Biodiversity of Pig Breeds from China and Europe Estimated from Pooled DNA Samples: Differences in Microsatellite Variation Between Two Areas of Domestication

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"First Report on the State of the World's Animal Genetic Resources"

Country Report of Australia for the FAO First Report on the State of the World’s Animal Genetic Resources 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY................................................................................................................5 CHAPTER 1 ASSESSING THE STATE OF AGRICULTURAL BIODIVERSITY THE FARM ANIMAL SECTOR IN AUSTRALIA.................................................................................7 1.1 OVERVIEW OF AUSTRALIAN AGRICULTURE, ANIMAL PRODUCTION SYSTEMS AND RELATED ANIMAL BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY. ......................................................................................................7 Australian Agriculture - general context .....................................................................................7 Australia's agricultural sector: production systems, diversity and outputs.................................8 Australian livestock production ...................................................................................................9 1.2 ASSESSING THE STATE OF CONSERVATION OF FARM ANIMAL BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY..............10 Major agricultural species in Australia.....................................................................................10 Conservation status of important agricultural species in Australia..........................................11 Characterisation and information systems ................................................................................12 1.3 ASSESSING THE STATE OF UTILISATION OF FARM ANIMAL GENETIC RESOURCES IN AUSTRALIA. ........................................................................................................................................................12 -

Final Report APL Project 2017/2217

Review of the scientific literature and the international pig welfare codes and standards to underpin the future Standards and Guidelines for Pigs Final Report APL Project 2017/2217 August 2018 Animal Welfare Science Centre, University of Melbourne Dr Lauren Hemsworth Prof Paul Hemsworth Ms Rutu Acharya Mr Jeremy Skuse 21 Bedford St North Melbourne, VIC 3051 1 Disclaimer: APL shall not be responsible in any manner whatsoever to any person who relies, in whole or in part, on the contents of this report unless authorised in writing by the Chief Executive Officer of APL. Table of Contents Executive Summary .................................................................................................................... 3 1. Animal welfare and its assessment ...................................................................................... 12 2. Purpose of this Review and the Australian Model Code of Practice for the Welfare of Animals – Pigs .......................................................................................................................... 19 3. Housing and management of pigs ....................................................................................... 22 3.1 Gestating sows (including gilts) ......................................................................................... 23 3.2 Farrowing/lactating sow and piglets, including painful husbandry practices ................... 35 3.3 Weaner and growing-finishing pigs .................................................................................. -

Farming and Biodiversity of Pigs in Bhutan

Animal Genetic Resources, 2011, 48, 47–61. © Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2011 doi:10.1017/S2078633610001256 Farming and biodiversity of pigs in Bhutan K. Nidup1,2, D. Tshering3, S. Wangdi4, C. Gyeltshen5, T. Phuntsho5 and C. Moran1 1Centre for Advanced Technologies in Animal Genetics and Reproduction (REPROGEN), Faculty of Veterinary Science, University of Sydney, Australia; 2College of Natural Resources, Royal University of Bhutan, Lobesa, Bhutan; 3Department of Livestock, National Pig Breeding Centre, Ministry of Agriculture, Thimphu, Bhutan; 4Department of Livestock, Regional Pig and Poultry Breeding Centre, Ministry of Agriculture, Lingmithang, Bhutan; 5Department of Livestock, Regional Pig and Poultry Breeding Centre, Ministry of Agriculture, Gelephu, Bhutan Summary Pigs have socio-economic and cultural importance to the livelihood of many Bhutanese rural communities. While there is evidence of increased religious disapproval of pig raising, the consumption of pork, which is mainly met from imports, is increasing every year. Pig development activities are mainly focused on introduction of exotic germplasm. There is an evidence of a slow but steady increase in the population of improved pigs in the country. On the other hand, indigenous pigs still comprise 68 percent of the total pig population but their numbers are rapidly declining. If this trend continues, indigenous pigs will become extinct within the next 10 years. Once lost, this important genetic resource is largely irreplaceable. Therefore, Government of Bhutan must make an effort to protect, promote and utilize indigenous pig resources in a sustainable manner. In addition to the current ex situ conservation programme based on cryopre- servation of semen, which needs strengthening, in situ conservation and a nucleus farm is required to combat the enormous decline of the population of indigenous pigs and to ensure a sustainable source of swine genetic resources in the country. -

