James Adams of Springfield, Illinois 33

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Lincoln Bibles”?

How Many “Lincoln Bibles”? GORDON LEIDNER In a 1940 edition of Lincoln Lore, editor and historian Dr. Louis A. War- ren stated that “no book could be more appropriately associated with Abraham Lincoln than the Bible,” and he briefly introduced his read- ers to nine “Historic Lincoln Bibles” that he thought should be linked with the sixteenth president.1 Eleven years later, Robert S. Barton, son of the Lincoln biographer Rev. William E. Barton, published a paper titled “How Many Lincoln Bibles?”2 In it, Barton updated the status of Warren’s nine historic Lincoln Bibles, then added three Bibles he thought should also be associated with the 16th president. This list of a dozen Lincoln Bibles has not been critiqued or updated since that time, 1951. But a few significant discoveries, particularly in the past decade, justify a fresh look at this subject. In this article I update the status of the twelve previously identified historic Lincoln Bibles, discuss which Bibles Lincoln used while presi- dent, and introduce four previously unidentified Bibles that should be added to this list. One of these “new” Bibles may have been used by Lincoln’s mother to teach him how to read when he was a child, and another was probably read by Lincoln when he was president. These sixteen Bibles are shown in the table. The first twelve are presented in the order that Warren and Barton discussed them. In Lincoln Lore, Warren wrote that the Bible was “the single most influential book that Abraham Lincoln read.”3 An extensive study of Lincoln’s use of the Bible is beyond the scope of this article, but suffice it to say that Lincoln utilized the Scriptures extensively to support his ethical and political statements. -

Reviewing the Civil War and Reconstruction Center for Legislative Archives

Reviewing the Civil War and Reconstruction Center for Legislative Archives Address of the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society NAID 306639 From 1830 on, women organized politically to reform American society. The leading moral cause was abolishing slavery. “Sisters and Friends: As immortal souls, created by God to know and love him with all our hearts, and our neighbor as ourselves, we owe immediate obedience to his commands respecting the sinful system of Slavery, beneath which 2,500,000 of our Fellow-Immortals, children of the same country, are crushed, soul and body, in the extremity of degradation and agony.” July 13, 1836 The Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society was founded in 1832 as a female auxiliary to male abolition societies. The society created elaborate networks to print, distribute, and mail petitions against slavery. In conjunction with other female societies in major northern cities, they brought women to the forefront of politics. In 1836, an estimated 33,000 New England women signed petitions against the slave trade in the District of Columbia. The society declared this campaign an enormous success and vowed to leave, “no energy unemployed, no righteous means untried” in their ongoing fight to abolish slavery. www.archives.gov/legislative/resources Reviewing the Civil War and Reconstruction Center for Legislative Archives Judgment in the U.S. Supreme Court Case Dred Scott v. John F. A. Sanford NAID 301674 In 1857 the Supreme Court ruled that Americans of African ancestry had no constitutional rights. “The question is simply this: Can a Negro whose ancestors were imported into this country, and sold as slaves, become a member of the political community formed and brought into existence by the Constitution of the United States, and as such, become entitled to all the rights and privileges and immunities guaranteed to the citizen?.. -

