Final Report APL Project 2017/2217

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"First Report on the State of the World's Animal Genetic Resources"

Country Report of Australia for the FAO First Report on the State of the World’s Animal Genetic Resources 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY................................................................................................................5 CHAPTER 1 ASSESSING THE STATE OF AGRICULTURAL BIODIVERSITY THE FARM ANIMAL SECTOR IN AUSTRALIA.................................................................................7 1.1 OVERVIEW OF AUSTRALIAN AGRICULTURE, ANIMAL PRODUCTION SYSTEMS AND RELATED ANIMAL BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY. ......................................................................................................7 Australian Agriculture - general context .....................................................................................7 Australia's agricultural sector: production systems, diversity and outputs.................................8 Australian livestock production ...................................................................................................9 1.2 ASSESSING THE STATE OF CONSERVATION OF FARM ANIMAL BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY..............10 Major agricultural species in Australia.....................................................................................10 Conservation status of important agricultural species in Australia..........................................11 Characterisation and information systems ................................................................................12 1.3 ASSESSING THE STATE OF UTILISATION OF FARM ANIMAL GENETIC RESOURCES IN AUSTRALIA. ........................................................................................................................................................12 -

PAC-FIRE-CATALOG-1.Pdf

CALL FOR NEW PRICE LIST! OUR COMMITMENT TO THE TEAM APPROACH INCLUDES YOU, OUR NUMBER ONE PRIORITY. We take pride in being YOUR FIRST CHOICE for proper, safe and efficient tool mounting! PAC Founder/Owner: Dick Young Sales Team: Dean Mayhew, Greg Young, Vice President: Greg Young Tammy Trzepacz, Tom Trzepacz, Mike McGuire President: Jim Everett Performance Advantage Company Team In the past 25 years PAC has grown from the basement of company founder Dick Young to an operation with over 600 points of distribution in North America and sales in 38 countries around the globe. All this based on the concept of offering Top Quality products combined with the very best Customer Service. The cornerstone of all this is based on our outstanding staff members. They are committed to giving our customers the very best in assistance and overall customer service. Our history of innovation and our collective experience guide PAC to create products to outlast and outperform. You can expect high quality and value when purchasing PAC products. We are highly recognized in the industries we serve for our attention to detail and overall customer service. Additionally, PAC products are tested to the highest standards and are compliant with National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) 1901 standards and MIL-S901D military shock specifications. And PAC offers a LIFETIME WARRANTY! If any PAC product fails under normal use it is replaced, free of charge. In recent years we have grown beyond the Fire Market. We have applied our tool mounting knowledge to customers in Law Enforcement, Towing and Tow Vehicles, Homeland Security, Public Utility and the Green Industry, too. -

Farming and Biodiversity of Pigs in Bhutan

Animal Genetic Resources, 2011, 48, 47–61. © Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2011 doi:10.1017/S2078633610001256 Farming and biodiversity of pigs in Bhutan K. Nidup1,2, D. Tshering3, S. Wangdi4, C. Gyeltshen5, T. Phuntsho5 and C. Moran1 1Centre for Advanced Technologies in Animal Genetics and Reproduction (REPROGEN), Faculty of Veterinary Science, University of Sydney, Australia; 2College of Natural Resources, Royal University of Bhutan, Lobesa, Bhutan; 3Department of Livestock, National Pig Breeding Centre, Ministry of Agriculture, Thimphu, Bhutan; 4Department of Livestock, Regional Pig and Poultry Breeding Centre, Ministry of Agriculture, Lingmithang, Bhutan; 5Department of Livestock, Regional Pig and Poultry Breeding Centre, Ministry of Agriculture, Gelephu, Bhutan Summary Pigs have socio-economic and cultural importance to the livelihood of many Bhutanese rural communities. While there is evidence of increased religious disapproval of pig raising, the consumption of pork, which is mainly met from imports, is increasing every year. Pig development activities are mainly focused on introduction of exotic germplasm. There is an evidence of a slow but steady increase in the population of improved pigs in the country. On the other hand, indigenous pigs still comprise 68 percent of the total pig population but their numbers are rapidly declining. If this trend continues, indigenous pigs will become extinct within the next 10 years. Once lost, this important genetic resource is largely irreplaceable. Therefore, Government of Bhutan must make an effort to protect, promote and utilize indigenous pig resources in a sustainable manner. In addition to the current ex situ conservation programme based on cryopre- servation of semen, which needs strengthening, in situ conservation and a nucleus farm is required to combat the enormous decline of the population of indigenous pigs and to ensure a sustainable source of swine genetic resources in the country. -

