Farming and Biodiversity of Pigs in Bhutan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View English PDF Version

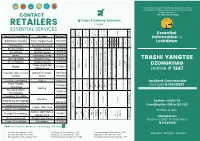

on ” 1247 17608432 17343588 Please stay alert. Chairperson His Majesty The King Hotline # 4141 Essential Lockdown Eastern COVID-19 Information Stay Home - Stay Safe - Save Lives DZONGKHAG Hotline # Dzongda Incident Commander Eastern COVID-19 Task Force Coordination Office (ECCO) It will undo everything that we have achieved so far. “ A careless person’s mistake will undo all our efforts. TRASHI YANGTSE Name Contact # Zone (Yangtse) Delivery time Delivery Day Order Day Rigney (Rigney including Hospital, RNR, NSC, BOD, 17641121 NRDCL ) 8:00 AM to 12:00 17834589/77218 PM 454 Baechen SATURDAY Retailers 17509633 SUNDAY ( 7:00 AM to 17691083 Main Town (below Dzong and Choeten Kora 12:00 PM to 3:00 6:00 PM) 17818250 area) PM 17282463 Baylling (above Dzong, including Rinchengang till 3:00 PM to 6:00 17699183 BCS) PM 6:00 AM to 17696122 Baylling, Baechen, Rigney and Main Town THURSDAY Vendors 5:00PM ( SATURDAY 6:00 AM to 6:00 Agriculture 6:00 AM to 17302242 From Serkhang Chu till Choeten Kora PM) 5:00PM 6:00 AM to MONDAY 17874349 Rigney & Baechen Zone (Yangtse and Doksum) THURSDAY Yangtse Vendors 5:00PM WEDNESDAY & SATURDAY ( Jomotshangkha Drungkhag -1210 Nganglam Drungkhag - 1195 Samdrupcholing Drungkhkag - 1191 Livestock 6:00 AM to 6:00 AM to 6:00 17532906 Main Town & Baylling Zone PM) 5:00PM TUESDAY & 77885806/77301 2:00 PM to 5:00 LPG Delivery Yangtse Throm TUESDAY & FRIDAY FRIDAY ( 9:00 AM 070 PM to 1:00 PM) Order & Delivery Schedule 17500690 FRIDAY ( Meat Shop Yangtse Throm 7:00 AM to 1:00PM SATURDAY 6:00 AM to 6:00 77624407 PM) Pharmacy 17988376 Doksum & Yangtse Throm As & when As & When / # 3 9 1 3 3 1 3 9 8 9 0 1 6 7 2 8 5 3 6 9 3 8 3 6 8 5 8 2 4 8 5 2 7 t 5 0 7 5 6 0 4 6 5 4 4 1 5 0 8 5 1 2 1 5 c 7 8 9 2 5 9 3 9 4 9 4 6 2 1 7 7 8 8 1 3 a 5 5 0 7 4 2 4 t 0 3 9 5 7 8 9 9 0 6 1 4 8 7 8 5 6 5 3 7 n 5 8 6 6 3 2 6 5 5 8 8 6 8 8 4 4 8 9 5 8 o 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 6 7 7 7 7 7 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 C 1 . -

World Bank Document

Small Area Estimation of Poverty in Bhutan Poverty Mapping Report 2017 Public Disclosure Authorized National Statistics Bureau, Bhutan Poverty and Equity Global Practice, The World Bank Public Disclosure Authorized December 2019 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Acknowledgements: This report and the poverty map estimation was authored by Dung Doan (Consultant, The World Bank), in collaboration with the National Statistics Bureau (NSB) of Bhutan. The preparation of the report was led by Yeon Soo Kim (Economist, The World Bank). Benu Bidani (Practice Manger, The World Bank) and Chhime Tshering (Director, NSB) provided overall guidance to the team. Helpful comments and technical guidance were provided by Minh Cong Nguyen (Senior Data Scientist, The World Bank) and Paul Andres Corral Rodas (Data Scientist, The World Bank) and are gratefully acknowledged. Abbreviations BIC Bayesian Information Criterion BLSS Bhutan Living Standards Survey PHCB Population and Housing Census of Bhutan CI Confidence Interval GNHC Gross National Happiness Commission NSB National Statistics Bureau SE Standard Error SD Standard Deviation I. Introduction Bhutan has made great strides in reducing poverty over the last decade. The official national poverty rate declined from 23.2 percent in 2007 to 8.2 percent in 2017; most of this improvement came from rural areas with rural poverty decreasing from 30.9 to 11.9 percent during this period. This is particularly remarkable given a largely agrarian economy and the challenges arising from sparse population settlement patterns. However, there are large differences in poverty levels across Dzongkhags. A good understanding of the geographic distribution of poverty is of great importance to guide policies to realize Gross National Happiness – Bhutan’s development philosophy that emphasizes a holistic and inclusive approach to sustainable development. -