LINCARNATIONS August 2016

Volume 24 No. 1 LINCARNATIONS August 2016 “Would I might rouse the Lincoln in you all” Taking Care of Business Note from Murray Cox, ALP Treasurer: Those of you who at- tended our conference in Vandalia in 2015 recall that after Col- leen Vincent (California) took a fall, a free will offering was tak- en up and sent to her and her husband, Roger, to help with related expenses. At our annual business meeting this year, I failed to mention that a nice note was received from the Vincents, thank- ing us for our thoughtfulness. I belatedly mention this now to those of you who donated to this cause, so you will know that your efforts were acknowledged and appreciated by the Vincents. As always, we urge all of you who have email access to make sure the organization has your correct address. Please send ANY updated contact information to: John Cooper, Membership Chair, fourscore7yearsa- [email protected]; 11781 Julie Dr., Baltimore, Ohio 43105, and to ALP President Stan Wernz, [email protected]; 266 Compton Ridge Dr., Cincinnati, Ohio 45215. We continue to invite you to share your ALP communication ide- as with the Lincarnations team: Vicki Woodard, ([email protected], 217-932-5378); Dean Dorrell (abe@honest- abe.com, 812-254-7315); and Gerald Payn ([email protected], 330-345-5547). ASSOCIATION OF LINCOLN PRESENTERS PRESENTERS OF LINCOLN ASSOCIATION Inside this issue: Letter from Stan Wernz 2 Conference Report 3 Book Review: “Lincoln's Battle with God” 5 Mary’s Velvet Rose 6 In Memoriam 8 Page 2 LINCARNATIONS Association of Lincoln Presenters 266 Compton Ridge Drive Cincinnati, Ohio 45215 Greetings, ALP Members! May 9, 2016 The 22nd annual conference of the Association of Lincoln Presenters was held in Santa Claus, Ind. -

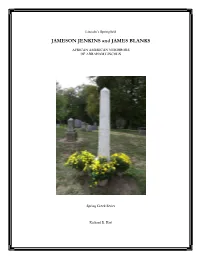

JAMESON JENKINS and JAMES BLANKS

Lincoln’s Springfield JAMESON JENKINS and JAMES BLANKS AFRICAN AMERICAN NEIGHBORS OF ABRAHAM LINCOLN Spring Creek Series Richard E. Hart Jameson Jenkins’ Certificate of Freedom 1 Recorded With the Recorder of Deeds of Sangamon County, Illinois on March 28, 1846 1 Sangamon County Recorder of Deeds, Deed Record Book 4, p. 21, Deed Book AA, pp. 284-285. Jameson Jenkins and James Blanks Front Cover Photograph: Obelisk marker for graves of Jameson Jenkins and James Blanks in the “Colored Section” of Oak Ridge Cemetery, Springfield, Illinois. This photograph was taken on September 30, 2012, by Donna Catlin on the occasion of the rededication of the restored grave marker. Back Cover Photograph: Photograph looking north on Eighth Street toward the Lincoln Home at Eighth and Jackson streets from the right of way in front of the lot where the house of Jameson Jenkins stood. Dedicated to Nellie Holland and Dorothy Spencer The Springfield and Central Illinois African American History Museum is a not-for-profit organization founded in February, 2006, for the purpose of gathering, interpreting and exhibiting the history of Springfield and Central Illinois African Americans life in the 19th, 20th and 21st centuries. We invite you to become a part of this important documentation of a people’s history through a membership or financial contribution. You will help tell the stories that create harmony, respect and understanding. All proceeds from the sale of this pamphlet will benefit The Springfield and Central Illinois African American History Museum. Jameson Jenkins and James Blanks: African American Neighbors of Abraham Lincoln Spring Creek Series. -

Who Was Robert Todd Lincoln?

WHO WAS ROBERT TODD LINCOLN? He was the only child of Abe and Mary Lincoln to survive into adulthood - with his three brothers having died from illness at young ages. Believe it or not, Robert lived until 1926, dying at age 83. But along the way, he sure lived a remarkable life. For starters, he begged his father for a commission to serve in the Civil War, with President Lincoln refusing, saying the loss of two sons (to that point) made risking the loss of a third out of the question. But Robert insisted, saying that if his father didn't help him, he would join on his own and fight with the front line troops; a threat that drove Abe to give in. But you know how clever Abe was. He gave Robert what he wanted, but wired General Grant to assign "Captain Lincoln" to his staff, and to keep him well away from danger. The assignment did, however, result in Robert's being present at Appomattox Court House, during the historic moment of Lee's surrender. Then - the following week, while Robert was at the White House, he was awakened at midnight to be told of his father's shooting, and was present at The Peterson House when his father died. Below are Robert's three brothers; Eddie, Willie, and Tad. Little Eddie died at age 4 in 1850 - probably from thyroid cancer. Willie (in the middle picture) was the most beloved of all the boys. He died in the White House at age 11 in 1862, from what was most likely Typhoid Fever. -

