Urdu Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Module No. 1840 1840-1

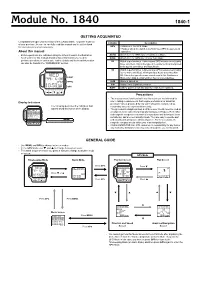

Module No. 1840 1840-1 GETTING ACQUAINTED Congratulations upon your selection of this CASIO watch. To get the most out Indicator Description of your purchase, be sure to carefully read this manual and keep it on hand for later reference when necessary. GPS • Watch is in the GPS Mode. • Flashes when the watch is performing a GPS measurement About this manual operation. • Button operations are indicated using the letters shown in the illustration. AUTO Watch is in the GPS Auto or Continuous Mode. • Each section of this manual provides basic information you need to SAVE Watch is in the GPS One-shot or Auto Mode. perform operations in each mode. Further details and technical information 2D Watch is performing a 2-dimensional GPS measurement (using can also be found in the “REFERENCE” section. three satellites). This is the type of measurement normally used in the Quick, One-Shot, and Auto Mode. 3D Watch is performing a 3-dimensional GPS measurement (using four or more satellites), which provides better accuracy than 2D. This is the type of measurement used in the Continuous LIGHT Mode when data is obtained from four or more satellites. MENU ALM Alarm is turned on. SIG Hourly Time Signal is turned on. GPS BATT Battery power is low and battery needs to be replaced. Precautions • The measurement functions built into this watch are not intended for Display Indicators use in taking measurements that require professional or industrial precision. Values produced by this watch should be considered as The following describes the indicators that reasonably accurate representations only. -

Snow Leopard Survival Strategy 2014

Snow Leopard Survival Strategy Revised Version 2014.1 Snow Leopard Network 1 The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Snow Leopard Network concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Copyright: © 2014 Snow Leopard Network, 4649 Sunnyside Ave. N. Suite 325, Seattle, WA 98103. Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorised without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. Citation: Snow Leopard Network (2014). Snow Leopard Survival Strategy. Revised 2014 Version Snow Leopard Network, Seattle, Washington, USA. Website: http://www.snowleopardnetwork.org/ The Snow Leopard Network is a worldwide organization dedicated to facilitating the exchange of information between individuals around the world for the purpose of snow leopard conservation. Our membership includes leading snow leopard experts in the public, private, and non-profit sectors. The main goal of this organization is to implement the Snow Leopard Survival Strategy (SLSS) which offers a comprehensive analysis of the issues facing snow leopard conservation today. Cover photo: Camera-trapped snow leopard. © Snow Leopard -

Moüjmtaiim Operations

L f\f¿ áfó b^i,. ‘<& t¿ ytn) ¿L0d àw 1 /1 ^ / / /This publication contains copyright material. *FM 90-6 FieW Manual HEADQUARTERS No We DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY Washington, DC, 30 June 1980 MOÜJMTAIIM OPERATIONS PREFACE he purpose of this rUanual is to describe how US Army forces fight in mountain regions. Conditions will be encountered in mountains that have a significant effect on. military operations. Mountain operations require, among other things^ special equipment, special training and acclimatization, and a high decree of self-discipline if operations are to succeed. Mountains of military significance are generally characterized by rugged compartmented terrain witn\steep slopes and few natural or manmade lines of communication. Weather in these mountains is seasonal and reaches across the entireSspectrum from extreme cold, with ice and snow in most regions during me winter, to extreme heat in some regions during the summer. AlthoughNthese extremes of weather are important planning considerations, the variability of weather over a short period of time—and from locality to locahty within the confines of a small area—also significantly influences tactical operations. Historically, the focal point of mountain operations has been the battle to control the heights. Changes in weaponry and equipment have not altered this fact. In all but the most extreme conditions of terrain and weather, infantry, with its light equipment and mobility, remains the basic maneuver force in the mountains. With proper equipment and training, it is ideally suited for fighting the close-in battfe commonly associated with mountain warfare. Mechanized infantry can\also enter the mountain battle, but it must be prepared to dismount and conduct operations on foot. -

Module No. 2240 2240-1

Module No. 2240 2240-1 GETTING ACQUAINTED Precautions • Congratulations upon your selection of this CASIO watch. To get the most out The measurement functions built into this watch are not intended for of your purchase, be sure to carefully read this manual and keep it on hand use in taking measurements that require professional or industrial for later reference when necessary. precision. Values produced by this watch should be considered as reasonably accurate representations only. About This Manual • Though a useful navigational tool, a GPS receiver should never be used • Each section of this manual provides basic information you need to perform as a replacement for conventional map and compass techniques. Remember that magnetic compasses can work at temperatures well operations in each mode. Further details and technical information can also be found in the “REFERENCE”. below zero, have no batteries, and are mechanically simple. They are • The term “watch” in this manual refers to the CASIO SATELLITE NAVI easy to operate and understand, and will operate almost anywhere. For Watch (Module No. 2240). these reasons, the magnetic compass should still be your main • The term “Watch Application” in this manual refers to the CASIO navigation tool. • SATELLITE NAVI LINK Software Application. CASIO COMPUTER CO., LTD. assumes no responsibility for any loss, or any claims by third parties that may arise through the use of this watch. Upper display area MODE LIGHT Lower display area MENU On-screen indicators L K • Whenever leaving the AC Adaptor and Interface/Charger Unit SAFETY PRECAUTIONS unattended for long periods, be sure to unplug the AC Adaptor from the wall outlet. -

