Papers of the 2009 Dakota Conference

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pbr Tours & World Finals

PBR TOURS & WORLD FINALS PBR TOURS & WORLD FINALS PBR USA Tours ............................... 2 PBR Unleash The Beast ........................ 2 PBR Pendleton Whisky Velocity Tour ............. 3 PBR Touring Pro Division ....................... 4 PBR Australia ................................. 5 PBR Brazil ................................... 6 PBR Canada .................................. 7 PBR Mexico .................................. 8 PBR World Finals ............................. 9 2020 PBR World Champion .................... 10 2020 PBR World Finals Event Winner and Rookie of the Year ........................ 12 2020 YETI PBR World Champion Bull ........... 13 2020 PBR World Finals Awards ................ 15 2020 PBR World Finals Event Results ........... 16 PBR TOURS & WORLD FINALS PBR USA TOURS The PBR brings “America’s Original Extreme Sport” to major arenas across the United States with the nationally-televised Unleash The Beast, featuring the Top 35 bull riders in the world, in addition to the Pendleton Whisky Velocity Tour and Touring Pro Division, the PBR’s expansion and developmental tours. respectively. Each event pits the toughest bull riders in the world against the top bovine athletes on the planet. During two hours of heart-pounding, bone-crushing, edge-of-your-seat excitement fans are entertained by the thrills and spills on the dirt against the back drop of the show’s rocking music and pyrotechnics. It is world class athleticism and entertainment rolled into one, unlike any other major-league sport. UNLEASH THE BEAST The PBR’s nationally- televised Unleash The Beast (UTB) features the world’s Top 35 bull riders going head-to-head against the fiercest bucking bulls on the planet. During a regular-season, two-day UTB event, each of the 30 riders will ride in one round each day - Round 1 and Round 2. -

NEWSLETTER Holiday Open House & Bake Sale

2013 Fall PRESERVING HISTORY Volume 35 No. 2 NEWSLETTER Holiday Open House Crow Wing County Museum & Bake Sale & Research Library Restored Sheriff’s Residence At the Museum Open to the public Friday, December 13th MISSION STATEMENT 3 –7 pm The Crow Wing County Enjoy hot apple cider/coffee Historical Society is committed to Punch & cookies preserving the history New exhibits and telling the story of Crow Wing County. STAFF Brainerd book available in the museum gift shop Pam Nelson Director/Administrator Newsletter Editor Lynda Hall Assistant Administrator Darla Sathre Administrative Assistant Experience Works Staff Lyn Lybeck Bonnie Novick 2013 FALL NEWSLETTER President’s Report It's hard to believe we are well into November with Christmas just around the corner. We have had a busy yet eventful year. Our annual meeting was a success, although there is always room for more attendees. Our museum continues to receive rave reviews from our visitors that tour our building. The remodeling has added room for more displays, thank you and Bake Sale to the staff and volunteers who worked very hard to make these improvements a reality. A special thanks to board member Ron Crocker and his son Jeff for making it all possible. OPEN TO THE PUBLIC The open house in October highlighted the unveiling of a large portrait of Lyman White. We Friday, Dec. 13 3-7 pm were fortunate to have Mayor James Wallin do the honors before a very nice crowd. Lyman White is the gentleman who is recognized as the person who actually laid out the Cider, Coffee, Punch boundaries of the city of Brainerd. -

Bremer Kidnapping Part 131.Pdf

r _ I ... .. I, g .e_¢.5.,_> " _ - ~¢;.;, __ -V? ,_ g . B.»- . 92 I t O O the kidnaping before it started but that Sawyer insisted upon going through with it. Bolton testified that some of the boys often expressed themselves as being opposed to Harry $awyer's policy of "fooling with the Government", and that they were very much worried about this matter and they oftn made the eonment that had it not been for Harry Sawyer they would not have gone through with the kidnaping. PATRICIA CHERRINGRJN who was the consort of John Hamilton during 1953 and 1934 and who is presently serving a two year sentence in the Federal Detention Home at Milan,Michigan for harboring John Dillinger advised agents of the Bureau that shortly after John Dillinger and Homer Van Lister shot their way out of a police trap at their apartment on Lexington Avenue in St.Paul on March 31, 1934, she together with her sister and -Tohn Hamilton proceeded to a restaurant in St.Paul where they contacted Homer Van Meter, who imediately took them to Harry 5awyer's cottage near 5t.Paul where they remained for four days. She further sta- ted that they received a tip that this farm was to be raided ad left l o~ hurriedly, returning to $t.Paul where they then contacted Tonnq Carroll 92 and Baby Face Nelson. ' "1' ii! t 3 VIVIAN !,'L»'iThIIAS, who was the pa:-amour of Vernon C.I-Ziller a _z. principal in the Kansas City massacre advised agents of the Bureau that 1'4 Q she and Killer had lmovm Harry Sawyer for approximtely five years during which period he operated a saloon on Wabaaha Avenue in St.Paul; I Q ,_. -