Gwartheg Prydeinig Prin (Ba R) Cattle - Gwartheg

GWARTHEG PRYDEINIG PRIN (BA R) CATTLE - GWARTHEG Aberdeen Angus (Original Population) – Aberdeen Angus (Poblogaeth Wreiddiol) Belted Galloway – Belted Galloway British White – Gwyn Prydeinig Chillingham – Chillingham Dairy Shorthorn (Original Population) – Byrgorn Godro (Poblogaeth Wreiddiol). Galloway (including Black, Red and Dun) – Galloway (gan gynnwys Du, Coch a Llwyd) Gloucester – Gloucester Guernsey - Guernsey Hereford Traditional (Original Population) – Henffordd Traddodiadol (Poblogaeth Wreiddiol) Highland - Yr Ucheldir Irish Moiled – Moel Iwerddon Lincoln Red – Lincoln Red Lincoln Red (Original Population) – Lincoln Red (Poblogaeth Wreiddiol) Northern Dairy Shorthorn – Byrgorn Godro Gogledd Lloegr Red Poll – Red Poll Shetland - Shetland Vaynol –Vaynol White Galloway – Galloway Gwyn White Park – Gwartheg Parc Gwyn Whitebred Shorthorn – Byrgorn Gwyn Version 2, February 2020 SHEEP - DEFAID Balwen - Balwen Border Leicester – Border Leicester Boreray - Boreray Cambridge - Cambridge Castlemilk Moorit – Castlemilk Moorit Clun Forest - Fforest Clun Cotswold - Cotswold Derbyshire Gritstone – Derbyshire Gritstone Devon & Cornwall Longwool – Devon & Cornwall Longwool Devon Closewool - Devon Closewool Dorset Down - Dorset Down Dorset Horn - Dorset Horn Greyface Dartmoor - Greyface Dartmoor Hill Radnor – Bryniau Maesyfed Leicester Longwool - Leicester Longwool Lincoln Longwool - Lincoln Longwool Llanwenog - Llanwenog Lonk - Lonk Manx Loaghtan – Loaghtan Ynys Manaw Norfolk Horn - Norfolk Horn North Ronaldsay / Orkney - North Ronaldsay / Orkney Oxford Down - Oxford Down Portland - Portland Shropshire - Shropshire Soay - Soay Version 2, February 2020 Teeswater - Teeswater Wensleydale – Wensleydale White Face Dartmoor – White Face Dartmoor Whitefaced Woodland - Whitefaced Woodland Yn ogystal, mae’r bridiau defaid canlynol yn cael eu hystyried fel rhai wedi’u hynysu’n ddaearyddol. Nid ydynt wedi’u cynnwys yn y rhestr o fridiau prin ond byddwn yn eu hychwanegu os bydd nifer y mamogiaid magu’n cwympo o dan y trothwy. -

First Report on the State of the World's Animal Genetic Resources"

"First Report on the State of the World’s Animal Genetic Resources" (SoWAnGR) Country Report of the United Kingdom to the FAO Prepared by the National Consultative Committee appointed by the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra). Contents: Executive Summary List of NCC Members 1 Assessing the state of agricultural biodiversity in the farm animal sector in the UK 1.1. Overview of UK agriculture. 1.2. Assessing the state of conservation of farm animal biological diversity. 1.3. Assessing the state of utilisation of farm animal genetic resources. 1.4. Identifying the major features and critical areas of AnGR conservation and utilisation. 1.5. Assessment of Animal Genetic Resources in the UK’s Overseas Territories 2. Analysing the changing demands on national livestock production & their implications for future national policies, strategies & programmes related to AnGR. 2.1. Reviewing past policies, strategies, programmes and management practices (as related to AnGR). 2.2. Analysing future demands and trends. 2.3. Discussion of alternative strategies in the conservation, use and development of AnGR. 2.4. Outlining future national policy, strategy and management plans for the conservation, use and development of AnGR. 3. Reviewing the state of national capacities & assessing future capacity building requirements. 3.1. Assessment of national capacities 4. Identifying national priorities for the conservation and utilisation of AnGR. 4.1. National cross-cutting priorities 4.2. National priorities among animal species, breeds, -

