Sultans' Palaces and Museums in Indonesian Borneo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Revival of Tradition in Indonesian Politics

The Revival of Tradition in Indonesian Politics The Indonesian term adat means ‘custom’ or ‘tradition’, and carries connotations of sedate order and harmony. Yet in recent years it has suddenly become associated with activism, protest and violence. Since the resignation of President Suharto in 1998, diverse indigenous communities and ethnic groups across Indonesia have publicly, vocally, and sometimes violently, demanded the right to implement elements of adat in their home territories. This book investigates the revival of adat in Indonesian politics, identifying its origins, the historical factors that have conditioned it and the reasons for its recent blossoming. The book considers whether the adat revival is a constructive contribution to Indonesia’s new political pluralism or a divisive, dangerous and reactionary force, and examines the implications for the development of democracy, human rights, civility and political stability. It is argued that the current interest in adat is not simply a national offshoot of international discourses on indigenous rights, but also reflects a specifically Indonesian ideological tradition in which land, community and custom provide the normative reference points for political struggles. Whilst campaigns in the name of adat may succeed in redressing injustices with regard to land tenure and helping to preserve local order in troubled times, attempts to create enduring forms of political order based on adat are fraught with dangers. These dangers include the exacerbation of ethnic conflict, the legitimation of social inequality, the denial of individual rights and the diversion of attention away from issues of citizenship, democracy and the rule of law at national level. Overall, this book is a full appraisal of the growing significance of adat in Indonesian politics, and is an important resource for anyone seeking to understand the contemporary Indonesian political landscape. -

Representation of Pluralism in Literary History from Riau Island, Indonesia

Athens Journal of Philology - Volume 6, Issue 2 – Pages 83-104 Representation of Pluralism in Literary History from Riau Island, Indonesia By Mu᾽jizah One kind of the genre in literature is literary history, often called historiography traditional. In 17th--19th century this type of work was commonly found in the Riau Island manuscripts, especially in Pulau Penyengat. This area in ancient times became a scriptorium of Malay manuscripts. Several authors and scribes’ works, such as Raja Haji, Raja Ali Haji, Raja Ibrahim, and Salamah Binti Ambar and a descendant of Encik Ismail bin Datuk Karkun, were found in the region. Their works among others are Tuhafat An-Nafis, Silsilah Melayu, dan Bugis, and Hikayat Negeri Johor. In Indonesia, the manuscripts are kept in the National Library of Indonesia in Jakarta and Indrasakti Foundation in Riau Island. Some manuscripts among others were found in the Leiden University Library and KITLV Library in Netherlands. The historiography is useful to explore the source of historical knowledge, especially in search for understanding the process in the formation of Malay ethnic group with plural identities in Indonesia. The aim is to find representation of pluralism in the past Malay literary history which has contributed and strengthened nationalism. In the study we use qualititative research and descriptive methods of analysis. The research has found that the Malay ethnic group in Indonesia derived from various ethnic groups that integrated and became a nation with pluralities. According to the myth, the Malay ethnic group came from the unity between the upper-world or the angelic world and the under-world depicted as the marriage between Putri Junjung Buih and a human being. -

THE PERCEPTION of COASTAL COMMUNITY of MANGROVES in SULI SUBDISTRICT, LUWU by Bustam Sulaiman