Smoke Signals Volume 6 Table of Contents Welcome to Firefighter Bootcamp

June 2007 Smoke Signals Volume 6 Table of Contents Welcome to Firefighter Bootcamp Administration..........3 ~ The Sycuan Rookie Training Budget......................6 Model Dave Koch, NIFC Fire Use/Fuels...........7 ~ Planning....................9 Prevention...............11 Training..................14 Blacksnakes Corner.15 Publishers & Info...Back Sycuan Academy included helicopter operations training. ~ Photo Gary G. Ballard It’s Sunday afternoon and firefighter who quickly inspects the disheveled students recruits slowly assemble at the academy and indoctrinates them with academy barracks. They come from various parts of philosophy, expectations, procedures, and the country, representing diverse cultural logistics. (Chief Murphy implemented his and economic backgrounds. All have one academy vision 10 years ago.) thing in common: to experience a firefighter rookie training program unlike anything else The next order of business is gear issuance, in the country. There are a lot of unknowns. the shaving of heads (yes, it all comes off), Mysterious stories about past academies and the first round of physical training flow from one student to the next. Nervous for the day. Each academy day begins at anticipation builds. 5:00am with intense physical training as the first order of business. The recruits do At 1400, students are prodded to attention PT twice a day, sometime more. Those by the barking of instructions from former that last the entire 21 days can expect to be Marine Corps drill instructors (DIs). stronger, faster, and have more endurance Students quickly form two lines as the DIs’ than they’ve ever had. There is a physical order them to stand at attention. They are transformation that takes place with these introduced to the founder of the Academy, recruits. -

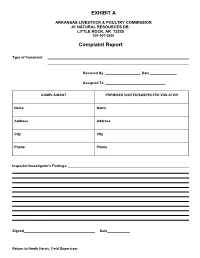

Complaint Report

EXHIBIT A ARKANSAS LIVESTOCK & POULTRY COMMISSION #1 NATURAL RESOURCES DR. LITTLE ROCK, AR 72205 501-907-2400 Complaint Report Type of Complaint Received By Date Assigned To COMPLAINANT PREMISES VISITED/SUSPECTED VIOLATOR Name Name Address Address City City Phone Phone Inspector/Investigator's Findings: Signed Date Return to Heath Harris, Field Supervisor DP-7/DP-46 SPECIAL MATERIALS & MARKETPLACE SAMPLE REPORT ARKANSAS STATE PLANT BOARD Pesticide Division #1 Natural Resources Drive Little Rock, Arkansas 72205 Insp. # Case # Lab # DATE: Sampled: Received: Reported: Sampled At Address GPS Coordinates: N W This block to be used for Marketplace Samples only Manufacturer Address City/State/Zip Brand Name: EPA Reg. #: EPA Est. #: Lot #: Container Type: # on Hand Wt./Size #Sampled Circle appropriate description: [Non-Slurry Liquid] [Slurry Liquid] [Dust] [Granular] [Other] Other Sample Soil Vegetation (describe) Description: (Place check in Water Clothing (describe) appropriate square) Use Dilution Other (describe) Formulation Dilution Rate as mixed Analysis Requested: (Use common pesticide name) Guarantee in Tank (if use dilution) Chain of Custody Date Received by (Received for Lab) Inspector Name Inspector (Print) Signature Check box if Dealer desires copy of completed analysis 9 ARKANSAS LIVESTOCK AND POULTRY COMMISSION #1 Natural Resources Drive Little Rock, Arkansas 72205 (501) 225-1598 REPORT ON FLEA MARKETS OR SALES CHECKED Poultry to be tested for pullorum typhoid are: exotic chickens, upland birds (chickens, pheasants, pea fowl, and backyard chickens). Must be identified with a leg band, wing band, or tattoo. Exemptions are those from a certified free NPIP flock or 90-day certificate test for pullorum typhoid. Water fowl need not test for pullorum typhoid unless they originate from out of state. -