IILY ALBUM Robert Tcxld Loncoln Beckwith ( 1904-1985)

(')f/Hf/11 ~'/ / .'J.f/J teenth Pre'ldent. In 1965 he v.:h introduced to T HE L INCOLN FA\'IILY ALBUM Robert Tcxld Loncoln Beckwith ( 1904-1985). By Mark£. Neely. JJ: & Harold 1/ol:er the grcat-gran<hon of Prc,idcnt Lincoln. Thi' New York: Douhlec/ay.{/990{ meeting rc>ultcd in the eventual di,covery of m:U1) hotherto unknown Lincoln trea>ure,, not the lea.\! of Quarro. clorlr /mu/ing.xil'./72. {3/ (l<tges. S35.00 \\hich are the collectton of albums and photographs prc A Re1·inr by Ralph Geoffrey Neawuw SCI"ed for posterit) by four generation; of the Lincolns. We arc all indebted to the Lincoln National Life fn,ur Writing to llarvey G. E.1Stman. a Poughkeepsie. New :o~k :tncc Company for it' devotion to American hi-tory. particu abolitionist. who had requested a photograph of the llhnoas larly the Abraham Lincoln 'tory, and for acquiring thb lawyer-politician. Abmham Lincoln replied " I h:avc not a superb collection and placmg it m The Loncoln MlL\e~m on ,angle one nov. :u m) control: but I thin~ you can ~a,il) get Fort \\'a)ne. Indiana v.hcre It v.ill be a\atlable forth" and one at New-Yorl.. While I ""' there I "a' taken to one of future generations. In the many }Cal'\ \!nee th founding. the place-' "here they get up 'uch tlnng,, and I >uppo-e they Lincoln Life has given more than mere "hp o;ervice" to 1t' got my shaddow. and can multiply copie' indelinitely." use of the Lincoln name. -

Review Essay

Review Essay THOMAS R. TURNER Thomas J. Craughwell. Stealing Lincoln’s Body. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 2007. Pp. 250. In a story about Thomas J. Craughwell’s Stealing Lincoln’s Body on the CNN.com Web site, Bob Bender, senior editor of Simon and Schuster, notes that Abraham Lincoln has been a best-selling subject, probably since the month after he died. While Lincoln scholars have occasion- ally agonized that there is nothing new to be said about Lincoln— witness James G. Randall’s 1936 American Historical Review article, “Has the Lincoln Theme Been Exhausted?”—books about the sixteenth president continue to pour forth unabated. (This soul searching seems unique to the Lincoln field; one is hard put to think of another research field where scholars raise similar concerns.) If anything, the pace may be accelerating, with the approaching bicentennial of Lincoln’s birth in 2009 calling renewed attention to all facets of his life and career. Bender also cites the old adage that, in the publishing world, books on animals, medicine, and Lincoln are always guaranteed best-sellers. George Stevens in 1939 published a book titled Lincoln’s Doctor’s Dog & Other Famous Best Sellers, and in 2001 Richard Grayson produced a work with a similar title. Neither book sold many copies; Grayson’s sold fewer than two hundred, causing him to write “The only thing I can come up with is that Lincoln isn’t as popular as he used to be.” Given the limitations on press budgets, the number of copies of a book that must be sold to make a profit, a decline in the number of Lincoln collectors, and severe restrictions on library budgets, Grayson may be correct: merely publishing a Lincoln book is no longer a guar- antee of financial success. -

