operas of Richard Strauss by Patricia Josette Prokert A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Music: Musicology) in the University of Michigan 2020 Doctoral Committee: Professor Jane F. Fulcher, Co-Chair Professor Jason D. Geary, Co-Chair, University of Maryland School of Music Professor Charles H. Garrett Professor Patricia Hall Assistant Professor Kira Thurman Patricia Josette Prokert [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0002-4891-5459 © Patricia Josette Prokert 2020 Dedication For my family, three down and done. ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank my family― my mother, Dev Jeet Kaur Moss, my aunt, Josette Collins, my sister, Lura Feeney, and the kiddos, Aria, Kendrick, Elijah, and Wyatt―for their unwavering support and encouragement throughout my educational journey. Without their love and assistance, I would not have come so far. I am equally indebted to my husband, Martin Prokert, for his emotional and technical support, advice, and his invaluable help with translations. I would also like to thank my doctorial committee, especially Drs. Jane Fulcher and Jason Geary, for their guidance throughout this project. Beyond my committee, I have received guidance and support from many of my colleagues at the University of Michigan School of Music, Theater, and Dance. Without assistance from Sarah Suhadolnik, Elizabeth Scruggs, and Joy Johnson, I would not be here to complete this dissertation. In the course of completing this degree and finishing this dissertation, I have benefitted from the advice and valuable perspective of several colleagues including Sarah Suhadolnik, Anne Heminger, Meredith Juergens, and Andrew Kohler. -

The Newspaper Comic Strips Pdf, Epub, Ebook

HE-MAN AND THE MASTERS OF THE UNIVERSE: THE NEWSPAPER COMIC STRIPS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Chris Weber | 496 pages | 16 Feb 2017 | Dark Horse Comics,U.S. | 9781506700731 | English | Milwaukie, United States Masters of the Universe (comics) - Wikipedia Germany - Mattel - Masters of the Universe Germany - Ehapa Verlag - Masters of the Universe Germany - Ehapa Verlag - He-Man. Germany - Bastei - He-Man Germany - Dino-Panini Verlag - X India - Diamond Comics - Masters of the Universe Italy - Edigamma - Masters of the Universe Italy - Mondadori - Masters of the Universe - Netherlands - Junior Press - Masters of the Universe. Portugal - Impala Serbia - Politikin Zabavnik - Masters of the universe. Spain - Zinco - Atari Force Spain - Zinco - Princess of Power United Kingdom - Toontastic - X. Spain - Zinco - Masters of the Universe Some are Dark Horse's fault. Jan 14, Katie Cat Books rated it it was amazing. Adventure hero. Based on cartoon. Story: This book chronicles the He-Man newspaper comics from beginning to end. Characters: He- Man is in reality Prince Adam, with the secret ability to transform. He saves the day with the help of his friends, not just with brawn but with brains. Language: Very 80's dialogue. Full of cheesy lines and some morals. Contains suggestive adult content, but also appropriate reading for younger readers. While a lot of the dialogue with women is very sexist, women pl 80's. While a lot of the dialogue with women is very sexist, women play strong roles in the book and are often the heroes. A fun leap backwards in time, a nice distraction from my normal reading. Took some time to read because the book is so physically big it often causes cricks in my neck so I had to take lots of breaks! Dec 31, Vladimir rated it really liked it.