The Transformation of the Lincoln Tomb

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Illinois' African American History & Heritage

African American History Chicago Bronzeville illinois’ african american history & heritage Take in the rich legacy of Illinois’ African American history In Chicago and throughout the state, African American history is deep-rooted in Illinois. Discover museums that celebrate African American culture and art. Visit the sites where freedom Jacksonville seekers traveled along the Underground Railroad. Indulge in Springfield 3–5 days African American culture through flavorful food and soulful music. Wherever you explore, Illinois welcomes you to 321mi (Approx) embrace the powerful legacy of its African American roots. Alton African American History Black Ensemble Theater African American Cultural Center The Art Institute of Chicago Many places have reopened with limited capacity, new operating hours or other restrictions. Kingston Mines Inquire ahead of time for up-to-date health and safety information. Day 1 Downtown Chicago in Dr. Murphy’s Food Hall. Finally, get your fill of blues and jazz at various lounges across Chicago’s African American community has had a the city, such as Buddy Guy’s Legends, major impact on both American and global culture, Kingston Mines, Andy’s Jazz Club and the so there’s no better place to start your exploration Green Mill Cocktail Lounge. Courtesy of than downtown Chicago. Start the morning at the Kevin J. Miyasaki/Redux Jean Baptiste Pointe DuSable bust on Michigan Overnight in one of the hotels near Avenue; the Haitian-born fur trader is recognized as McCormick Place like the Hyatt Regency, Bronzeville Neighborhood the founder of Chicago. Hilton Garden Inn and Hampton Inn. Other options include The Sophy Hyde Park and The Blackstone Make your way to the Art Institute of Chicago, across from Grant Park. -

Lincoln, Abraham— Miscellaneous Publications Collection

McLean County Museum of History Lincoln, Abraham— Miscellaneous Publications Collection Collection Information VOLUME OF COLLECTION: 2 boxes COLLECTION DATES: 1860-2009 RESTRICTIONS: None REPRODUCTION RIGHTS: Permission to reproduce or publish material in this collection must be obtained in writing from the McLean County Museum of History ALTERNATIVE FORMATS: None OTHER FINDING AIDS: None LOCATION: Archives NOTES: None Box and Folder Inventory Box 1 Folder 1: Lincoln Autobiographies 1.1.1 Appleman, Roy Edgar, ed. Abraham Lincoln From His Own Words and Contemporary Accounts. National Park Service. Source Book Series. Number Two. GPO, Washington, D.C., 1942 (revised 1956).C. & A. Athletes, Balle’s Orchestra, March 14, 1905 1.1.2 Sage, Harold K. Jesse W. Fell and the Lincoln Autobiography. Bloomington: The Original Smith Printing Co, 1971. Folder 2: Lincoln Comic Books 1.2.1 Classics Illustrated. Abraham Lincoln. No.142. New York: Gilberton Company Inc, 1967. 1.2.2 “All Aboard Mr. Lincoln” Washington: Association of American Railroad, 1959. Folder 3: Biographies 1.3.1 Cameron, W.J. Lincoln. Chicago Historical Society, 1911. 1.3.2 Neis, Anna Marie. Lincoln. Boston: George H. Ellis Company, 1915. 1.3.3 Newman, Ralph G. Lincoln. Lincoln: George W. Stewart Publisher Inc, 1958. 1.3.4 Pierson, A.V. Lincoln and Grant. n.p., n.d. 1.3.5 Young, James C. “Lincoln and His Pictures.” The New York Times Book Review and Magazine (New York, NY), February 12, 1922. 1.3.6 The Board of Temperance of the Methodist Church. “Abraham Lincoln” The Voice, February 1949. 1.3.7 “The Wanamaker Primer on Abraham Lincoln” Lincoln Centenary, 1909. -