Custodians at Lincoln's Tomb John Carroll Power Edward S

LINCOLN LORE Bulletin of the Lincoln National Life Foundation ------ Dr. Lona A. Warren Editor Published each week by The Lincoln National Life Insurance Company, Fort Wayne, fudiana Number 1078 FORT WAYNE, INDIANA December 5, 1949 CUSTODIANS AT LINCOLN'S TOMB JOHN CARROLL POWER EDWARD S. JOHNSON HERBERT WELLS FAY 1874-1894, 20 years 1895-1920, 25 years 1921-1949, 28 years The first full time custodian of the A native of Springfield Illinois, Bringing to a proper clin1ax this Lincoln Tomb at Springfield, lllinois Edward S. Johnson became the sec most remarkable exhibition of fidelity, was John C. Power. He was born in ond custodian at the Lincoln Tomb. stamina and enterprise in this three Fleming County Kentucky on Sep He was born August 9, 1843 and with man public service succession ex_... tember 19, 1819, but did not come into the exception of the years spent in tending over 73 years, Herbert Wells prominence as an authority in the military sernce and a short time in Fay, labored long<ll' and lived longer Lincoln field until he became associ Chicago, resided in the city all his than either of his two predecessors. ated with the Springfield Board of life. His father and Abraham Lincoln This issue of Lincoln Lore is most Trade. In 1871 he published for that were close friend'!, and Edward John sincerely dedicated to his memory, not organization a History of S'(YI'ingfield. son and Robert Lincoln were school only for his long and faithful service, The last four pages ot the history mates-but eight days separating but for his unusual enthusiasm for were utilized in telling ~ the story of their respective births. -

“The Wisest Radical of All”: Reelection (September-November, 1864)

Chapter Thirty-four “The Wisest Radical of All”: Reelection (September-November, 1864) The political tide began turning on August 29 when the Democratic national convention met in Chicago, where Peace Democrats were unwilling to remain in the background. Lincoln had accurately predicted that the delegates “must nominate a Peace Democrat on a war platform, or a War Democrat on a peace platform; and I personally can’t say that I care much which they do.”1 The convention took the latter course, nominating George McClellan for president and adopting a platform which declared the war “four years of failure” and demanded that “immediate efforts be made for a cessation of hostilities, with a view to an ultimate convention of the states, or other peaceable means, to the end that, at the earliest practicable moment, peace may be restored on the basis of the Federal Union of the States.” This “peace plank,” the handiwork of Clement L. Vallandigham, implicitly rejected Lincoln’s Niagara Manifesto; the Democrats would require only union as a condition for peace, whereas the Republicans insisted on union and emancipation. The platform also called for the restoration of “the rights of the States 1 Noah Brooks, Washington, D.C., in Lincoln’s Time, ed. Herbert Mitgang (1895; Chicago: Quadrangle Books, 1971), 164. 3726 Michael Burlingame – Abraham Lincoln: A Life – Vol. 2, Chapter 34 unimpaired,” which implied the preservation of slavery.2 As McClellan’s running mate, the delegates chose Ohio Congressman George Pendleton, a thoroughgoing opponent of the war who had voted against supplies for the army. As the nation waited day after day to see how McClellan would react, Lincoln wittily opined that Little Mac “must be intrenching.” More seriously, he added that the general “doesn’t know yet whether he will accept or decline. -

The Assassination of Abraham Lincoln • 150 Years After Lincoln's Assassination, Equality Is Still a Struggle

Social Science Department United States History I June 8-12 Greetings USI Students! We hope you are safe and well with your families! Below is the lesson plan for this week: Content Standard: Topic 5. The Civil War and Reconstruction: causes and consequences Civil War: Key Battles and Events Practice Standard(s): 1. Develop focused questions or problem statements and conduct inquiries. 2. Organize information and data from multiple primary and secondary sources. 3. Argue or explain conclusions, using valid reasoning and evidence. Weekly Learning Opportunities: 1. Civil War Timeline and Journal Entry Assignment 2. Historical Civil War Speeches and Extension Activity: • Emancipation Proclamation • The Gettysburg Address 3. Newsela Articles: President Lincoln • Time Machine (1865): The assassination of Abraham Lincoln • 150 years after Lincoln's assassination, equality is still a struggle Additional Resources: • Civil War "The True Story of Glory Continues" - 1991 Documentary sequel https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lXyhTnfAV1o • Glory (1989) - Matthew Broderick, Denzel Washington, Cary Elwes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2LP4tPnCZt4 Note to students: Your Social Science teacher will contact you with specifics regarding the above assignments in addition to strategies and recommendations for completion. Please email your teacher with specific questions and/or contact during office hours. Assignment 1: Civil War Battle Timeline Directions: 1. Using this link https://www.historyplace.com/civilwar/, create a timeline featuring the following events: 1. Election of Abraham Lincoln 2. Jefferson Davis named President 3. Battle of Ft. Sumter 4. Battle of Bull Run 5. Battle of Antietam 6. Battle of Fredericksburg 7. Battle of Chancellorsville 8. Battle of Shiloh 9. -