**** This Is an EXTERNAL Email. Exercise Caution. DO NOT Open Attachments Or Click Links from Unknown Senders Or Unexpected Email

Scott.A.Milkey From: Hudson, MK <[email protected]> Sent: Monday, June 20, 2016 3:23 PM To: Powell, David N;Landis, Larry (llandis@ );candacebacker@ ;Miller, Daniel R;Cozad, Sara;McCaffrey, Steve;Moore, Kevin B;[email protected];Mason, Derrick;Creason, Steve;Light, Matt ([email protected]);Steuerwald, Greg;Trent Glass;Brady, Linda;Murtaugh, David;Seigel, Jane;Lanham, Julie (COA);Lemmon, Bruce;Spitzer, Mark;Cunningham, Chris;McCoy, Cindy;[email protected];Weber, Jennifer;Bauer, Jenny;Goodman, Michelle;Bergacs, Jamie;Hensley, Angie;Long, Chad;Haver, Diane;Thompson, Lisa;Williams, Dave;Chad Lewis;[email protected];Andrew Cullen;David, Steven;Knox, Sandy;Luce, Steve;Karns, Allison;Hill, John (GOV);Mimi Carter;Smith, Connie S;Hensley, Angie;Mains, Diane;Dolan, Kathryn Subject: Indiana EBDM - June 22, 2016 Meeting Agenda Attachments: June 22, 2016 Agenda.docx; Indiana Collaborates to Improve Its Justice System.docx **** This is an EXTERNAL email. Exercise caution. DO NOT open attachments or click links from unknown senders or unexpected email. **** Dear Indiana EBDM team members – A reminder that the Indiana EBDM Policy Team is scheduled to meet this Wednesday, June 22 from 9:00 am – 4:00 pm at IJC. At your earliest convenience, please let me know if you plan to attend the meeting. Attached is the meeting agenda. Please note that we have a full agenda as this is the team’s final Phase V meeting. We have much to discuss as we prepare the state’s application for Phase VI. We will serve box lunches at about noon so we can make the most of our time together. -

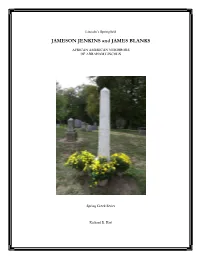

JAMESON JENKINS and JAMES BLANKS

Lincoln’s Springfield JAMESON JENKINS and JAMES BLANKS AFRICAN AMERICAN NEIGHBORS OF ABRAHAM LINCOLN Spring Creek Series Richard E. Hart Jameson Jenkins’ Certificate of Freedom 1 Recorded With the Recorder of Deeds of Sangamon County, Illinois on March 28, 1846 1 Sangamon County Recorder of Deeds, Deed Record Book 4, p. 21, Deed Book AA, pp. 284-285. Jameson Jenkins and James Blanks Front Cover Photograph: Obelisk marker for graves of Jameson Jenkins and James Blanks in the “Colored Section” of Oak Ridge Cemetery, Springfield, Illinois. This photograph was taken on September 30, 2012, by Donna Catlin on the occasion of the rededication of the restored grave marker. Back Cover Photograph: Photograph looking north on Eighth Street toward the Lincoln Home at Eighth and Jackson streets from the right of way in front of the lot where the house of Jameson Jenkins stood. Dedicated to Nellie Holland and Dorothy Spencer The Springfield and Central Illinois African American History Museum is a not-for-profit organization founded in February, 2006, for the purpose of gathering, interpreting and exhibiting the history of Springfield and Central Illinois African Americans life in the 19th, 20th and 21st centuries. We invite you to become a part of this important documentation of a people’s history through a membership or financial contribution. You will help tell the stories that create harmony, respect and understanding. All proceeds from the sale of this pamphlet will benefit The Springfield and Central Illinois African American History Museum. Jameson Jenkins and James Blanks: African American Neighbors of Abraham Lincoln Spring Creek Series. -