Schedule of Events

Schedule of Events Tuesdays 9 am - 5 pm: Period Characters | Lincoln's New Salem June 5 - A 10 am: WHB - Design Like Frank Lloyd Wright Drawing Tour ugust 7, 202 7 pm: Flag Lowering Ceremony | Lincoln Tomb 1 7:30 pm: Lincoln's Ghost Walk $ Wednesdays 9 am - 5 pm: Period Characters | Lincoln's New Salem Saturdays 10 am: WHB - Friends of Lincoln Hike 9 am - 5 pm: Period Characters | Lincoln's New Salem 10 am: WHB - History Bike Tour | 8 miles 10:30 am: WHB -1908 Race Riot Walking Tour 1 pm: WHB - History Bike Tour | 5 House/5 miles 10:30 am: Springfield Municipal Band Performance | ALPLM 6:30 pm: Themed Concerts | Thomas Rees Memorial Carillon (June 26 & July 17 only) 7:30 pm: Lincoln's Ghost Walk $ 10:30 am: Ulysses S. Grant | ALPLM (June 12, July 3, 10, 24, 31 only) Thursdays Noon: Springfield Walks Springfield's History Mystery Walk 1 pm: Meet Lincoln | Lincoln Home 9 am - 5 pm: Period Characters | Lincoln's New Salem 1:30 pm: Experiencing African American History | Springfield & Central 10:30 am: WHB - 1908 Race Riot Walking Tour IL African American History Museum 1 pm: WHB - Military History Hike 2 pm: Meet Lincoln & Mary | ALPLM $ 2 pm: Illinois Militia & National Guard Heritage | Illinois State 4 pm: Meet Lincoln & Mary | Lincoln Home Military Museum 5 pm: 1860s Party on the Plaza | Old State Capitol Grounds 7:30 pm: Lincoln's Ghost Walk $ 7:30 pm: Lincoln's Ghost Walk $ (Don't miss the Levitt Amp Springfield Concerts, see page 2 for info) Fridays Walk Hike Bike Tours = WHB Admission = $ Abraham Lincoln Presidential Museum = ALPLM Mr. -

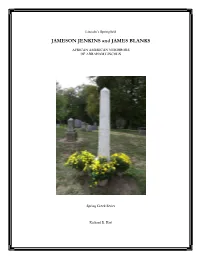

JAMESON JENKINS and JAMES BLANKS

Lincoln’s Springfield JAMESON JENKINS and JAMES BLANKS AFRICAN AMERICAN NEIGHBORS OF ABRAHAM LINCOLN Spring Creek Series Richard E. Hart Jameson Jenkins’ Certificate of Freedom 1 Recorded With the Recorder of Deeds of Sangamon County, Illinois on March 28, 1846 1 Sangamon County Recorder of Deeds, Deed Record Book 4, p. 21, Deed Book AA, pp. 284-285. Jameson Jenkins and James Blanks Front Cover Photograph: Obelisk marker for graves of Jameson Jenkins and James Blanks in the “Colored Section” of Oak Ridge Cemetery, Springfield, Illinois. This photograph was taken on September 30, 2012, by Donna Catlin on the occasion of the rededication of the restored grave marker. Back Cover Photograph: Photograph looking north on Eighth Street toward the Lincoln Home at Eighth and Jackson streets from the right of way in front of the lot where the house of Jameson Jenkins stood. Dedicated to Nellie Holland and Dorothy Spencer The Springfield and Central Illinois African American History Museum is a not-for-profit organization founded in February, 2006, for the purpose of gathering, interpreting and exhibiting the history of Springfield and Central Illinois African Americans life in the 19th, 20th and 21st centuries. We invite you to become a part of this important documentation of a people’s history through a membership or financial contribution. You will help tell the stories that create harmony, respect and understanding. All proceeds from the sale of this pamphlet will benefit The Springfield and Central Illinois African American History Museum. Jameson Jenkins and James Blanks: African American Neighbors of Abraham Lincoln Spring Creek Series. -