Homes of Lincoln

Homes of Lincoln Overview: Students will learn about the homes of Lincoln and how these homes shaped Lincoln to become who he was. Materials: ° Lincoln Homes Graphic Organizer ° Lincoln Homes Background Sheets Citation: ° Abraham Lincoln Birthplace: http://www.nps.gov/abli/index.htm ° Lincoln’s Boyhood National Memorial: http://www.nps.gov/LIBO/index.htm ° Lincoln’s Springfield Home: http://www.nps.gov/liho/the-lincoln-home.htm ° Mr. Lincoln’s White House: http://www.mrlincolnswhitehouse.org/inside.asp?ID=3&subjectID=3 ° President Lincoln’s Cottage: http://www.lincolncottage.org/about/lincoln.htm DC Skills (Grades 6-8): Chronology and Historical Interpretation: 1. Students explain how major events are related to one another in time. 4. Students understand and distinguish cause, effect, sequence, and correlation in historical events, including the short-term causes or sparks from long-term causes. Essential Questions: ° How does a person’s environment and experiences shape who them become? ° What can we learn about Abraham Lincoln from his life experiences growing up and growing older? ° How did Lincoln’s life experiences shape him as a president? Background Information: Lincoln lived in four locations in his life. He was born in Kentucky, moved to Indiana as a young boy and spent his teenage years there, and moved to Springfield as a young professional, living there with his family until he was elected president. As a president he resided in the White House and traveled to his summer cottage in the warmer DC months. Each of his homes provided him with different experiences and gave him different skill sets which served him well as president. -

Was John Wilkes Booth's Conspiracy Successful?

CHAPTER FIVE Was John Wilkes Booth’s Conspiracy Successful? Jake Flack and Sarah Jencks Ford’s Theatre Ford’s Theatre is draped in mourning, 1865. Was John Wilkes Booth’s Conspiracy Successful? • 63 MIDDLE SCHOOL INQUIRY WAS JOHN WILKES BOOTH’S CONSPIRACY SUCCESSFUL? C3 Framework Indicator D2.His.1.6-8 Analyze connections among events and developments in broader historical contexts. Staging the Compelling Question Students will analyze primary source documents related to the Lincoln assassination to construct an argument on the success or failure of Booth’s plan. Supporting Question 1 Supporting Question 2 Supporting Question 3 What was the goal of Booth’s What were the the immediate How did Booth’s actions affect conspiracy? results of that plot? Reconstruction and beyond? Formative Formative Formative Performance Task Performance Task Performance Task Create a list of reasons of why Write a one-paragraph news Make a claim about the effect of Booth might have first wanted to report describing what happened Booth’s actions on Reconstruction. kidnap and then decided to kill immediately after Lincoln’s death. Lincoln and other key government leaders. Featured Sources Featured Sources Featured Sources Source A: Excerpts from Booth’s Source A: Overview of the Source A: Overview of diary assassination aftermath Reconstruction Source B: Excerpts from Lincoln’s Source B: Excerpt from a letter Source B: “President Johnson final speech from Willie Clark Pardoning the Rebels”—Harper’s Source C: Events of April, 1865 Source C: Excerpt from a letter Weekly 1865 Source D: Conspirator biographies from Dudley Avery Source C: “Leaders of the and photos Democratic Party”—Political Cartoon by Thomas Nast Source D: Overview of Lincoln’s legacy Summative Performance Task ARGUMENT: Was John Wilkes Booth’s conspiracy successful? Construct an argument (e.g., detailed outline, poster, essay) that discusses the compelling question using specific claims and relevant evidence from historical sources while acknowledging competing views.