Review Essay

Review Essay THOMAS R. TURNER Thomas J. Craughwell. Stealing Lincoln’s Body. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 2007. Pp. 250. In a story about Thomas J. Craughwell’s Stealing Lincoln’s Body on the CNN.com Web site, Bob Bender, senior editor of Simon and Schuster, notes that Abraham Lincoln has been a best-selling subject, probably since the month after he died. While Lincoln scholars have occasion- ally agonized that there is nothing new to be said about Lincoln— witness James G. Randall’s 1936 American Historical Review article, “Has the Lincoln Theme Been Exhausted?”—books about the sixteenth president continue to pour forth unabated. (This soul searching seems unique to the Lincoln field; one is hard put to think of another research field where scholars raise similar concerns.) If anything, the pace may be accelerating, with the approaching bicentennial of Lincoln’s birth in 2009 calling renewed attention to all facets of his life and career. Bender also cites the old adage that, in the publishing world, books on animals, medicine, and Lincoln are always guaranteed best-sellers. George Stevens in 1939 published a book titled Lincoln’s Doctor’s Dog & Other Famous Best Sellers, and in 2001 Richard Grayson produced a work with a similar title. Neither book sold many copies; Grayson’s sold fewer than two hundred, causing him to write “The only thing I can come up with is that Lincoln isn’t as popular as he used to be.” Given the limitations on press budgets, the number of copies of a book that must be sold to make a profit, a decline in the number of Lincoln collectors, and severe restrictions on library budgets, Grayson may be correct: merely publishing a Lincoln book is no longer a guar- antee of financial success. -

Custodians at Lincoln's Tomb John Carroll Power Edward S

LINCOLN LORE Bulletin of the Lincoln National Life Foundation ------ Dr. Lona A. Warren Editor Published each week by The Lincoln National Life Insurance Company, Fort Wayne, fudiana Number 1078 FORT WAYNE, INDIANA December 5, 1949 CUSTODIANS AT LINCOLN'S TOMB JOHN CARROLL POWER EDWARD S. JOHNSON HERBERT WELLS FAY 1874-1894, 20 years 1895-1920, 25 years 1921-1949, 28 years The first full time custodian of the A native of Springfield Illinois, Bringing to a proper clin1ax this Lincoln Tomb at Springfield, lllinois Edward S. Johnson became the sec most remarkable exhibition of fidelity, was John C. Power. He was born in ond custodian at the Lincoln Tomb. stamina and enterprise in this three Fleming County Kentucky on Sep He was born August 9, 1843 and with man public service succession ex_... tember 19, 1819, but did not come into the exception of the years spent in tending over 73 years, Herbert Wells prominence as an authority in the military sernce and a short time in Fay, labored long<ll' and lived longer Lincoln field until he became associ Chicago, resided in the city all his than either of his two predecessors. ated with the Springfield Board of life. His father and Abraham Lincoln This issue of Lincoln Lore is most Trade. In 1871 he published for that were close friend'!, and Edward John sincerely dedicated to his memory, not organization a History of S'(YI'ingfield. son and Robert Lincoln were school only for his long and faithful service, The last four pages ot the history mates-but eight days separating but for his unusual enthusiasm for were utilized in telling ~ the story of their respective births. -