Synthesis Report on Ten ASEAN Countries Disaster Risks Assessment

Synthesis Report on Ten ASEAN Countries Disaster Risks Assessment ASEAN Disaster Risk Management Initiative December 2010 Preface The countries of the Association of Southeast (Vietnam) droughts, September 2009 cyclone Asian Nations (ASEAN), which comprises Brunei, Ketsana (known as Ondoy in the Philippines), Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, catastrophic flood of October 2008, and January Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam, is 2007 flood (Vietnam), September 1997 forest-fire geographically located in one of the most disaster (Indonesia) and many others. Climate change is prone regions of the world. The ASEAN region expected to exacerbate disasters associated with sits between several tectonic plates causing hydro-meteorological hazards. earthquakes, volcanic eruptions and tsunamis. The region is also located in between two great Often these disasters transcend national borders oceans namely the Pacific and the Indian oceans and overwhelm the capacities of individual causing seasonal typhoons and in some areas, countries to manage them. Most countries in tsunamis. The countries of the region have a the region have limited financial resources and history of devastating disasters that have caused physical resilience. Furthermore, the level of economic and human losses across the region. preparedness and prevention varies from country Almost all types of natural hazards are present, to country and regional cooperation does not including typhoons (strong tropical cyclones), exist to the extent necessary. Because of this high floods, earthquakes, tsunamis, volcanic eruptions, vulnerability and the relatively small size of most landslides, forest-fires, and epidemics that of the ASEAN countries, it will be more efficient threaten life and property, and droughts that leave and economically prudent for the countries to serious lingering effects. -

Chapter 1 Introduction to the Geology of Myanmar

Downloaded from http://mem.lyellcollection.org/ by guest on October 2, 2021 Chapter 1 Introduction to the geology of Myanmar KHIN ZAW1*, WIN SWE2, A. J. BARBER3, M. J. CROW4 & YIN YIN NWE5 1CODES ARC Centre of Excellence in Ore Deposits, University of Tasmania, Private Bag 126, Hobart, Tasmania 7001, Australia 2Myanmar Geosciences Society, 303 MES Building, Hlaing University Campus, Yangon, Myanmar 3Department of Earth Sciences, Southeast Asian Research Group, Royal Holloway, Egham TW20 0EX, UK 428a Lenton Road, The Park, Nottingham NG7 1DT, UK 5Myanmar Applied Earth Sciences Association (MAESA), 15 (C) Pyidaungsu Lane, Bahan, Yangon, Myanmar *Correspondence: [email protected] Gold Open Access: This article is published under the terms of the CC-BY 3.0 license. The Republic of the Union of Myanmar (Pyidaungsu Tham- northern part of the Andaman Sea and the Gulf of Mottama mada Myanmar NaingNganDaw), formerly Burma, occupies (Martaban). The central lowlands are divided into two unequal the northwestern part of the Southeast Asian peninsula. It is parts by the Bago Yoma Ranges, the larger Ayeyarwaddy Valley bounded to the west by India, Bangladesh, the Bay of Bengal and the smaller Sittaung Valley. The Bago Yoma Ranges pass and the Andaman Sea, and to the east by China, Laos and Thai- northwards into a line of extinct volcanoes with small crater land. It comprises seven administrative regions (Ayeyarwaddy lakes and eroded cones; the largest of these is Mount Popa (Irrawaddy), Bago, Magway, Mandalay, Sagaing, Tanintharyi (1518 m). Coastal lowlands and offshore islands margin the (Tenasserim) and Yangon) and seven states (Chin, Kachin, Bay of Bengal to the west of the Rakhine Yoma and the Anda- Kayah, Kayin, Mon, Rakhine (Arakan) and Shan). -

A New Species of Murina (Chiroptera: Vespertilionidae) from Sub-Himalayan Forests of Northern Myanmar