THE PERCEPTION OF COASTAL COMMUNITY OF MANGROVES IN SULI SUBDISTRICT, LUWU by Bustam Sulaiman Submission date: 18-Nov-2019 07:47PM (UTC-0800) Submission ID: 1216836611 File name: LUTFI_2.docx (103.65K) Word count: 4691 Character count: 26032 THE PERCEPTION OF COASTAL COMMUNITY OF MANGROVES IN SULI SUBDISTRICT, LUWU ORIGINALITY REPORT 7% 5% 5% 4% SIMILARITY INDEX INTERNET SOURCES PUBLICATIONS STUDENT PAPERS PRIMARY SOURCES gre.magoosh.com 1 Internet Source 1% report.ipcc.ch 2 Internet Source 1% Tri Joko, Sutrisno Anggoro, Henna Rya Sunoko, 3 % Savitri Rachmawati. "Pesticides Usage in the 1 Soil Quality Degradation Potential in Wanasari Subdistrict, Brebes, Indonesia", Applied and Environmental Soil Science, 2017 Publication Submitted to Southern Illinois University 4 Student Paper <1% Yangfan Li, Xiaoxiang Zhang, Xingxing Zhao, 5 % Shengquan Ma, Huhua Cao, Junkuo Cao. <1 "Assessing spatial vulnerability from rapid urbanization to inform coastal urban regional planning", Ocean & Coastal Management, 2016 Publication "Microorganisms in Saline Environments: 6 Strategies and Functions", Springer Science and Business Media LLC, 2019 <1% Publication Bustam Sulaiman, Azis Nur Bambang, 7 % Mohammad Lutfi. " Mangrove Cultivation ( ) as <1 an Effort for Mangrove Rehabilitation in the Ponds Bare in Belopa, Luwu Regency ", E3S Web of Conferences, 2018 Publication abyiogren.meb.gov.tr 8 Internet Source <1% ufdc.ufl.edu 9 Internet Source <1% ejournal2.undip.ac.id 10 Internet Source <1% Shin Hye Kim, Min Kyung Oh, Ran Namgung, 11 % Mi Jung Park. "Prevalence of 25-hydroxyvitamin <1 D deficiency in Korean adolescents: association with age, season and parental vitamin D status", Public Health Nutrition, 2012 Publication link.springer.com 12 Internet Source <1% worldwidescience.org 13 Internet Source <1% Mohammad Lutfi, Muh Yamin, Mujibu Rahman, 14 % Elisa Ginsel Popang. -

Masyarakat Kesenian Di Indonesia

MASYARAKAT KESENIAN DI INDONESIA Muhammad Takari Frida Deliana Harahap Fadlin Torang Naiborhu Arifni Netriroza Heristina Dewi Penerbit: Studia Kultura, Fakultas Sastra, Universitas Sumatera Utara 2008 1 Cetakan pertama, Juni 2008 MASYARAKAT KESENIAN DI INDONESIA Oleh: Muhammad Takari, Frida Deliana, Fadlin, Torang Naiborhu, Arifni Netriroza, dan Heristina Dewi Hak cipta dilindungi undang-undang All right reserved Dilarang memperbanyak buku ini Sebahagian atau seluruhnya Dalam bentuk apapun juga Tanpa izin tertulis dari penerbit Penerbit: Studia Kultura, Fakultas Sastra, Universitas Sumatera Utara ISSN1412-8586 Dicetak di Medan, Indonesia 2 KATA PENGANTAR Terlebih dahulu kami tim penulis buku Masyarakat Kesenian di Indonesia, mengucapkan puji syukur ke hadirat Tuhan Yang Maha Kuasa, karena atas berkah dan karunia-Nya, kami dapat menyelesaikan penulisan buku ini pada tahun 2008. Adapun cita-cita menulis buku ini, telah lama kami canangkan, sekitar tahun 2005 yang lalu. Namun karena sulitnya mengumpulkan materi-materi yang akan diajangkau, yakni begitu ekstensif dan luasnya bahan yang mesti dicapai, juga materi yang dikaji di bidang kesenian meliputi seni-seni: musik, tari, teater baik yang tradisional. Sementara latar belakang keilmuan kami pun, baik di strata satu dan dua, umumnya adalah terkonsentasi di bidang etnomusikologi dan kajian seni pertunjukan yang juga dengan minat utama musik etnik. Hanya seorang saja yang berlatar belakang akademik antropologi tari. Selain itu, tim kami ini ada dua orang yang berlatar belakang pendidikan strata dua antropologi dan sosiologi. Oleh karenanya latar belakang keilmuan ini, sangat mewarnai apa yang kami tulis dalam buku ini. Adapun materi dalam buku ini memuat tentang konsep apa itu masyarakat, kesenian, dan Indonesia—serta terminologi-terminologi yang berkaitan dengannya seperti: kebudayaan, pranata sosial, dan kelompok sosial. -

Tracing the Maritime Greatness and the Formation of Cosmopolitan Society in South Borneo