PUNKS! TOPICALITY and the 1950S GANGSTER BIO-PIC CYCLE

cHAPTER 6 PUnKs! TOPIcALItY AnD tHe 1950s gANGSTER BIo-PIc cYcLe ------------------------------- PeteR stAnfield “This is a re-creation of an era. An era of jazz Jalopies Prohibition And Trigger-Happy Punks.” — Baby Face Nelson this essay examines a distinctive and coherent cycle of films, pro- duced in the late 1950s and early 1960s, which exploited the notoriety of Prohibition-era gangsters such as Baby Face Nelson, Al Capone, Bonnie Parker, Ma Barker, Mad Dog Coll, Pretty Boy Floyd, Machine Gun Kelly, John Dillinger, and Legs Diamond. Despite the historical specificity of the gangsters portrayed in these “bio-pics,” the films each display a marked interest in relating their exploits to contemporary topical con- cerns. Not the least of these was a desire to exploit headline-grabbing, sensational stories of delinquent youth in the 1950s and to link these to equally sensational stories of punk hoodlums from 1920s and 1930s. In the following pages, some of the crossovers and overlaps between cycles of juvenile delinquency films and gangster bio-pics will be critically eval- uated. At the centre of analysis is the manner in which many of the films in the 1950s bio-pic gangster cycle present only a passing interest in pe- riod verisimilitude; producing a display of complex alignments between the historical and the contemporary. 185 peter stanfield DeLInQUENTS, gANGSTERs, AnD PUnKs In the 1950s, the representation of gangsters and of juvenile delinquents shared a common concern with explaining deviancy in terms of a rudi- mentary psychology, -

Barker/Karpis Gang Bremer Kidnapping File

FOIPA COVER SHEET FREEDOM OF INFORMATION AND PRIVACY ACTS SUBJECT: BARKER/KARPIS GANG BREMER KIDNAPPING FILE NUMBER: 7-576 SECTION : 147 FEDERAL BUREAU OF INVESTIGATION THE BEST COPY OBTAINABLE IS INCLUDED IN THE REPRODUCTION OF THESE DOCUMENTS. PAGES INCLUDED THAT ARE BLURRED, LIGHT, OR OTHERWISE DIFFICULT TO READ ARE THE RESULT OF THE CONDITION OF THE ORIGINAL DOCUMENT. NO BETTER COPY CAN BE REPRODUCED. sub1a@ I-311.6 DUmB¬R - 5¬CZ5iOT2 nUTDE>¬R___LH.IL__%_____.__ 5¬RiAL5 Z50 Z§792L DA§¬5____L2_________ PA§¬5R¬LeAse >__1l3___________- p;>,_§¬5 w1Z<5DDeLo ;____1_______ ¬X¬mp@i0D! u5¬O > Q ' /7 92 - . ,>< iuumzo STATESBUREAU INVESTIGATIQN OF .9" <Y. ' I 3/.' .. C! lr 92> .' Donn No.4" " E"-encore: mu'-{Q Tms ens: oR|<:|NA'rtb A1 cmcnmm, omo. n. 1. "~-1~<>@""1-""""s.e-:-_ 20 _ _ _ _ I ' * __ 3 ' IQOIT MADII AT - llDATI Hi lAAD£ l f1s,19,2oIDPOI WHICH MAUI RZOIT Ki-Y 5; Q'f_-,:_{£; - Q -~ j. " . KEY YORKCIT! .,.,.. .,12-5-55,_._ ___22 a_=_12/Q35, _ J.B. DICKIBQIH .:-'-'~-/ e Y _ _ = ; » I e 1 r ~ ,~. 1:. WV"-="'r"> TIl'I-ItQ 92' . 2 . t ' O ~ ~ ',3.? I '11"11, .. ouuanorcnm -1?! 'i'~-;--P. mmmo. .-- 1- _ ~ , ~. ._ ALVIN- II OI KLHPI3, "' Iith 511189! .1i4:4i'-;. < Y R, r 1 ; _ oasnmcnon or msmcn, +1 . ,?- ~_' HWLHDGEORGE BRBJIB- _'1¢ii.IQ»;92,.',~','*:92 .2- . -

Fake Trillions, Real Billions, Beetcoin and the Great American Do-Over a Nurture Capitalist’S Notebook