British Experience of A. I. and Its Use in the Conservation of Rare Pig Breeds J

BRITISH EXPERIENCE OF A. I. AND ITS USE IN THE CONSERVATION OF RARE PIG BREEDS J. R. Walters and P. N. Hooper Masterbreeders (Livestock Development) Ltd. Hastoe, Tring, Herts. HP23 6PJ. UK. SUMMARY There are seven endangered pig breeds in Britain being conserved by a semen freezing programme financed by the Rare Breeds Survival Trust. To date, 22 boars have been frozen with satisfactory semen parameters. Where- ever possible fresh semen is also made available to breeders and data from 14 boars suggest similar semen parameters to the main white breeds. However significant numbers of rare breed boars show low libido. On average. Prostaglandin F2«C is used twice as often in rare breeds. On limited observations, the Berkshire and Large Black breeds appear most affected. INTRODUCTION In Great Britain endangered pig breeds are maintained mostly in small groups (maximum of 2 boars and 15 females) on a variety of farms. The major problem with this is the avoidance of inbreeding and genetic drift. Smith (1984) and Maijala et al (1984) have outlined the suitability of rotational systems of breeding to minimise inbreeding as long as numbers are adequate. However, of the seven British breeds listed with the Rare Breeds Survival Trust (RBST), six are category one (critical) and only one - Gloucester Old Spot - category two (rare). Although there has been an increase in litter notifications and herd book registrations in most breeds over the past five years, there remains concern over the future of the breeds, particularly as in some breeds more than 50% of litters are cross bred. -

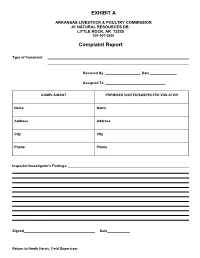

Complaint Report

EXHIBIT A ARKANSAS LIVESTOCK & POULTRY COMMISSION #1 NATURAL RESOURCES DR. LITTLE ROCK, AR 72205 501-907-2400 Complaint Report Type of Complaint Received By Date Assigned To COMPLAINANT PREMISES VISITED/SUSPECTED VIOLATOR Name Name Address Address City City Phone Phone Inspector/Investigator's Findings: Signed Date Return to Heath Harris, Field Supervisor DP-7/DP-46 SPECIAL MATERIALS & MARKETPLACE SAMPLE REPORT ARKANSAS STATE PLANT BOARD Pesticide Division #1 Natural Resources Drive Little Rock, Arkansas 72205 Insp. # Case # Lab # DATE: Sampled: Received: Reported: Sampled At Address GPS Coordinates: N W This block to be used for Marketplace Samples only Manufacturer Address City/State/Zip Brand Name: EPA Reg. #: EPA Est. #: Lot #: Container Type: # on Hand Wt./Size #Sampled Circle appropriate description: [Non-Slurry Liquid] [Slurry Liquid] [Dust] [Granular] [Other] Other Sample Soil Vegetation (describe) Description: (Place check in Water Clothing (describe) appropriate square) Use Dilution Other (describe) Formulation Dilution Rate as mixed Analysis Requested: (Use common pesticide name) Guarantee in Tank (if use dilution) Chain of Custody Date Received by (Received for Lab) Inspector Name Inspector (Print) Signature Check box if Dealer desires copy of completed analysis 9 ARKANSAS LIVESTOCK AND POULTRY COMMISSION #1 Natural Resources Drive Little Rock, Arkansas 72205 (501) 225-1598 REPORT ON FLEA MARKETS OR SALES CHECKED Poultry to be tested for pullorum typhoid are: exotic chickens, upland birds (chickens, pheasants, pea fowl, and backyard chickens). Must be identified with a leg band, wing band, or tattoo. Exemptions are those from a certified free NPIP flock or 90-day certificate test for pullorum typhoid. Water fowl need not test for pullorum typhoid unless they originate from out of state. -

