Review Essay

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JAMESON JENKINS and JAMES BLANKS

Lincoln’s Springfield JAMESON JENKINS and JAMES BLANKS AFRICAN AMERICAN NEIGHBORS OF ABRAHAM LINCOLN Spring Creek Series Richard E. Hart Jameson Jenkins’ Certificate of Freedom 1 Recorded With the Recorder of Deeds of Sangamon County, Illinois on March 28, 1846 1 Sangamon County Recorder of Deeds, Deed Record Book 4, p. 21, Deed Book AA, pp. 284-285. Jameson Jenkins and James Blanks Front Cover Photograph: Obelisk marker for graves of Jameson Jenkins and James Blanks in the “Colored Section” of Oak Ridge Cemetery, Springfield, Illinois. This photograph was taken on September 30, 2012, by Donna Catlin on the occasion of the rededication of the restored grave marker. Back Cover Photograph: Photograph looking north on Eighth Street toward the Lincoln Home at Eighth and Jackson streets from the right of way in front of the lot where the house of Jameson Jenkins stood. Dedicated to Nellie Holland and Dorothy Spencer The Springfield and Central Illinois African American History Museum is a not-for-profit organization founded in February, 2006, for the purpose of gathering, interpreting and exhibiting the history of Springfield and Central Illinois African Americans life in the 19th, 20th and 21st centuries. We invite you to become a part of this important documentation of a people’s history through a membership or financial contribution. You will help tell the stories that create harmony, respect and understanding. All proceeds from the sale of this pamphlet will benefit The Springfield and Central Illinois African American History Museum. Jameson Jenkins and James Blanks: African American Neighbors of Abraham Lincoln Spring Creek Series. -

Custodians at Lincoln's Tomb John Carroll Power Edward S

LINCOLN LORE Bulletin of the Lincoln National Life Foundation ------ Dr. Lona A. Warren Editor Published each week by The Lincoln National Life Insurance Company, Fort Wayne, fudiana Number 1078 FORT WAYNE, INDIANA December 5, 1949 CUSTODIANS AT LINCOLN'S TOMB JOHN CARROLL POWER EDWARD S. JOHNSON HERBERT WELLS FAY 1874-1894, 20 years 1895-1920, 25 years 1921-1949, 28 years The first full time custodian of the A native of Springfield Illinois, Bringing to a proper clin1ax this Lincoln Tomb at Springfield, lllinois Edward S. Johnson became the sec most remarkable exhibition of fidelity, was John C. Power. He was born in ond custodian at the Lincoln Tomb. stamina and enterprise in this three Fleming County Kentucky on Sep He was born August 9, 1843 and with man public service succession ex_... tember 19, 1819, but did not come into the exception of the years spent in tending over 73 years, Herbert Wells prominence as an authority in the military sernce and a short time in Fay, labored long<ll' and lived longer Lincoln field until he became associ Chicago, resided in the city all his than either of his two predecessors. ated with the Springfield Board of life. His father and Abraham Lincoln This issue of Lincoln Lore is most Trade. In 1871 he published for that were close friend'!, and Edward John sincerely dedicated to his memory, not organization a History of S'(YI'ingfield. son and Robert Lincoln were school only for his long and faithful service, The last four pages ot the history mates-but eight days separating but for his unusual enthusiasm for were utilized in telling ~ the story of their respective births. -

Papers of the 2009 Dakota Conference

Papers of the Forty-first Annual DAKOTA CONFERENCE A National Conference on the Northern Plains “Abraham Lincoln Looks West” Augustana College Sioux Falls, South Dakota April 24-25, 2009 Complied by Lori Bunjer and Harry F. Thompson Major funding for the Forty-first Annual Dakota Conference was provided by Loren and Mavis Amundson CWS Endowment/SFACF, Deadwood Historic Preservation Commission, Carol Martin Mashek, Elaine Nelson McIntosh, Mellon Fund Committee of Augustana College, Rex Myers and Susan Richards, Blair and Linda Tremere, Richard and Michelle Van Demark, Jamie and Penny Volin, and the Center for Western Studies. The Center for Western Studies Augustana College 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface Abbott, Emma John Dillinger and the Sioux Falls Bank Robbery of 1934 Amundson, Loren H. Colton: The Town Anderson, Grant K. The Yankees are Coming! The Yankees are Coming! Aspaas, Barbara My Illinois Grandmother Speaks Bradley, Ed Civil War Patronage in the West: Abraham Lincoln’s Appointment of William Jayne as Governor of the Dakota Territory Braun, Sebastian F. Developing the Great Plains: A Look Back at Lincoln Browne, Miles A. Abraham Lincoln: Western Bred President Ellingson, William J. Lincoln’s Influence on the Settlement of Bend in the River (Wakpaipaksan) Hayes, Robert E. Lincoln Could Have Been in the Black Hills — Can You Believe This? Johnson, Stephanie R. The Cowboy and the West: A Personal Exploration of the Cowboy’s Role in American Society Johnsson, Gil In the Camera’s Eye: Lincoln’s Appearance and His Presidency Johnsson, -