Economic Impacts of the Proposed Pullman National Historical Park

FINAL REPORT Economic Impacts of the Proposed Pullman National Historical Park Submitted To: National Parks Conservation Association August 2, 2013 MFA Project Number 548 Executive Summary The National Parks Conservation Association (“NPCA” or “Client”) retained Market Feasibility Advisors, LLC (“MFA”) to assess the economic impacts of the potential designation of the historic Pullman neighborhood as a Pullman National Historical Park (“Park”) by the National Park Service (“NPS”). Pullman is a Chicago neighborhood located approximately 15 miles due south of downtown. It appears that the Pullman Historic District features all the attributes necessary to be designated as a unit of the National Park System, an action that could greatly enhance the revitalization of the area and preserve the architectural and cultural heritage that makes it such a historical treasure. Pullman showcases 19th and 20th Century industrial society with unique stories of architecture, labor history— including formation of the first African-American labor union, landscape design, urban planning, and transportation history. The convergence of multiple stories of undisputed national significance makes Pullman worthy of national park status. As an example of vertical integration, Pullman was only surpassed by Henry Ford’s River Rouge complex, presenting a historical model of corporate structure very much emulated in today’s world. Pullman offers ample opportunities for public use and enjoyment, in an environment rich in history. The economic impacts of the proposed National Historical Park designation would vary greatly depending on the specific actions taken in regards to that designation. It is MFA’s understanding that at this time NPS has not created any plans, let any contracts, or partnered with any concessionaires to operate anything in Pullman. -

Lincoln's New Salem, Reconstructed

Lincoln’s New Salem, Reconstructed MARK B. POHLAD “Not a building, scarcely a stone” In his classic Lincoln’s New Salem (1934), Benjamin P. Thomas observed bluntly, “By 1840 New Salem had ceased to exist.”1 A century later, however, a restored New Salem was—after the Lincoln Memorial, in Washington, D.C.—the most visited Lincoln site in the world. How this transformation occurred is a fascinating story, one that should be retold, especially now, when action must be taken to rescue the present New Salem from a grave decline. Even apart from its connection to Abraham Lincoln, New Salem is like no other reconstructed pioneer village that exists today. Years before the present restoration occurred, planners aimed for a unique destination. A 1920s state-of- Illinois brochure claimed that once the twenty- five original structures were rebuilt on their original founda- tions, it would be “the only known city in the world that has ever been restored in its entirety.”2 In truth, it is today the world’s largest log- house village reconstructed on its original site and on its build- ings’ original foundations. It is still startling nearly two hundred years later that a town of more than a hundred souls—about the same number as lived in Chicago at that time—existed for only a decade. But such was the velocity of development in the American West. “Petersburg . took the wind out of its sails,” a newspaperman quipped in 1884, because a new county seat and post office had been established there; Lincoln himself had surveyed it.3 Now the very buildings of his New Salem friends and 1. -

Life of Lincoln Tour

Earn 12 SCECHs with this tour! Attention educators! SCECHs Michigan Council for the Social Studies Life of Lincoln Tour July 27-30, 2018 Join the Historical Society of Michigan and the Michigan Council for the Social Studies for a 4-day, 3-night tour Experience the areas Tour Illinois’ picturesque of Lincoln’s Abraham Lincoln called home! Old State Capitol! life in Illinois! $625* Explore New Salem, where Lincoln lived as a young man! Enjoy a guided tour of Lincoln’s home! And So Much More... To register for this tour, call (800) 692-1828 or visit hsmichigan.org/programs * Includes motor coach transportation; all lodging; all dinners and breakfasts, plus one boxed lunch on the motor coach; and all admission fees, taxes, and gratuities. Membership in either the Historical Society of Michigan OR the Michigan Council for the Social Studies is required. Price is per person based on double occupancy. Experience an in-depth look at the life of one of America’s greatest presidents with our “Life of Lincoln” motor coach tour. The 4-day, 3-night tour includes a special visit to the new Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum in Springfield, Illinois. We’ll also tour Lincoln’s New Salem State Historic Site, the Lincoln Home in Springfield, the Lincoln Tomb in Oak Ridge Cemetery, and much more! Your guide will be Robert Myers, our Assistant Director for Education Programs and Events. Like all of our tours, we’ve planned every detail ourselves—no “off the rack” tours for us! We depart the Historical Society of Michigan oces in Lansing bright and early aboard a Great Lakes Transportation Company motor coach, stopping at two convenient Michigan Day 1 Department of Transportation Park and Ride lots in Portage and Stevensville to pick up a few of our remaining members. -

Review Essay

Review Essay THOMAS R. TURNER Thomas J. Craughwell. Stealing Lincoln’s Body. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 2007. Pp. 250. In a story about Thomas J. Craughwell’s Stealing Lincoln’s Body on the CNN.com Web site, Bob Bender, senior editor of Simon and Schuster, notes that Abraham Lincoln has been a best-selling subject, probably since the month after he died. While Lincoln scholars have occasion- ally agonized that there is nothing new to be said about Lincoln— witness James G. Randall’s 1936 American Historical Review article, “Has the Lincoln Theme Been Exhausted?”—books about the sixteenth president continue to pour forth unabated. (This soul searching seems unique to the Lincoln field; one is hard put to think of another research field where scholars raise similar concerns.) If anything, the pace may be accelerating, with the approaching bicentennial of Lincoln’s birth in 2009 calling renewed attention to all facets of his life and career. Bender also cites the old adage that, in the publishing world, books on animals, medicine, and Lincoln are always guaranteed best-sellers. George Stevens in 1939 published a book titled Lincoln’s Doctor’s Dog & Other Famous Best Sellers, and in 2001 Richard Grayson produced a work with a similar title. Neither book sold many copies; Grayson’s sold fewer than two hundred, causing him to write “The only thing I can come up with is that Lincoln isn’t as popular as he used to be.” Given the limitations on press budgets, the number of copies of a book that must be sold to make a profit, a decline in the number of Lincoln collectors, and severe restrictions on library budgets, Grayson may be correct: merely publishing a Lincoln book is no longer a guar- antee of financial success. -

Custodians at Lincoln's Tomb John Carroll Power Edward S

LINCOLN LORE Bulletin of the Lincoln National Life Foundation ------ Dr. Lona A. Warren Editor Published each week by The Lincoln National Life Insurance Company, Fort Wayne, fudiana Number 1078 FORT WAYNE, INDIANA December 5, 1949 CUSTODIANS AT LINCOLN'S TOMB JOHN CARROLL POWER EDWARD S. JOHNSON HERBERT WELLS FAY 1874-1894, 20 years 1895-1920, 25 years 1921-1949, 28 years The first full time custodian of the A native of Springfield Illinois, Bringing to a proper clin1ax this Lincoln Tomb at Springfield, lllinois Edward S. Johnson became the sec most remarkable exhibition of fidelity, was John C. Power. He was born in ond custodian at the Lincoln Tomb. stamina and enterprise in this three Fleming County Kentucky on Sep He was born August 9, 1843 and with man public service succession ex_... tember 19, 1819, but did not come into the exception of the years spent in tending over 73 years, Herbert Wells prominence as an authority in the military sernce and a short time in Fay, labored long<ll' and lived longer Lincoln field until he became associ Chicago, resided in the city all his than either of his two predecessors. ated with the Springfield Board of life. His father and Abraham Lincoln This issue of Lincoln Lore is most Trade. In 1871 he published for that were close friend'!, and Edward John sincerely dedicated to his memory, not organization a History of S'(YI'ingfield. son and Robert Lincoln were school only for his long and faithful service, The last four pages ot the history mates-but eight days separating but for his unusual enthusiasm for were utilized in telling ~ the story of their respective births. -

Life of Lincoln Tour

Life of Lincoln Tour October 13-16, 2017 Join the Historical Society of Michigan’s “Michiganders on the Road” for a 4-day, 3-night tour of Lincoln’s life in Illinois! $625* To register for this tour, call (800) 692-1828 or visit hsmichigan.org/programs * Includes motor coach transportation; all lodging; all dinners and breakfasts, plus one boxed lunch on the motor coach; and all admission fees, taxes, and gratuities. Historical Society of Michigan membership required; memberships start at $25. Price is per person based on double occupancy. Experience an in-depth look at the life of one of America’s greatest presidents with our “Life of Lincoln” motor coach tour. The 4-day, 3-night tour includes a special visit to the new Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum in Springfield, Illinois. We’ll also tour Lincoln’s New Salem State Historic Site, the Lincoln Home in Springfield, the Lincoln Tomb in Oak Ridge Cemetery, and much more! Your guide will be Robert Myers, our Assistant Director for Education Programs and Events. Like all of our tours, we’ve planned every detail ourselves—no “off the rack” tours for us! We depart the Historical Society of Michigan offices in Lansing bright and early aboard a Compass motor coach, stopping at two convenient Michigan Department of Transportation Day 1 Park and Ride lots along the way to pick up a few of our remaining members. Heading through miles of cornfields in central Illinois, the prairie’s gorgeous vistas open up into another spectacular…cornfield. All right, we have to confess that the drive to Lincoln country isn’t the most exciting one in America, but we can watch a movie on the coach’s DVD system, play one of Bob’s Useless Trivia Games, or just take a morning nap. -

Lincoln S New Salem State Historic Site Invites You & Your Family to The

Lincoln’s New Salem State Historic Site Welcomes You Lincoln s New Salem State Historic Site invites you & your family to the Reunion of Direct Descendants of the New Salem Community Saturday, July 8, 2006 Lincoln’s New Salem State Historic Site Petersburg, Illinois The 2006 Lincoln’s Landing events celebrate the 175th anniversary of Abraham Lincoln’s arrival at New Salem July 8, 2006, is the Reunion of Direct Descendants of New Salem. Direct descendants will be recognized as special guests of New Salem and the Illinois Historical Preservation Agency. Descendants, relatives, friends, and visitors are invited to enjoy many special activities. Some descendant families have scheduled reunions in the area this weekend, and many participants are coming great distances to attend. We are happy to welcome everyone to New Salem. Please check in with us at the Descendant’s Registration Desk at the Visitors Center. Enjoy meeting new relatives and sharing your family history with family, friends, and the site. The contact for this event is Event Chair Barbara Archer, who may be reached at 217- 546-4809 or [email protected] for further information and details. To reach New Salem from Springfield, follow Route 125 (Jefferson Street) to Route 97 (about 12 miles west), turn right at the brown New Salem sign; travel 12 miles to the site entrance. From Chicago, exit Interstate 55 at the Williamsville Exit 109 and follow the signs or take the Springfield Clear Lake Exit 98; Clear Lake becomes Route 125. From St. Louis, take 55 Exit 92 to Route 72 west; exit 72 at Route 4/Veterans Parkway Exit 93; take Veterans Parkway north to Route 125; turn left. -

Richard Carwardine — 2018 Annual Banquet Speaker

FOR THE PEOPLE NEWSLETTER OF THE ABRAHAM LINCOLN ASSOCIATION 1 F O R T H E P E O P L E A NEWSLETTER OF THE ABRAHAM LINCOLN ASSOCIATION http://www.abrahamlincolnassociation.org VOLUME 19 NUMBER 4 WINTER 2017 SPRINGFIELD, ILLINOIS Richard Carwardine — 2018 Annual Banquet Speaker As an undergraduate at Corpus Christi His analytical biography of Abraham College, Oxford, in the 1960s, Richard Lincoln won the Lincoln Prize in 2004 and Carwardine took his BA in Modern History. was subsequently published in the United After graduation, he took up the Ochs- States as Lincoln: A Life of Purpose and Oakes Graduate Scholarship in American Power (Knopf, 2006). History at The Queen's College, Oxford; he spent a year at the University of California, In July 2009, as an adviser to the Abraham Berkeley, during an era of campus Lincoln Bicentennial Commission, he convulsions (1969-70). convened an international conference in Oxford to examine Abraham Lincoln's global legacy. The proceedings appeared as Dr. Carwardine taught American History at The Global Lincoln (Oxford University the University of Sheffield from 1971 to Press, 2011), co-edited with Jay Sexton. 2002, serving a term as Dean of the Faculty of Arts. From 2002 to 2009 he was Rhodes His most recent book,Lincoln’s Sense of Professor of American History and Humor (Southern Illinois University Press), Institutions at Oxford University, and a was published in November 2017. Fellow of St. Catherine's College. In 2010, he returned to Corpus Christi College, He is currently working on a book for Oxford, as President, serving until his Alfred A.