ACE Appendix

CBP and Trade Automated Interface Requirements Appendix: PGA August 13, 2021 Pub # 0875-0419 Contents Table of Changes .................................................................................................................................................... 4 PG01 – Agency Program Codes ........................................................................................................................... 18 PG01 – Government Agency Processing Codes ................................................................................................... 22 PG01 – Electronic Image Submitted Codes .......................................................................................................... 26 PG01 – Globally Unique Product Identification Code Qualifiers ........................................................................ 26 PG01 – Correction Indicators* ............................................................................................................................. 26 PG02 – Product Code Qualifiers ........................................................................................................................... 28 PG04 – Units of Measure ...................................................................................................................................... 30 PG05 – Scientific Species Code ........................................................................................................................... 31 PG05 – FWS Wildlife Description Codes ........................................................................................................... -

Selected Readings on the History and Use of Old Livestock Breeds

NATIONAL AGRICULTURAL LIBRARY ARCHIVED FILE Archived files are provided for reference purposes only. This file was current when produced, but is no longer maintained and may now be outdated. Content may not appear in full or in its original format. All links external to the document have been deactivated. For additional information, see http://pubs.nal.usda.gov. Selected Readings on the History and Use of Old Livestock Breeds United States Department of Agriculture Selected Readings on the History and Use of Old Livestock Breeds National Agricultural Library September 1991 Animal Welfare Information Center By: Jean Larson Janice Swanson D'Anna Berry Cynthia Smith Animal Welfare Information Center National Agricultural Library U.S. Department of Agriculture And American Minor Breeds Conservancy P.O. Box 477 Pittboro, NC 27312 Acknowledgement: Jennifer Carter for computer and technical support. Published by: U. S. Department of Agriculture National Agricultural Library Animal Welfare Information Center Beltsville, Maryland 20705 Contact us: http://awic.nal.usda.gov/contact-us Web site: www.nal.usda.gov/awic Published in cooperation with the Virginia-Maryland Regional College of Veterinary Medicine Policies and Links Introduction minorbreeds.htm[1/15/2015 2:16:51 PM] Selected Readings on the History and Use of Old Livestock Breeds For centuries animals have worked with and for people. Cattle, goats, sheep, pigs, poultry and other livestock have been an essential part of agriculture and our history as a nation. With the change of agriculture from a way of life to a successful industry, we are losing our agricultural roots. Although we descend from a nation of farmers, few of us can name more than a handful of livestock breeds that are important to our production of food and fiber. -