Geographical and Historical Background of Education in Bhutan

Chapter 2 Geographical and Historical Background of Education in Bhutan Geographical Background There is a great debate regarding from where the name of „Bhutan‟ appears. In old Tibetan chronicles Bhutan was called Mon-Yul (Land of the Mon). Another theory explaining the origin of the name „Bhutan‟ is derived from Sanskrit „Bhotanta‟ where Tibet was referred to as „Bhota‟ and „anta‟ means end i. e. the geographical area at the end of Tibet.1 Another possible explanation again derived from Sanskrit could be Bhu-uttan standing for highland, which of course it is.2 Some scholars think that the name „Bhutan‟ has come from Bhota (Bod) which means Tibet and „tan‟, a corruption of stan as found in Indo-Persian names such as „Hindustan‟, „Baluchistan‟ and „Afganistan‟etc.3 Another explanation is that “It seems quite likely that the name „Bhutan‟ has come from the word „Bhotanam‟(Desah iti Sesah) i.e., the land of the Bhotas much the same way as the name „Iran‟ came from „Aryanam‟(Desah), Rajputana came from „Rajputanam‟, and „Gandoana‟ came from „Gandakanam‟. Thus literally „Bhutan‟ means the land of the „Bhotas‟-people speaking a Tibetan dialect.”4 But according to Bhutanese scholars like Lopen Nado and Lopen Pemala, Bhutan is called Lho Mon or land of the south i.e. south of Tibet.5 However, the Bhutanese themselves prefer to use the term Drukyul- the land of Thunder Dragon, a name originating from the word Druk meaning „thunder dragon‟, which in turn is derived from Drukpa school of Tibetan Buddhism. Bhutan presents a striking example of how the geographical setting of a country influences social, economic and political life of the people. -

Bhutan's Accelerating Urbanization

Document of The World Bank Public Disclosure Authorized Report No.: 62072 Public Disclosure Authorized PROJECT PERFORMANCE ASSESSMENT REPORT KINGDOM OF BHUTAN URBAN DEVELOPMENT PROJECT (CREDIT 3310) June 13, 2011 Public Disclosure Authorized IEG Public Sector Evaluation Independent Evaluation Group Public Disclosure Authorized Currency Equivalents (annual averages) Currency Unit = Bhutanese Ngultrum (Nu) 1999 US$1.00 Nu 43.06 2000 US$1.00 Nu 44.94 2001 US$1.00 Nu 47.19 2002 US$1.00 Nu 48.61 2003 US$1.00 Nu 46.58 2004 US$1.00 Nu 45.32 2005 US$1.00 Nu 44.10 2006 US$1.00 Nu 45.31 2007 US$1.00 Nu 41.35 2006 US$1.00 Nu 43.51 2007 US$1.00 Nu 48.41 Abbreviations and Acronyms ADB Asian Development Bank BNUS Bhutan National Urbanization Strategy CAS Country Assistance Strategy CPS Country Partnership Strategy DANIDA Danish International Development Agency DUDES Department of Urban Development and Engineering Services (of MOWHS) GLOF Glacial Lake Outburst Flood ICR Implementation Completion Report IEG Independent Evaluation Group IEGWB Independent Evaluation Group (World Bank) MOF Ministry of Finance MOWHS Ministry of Works & Human Settlement PPAR Project Performance Assessment Report RGOB Royal Government of Bhutan TA Technical Assistance Fiscal Year Government: July 1 – June 30 Director-General, Independent Evaluation : Mr. Vinod Thomas Director, IEG Public Sector Evaluation : Ms. Monika Huppi (Acting) Manager, IEG Public Sector Evaluation : Ms. Monika Huppi Task Manager : Mr. Roy Gilbert i Contents Principal Ratings ............................................................................................................... -