Lincoln, Slavery and Springfield: How Public Opinion in Central Illinois Influenced Abraham Lincoln's Positions on Slavery

Lincoln, Slavery and Springfield: How Public Opinion in Central Illinois Influenced Abraham Lincoln's Positions on Slavery The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Mcclelland, Edward. 2019. Lincoln, Slavery and Springfield: How Public Opinion in Central Illinois Influenced Abraham Lincoln's Positions on Slavery. Master's thesis, Harvard Extension School. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:42004076 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Lincoln, Slavery and Springfield: How Popular Opinion in Central Illinois Influenced Abraham Lincoln’s Views on Slavery Edward McClelland A Thesis in the Field of History for the Degree of Master of Liberal Arts in Extension Studies Harvard University March 2019 !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Copyright 2018 [Edward McClelland] "!! ! Abstract Abraham Lincoln won the Republican nomination in 1860 because he was seen as less radical on the slavery than his rivals William Seward and Salmon P. Chase, and less conservative than Edward Bates. This thesis explores how his career as a politician in Central Illinois – a region that contained of mix of settlers from both New England and the South – required him to navigate between the extremes of the slavery question, -

The Transformation of the Lincoln Tomb

The Lincoln Landscape The Transformation of the Lincoln Tomb NANCY HILL Abraham Lincoln’s burial place was designed and constructed in an age of sideshows and curiosities. The display of relic collections and memorabilia was an expected part of museums and other public at- tractions in the late nineteenth century. It was the beginning of the age of tourism, when visitors enjoyed many kinds of local oddities as part of their travel experience. The professionalization of museum and park management was still decades away. Caretakers, rather than curators, were employed to oversee sites such as Lincoln’s New Sa- lem, the Lincoln Home, and the Lincoln Tomb. Although most of the caretakers performed their duties with care and dedication, public expectations began to change, and different management strategies eventually were adopted. The original design of the Lincoln Tomb was deficient for the secu- rity of the president’s remains. It was also structurally unsound and inappropriate to the commemoration of his life. Lincoln’s increasingly elevated status in history necessitated changes to the structure and a radical departure from its original design and use. A decades-long struggle transformed the tomb from an ordinary tourist attraction to a dignified monument honoring the memory of Abraham Lincoln and the symbol that he had become. The First Monument to Lincoln Springfield, Illinois, grew rapidly in the 1850s. The Old City Grave- yard was closed by mid-decade, and the Hutchinson Cemetery, where Eddie Lincoln was buried in 1850, was rapidly reaching its capacity. In 1855 the city council acquired seventeen wooded acres for a new cemetery north of the city limits. -

James Adams of Springfield, Illinois 33

Black: James Adams of Springfield, Illinois 33 James Adams of Springfield, Illinois: The Link between Abraham Lincoln and Joseph Smith Susan Easton Black Historians Richard L. Bushman and Bryon C. Andreasen have searched for evidence to connect the life of Joseph Smith with Abraham Lincoln.1 Cir- cumstances place Smith actually in Springfield, Illinois, on two occasions— in early November 1839 (while en route east to Washington DC), and again during the last week of December 1842 and the first week of January 1843 (during his hearing before federal judge Nathaniel Pope). At the same time, Lincoln was an elected representative from Sangamon County to the state legislature (he voted in favor of the Nauvoo Charter), and a Springfield law- yer in the Eighth Circuit District Court of Illinois. Yet, historical evidence is not conclusive whether either man tipped a hat to the other. It has been well- argued that Lincoln and Smith lived separate lives.2 However, such an argument fails to recognize the role of Democrat James Adams in the lives of Lincoln and Smith. Both men not only knew Adams, they spoke of him in public places and wrote of him in newsprint and private correspondence. Honest Abe characterized Adams as “a forger, a whiner, a fool, and a liar.”3 Smith touted Adams as a pillar of society. Without the jux- taposition of these two men, the life of Adams may not be worth much men- tion except as a side note. But with Lincoln and Smith expressing divergent opinions, the life of James Adams takes on greater significance. -