AHA! —————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————- Fake Trillions, Real Billions, Beetcoin and the Great American Do-Over A Nurture Capitalist’s Notebook Woody Tasch © Woody Tasch July, 2020 2 To Washing Bear and Wendell Berry This is the 1st installment of a 7-part series brought to you by Beetcoin.org and the Slow Money Institute. 3 Fixed like a plant on his peculiar spot, To draw nutrition, propagate, and rot; Or meteor-like, flame lawless thro’ the void, Destroying others, by himself destroy’d. —Alexander Pope What happiness! Look how earth, rain, and the odors of dung and the lemon trees all combine and become one with man’s heart! Truly, man is soil. That is why he, like the soil, enjoys the calm caressing rains of spring so very much. My heart is being watered. It cracks open, sends forth a shoot. —Nikos Kazantzakis The day flew by as we looked at the various sheep breeds, many of which I had never seen: short sheep, tall sheep, thin sheep, fat sheep, sheep with black faces, sheep with white faces, and sheep with red faces. Zwartbles, Rouge de l’Ouest, Clun Forest, and a blue- tinted breed called Bleu du Maine. —Linda Faillace Have we forgotten that the most productive investing is the simplest investing, the most peaceable investing? —John Bogle 4 CONTENTS Prologue I AHA! II MYTH III MONEY IV FOOD V THOUGHT Epilogue 5 Deadly Serious is Dead! Long live Lively Serious! 6 PROLOGUE In 1970, Alvin Toffler wrote the bestseller Future Shock, heralding an era of unprecedented innovation and acceleration. We couldn’t quite know how right he was, although the resonance of his message was ineluc- table. -

TOPICALITY and the 1950S GANGSTER BIO-PIC CYCLE

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kent Academic Repository CHAPTER 6 PUNKS! TOPICALITY AND THE 1950s gANgSTER BIO-PIC CYCLE ------------------------------- peter Stanfield “This is a re-creation of an era. An era of jazz Jalopies Prohibition And Trigger-Happy Punks” — Baby Face Nelson this essay examines a distinctive and coherent cycle of films, pro- duced in the late 1950s and early 1960s, which exploited the notoriety of Prohibition-era gangsters such as Baby Face Nelson, Al Capone, Bonnie Parker, Ma Barker, Mad Dog Coll, Pretty Boy Floyd, Machine Gun Kelly, John Dillinger, and Legs Diamond. Despite the historical specificity of the gangsters portrayed in these “bio-pics,” the films each display a marked interest in relating their exploits to contemporary topical con- cerns. Not the least of these was a desire to exploit headline-grabbing, sensational stories of delinquent youth in the 1950s and to link these to equally sensational stories of punk hoodlums from 1920s and 1930s. In the following pages, some of the crossovers and overlaps between cycles of juvenile delinquency films and gangster bio-pics will be critically eval- uated. At the centre of analysis is the manner in which many of the films in the 1950s bio-pic gangster cycle present only a passing interest in pe- riod verisimilitude; producing a display of complex alignments between the historical and the contemporary. 15 peter stanfield DELINQUENTS, gANgSTERS AND PUNKS In the 1950s, the representation of gangsters and of juvenile delinquents shared a common concern with explaining deviancy in terms of a rudi- mentary psychology, which held that criminality was fostered by psycho- pathic personalities. -

Read Papers Presented at the Conference

The Kaisers Totebag: Fundraising, German-Americans and World War I Richard Muller, M.S.S The Kaiser’s Tote bag: Fundraising, German-Americans and WW I Germans are nothing if not about tradition, loyalty, symbolism and generosity. These traits, while not unique to Germans, German-Americans or any ethnicity for that matter, are examined here in the context of generating financial and moral support for various factions engaged in fighting WW I. Two families, one from South Dakota, one from New York City provide the context for this paper. England and France were using loans and war bonds to pay for their role in the Napoleonic War and WW I. The United States eventually followed suit, when it entered the war. Fundraising to support war is nothing new. Fundraisers have used “Thank you Gifts” to help raise money for decades. In the fundraising business there is an old adage, if it works once, beat it to death. 148 In this case, Frederick III took a page out of his great grandfather’s fundraising playbook noting how Frederick I funded the Napoleonic War of 1813. Then, the Prussian Royal family asked loyal German citizens for their gold (rings, jewelry, dinnerware, etc.) to support the Kaiser’s need for the materials of war. In exchange for their donation, they received an iron ring, following the practice of “a ‘Thank You Gift’ in return for a quality, soon to be appreciated premium.” This was a sort of “Thank you” gift at the time, much like today’s fundraisers offer tote bags and coffee mugs for donations.