Zootaxa 4320 (1): 159–172 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) http://www.mapress.com/j/zt/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2017 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4320.1.9 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:5522DFE5-9C8D-4835-AC0C-4E3CAFC232B5 A new species of Murina (Chiroptera: Vespertilionidae) from sub-Himalayan forests of northern Myanmar PIPAT SOISOOK1,6, WIN NAING THAW2, MYINT KYAW2, SAI SEIN LIN OO3, AWATSAYA PIMSAI1, 4, MARCELA SUAREZ-RUBIO5 & SWEN C. RENNER5 1Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn Natural History Museum, Faculty of Science, Prince of Songkla University, Hat Yai, Songkhla, Thailand, 90110 2Nature and Wildlife Conservation Division, Forest Department, Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Conservation, Yarzar Htar Ni Road, Nay Pyi Taw, Myanmar 3Department of Zoology, University of Mandalay, Mandalay Region, Myanmar 4Harrison Institute, Bowerwood House, St. Botolph’s Road, Sevenoaks, Kent, TN13 3AQ, United Kingdom 5Institute of Zoology, University of Natural Resources and Life Science, Gregor-Mendel-Straße 33/I 1180 Vienna, Austria 6Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract A new species of Murina of the suilla-type is described from the Hkakabo Razi Landscape, Kachin, Upper Myanmar, an area that is currently being nominated as a World Heritage Site. The new species is a small vespertilionid, with a forearm length of 29.6 mm, and is very similar to M. kontumensis, which was recently described from Vietnam. However, it is distinguishable by a combination of external and craniodental morphology and genetics. The DNA Barcode reveals that the new species clusters sisterly to M. kontumensis but with a genetic distance of 11.5%. -

India Neighbouring Countries

India Neighbouring Countries Recruitment.guru www.recruitment.guru/current-affairs List of India's Neighbouring Countries with their Capitals India shares its borders with nine countries. A Name of the country and its capitals, connecting states, border names, and the length of the border details are listed below. Neighbouring Country: Pakistan Capital: Islamabad Bordering States: Jammu and Kashmir, Punjab, Rajasthan & Gujarat Name of the Border: Radcliffe Line Border Length: 3323 km Neighbouring Country: Afghanistan Capital: Kabul Bordering States: Ladakh (PoK) Name of the Border: Durand Line Border Length: 106 km Neighbouring Country: Bangladesh Capital: Dhaka Bordering States: West Bengal, Mizoram, Tripura, Meghalaya & Assam Name of the Border: Purbachal Border Length: 4096 km Neighbouring Country: Bhutan Capital: Thimphu Bordering States: West Bengal, Mizoram, Tripura, Arunachal Pradesh & Assam Name of the Border: Indo-Bhutan Border Length: 699 km Neighbouring Country: China Capital: Beijing Bordering States: Uttarakhand, Sikkim Ladakh, Himachal Pradesh, and Arunachal Pradesh Name of the Border: McMohan Line Border Length: 3488 km Neighbouring Country: Srilanka Capital: Colombo Bordering States: Separated by Palk Strait Name of the Border: Palk Strait (Sea Border) Border Length: 30 km Neighbouring Country: Nepal Capital: Kathmandu Bordering States: Bihar, West Bengal, Uttarakhand, Uttar Pradesh & Sikkim Name of the Border: Sunauli Border Length: 70 km www.recruitment.guru/current-affairs Neighbouring Country: Myanmar Capital: Naypyidaw, Yangon Bordering States: Arunachal Pradesh, Mizoram, Manipur, and Nagaland Name of the Border: Indo-Burma barrier Border Length: 1643 km Neighbouring Country: Maldives Capital: Male Bordering States: It is South-West of India below the Laksha deep ocean Name of the Border: Sea Border Border Length: 675 km Facts about Neighbouring Countries of India | List of India's Neighbouring Countries The Major facts of India's Neighbouring countries are listed below. -

Magazine July/August 2008

SABICJuly/August 2008 Issue 87 SABIC InnovatIVE PlastICS WINS 2007 NAtional ENERGY gLOBE AWArD KINg ABDULLAH LAUNCHES Sr68BN PrOJECtS IN JUBAIL SABIC, SINOPEC sigN StrAtEgic cooperAtion Agreement CHArLIE CrEW: tHE NEW PrESIDENt & CEO OF SABIC INNOVAtIVE PLAStICS FOrEWOrD Greetings to all of our readers around the world and welcome to issue 87 of SAbIc magazine. We bring you news of several key appointments, including charlie crew who was promoted to president and cEO of SAbIc Innovative Plastics. We also have a detailed report on the globally implemented SAbIc Integration Program. The initiative is designed to streamline operations across the three Sharing our futures SAbIc businesses and to ensure they are all growing in the same direction. Further successes are SAbIc’s reported first quarter 2008 (1Q08) profits of 7 SABIC tO mArKEt Saudi ArAmco’S CHINESE 11 SABIC INNOVAtIVE PLAStICS At EUrO 2008 SR6.92 billion (US$1.85bn), compared with SR6.28 billion for the same period in 2007. joint VENtUrE PrODUCtS We bring you the details of a speech SAbIc’s Vice chairman and cEO, Mohamed Al-Mady, gave at the Financial Times china-Middle East Summit, held in Riyadh, in which he outlined the strategic partnership Saudi Arabia has with china. Additionally, at chinaplas 2008, SAbIc Innovative Plastics announced a 5-22 NEWS: The inside story with news, views multi-pronged strategy to meet its customer needs through an expansion of and comments general Supervisor: Mohamed H. Al-Mady local expertise and product fulfilment. Vice-chairman and cEO 23 COVEr StOrY: SAbIc Innovative Plastics In Europe, we have news of the SAbIc family of automotive businesses, from wins 2007 National Energy Globe SAbIc Innovative Plastics, SAbIc Europe, and Exatec, exhibiting together for the Editor-in-Chief: Othman M. -