Power's Books on Oak Ridge Monument

L~N COLN LORE Bulletin of the Lincoln National Life Foundation • • • • - Dr. Louis A. Warren, Editor Publlshed each week by The Lincoln National Lite Insurance Company, Fort Wayne, Indiana Number 934 FORT WAYNE, INDIANA March 3, 1947 POWER'S BOOKS ON OAK RIDGE MONUMENT The Board of Managers of Oak Ridge Cemetery at picture of monument and baekstrip inscribed, "'Life/of/ Springfield, Illinois, has just issued a very attractive Lincoln I Power I (device) I Monumental/Edition/ (Publish map. It visualizes tne recent effort of the Board to give er's symbol)." Frontispiece engraving of Meserve #77. the surroundings of Lincoln's monument a more historic Title page same as above. Three copyright notices on atmosphere by designating the drives with names back of title page, nlustrated, pages 352, 7% x 514. familiar in Lincoln's day and using terminology appro· priate to this resting .Place for the dead. The map is in 6. Deluxe Edition color_, embelllshed w1th four pictures and measures Same as above except bound in %. morocco. 21% x 16'A. It may be secured by enclosing the cost of printing and mailing (35 cents) in correspondence ad THE EXTENDED VOLUMES dressed: Superintendent, Oak Ridge Cemetery, Spring 7. Third Edition field, Dlinois. Bound in brown cloth with gilt lettering but cover This new map so recently published recalls earlier desig:t> changed and backstrip inscribed, "Li!e/of/Lin attempts to supply diagrams of the burial grounds also eoln/Power/Monument.al/Edition." Frontispiece changed descriptive information about Oak Ridge Cemetery and to engraving of Meserve !r,S7. -

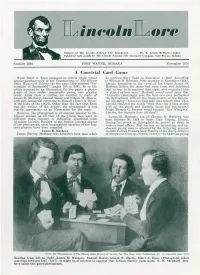

A Convivial Card Game

Oulltotin u( Th.~ Un('oln NaHon11l J.. ilf' f·ounda tion • . • 1).-. ll. G~n• ld .\t('"t urtry, f..dltor Publhh«< f"Ath month b.r Tbe! Lin~oln Nat ional l...i(f" l n-ul'anef' ComJ•nny, Fori WaJ·ne, Indiana Number 1593 FORT WAYNE, INDIANA November 1970 A Convivial Card Gam e When Zimri A. Enos prepared an article which would he married Mary Todd on November 4, 1842. According appear posthumously in the Transactions of The 1Uinoi8 to William H. Herndon, "One morning in No\•ember (4th), State Historiccrl Society for the year 1909 entitled "De Lincoln hastening to the J'OOm of his friend J~\mes H. scription of Springfield" (pages 190 to 208), he or the Matheny before the latter had risen from bed, informed editor inserted as an illustration for the paper a photo~ that he was to be married that night, and requested him graph of four rather remarkable young men playing t.Q attend as best man." Matheny \vould recall later that cards. Aside from a cutline, no ment,ion is made of "Lincoln's (marl'iage) was the first one ever performed James H. Matheny, Samuel Baker and Gibson W. Harris, (in Springfield) with all the requirements of the Episco with only occasional reference to himself (Zimri A. Enos) pal ceremony." Lincoln's ~st man also related that when in the body of the artiele. Other than the faet that Enos Lincoln repeated the words "with this ring I thee endow was the author of the article, the photograph is not with all my goods and chattels, lands and t-enements," exactly appropriate as an illustration for the topic. -

Stealing Lincoln

SPRING STUDENT ENRICHMENT PACKET RESEARCH SIMULATION TASK & READING LOG Grade 8 STEALING LINCOLN Reading/English Language Arts Note to Students: You've learned so much in school so far! It is important that you keep your brain active over the break. In this package you will find a calendar of activities to last you all Spring Break. This year we have also incorporated a fun project for you to complete. Once you have completed the activity, create a journal that you can use to note your thoughts, ideas, and any work you complete. Directions: Family members should preview the packet together. There are activities that may require advance planning, or you may want to consider working together with other family and friends on some activities. Students should read for at least 30 minutes each day. Students will need a Reader’s & Writer’s Journal to complete this spring work. Your journal will be your special place for your daily calendar work and writing. Students can purchase a journal or they can make one by stapling several pieces of paper together or by using a notebook/binder with paper. Students should be creative and decorate the journal. Specific journal tasks are given some days, but students may also journal after each day's reading, notice things that stood out, questions that they have, or general wondering about the text. Each journal entry should: have the date and assignment title; have a clear and complete answer that explains the students thinking and fully supports the response; and be neat and organized. Use the chart in this package to record all of the books read during Spring Break. -