Montana Farmer-Stockman Reaches REGISTERED HAMPSHIRE Rams for Sale—Jim Good Home

■ I s r ■ a m. E APPALOOSAS & P.O.A.s, Stud Prospects, 4-H WESTERN MONTANA—$25,000 down payment colts. Fillies and mares. Cecil Bilbre, Choteau, buys beautiful ranch including 200 top Hereford O I o e Montana. Phone 466-2246. _____________ cows, full line machinery, 800 tons hay, supplies and tools. Owner retiring—will leave his capi 4 I ONE “SHETLAND STALLION, registered. Cres j cent Breeding—gentle. Hazel French, Route 1, tal invested in the ranch. Location incomparable —within walking distance of grade and high Lewistown. Montana. _________________________ schools. Easy operation—good fall and winter i •BUYING SHEEP ___________ grazing. Private (free) water rights. Very low a/Cs, jot CHOICE PUREBRED HAMPSHIRE rams for taxes. Two modern homes. Heavy calves. This I •SELLING sale, lambs and yearlings. Mt. Haggin Breeding. is a top outfit. FISHER REALTY, Phone 745- Harry Miller, Star Route, Bozeman. Montana. 3101. St. Ignatius. Montana._______________________ K TOP GROCERY $200,000 volume. 175 acre river 3 FOR SALE—70 head ewes, 2 to 4 years old, •TRADING bottom, sprinkler system, business machines- $15.00 per head. Andrew Teterud, Dixon, Mon ; I tana. Phone 726-3126. __________________________________ office furniture, a money maker. Exclusive mu i sic store. Motel priced low. 40 acre river front, The rate is very low for our big circulation. Montana Farmer-Stockman reaches REGISTERED HAMPSHIRE rams for sale—Jim good home. 540 acre wheat farm, creek, modern I nearly nine out of every ten farm and ranch families in Montana with additional Moore, Rt. No. 2, Belgrade, Montana. Phone home. -

A Newsletter from Marcus Oldham College Old Students Association

A ne wsle tter from M arcus y 2012 Oldham C Januar ollege Old S • Issue 1 • tudents Association Volume 19 A ne wsl etter from Marcus 2012 Oldham January College Old Issue 1 • Students Association Volume 19 • The Principal’s Perspective y the time this edition of MOCOSA goes to print promote and implement sound economic strategies to improve and is distributed, the 2011 graduation will be over the quality of life of people in their areas. Time was spent with and another group of graduates will have entered local councils seeing how communities develop their capacity to B create a prosperous and sustainable future through co-ordination, the workforce. A real strength of the College is the large number of alumni who go on to be successful ambassadors collaboration and effective use of public and private resources. in their chosen field of endeavour. The success of Marcus My objective in visiting these establishments was to learn what I Oldham as an institution is the result, in part, of the efforts could about rural entrepreneurialism, what it is and what makes and high profile of our achieving alumni. for success, and to bring that knowledge back to Marcus Oldham College for further development among our students. Australia During the year the College made submissions to both the has a proud record of agricultural and equine achievement Victorian State and the Federal Inquiries into agricultural education through entrepreneurialism, even if we don’t call it that. and workforce planning. These Inquiries will endeavour to identify the reasons why agricultural enrolments are declining Whilst in the United States, I reflected on the work of a leading nationally and why more young people are not pursuing careers educator and researcher, Professor Ron Ritchhart, who holds in agriculture. -

Biodiversity of Pig Breeds from China and Europe Estimated from Pooled DNA Samples: Differences in Microsatellite Variation Between Two Areas of Domestication

Genet. Sel. Evol. 40 (2008) 103–128 Available online at: c INRA, EDP Sciences, 2008 www.gse-journal.org DOI: 10.1051/gse:2007039 Original article Biodiversity of pig breeds from China and Europe estimated from pooled DNA samples: differences in microsatellite variation between two areas of domestication Hendrik-Jan Megens1∗,RichardP.M.A.Crooijmans1, Magali San Cristobal2,XiaoHui3,NingLi3, Martien A.M. Groenen1 1 Wageningen University, Animal Breeding and Genomics Centre, PO Box 338, 6700AH, Wageningen, The Netherlands 2 INRA, UMR444 Laboratoire de génétique cellulaire, 31326 Castanet Tolosan, France 3 China Agricultural University, National Laboratories for Agrobiotechnology, Yuanmingyuan West Road 2, Haidian District, 100094 Beijing, P.R. China (Received 24 July 2006; accepted 18 July 2007) Abstract – Microsatellite diversity in European and Chinese pigs was assessed using a pooled sampling method on 52 European and 46 Chinese pig populations. A Neighbor Joining analysis on genetic distances revealed that European breeds were grouped together and showed little evidence for geographic structure, although a southern European and English group could ten- tatively be assigned. Populations from international breeds formed breed specific clusters. The Chinese breeds formed a second major group, with the Sino-European synthetic Tia Meslan in-between the two large clusters. Within Chinese breeds, in contrast to the European pigs, a large degree of geographic structure was noted, in line with previous classification schemes for Chinese pigs that were based on morphology and geography. The Northern Chinese breeds were most similar to the European breeds. Although some overlap exists, Chinese breeds showed a higher average degree of heterozygosity and genetic distance compared to European ones. -

September, 1936 . Club Series No. 10 LIVESTOCK JUDGING for 4-H CLUB MEMBERS (A Revision of Extension Circular No. 131) NORTH

September, 1936 . Club Series No. 10 LIVESTOCK JUDGING FOR 4-H CLUB MEMBERS (A revision of Extension Circular No. 131) NORTH CAROLINA STATE COLLEGE OF AGRICULTURE AND ENGINEERING AND U. 5. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE. CO-OPERATING NORTH CAROLINA AGRICULTURAL EXTENSION SERVICE I. O. SCHAUB. DIRECTOR STATE COLLEGE STATION RALEIGH, NORTH CAROLINA DISTRIBUTED IN FURTHERANCE OF THE ACTS OF CONGRESS OF MAY 8 AND JUNE 30, 1914 LIVESTOCK JUDGING FOR 4-H CLUB MEMBERS INTRODUCTION Because of its value in teaching the fundamental facts regard- ing the types, characteristics and functions of farm animals, Livestock Judging is considered a definite part of our 4-H Live- stock projects. To make this a more valuable project this bulletin has been prepared. It represents the best thought and the most accurate information available, and has been assembled in a form understandable to farm boys and girls. Every farm boy and girl should be a good judge of livestock. North Carolina needs more and better livestock in order to have a more profitable system of agriculture; to maintain soil fertility; and to supply the necessary food and feed supply for man and animals. Good livestock is essential to a profitable program of agriculture. A correct knowledge of good livestock is a prerequisite to good livestock. Therefore it is our hope that through 4-H livestock projects and especially through livestock judging that the 4-H Club Member will learn to recognize the good? as well as the undesirable types and characteristics of live- stockand that as a result of this training and information North Carelina will have more and better livestock. -

Feast and Famine in the National Parks

The Journal of the Association of National Park Rangers RangerStewards for parks, visitors & each other Vol. 29, No. 4 | Fall 2013 A Public Harvest – Feast and Famine in the National Parks RANGER • Fall 2013 u Sec1a Share your views! Do you have a comment on a particular topic featured in this issue? Or about anything related to national parks? Send your views to fordedit@ aol.com or to the address on the back cover. More reminiscing about housing Reading Leslie Spurlin’s article, “NPS housing – A look back” (Summer 2013) brought back memories of my own. My first assignment was in Canyonlands, Needles District, 1974- 79. Each district had two to four permanent employees, a large handful of long-term sea- sonals who returned year after year and often volunteered for the park in the off-season, and a few Student Conservation Association workers who rotated through every 12 weeks or so. Communication with headquarters was Preregister online at www.anpr.org. Program via the park’s two-way radio system and occa- sionally (mostly at night) by radio telephone. details are posted there, with a summary on One channel served southeastern Utah and a small part of Colorado. One AM radio station page 21. See you Oct. 27 – 31 in St. Louis. came in about an hour after dark. Prior to my arrival, I was told that housing playing. The evening ranger, someone with less consisted of trailers that “were left over from experience, came back to his trailer. He quickly the Johnstown flood.” I didn’t look up that ran over to the court and excitedly reported that reference until much later, but the trailers were the generator was out.