JMSNI (Journal of Maritime Studies and National Integration), 3 (2), 71-79 | E-ISSN: 2579-9215 Tracing the Maritime Greatness and the Formation of Cosmopolitan Society in South Borneo Yety Rochwulaningsih,*1 Noor Naelil Masruroh,2 Fanada Sholihah3 1Master and Doctoral Program of History, Faculty of Humanities, Diponegoro University, Indonesia 2Department of History Faculty of Humanities Diponegoro University, Indonesia 3Center for Asian Studies, Faculty of Humanities, Diponegoro University, Indonesia DOI: https://doi.org/10.14710/jmsni.v3i2.6291 Abstract This article examines the triumph of the maritime world of South Borneo and Received: the construction of a cosmopolitan society as a result of the trade diaspora and November 8, 2019 the mobility of nations from various regions. A “liquid” situation has placed Banjarmasin as a maritime emporium in the archipelago which influenced in Accepted: the 17th century. In fact, the expansion of Islam in the 16th to 17th centuries December 8, 2019 in Southeast Asia directly impacted the strengthening of the existing emporium. Thus, for a long time, Banjarmasin people have interacted and even Corresponding Author: integrated with various types of outsiders who came, for example, Javanese, [email protected] Malays, Indians, Bugis, Chinese, Persians, Arabs, British and Dutch. In the context of the maritime world, the people of South Borneo are not only objects of the entry of foreign traders, but are able to become important subjects in trading activities, especially in the pepper trade. The Banjar Sultanate was even able to respond to the needs of pepper at the global level through intensification of pepper cultivation. -

Digest of Other White House Announcements

2414 Administration of William J. Clinton, 1994 Digest of Other In the evening, the President attended an White House Announcements APEC leaders dinner at the Jakarta Conven- tion Center. Following the dinner, he met with President Kim of South Korea and The following list includes the President's public Prime Minister Murayama of Japan. schedule and other items of general interest an- The President announced his intention to nounced by the Office of the Press Secretary and appoint Bonnie Prouty Castrey and Mary not included elsewhere in this issue. Jacksteit to the Federal Service Impasses Panel. 1 November 10 The President announced his intention to The President announced his intention to appoint Benjamin F. Montoya and Richard appoint David H. Swinton, Adele Simmons, H. Truly as members of the Board of Visitors Bobby Charles Simpson, and Chang-Lin of the U.S. Naval Academy. Tien to the National Commission for Em- ployment Policy. November 15 November 11 In the morning, the President went to In the morning, the President and Hillary Bogor, Indonesia, where he attended meet- Clinton traveled to Anchorage, AK. In the ings with APEC leaders at the Istana Bogor. evening, they traveled to Manila, Philippines. Following a luncheon in the afternoon, the November 12 President continued his meetings with APEC In the evening, the President and Hillary leaders at the Istana Bogor. Clinton arrived in Manila, Philippines. November 16 November 13 In the morning, the President met with In the morning, following an arrival cere- President Soeharto of Indonesia at the Istana mony at the Malacanang Palace, the Presi- Merdeka and then participated in a wreath- dent and Hillary Clinton participated in a laying ceremony at the Kalibata National He- wreath-laying ceremony at the Rizal Monu- roes Cemetery. -

Intimacy-Geopolitics of Redd+ Exploring Access & Exclusion in the Forests of Sungai Lamandau, Indonesia

INTIMACY-GEOPOLITICS OF REDD+ EXPLORING ACCESS & EXCLUSION IN THE FORESTS OF SUNGAI LAMANDAU, INDONESIA BY PETER JAMES HOWSON A thesis submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Victoria University of Wellington 2016 To be truly radical is to make hope possible, rather than despair convincing. – Raymond Williams, Sources of Hope, 1989 ABSTRACT Indonesia remains the largest contributor of greenhouse gases from primary forest loss in the world. To reverse the trend, the Government of Indonesia is banking on carbon market mechanisms like the Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation (REDD+) programme. Geographers have made significant progress in detailing the relationships between private and public interests that enable REDD+. Less understood are the materialities of everyday life that constitute the substantive nodes – the bodies, the subjectivities, the practices and discourses – of political tensions and conflicts within Indonesia’s nascent REDD+ implementation framework. Concerns for ‘equity’ rooted within an economistic frame of ‘benefit sharing’ seem to be high on political agendas. Yet, relatively few studies have investigated the basic principles and intimate processes underlying benefit sharing approaches within sites of project implementation. Focussing on Sungai Lamandau, Central Kalimantan as a case study, I consider the powers local actors mobilise to access, and exclude others from the diverse and, at times, elusive set of ‘benefits’ within one ‘community-based’ REDD+ project. Reflecting on over 150 interviews and ten months of ethnographic observations, the exploration provides a timely alternative to overly reductive REDD+ research, which remains focused on links between benefit sharing, safeguards, additionality, monitoring and verification. -