Strawbridge--Shepherd House NAME

NPS Form 10-900 0MB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This fo rm is fo r use in nominating or reques ting determinations for individual properties and distri cts . See instructi ~ ati.onal Register _ _ _ Bulletin, How to Co mplete the Na tional Register of Historic Places Registration Fom i. If any item does not app y to tpi;~- _ • doc umented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For fun cti ons, architectural classifi cati on, materials, and areas of · igni ftcfilial,l:ii\ categories and subcategories from the instructi ons. ,-----.-"'4~ - -..-i 1. Name of Property Historic name: Strawbridge-Shepherd House Other names/site number: rJAT.REGISlEROfHSTmncPJ.ACES ------------------- _ N"'10N~I PARKSERV/Gf Name of related multiple property listing: NIA --- (Enter "NI A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing 2. Location Street & number: 5255 Shepherd Road City or town: Springfield State: IL County: -=S=an=g:;,..ca=m=o=nc=-_-=C--=co-=d-"-e:'-=-16"-'7~ Not For Publication: □ Vicinity: □ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this x_ nomination _ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property _X_ meets _ does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant at the following level(s) of significance: national _statewide .J(Iocal Applicable National Register Criteria: _A _B J{_c _D Signature of certifying official/Title: Date tU i k' o 1- s +i{l=b>n:V lt\~h ~h1,~ State or Federal agency/bureau or Tribal Government In my opinion, the property _meets_ does not meet the National Register criteria. -

Chapter Three “Separated from His Father, He Studied English Grammar”: New Salem (1831-1834) in 1848, the Thirty-Nine-Year-O

Chapter Three “Separated from His Father, He Studied English Grammar”: New Salem (1831-1834) In 1848, the thirty-nine-year-old Lincoln offered some sage advice to his law partner, William H. Herndon, who had complained that he and other young Whigs were being discriminated against by older Whigs. In denying the allegation, Lincoln urged him to avoid thinking of himself as a victim: “The way for a young man to rise, is to improve himself every way he can, never suspecting that any body wishes to hinder him. Allow me to assure you, that suspicion and jealousy never did help any man in any situation. There may sometimes be ungenerous attempts to keep a young man down; and they will succeed too, if he allows his mind to be diverted from its true channel to brood over the attempted injury. Cast about, and see if this feeling has not injured every person you have ever known to fall into it.”i By his own account, Lincoln began his emancipated life “a strange, friendless, uneducated, penniless boy.”ii After escaping from his paternal home, he spent three years preparing himself for a way of life far different from the hardscrabble existence that he had been born into. As he groped his way toward a new identity, he improved himself every way he could. i Lincoln to Herndon, Washington, 10 July 1848, in Roy P. Basler et al., eds., Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln (8 vols. plus index; New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1953-55),1:497. 181 Michael Burlingame – Abraham Lincoln: A Life – Vol. -

Lincoln's Springfield: the Underground Railroad

LINCOLN’S SPRINGFIELD: THE UNDERGROUND RAILROAD Spring Creek Series Richard E. Hart Springfield, Illinois 1 Lincoln’s Springfield The Underground Railroad Front Cover Photograph: Springfield African-American Railroad Con- ductor, William H. K. Donnegan The photographer is unknown. Back Cover Photograph: . Through its programs and publications, the Sangamon County Historical Society strives to collect and pre- serve the rich heritage of the Sangamon Valley. As both a destination and a crossroads of American ex- pansion, its stories give insight into the growth of the nation. All proceeds from the sale of this pamphlet will benefit the Sangamon County Historical Society. Sangamon County Historical Society 308 E. Adams Springfield, Illinois 62701 217-522-2500 Sancohis.org Lincoln’s Springfield: The Underground Railroad Spring Creek Series. Copyright 2006 by Richard E. Hart, Springfield, Illinois. All rights reserved. First Printing, September, 2006. 2 37 Watermills of the Sangamo Country, Curtis Mann, Under the Prairie Founda- tion, Popular Series # 1, 2004, pp. 18-19. Lincoln’s Springfield 1866 and 1869 Springfield City Directory. The Underground Railroad The Public Patron, Springfield, Illinois, May 1898, p. 3. The Sociogenesis of a Race Riot, Springfield, Illinois in 1908, Roberta Senechal, University of Illinois Press, Urbana and Chicago, 1990, pp. 43-46, 96, 99, 131, 136, 138-39, 169-71, and 174. The Springfield Race Riot of 1908, Deepak Madala, Jennifer Jordan, and August Appleton, http://library.thinkquest.org/2986/Killed.html. Other interesting web sites FORWARD concerning Donnegan and the 1908 Springfield Race Riot are: Ruth Ellis's Tale of Two Cities: A Modern Fairy Tale in Black & White, http://www.keithboykin.com/author/ruth1.html.