ACE Appendix

CBP and Trade Automated Interface Requirements Appendix: PGA August 13, 2021 Pub # 0875-0419 Contents Table of Changes .................................................................................................................................................... 4 PG01 – Agency Program Codes ........................................................................................................................... 18 PG01 – Government Agency Processing Codes ................................................................................................... 22 PG01 – Electronic Image Submitted Codes .......................................................................................................... 26 PG01 – Globally Unique Product Identification Code Qualifiers ........................................................................ 26 PG01 – Correction Indicators* ............................................................................................................................. 26 PG02 – Product Code Qualifiers ........................................................................................................................... 28 PG04 – Units of Measure ...................................................................................................................................... 30 PG05 – Scientific Species Code ........................................................................................................................... 31 PG05 – FWS Wildlife Description Codes ........................................................................................................... -

Selected Readings on the History and Use of Old Livestock Breeds

NATIONAL AGRICULTURAL LIBRARY ARCHIVED FILE Archived files are provided for reference purposes only. This file was current when produced, but is no longer maintained and may now be outdated. Content may not appear in full or in its original format. All links external to the document have been deactivated. For additional information, see http://pubs.nal.usda.gov. Selected Readings on the History and Use of Old Livestock Breeds United States Department of Agriculture Selected Readings on the History and Use of Old Livestock Breeds National Agricultural Library September 1991 Animal Welfare Information Center By: Jean Larson Janice Swanson D'Anna Berry Cynthia Smith Animal Welfare Information Center National Agricultural Library U.S. Department of Agriculture And American Minor Breeds Conservancy P.O. Box 477 Pittboro, NC 27312 Acknowledgement: Jennifer Carter for computer and technical support. Published by: U. S. Department of Agriculture National Agricultural Library Animal Welfare Information Center Beltsville, Maryland 20705 Contact us: http://awic.nal.usda.gov/contact-us Web site: www.nal.usda.gov/awic Published in cooperation with the Virginia-Maryland Regional College of Veterinary Medicine Policies and Links Introduction minorbreeds.htm[1/15/2015 2:16:51 PM] Selected Readings on the History and Use of Old Livestock Breeds For centuries animals have worked with and for people. Cattle, goats, sheep, pigs, poultry and other livestock have been an essential part of agriculture and our history as a nation. With the change of agriculture from a way of life to a successful industry, we are losing our agricultural roots. Although we descend from a nation of farmers, few of us can name more than a handful of livestock breeds that are important to our production of food and fiber. -

Montana Farmer-Stockman Reaches REGISTERED HAMPSHIRE Rams for Sale—Jim Good Home

■ I s r ■ a m. E APPALOOSAS & P.O.A.s, Stud Prospects, 4-H WESTERN MONTANA—$25,000 down payment colts. Fillies and mares. Cecil Bilbre, Choteau, buys beautiful ranch including 200 top Hereford O I o e Montana. Phone 466-2246. _____________ cows, full line machinery, 800 tons hay, supplies and tools. Owner retiring—will leave his capi 4 I ONE “SHETLAND STALLION, registered. Cres j cent Breeding—gentle. Hazel French, Route 1, tal invested in the ranch. Location incomparable —within walking distance of grade and high Lewistown. Montana. _________________________ schools. Easy operation—good fall and winter i •BUYING SHEEP ___________ grazing. Private (free) water rights. Very low a/Cs, jot CHOICE PUREBRED HAMPSHIRE rams for taxes. Two modern homes. Heavy calves. This I •SELLING sale, lambs and yearlings. Mt. Haggin Breeding. is a top outfit. FISHER REALTY, Phone 745- Harry Miller, Star Route, Bozeman. Montana. 3101. St. Ignatius. Montana._______________________ K TOP GROCERY $200,000 volume. 175 acre river 3 FOR SALE—70 head ewes, 2 to 4 years old, •TRADING bottom, sprinkler system, business machines- $15.00 per head. Andrew Teterud, Dixon, Mon ; I tana. Phone 726-3126. __________________________________ office furniture, a money maker. Exclusive mu i sic store. Motel priced low. 40 acre river front, The rate is very low for our big circulation. Montana Farmer-Stockman reaches REGISTERED HAMPSHIRE rams for sale—Jim good home. 540 acre wheat farm, creek, modern I nearly nine out of every ten farm and ranch families in Montana with additional Moore, Rt. No. 2, Belgrade, Montana. Phone home. -