"Memerangi Pandemi" Pantang Menyerah Menghadapi Covid-19

Vo,.,, 'l"'\1 RINDo PEDuu SES SATu AT As1 cov1D: 9" KDRl�DO RINDO PEDULI SESA SATU ATASI C0'11 D "Memerangi Pandemi" Pantang Menyerah Menghadapi Covid-19 •• Table of Contents 01. Table of Contents CSC 53. PT Korindo Ariabima Sari Provides 02. Message from Management Covid-19 Prevention Assistance to RSUD Sultan Imanuddin 03. Message from Editorial Deskk 54. PT KTH Donates Medical Supplies to Prevent Covid-19 Main Stories 54. PT Panbers Jaya Helps in Education for Underprivileged Children 55. Donation of Duck Livestock for People of Papua Korindo Group Distributes 3,500 55. PT KTH Carries Out Fogging in PPEs to Hospitals in Papua Villages inWest Kotawaringin to Prevent 30 Dengue Fever Korindo Group’s Commitment 31. PT Berkat Cipta Abadi Donates 1,000 56. PT TSE Bantu Aktivitas Belajar in Facing Covid-19 Hazmat Suits to Merauke Regency Sekolah Terpencil 04 Government 57. DKM of PT Aspex Kumbong Shares 06. Korindo Group’s Contribution in Facing 32. PT Dongin Prabhawa Donates PPEs to Happiness with 156 Orphans Covid-19 Pandemic Mappi Regional Government 57. Korindo Foundation Gives 08. Korindo Brings the First and Largest 33. Korindo Group Once Again Provides Scholarships to Children of Employees Plasma Plantation in Papua PPE Donation to Boven Digoel Local Government 58. Head of Bogor Social Agency Calls Aspex as Good Example Company Information 34. PT BFI Helps Repair Community’s Main Road 58. PT Bimaruna Jaya’s Efforts in Easing 35. KABS Helps Meeting Needs of the Burdens of 130 Families Regional Hospital in Pangkalan Bun 59. Health Counseling and Supplementary 36. -

Environmental Culture and Nature in South Kalimantan Painting: an Overview of Fine Arts

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, Volume 525 Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Social Sciences Education (ICSSE 2020) Environmental Culture and Nature in South Kalimantan Painting: An Overview of Fine Arts Wisnu Subroto1* Hajriansyah1 1Faculy of Teacher Training and Education, Lambung Mangkurat University, Indonesia *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT South Kalimantan painting has a long history, spanning from the early days of independence, with its character Gusti Sholihin Hasan, to the present day. The cultural atmosphere and natural environment of South Kalimantan have undoubtedly become objects in the works of South Kalimantan painters, from the past to the present, with the various styles of painting they have been pursuing. This research will focus on cultural objects related to the natural environment of South Kalimantan. The natural environment of South Kalimantan consists of at least the Meratus plateau and the banks of the Barito River and its branches. This study used a qualitative approach by directly reviewing the works of South Kalimantan painters that had been previously selected and classified. Through these works the conclusion is, Keywords: The key to painting South Kalimantan, natural environment, cultural objects 1. INTRODUCTION recording light particles falling on an object from time to Modern painting in South Kalimantan began to grow since time [2,3]. the beginning of independence, with Gusti Sholihin Hasan In Indonesia, the painting movement outside the studio, in as the pioneering figure. From Sholihin came a this realm, gained momentum after S. Soedjojono regeneration of South Kalimantan painters, both those who propagated it in an agitative way. -

Kajian Struktur Ragam Hias Ukiran Tradisional Minangkabau Pada

Versi online: JURNAL TITIK IMAJI http://journal.ubm.ac.id/index.php/titik-imaji/ Volume 1 Nomor 1: 54-67, Maret 2018 Hasil Penelitian p-ISSN: 2620-4940 KAJIAN STRUKTUR RAGAM HIAS UKIRAN TRADISIONAL MINANGKABAU PADA ISTANO BASA PAGARUYUNG [Study of traditional decoration structure of Minangkabau traditional carving on Istano Basa Pagaruyung] Khairuzzaky1* 1Program Studi Desain Komunikasi Visual, Universitas Bunda Mulia, Jl. Lodan Raya No. 2 Ancol, Jakarta Utara 14430, Indonesia Diterima: 15 Febuari 2018/Disetujui: 21 Maret 2018 ABSTRACT Preserving cultural heritage is a cultural fortress attempt against the negative external cultural influences that are so rapidly coming as a result of the current global communications flows that are engulfing the world. One form of material cultural heritage is the various "Minangkabau Traditional Decorative Variety" in Rumah Gadang in West Sumatra whose motifs reflect the noble values of the nation. One of the historical heritage buildings of Indonesia that uses Minangkabau traditional carving is Baso Pagaruyung Palace in Batusangkar, West Sumatra. With the process of making expensive carvings into one of the factors causing this culture has started many abandoned. So it needs to be made a study that discusses the variety of ornamental Minangkabau carving into a written scientific work in order to be known by the public to understand the meaning, structure and philosophy. Using descriptive qualitative research method with interactive analysis, consist of three component of analysis that is data reduction, data presentation and conclusion. The results of the study explain the structure of the compensation and symbolic meaning of each pattern of carving motifs used in the five sections within the Baso Pagaruyung Palace ie the roundabout, the door, the ventilation, the ceiling, and the palace foot. -

The Hybrid Aesthetics of the Malay Vernacular: Reinventing Classifications Through the Classicality of South East Asia’S Palatial Forms

International Journal of Recent Technology and Engineering (IJRTE) ISSN: 2277-3878, Volume-8 Issue-1S, May 2019 The Hybrid Aesthetics of the Malay Vernacular: Reinventing Classifications through the Classicality of South East Asia’s Palatial Forms Shireen Jahn Kassim ( PhD), Noorhanita Abdul Majid ( PhD), Harlina Mohd Shariff ( PhD), and Tengku Anis Qarihah construction capabilities. In South East Asian architectural Abstract: The paper attempts to re-enact the framework of the historiographies, stylistic evolvements dichotomise between ‘vernacular’ of Malay architecture while extending the the ‘indigenous’ and the ‘modern’ . Yet there is another face classifications of its vernacular to include a Classical style ; of the ‘vernacular’ which is less mapped but representing the defined as monumental vernacular expressions representing gradual stylistic changes and ‘hybrid’ constructions throughout degree of aesthetic tastes and predispositions of the local the early modernisation period of Malay history which coincides populations. Historians and ethnograsphers have also with its evolvement during the Colonial era. During this era, both remarked a certain silence in the historiographies on the structural, constructional and ornamental skills absorbed aristocrats of 1800s and early 1900s in once-colonised external influences without compromising its vernacular nations such as Malaysia. Yet during this era, it is the principles. Based on a group of case studies of palatial forms – modernization of these leaders of the community which i.e. palaces and aristocratic houses - from the late 19th and early 20th century, Gottfried Semper’s’ anthropological definitions of brought about stylistic trends within the region but expressed the essence of the vernacular is used to categorise combinations within the palatial-monumental typologies of their vernacular of masonry and timber IN these cases, seen as a manifestation architecture . -

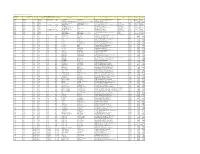

Colgate Palmolive List of Mills As of June 2018 (H1 2018) Direct

Colgate Palmolive List of Mills as of June 2018 (H1 2018) Direct Supplier Second Refiner First Refinery/Aggregator Information Load Port/ Refinery/Aggregator Address Province/ Direct Supplier Supplier Parent Company Refinery/Aggregator Name Mill Company Name Mill Name Country Latitude Longitude Location Location State AgroAmerica Agrocaribe Guatemala Agrocaribe S.A Extractora La Francia Guatemala Extractora Agroaceite Extractora Agroaceite Finca Pensilvania Aldea Los Encuentros, