The Sochi Olympics, Celebration Capitalism and Homonationalist Pride1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Italian Debate on Civil Unions and Same-Sex Parenthood: the Disappearance of Lesbians, Lesbian Mothers, and Mothers Daniela Danna

The Italian Debate on Civil Unions and Same-Sex Parenthood: The Disappearance of Lesbians, Lesbian Mothers, and Mothers Daniela Danna How to cite Danna, D. (2018). The Italian Debate on Civil Unions and Same-Sex Parenthood: The Disappearance of Lesbians, Lesbian Mothers, and Mothers. [Italian Sociological Review, 8 (2), 285-308] Retrieved from [http://dx.doi.org/10.13136/isr.v8i2.238] [DOI: 10.13136/isr.v8i2.238] 1. Author information Daniela Danna Department of Social and Political Science, University of Milan, Italy 2. Author e-mail address Daniela Danna E-mail: [email protected] 3. Article accepted for publication Date: February 2018 Additional information about Italian Sociological Review can be found at: About ISR-Editorial Board-Manuscript submission The Italian Debate on Civil Unions and Same-Sex Parenthood: The Disappearance of Lesbians, Lesbian Mothers, and Mothers Daniela Danna* Corresponding author: Daniela Danna E-mail: [email protected] Abstract This article presents the political debate on the legal recognition of same-sex couples and same-sex parenthood in Italy. It focuses on written sources such as documents and historiography of the LGBT movement (so called since the time of the World Pride 2000 event in Rome), and a press review covering the years 2013- 2016. The aim of this reconstruction is to show if and how sexual difference, rather important in matters of procreation, has been talked about within this context. The overwhelming majority of same-sex parents in couples are lesbians, but, as will be shown, lesbians have been seldom mentioned in the debate (main source: a press survey). -

An Ethnographic Account of Disability and Globalization in Contemporary Russia

INACCESSIBLE ACCESSIBILITY: AN ETHNOGRAPHIC ACCOUNT OF DISABILITY AND GLOBALIZATION IN CONTEMPORARY RUSSIA Cassandra Hartblay A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Anthropology. Chapel Hill 2015 ! ! ! ! Approved by: Michele Rivkin-Fish Arturo Escobar Sue Estroff Jocelyn Chua Robert McRuer © 2015 Cassandra Hartblay ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ! ii! ABSTRACT Cassandra Hartblay: Inaccessible Accessibility: An Ethnographic Account Of Disability And Globalization In Contemporary Russia (Under the Direction of Michele Rivkin-Fish) Based on over twelve months of fieldwork in Russia, this dissertation explores what an ethnographic approach offers disability studies as a global, interdisciplinary, justice-oriented field. Focused on the personal, embodied narratives and experiences of five adults with mobility impairments in the regional capital city of Petrozavodsk, the dissertation draws on methods including participant observation, ethnographic interviews, performance ethnography, and analysis of public documents and popular media to trace the ways in which the category of disability is reproduced, stigmatized, and made meaningful in a contemporary postsoviet urban context. In tracing the ways in which concepts of disability and accessibility move transnational and transculturally as part of global expert cultures, I argue that Russian adults with disabilities expertly negotiate multiple modes of understanding disability, including historically and culturally rooted social stigma; psychosocial, therapeutic, or medicalized approaches; and democratic minority group citizenship. Considering the array of colloquial Russian terms that my interlocutors used to discuss issues of access and inaccess in informal settings, and their cultural antecedents, I suggest that the postsoviet infrastructural milieu is frequently posited as always opposed to development and European modernity. -

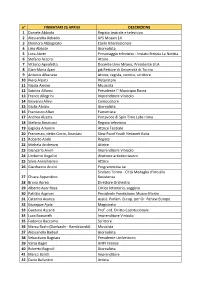

Firmatari Appello 25Aprile.Pdf

n° FIRMATARI 25 APRILE DESCRIZIONE 1 Daniele Abbado Regista teatrale e televisivo 2 Alessandra Abbado APS Mozart 14 3 Eleonora Abbagnato Etoile Internazionale 4 Lirio Abbate Giornalista 5 Luca Abete Personaggio televisivo - Inviato Striscia La Notizia 6 Stefano Accorsi Attore 7 Vittorio Agnoletto Docente Univ Milano, Presidente LILA 8 Gian Maria Ajani già Rettore di Università di Torino 9 Antonio Albanese Attore, regista, comico, scrittore 10 Piero Alciati Ristoratore 11 Nicola Alesini Musicista 12 Sabrina Alfonsi Presidente I° Municipio Roma 13 Franco Allegrini Imprenditore Vinicolo 14 Giovanni Allevi Compositore 15 Giulia Aloisio Giornalista 16 Francesco Altan Fumettista 17 Andrea Alzetta Portavoce di Spin Time Labs roma 18 Stefano Amatucci Regista televisivo 19 Gigliola Amonini Attrice Teatrale 20 Francesco, detto Ciccio, Anastasi Slow Food Youth Network Italia 21 Roberto Andò Regista 22 Michela Andreozzi Attrice 23 Giancarlo Aneri Imprenditore Vinicolo 24 Umberto Angelini direttore artistico teatro 25 Silvia Annichiarico Attrice 26 Gianfranco Anzini Programmista rai Sindaco Torino - Città Medaglia d'oro alla 27 Chiara Appendino Resistenza 28 Bruno Aprea Direttore Orchestra 29 Alberto Asor Rosa Critico letterario, saggista 30 Patrizia Asproni Presidente Fondazione Museo Marini 31 Caterina Avanza Assist. Parlam. Europ. per Gr. Renew Europe 32 Giuseppe Ajala Magistrato 33 Gaetano Azzariti Prof. ord. Diritto Costituzionale 34 Luca Baccarelli Imprenditore Vinicolo 35 Federico Baccomo Scrittore 36 Marco Bachi (Donbachi - Bandabardò) Musicista -

Print Version of the Zine

Who is QAIA? (cont’d from inside front cover) New York City Queers Against Israeli Apartheid (NYC-QAIA) is a group of queer activists who support MAY 24-25 NYC QAIA and QFOLC invites queers and allies to a meeting in the lobby of the Center. The Center Palestinians’ right to self-determination, and challenge Israel’s occupation of the West Bank & East Jeru- approves a QAIA request for space for a few meetings. Michael Lucas threatens for a boycott of city salem as well as the military blockade of Gaza. We stand with Palestinian civil society’s call for boycott, funding of the Center. divestment and sanctions (BDS) against Israel, and the call by Palestinian queer groups to end the oc- cupation as a critical step for securing Palestinian human rights as well as furthering the movement for Palestinian queer rights. Check out QAIA: MAY 26 QAIA’s meeting takes place in Room 412 instead of the lobby. Planning proceeds for QAIA’s pride http://queersagainstisraeliapartheid.blogspot.com contingents. A meeting is scheduled for June 8. What is PINKWASHING & PINKWATCHING anyway? JUNE QAIA participates in Queens & Brooklyn Pride Parades, Trans Day of Action, Dyke March, and NYC “Pinkwashing” is attempts by some supporters of Israel to defend Israeli occupation and apartheid by LGBT Pride March in Manhattan, eliciting positive responses in all; but one group of pro-Palestinian diverting attention to Israel’s supposedly good record on LGBT rights. Anti-pinkwashing is pinkwatch- queers with a different contingent is pushed and shoved by a pro-Israel contingent. ing. Pinkwatching activists (like NYC-QAIA) work to expose Israeli pinkwashing tactics and counter them through our messaging that queer struggle globally is not possible until there is liberation for all JUNE 2 people, and that Israel being washed as a gay-haven instead of an Apartheid settler state is unjustly The Center announces a ban on Palestine solidarity organizing and a moratorium on discussion of saying: human rights for some, not all. -

M Franchi Thesis for Library

The London School of Economics and Political Science Mediated tensions: Italian newspapers and the legal recognition of de facto unions Marina Franchi A thesis submitted to the Gender Institute of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, May 2015 1 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 88924 words. Statement of use of third party for editorial help (if applicable) I can confirm that my thesis was copy edited for conventions of language, spelling and grammar by Hilary Wright 2 Abstract The recognition of rights to couples outside the institution of marriage has been, and still is, a contentious issue in Italian Politics. Normative notions of family and kinship perpetuate the exclusion of those who do not conform to the heterosexual norm. At the same time the increased visibility of kinship arrangements that evade the heterosexual script and their claims for legal recognition, expose the fragility and the constructedness of heteronorms. During the Prodi II Government (2006-2008) the possibility of a law recognising legal status to de facto unions stirred a major controversy in which the conservative political forces and the Catholic hierarchies opposed any form of recognition, with particular acrimony shown toward same sex couples. -

Italy and the Regulation of Same-Sex Unions Alessia Donà*

Modern Italy, 2021 Vol. 26, No. 3, 261–274, doi:10.1017/mit.2021.28 Somewhere over the rainbow: Italy and the regulation of same-sex unions Alessia Donà* Department of Sociology and Social Research, University of Trento, Italy (Received 11 August 2020; final version accepted 6 April 2021) While almost all European democracies from the 1980s started to accord legal recogni- tion to same-sex couples, Italy was, in 2016, the last West European country to adopt a regulation, after a tortuous path. Why was Italy such a latecomer? What kind of barriers were encountered by the legislative process? What were the factors behind the policy change? To answer these questions, this article first discusses current morality policy- making, paying specific attention to the literature dealing with same-sex partnerships. Second, it provides a reconstruction of the Italian policy trajectory, from the entrance of the issue into political debate until the enactment of the civil union law, by considering both partisan and societal actors for and against the legislative initiative. The article argues that the Italian progress towards the regulation of same-sex unions depended on the balance of power between change and blocking coalitions and their degree of congru- ence during the policymaking process. In 2016 the government formed a broad consen- sus and the parliament passed a law on civil unions. However, the new law represented only a small departure from the status quo due to the low congruence between actors within the change coalition. Keywords: same-sex unions; party politics; morality politics; LGBT mobilisation; Catholic Church; veto players. -

Belgium to Introduce ‘X’ As Third, Non-Binary Gender • Belgium’S De Sutter Breaks New Ground for Transgender Politicians

Table of Contents • Belgium to introduce ‘X’ as third, non-binary gender • Belgium’s De Sutter breaks new ground for transgender politicians Belgium to introduce ‘X’ as third, non-binary gender By Gabriela Galindo The Brussels Times (09.11.2020) - https://bit.ly/36wunXk - Belgium’s new government will introduce gender-neutrality throughout its term and make it possible for non-binary citizens to use the gender identifier “X.” Federal Justice Minister Vincent Van Quickenborne said gender inclusion and self- determination will be one of the policies he will work on throughout his tenure, according to a general policy note released last week. Van Quickenborne’s note follows a Constitutional Court ruling last year which said Belgium’s law on transgender people should be made more inclusive, the Belga news agency reports. The court found that the law, which was passed in 2017 to allow people to modify the gender assigned to them at birth, needlessly maintained binary masculine and feminine genders, making it restrictive and discriminatory. It therefore ruled that the law must take into account a person’s right to self-determination. The justice minister said that his cabinet would push modifications of the law in parliament to “make [the law] on gender registration conform with the court’s decision.” Van Quickenborne said the changes in question were “an ethically sensible issue” and said he hoped the debate could take place “in an open and flexible way” in parliament, where it would face lawmakers from the conservative fringes, such as the N-VA and the Vlaams Belang (VB) as well as his party’s coalition partner, the Flemish CD&V. -

LEVELS of GENERALITY and the PROTECTION of LGBT RIGHTS BEFORE the UNITED NATIONS GENERAL ASSEMBLY Anthony S. Winert

LEVELS OF GENERALITY AND THE PROTECTION OF LGBT RIGHTS BEFORE THE UNITED NATIONS GENERAL ASSEMBLY Anthony S. Winert I. INTRODUCTION .................................................................... 81 II. THE SIGNIFICANCE OF GENERAL ASSEMBLY RESOLUTIONS FOR INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS ................................. 82 A. The Position of the GeneralAssembly in the United N ations .......................................................................... 83 B. The Record of GeneralAssembly Resolutions in Advancing H um an Rights................................................................. 86 III. THE POWER OF LEVELS OF GENERALITY .................................. 91 A. Levels of GeneralityDescribing Rights................................... 92 B. United States Supreme Court Perspective on Levels of Generality ...................................................................... 93 C. A Prominent Illustrationfor the Importance of Levels of Generality ...................................................................... 96 D. A Variant-FormSense of Generality ................................. 99 IV. LEVELS OF GENERALITY AND THE INTERNATIONAL ADVANCEMENT OF LGBT RIGHTS .......................................... 100 A. Key Recent Developments ................................................... 101 B. The Yogyakarta Principles................................................. 102 C. The United Nations High Commissionerfor Human Rights ............................................................................... 104 1. Office of -

Human Rights in Russia: Challenges in the 21St Century ICRP Human Rights Issues Series | 2014

Institute for Cultural Relations Policy Human Rights Issues Series | 2014 ICRP Human Rights Issues Series | 2014 Human rights in Russia: Challenges in the 21st century ICRP Human Rights Issues Series | 2014 Human rights in Russia: Challenges in the 21st century Author | Marija Petrović Series Editor | András Lőrincz Published by | Institute for Cultural Relations Policy Executive Publisher | Csilla Morauszki ICRP Geopolitika Kft., 1131 Budapest, Gyöngyösi u. 45. http://culturalrelations.org [email protected] HU ISSN 2064-2202 Contents Foreword 1 Introduction 2 Human rights in the Soviet Union 3 Laws and conventions on human rights 5 Juridical system of Russia 6 Human rights policy of the Putin regime 8 Corruption 10 Freedom of press and suspicious death cases 13 Foreign agent law 18 The homosexual question 20 Greenpeace activists arrested 24 Xenophobia 27 North Caucasus 31 The Sochi Olympics 36 10 facts about Russia’s human rights situation 40 For further information 41 Human rights in Russia: Challenges in the 21st century Human rights in Russia: Challenges in the 21st century Foreword Before presenting the human rights situation in Russia, it is important to note that the Institute for Cultural Relations Policy is a politically independent organisation. This essay was not created for condemning, nor for supporting the views of any country or political party. The only aim is to give a better understanding on the topic. On the next pages the most important and mainly most current aspects of the issue are examined, presenting the history and the present of the human rights situation in the Soviet Union and in Russia, including international opinions as well. -

The Debate About Same-Sex Marriages/Civil Unions in Italy’S 2006 and 2013 Electoral Campaigns

AperTO - Archivio Istituzionale Open Access dell'Università di Torino The debate about same-sex marriages/civil unions in Italy’s 2006 and 2013 electoral campaigns This is the author's manuscript Original Citation: Availability: This version is available http://hdl.handle.net/2318/1526017 since 2021-03-12T15:21:20Z Published version: DOI:10.1080/23248823.2015.1041250 Terms of use: Open Access Anyone can freely access the full text of works made available as "Open Access". Works made available under a Creative Commons license can be used according to the terms and conditions of said license. Use of all other works requires consent of the right holder (author or publisher) if not exempted from copyright protection by the applicable law. (Article begins on next page) 27 September 2021 This is a postprint author version of: Luca Ozzano The debate about same-sex marriages/civil unions in Italy’s 2006 and 2013 electoral campaigns Contemporary Italian Politics Vol. 7, No. 2, pp. 141-160 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/23248823.2015.1041250 Abstract Issues related to lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender rights have for a long time been taboo in Catholic Italy, and they began to be debated in the mainstream media only after the organisation of a gay pride march in Rome during the 2000 jubilee. In the years since, the subject has become a bone of contention between the centre-left and the centre-right parties. In particular, a heated debate developed before and immediately after the 2006 parliamentary elections, when the centre–left coalition included parties – such as the Partito Radicale (Radical Party) and Rifondazione Comunista (Communist Refoundation) – willing to approve a law giving legal recognition to same-sex couples, while, on the other hand, the centre-right relied strongly on ‘traditional values’ in order to garner votes. -

Jennifer Birch-Jones PRIDE Ho

2010 PRIDE house Legacy Report Prepared for: The 2010 PRIDE house Steering Committee Prepared by: Jennifer Birch‐Jones PRIDE house Steering Committee Member and Learning Facilitator November 2010 Acknowledgements The author would like to acknowledge and thank all those who contributed to this Legacy Report, particularly the members of the PRIDE house Steering Committee (See Annex A for a list of Steering Committee Members). In addition, the financial support from the City of Vancouver’s 2010 Legacy Reserve Fund to assist in the review of the project under the "Host A City Happening" program is greatly appreciated. Thanks also to the partners, sponsors, and the many others who contributed to the historic success of the first ever PRIDE house at the 2010 Vancouver Olympic and Paralympic Games. PRIDE house Legacy Report i November 2010 Table of Contents Acknowledgements........................................................................................................................................ i Table of Contents.......................................................................................................................................... ii Introduction ..................................................................................................................................................1 Origins and Objectives ..................................................................................................................................1 Planning Model .............................................................................................................................................3 -

Fear and Loathing in the Iron Closet

FACULTY OF LAW Lund University Simon Andersson Fear and Loathing in the Iron Closet The right to freedom of assembly for LGBT rights activists in the Russian Federation, Ukraine and the Republic of Moldova, and the role of the Moscow Patriarchate in the invention of “gay propaganda” legislation JURM02 Graduate Thesis Master of Laws programme 30 higher education credits Supervisor: Vladislava Stoyanova Semester of graduation: Spring 2019 Psalm 139:14 (ESV) “I praise you, for I am fearfully and wonderfully made. Wonderful are your works; my soul knows it very well.” John 8:31-32 (ESV) “If you abide in my word, you are truly my disciples, and you will know the truth, and the truth will set you free.” Jesus of Nazareth Contents ABSTRACT 1 PREFACE 2 1. INTRODUCTION 4 I. BACKGROUND 4 II. PURPOSE AND RESEARCH QUESTIONS 6 III. PERSPECTIVE 7 IV. METHODOLOGY AND MATERIALS 13 V. DELIMITATIONS 14 VI. CURRENT RESEARCH 15 VII. TERMINOLOGY 15 VIII. DISPOSITION 17 2. INTERNATIONAL LEGISLATION 19 I. THE EUROPEAN CONVENTION ON HUMAN RIGHTS 19 II. THE COUNCIL OF EUROPE AND THE ECTHR 23 3. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND 40 I. THE OCCURRENCE OF MUZHELOZHSTVO 40 IN PRE-PETRINE RUSSIA II. TSAR PETER'S ANTI-SODOMY STATUTE, 40 MASCULINITY IDEALS AND THE EMERGENCE OF HOMOSEXUAL IDENTITIES IN IMPERIAL RUSSIA III. THE EMERGENCE OF SOVIET MASCULINITIES, 41 THE DECRIMINALISATION OF THE IMPERIAL ANTI- SODOMY STATUTE AND THE RECRIMINALISATION OF MUZHELOZHSTVO IN THE SOVIET UNION IV. POST-SOVIET MASCULINITIES, SEXUAL 42 CITIZENSHIP AND DECRIMINALISATION OF HOMOSEXUALITY IN POST-SOVIET RUSSIA, UKRAINE AND MOLDOVA 4. RUSSIAN FEDERATION 46 I.