A Newsletter from Marcus Oldham College Old Students Association

A ne wsle tter from M arcus y 2012 Oldham C Januar ollege Old S • Issue 1 • tudents Association Volume 19 A ne wsl etter from Marcus 2012 Oldham January College Old Issue 1 • Students Association Volume 19 • The Principal’s Perspective y the time this edition of MOCOSA goes to print promote and implement sound economic strategies to improve and is distributed, the 2011 graduation will be over the quality of life of people in their areas. Time was spent with and another group of graduates will have entered local councils seeing how communities develop their capacity to B create a prosperous and sustainable future through co-ordination, the workforce. A real strength of the College is the large number of alumni who go on to be successful ambassadors collaboration and effective use of public and private resources. in their chosen field of endeavour. The success of Marcus My objective in visiting these establishments was to learn what I Oldham as an institution is the result, in part, of the efforts could about rural entrepreneurialism, what it is and what makes and high profile of our achieving alumni. for success, and to bring that knowledge back to Marcus Oldham College for further development among our students. Australia During the year the College made submissions to both the has a proud record of agricultural and equine achievement Victorian State and the Federal Inquiries into agricultural education through entrepreneurialism, even if we don’t call it that. and workforce planning. These Inquiries will endeavour to identify the reasons why agricultural enrolments are declining Whilst in the United States, I reflected on the work of a leading nationally and why more young people are not pursuing careers educator and researcher, Professor Ron Ritchhart, who holds in agriculture. -

September, 1936 . Club Series No. 10 LIVESTOCK JUDGING for 4-H CLUB MEMBERS (A Revision of Extension Circular No. 131) NORTH

September, 1936 . Club Series No. 10 LIVESTOCK JUDGING FOR 4-H CLUB MEMBERS (A revision of Extension Circular No. 131) NORTH CAROLINA STATE COLLEGE OF AGRICULTURE AND ENGINEERING AND U. 5. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE. CO-OPERATING NORTH CAROLINA AGRICULTURAL EXTENSION SERVICE I. O. SCHAUB. DIRECTOR STATE COLLEGE STATION RALEIGH, NORTH CAROLINA DISTRIBUTED IN FURTHERANCE OF THE ACTS OF CONGRESS OF MAY 8 AND JUNE 30, 1914 LIVESTOCK JUDGING FOR 4-H CLUB MEMBERS INTRODUCTION Because of its value in teaching the fundamental facts regard- ing the types, characteristics and functions of farm animals, Livestock Judging is considered a definite part of our 4-H Live- stock projects. To make this a more valuable project this bulletin has been prepared. It represents the best thought and the most accurate information available, and has been assembled in a form understandable to farm boys and girls. Every farm boy and girl should be a good judge of livestock. North Carolina needs more and better livestock in order to have a more profitable system of agriculture; to maintain soil fertility; and to supply the necessary food and feed supply for man and animals. Good livestock is essential to a profitable program of agriculture. A correct knowledge of good livestock is a prerequisite to good livestock. Therefore it is our hope that through 4-H livestock projects and especially through livestock judging that the 4-H Club Member will learn to recognize the good? as well as the undesirable types and characteristics of live- stockand that as a result of this training and information North Carelina will have more and better livestock.