Conflict of Interests CMYK

Part Two: Logging in Burma / 19 The China-Burma Border processed here originates in Burma. Workers in the increasing presence of the SPDC had led to more Yingjian told Global Witness that the Tatmadaw had taxation. Both accounts suggest that logging was held Chinese loggers hostage in Burma until the becoming less profitable. Local people told Global companies paid ransoms of approximately 10,000 yuan Witness that both the KIO and the SPDC controlled the ($1200) per person.327 forests and border crossing.327 19.5.3.3 Hong Bom He 19.5.3.5 Xima Hong Bom He Town is situated on the Hong Bom There was no indication that the small town of Xima River inside the Tonbiguan Nature Reserve. The town had anything to do with logging although it is well was built in 1993 after private companies illegally built a connected to the border.327 logging road to the Burmese border ostensibly with the consent of local Chinese authorities.327 The town is 19.5.3.6 Car Zan illegal insofar as it was built after the area was Car Zan is a busy logging town with two large designated a nature reserve. stockpiles of logs and approximately 30 sawmills in In 2000 there were 2,000 people working in the 2001.327 The town has been associated with logging for town and in the forests across the border in Kachin 10 years and is opposite KIO controlled areas.327 Global State, although by early 2001 the town appeared to be Witness investigators saw more than 20 log trucks, each closing down and was effectively working at 20% carrying nine m3 of logs, entering the town in a period capacity or less.327 There was still some log trading of an hour and a half, suggesting that the town is more activity with Chinese logging trucks and stockpiles of important for the timber trade than the number of wood present on the Burmese side of the river. -

Toungoo Dynasty: the Second Burmese Empire (1486 –1752)

BURMA in Perspective TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1: GEOGRAPHY......................................................................................................... 1 Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 1 Geographic Divisions .............................................................................................................. 1 Western Mountains ........................................................................................................... 2 Northern Mountains .......................................................................................................... 2 Shan Plateau ..................................................................................................................... 3 Central Basin and Lowlands ............................................................................................. 3 Coastal Strip ..................................................................................................................... 4 Climate ..................................................................................................................................... 4 Bodies of Water ....................................................................................................................... 5 Irrawaddy (Ayeyarwady) River ........................................................................................ 6 Sittang River .................................................................................................................... -

GK Facts About India's Neighboring Countries

www.gradeup.co 1 www.gradeup.co GK Facts about India’s Neighboring Countries 1. Sri lanka Some Important Facts President Gotabaya Rajapaksa Prime Minister Mahindra Rajapaksa Chief Justice Jayantha Jayasuriya Official languages Sinhala,Tamil State/ Provinces 9 states Capital Sri Jayawardenepura Kotte largest city Colombo Currency Sri Lankan Rupee (LKR) National Game Volleyball National Bird Ceylon (Jungle Fowl) National Animal Grizzled Giant Squirrel National Fruit Jackfruit National Tree Ironwood National Flower Blue water lily Highest peak Pidurutalagala Longest river Mahaweli Religion 70.2% Buddhism, 12.6% Hinduism Parliament Parliamenthua (225 seats) Famous Sinhala and Tamil New Year, Vesak, Poson Festival, Kandy Esala Perahera, festivals Kataragama Festival, Vel Festival, Deepavali 2 www.gradeup.co 2. China Some Important Facts President Xi Jinping Official Mandarin languages State/ Provinces 26 Provinces Capital Beijing Currency Sri Lankan Rupee (LKR) National Game Table Tennis National Bird Red-crowned crane National Fruit Kiwifruit National Tree Maidenhair tree National Flower Blue water lily National animal Giant Panda Longest river Yangtze River Jammu and Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh, Sikkim, Uttarakhand and Arunachal Boundaries Pradesh Parliament National Assembly (2980 members) Border McMahon Line 3. Myammar Some Important Facts President Win Myint Prime Minister Min Aung Hliaing National anthem Kaba Ma Kyei Official languages Burmese National animal Tiger Capital and largest city Naypyidaw Currency Burmese Kyat National Game Caneball