Gross National Happiness Commission the Royal Government of Bhutan

STRATEGIC PROGRAMME FOR CLIMATE RESILIENCE (SPCR) UNDER THE PILOT PROGRAMME FOR CLIMATE RESILIENCE (PPCR) Climate-Resilient & Low-Carbon Sustainable Development Toward Maximizing the Royal Government of Bhutan’s Gross National Happiness GROSS NATIONAL HAPPINESS COMMISSION THE ROYAL GOVERNMENT OF BHUTAN FOREWORD The Royal Government of Bhutan (RGoB) recognizes the devastating impact that climate change is having on Bhutan’s economy and our vulnerable communities and biosphere, and we are committed to address these challenges and opportunities through the 12th Five Year Plan (2018-2023). In this context, during the 2009 Conference of the Parties 15 (COP 15) in Copenhagen, RGoB pledged to remain a carbon-neutral country, and has successfully done so. This was reaffirmed at the COP 21 in Paris in 2015. Despite being a negative-emission Least Developed Country (LDC), Bhutan continues to restrain its socioeconomic development to maintain more than 71% of its geographical area under forest cover,1 and currently more than 50% of the total land area is formally under protected areas2, biological corridors and natural reserves. In fact, our constitutional mandate declares that at least 60% of Bhutan’s total land areas shall remain under forest cover at all times. This Strategic Program for Climate Resilience (SPCR) represents a solid framework to build the climate- resilience of vulnerable sectors of the economy and at-risk communities across the country responding to the priorities of NDC. It also offers an integrated story line on Bhutan’s national -

Royal Government of Bhutan Ministry of Finance

ROYAL GOVERNMENT OF BHUTAN MINISTRY OF FINANCE COMPENSATION RATES - 2017 DEPARTMENT OF NATIONAL PROPERTIES PROPERTY ASSESSMENT AND VALUATION AGENCY C O N T E N T S Sl. No. P A R T I C U L A R S Page No. 1. A – Rural Land Compensation Rates 2017 a) Kamzhing (Dry Land) 1 b) Chhuzhing (Wet land) 2 c) Ngultho Dumra (Cash Crop Land) 3 d) Class A1(Land close to Thromde) 4 2. Factors determining Rural Land Compensation 5 3. B – Urban Land Compensation Rates 2017 a) Thimphu Thromde 6 b) Phuntsholing Thromde 7 c) Gelephu Thromde 8 d) Samdrup Jongkhar Thromde 9 e) Samtse Thromde 10 f) Damphu Throm de 11 g) Rest of the Dzongkhag Thromdes 12 h) Yenlag Thromdes 13 i) Sarpang Yenlag Thromde 14 j) Duksum Yenlag Thromde 15 k) Specific Towns 15 4. Factors determining Urban Land Compensation 15 5. Guideline on Compensation rate for building 16 6. Implementation Procedure 16 7. C – Agricultural Compensation Rates 2017 a. Compensation Rates for Fruit Trees 17 b. Compensation Rate for Developed Pasture 18 c. Compensation Rate for Fodder Trees 18 d. Land Development Cost of Chhuzhing 18 e. Formula for working out Compensation of Forest Trees 18 8. Format for Rural Land Valuation 19 9. Format for Urban Land Valuation 20 ROYAL GOVERNMENT OF BHUTAN MINISTRY OF FINANCE Department of National Properties Property Assessment & Valuation Agency A - Rural Land Compensation Rates 2017 (a) For Rural Kamzhing Land Amount Nu./decimal Sl. No. Dzongkhag Class A Class B Class C 1 Bumthang 9,130.90 6,391.63 3,852.13 2 Chhukha 6,916.18 4,841.33 3,112.89 3 Dagana 5,538.22 3,876.75 -

"First Report on the State of the World's Animal Genetic Resources"

Country Report of Australia for the FAO First Report on the State of the World’s Animal Genetic Resources 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY................................................................................................................5 CHAPTER 1 ASSESSING THE STATE OF AGRICULTURAL BIODIVERSITY THE FARM ANIMAL SECTOR IN AUSTRALIA.................................................................................7 1.1 OVERVIEW OF AUSTRALIAN AGRICULTURE, ANIMAL PRODUCTION SYSTEMS AND RELATED ANIMAL BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY. ......................................................................................................7 Australian Agriculture - general context .....................................................................................7 Australia's agricultural sector: production systems, diversity and outputs.................................8 Australian livestock production ...................................................................................................9 1.2 ASSESSING THE STATE OF CONSERVATION OF FARM ANIMAL BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY..............10 Major agricultural species in Australia.....................................................................................10 Conservation status of important agricultural species in Australia..........................................11 Characterisation and information systems ................................................................................12 1.3 ASSESSING THE STATE OF UTILISATION OF FARM ANIMAL GENETIC RESOURCES IN AUSTRALIA. ........................................................................................................................................................12 -

Continuing Customs of Negotiation and Contestation in Bhutan

Continuing Customs of Negotiation and Contestation in Bhutan Adam Pain and Deki Pema∗∗ Introduction A concern for the maintenance of traditional values and customs in the processes of modernisation within Bhutan is evident in much of Bhutan’s official documentation. The fundamental importance given to the maintenance and fostering of Buddhism, its beliefs and associated institutions reflected in Bhutan’s rich culture, is constantly returned to and emphasized in commentary. Thus the establishment of the Special Commission for Cultural Affairs in 1985 “is seen as a reflection of the great importance placed upon the preservation of the country’s unique and distinct religious and cultural traditions and values, expressed in the customs, manners, language, dress, arts and crafts which collectively define Bhutan’s national identity” (Ministry of Planning, 1996, p.193). Equally the publication of a manual on Bhutanese Etiquette (Driglam Namzhag) by the National Library of Bhutan was hopeful that it “would serve as a significant foundation in the process of cultural preservation and cultural synthesis” (Publishers Forward, National Library, 1999). One strand of analysis that could be pursued concerns the very construct of “traditional” and what is constituted as “within” or “without” that tradition. As Hobsbawm (1983) reminds us with respect to the British Monarchy, much of the ceremonial associated with it is of recent origin. Equally national flags, national anthems and even the nation state, are, as Hobsbawm would have it, “ invented traditions” designed largely to “ inculcate certain values and norms of behaviour by repetition, which automatically implies continuity with ∗ Research Fellow, School of Development Studies, University of East Anglia & Planning Officer, Policy & Planning Division, Ministry of Agriculture, Thimphu 219 Continuing Customs of Negotiation and Contestation in Bhutan the past” (op. -

Population and Migration in Thimphu Thromde

Population and Migration in Thimphu Thromde Sangay Chophel* Abstract As a developing country, Bhutan is on the upward trajectory of urbanization. While it has benefits it also exerts pressures. Within Bhutan, Thimphu thromde has the largest urban population, which exhibit many forms of urbanization. Using the data from 2017 Population and Housing Census of Bhutan, the paper projects the population of Thimphu city till 2027 due to lack of its population projection. The cohort-component method is used for projection. The net-migration from 2005 to 2017 is calculated using residual method. Further, employing probit regression, the determinants of migration to Thimphu thromde is examined. Age, marriage, unemployment, land, household composition, household income and education are significant determinants of migration. Introduction Urbanization in Bhutan has continued apace. The urban population has increased from 30.9% in 2005 to 37.8% in 2017, and largest share of the overall population reside in Thimphu thromde (city) at 15.8%1 where most of the government offices are based. The other three cities are Phuntsholing, Samdrup Jongkhar and Gelephu thromdes. There are relatively smaller urban areas in each of the 20 districts. The annual growth rate of Thimphu thromde (3.72%) has * Senior Research Officer, Centre for Bhutan & GNH Studies. Email: [email protected], [email protected] 1 See the report of the first census conducted in 2005, Population and Housing Census of Bhutan 2005, and the second census conducted in 2017, 2017 Population and Housing Census of Bhutan. 114 Population and Migration in Thimphu Thromde outpaced the national population growth rate (1.3%) as it is evident from the last two censuses. -

Final Report APL Project 2017/2217

Review of the scientific literature and the international pig welfare codes and standards to underpin the future Standards and Guidelines for Pigs Final Report APL Project 2017/2217 August 2018 Animal Welfare Science Centre, University of Melbourne Dr Lauren Hemsworth Prof Paul Hemsworth Ms Rutu Acharya Mr Jeremy Skuse 21 Bedford St North Melbourne, VIC 3051 1 Disclaimer: APL shall not be responsible in any manner whatsoever to any person who relies, in whole or in part, on the contents of this report unless authorised in writing by the Chief Executive Officer of APL. Table of Contents Executive Summary .................................................................................................................... 3 1. Animal welfare and its assessment ...................................................................................... 12 2. Purpose of this Review and the Australian Model Code of Practice for the Welfare of Animals – Pigs .......................................................................................................................... 19 3. Housing and management of pigs ....................................................................................... 22 3.1 Gestating sows (including gilts) ......................................................................................... 23 3.2 Farrowing/lactating sow and piglets, including painful husbandry practices ................... 35 3.3 Weaner and growing-finishing pigs .................................................................................. -

Road Network Project II

Resettlement Planning Document Resettlement Plan for Raidak-Lhamoizingkha Section Document Stage: Draft Project Number: 39225 July 2009 Bhutan: Road Network Project II Prepared by Department of Roads, Ministry of Works and Human Settlement. The resettlement plan is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. CONTENTS Page EXECUTIVE SUMMARY i I. THE PROJECT BACKGROUND 1 A. Project Description 1 B. Subproject Benefits and Impacts 1 C. Measures to Minimize Impact 1 D. Scope and Objectives of the Resettlement Plan (RP) 2 II. SOCIAL PROFILE OF SUBPROJECT AREA 3 A. Socioeconomic Survey and Methodology 3 B. Social Profile of Affected Persons (APs) 3 C. Economic Activities/ Livelihood 3 D. Religion 4 E. Education and Health 4 F. Drinking Water 4 G. Gender Analysis 5 III. SCOPE OF LAND ACQUISITION AND RESETTLEMENT IMPACTS 5 A. Types of loss and ownership 5 B. Subproject Impacts 6 C. Properties Affected 7 D. Options of Relocation 7 IV. RESETTLEMENT POLICY, LEGAL FRAMEWORK AND ENTITLEMENT MATRIX 7 A. Objective 7 B. Existing Bhutanese Law 7 C. Resettlement Principles for the Project 8 V. PUBLIC CONSULTATION AND DISCLOSURE OF INFORMATION 15 A. Methods of Public Consultation 15 B. Scope of Consultation and Issues 15 C. Major Findings of the Consultations 16 D. Plan for Further Consultation in the Subproject 17 E. Disclosure of RP 18 VI. INSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORK 18 A. Institutional Requirement 18 B. Resettlement Management 18 C. Grievance Redressal Mechanism 19 VII. RESETTLEMENT BUDGET AND FINANCING 20 VIII. -

6 Dzongs of Bhutan - Architecture and Significance of These Fortresses

6 Dzongs of Bhutan - Architecture and Significance of These Fortresses Nestled in the great Himalayas, Bhutan has long been the significance of happiness and peace. The first things that come to one's mind when talking about Bhutan are probably the architectures, the closeness to nature and its strong association with the Buddhist culture. And it is just to say that a huge part of the country's architecture has a strong Buddhist influence. One such distinctive architecture that you will see all around Bhutan are the Dzongs, they are beautiful and hold a very important religious position in the country. Let's talk more about the Dzongs in Bhutan. What are the Bhutanese Dzongs? Wangdue Phodrang Dzong in Bhutan (Source) Dzongs can be literally translated to fortress and they represent the majestic fortresses that adorn every corner of Bhutan. Dzong are generally a representation of victory and power when they were built in ancient times to represent the stronghold of Buddhism. They also represent the principal seat for Buddhist school responsible for propagating the ideas of the religion. Importance of Dzongs in Bhutan Rinpung Dzong in Paro, home to the government administrative offices and monastic body of the district (Source) The dzongs in Bhutan serve several purposes. The two main purposes that these dzongs serve are administrative and religious purposes. A part of the building is dedicated for the administrative purposes and a part of the building to the monks for religious purposes. Generally, this distinction is made within the same room from where both administrative and religious activities are conducted.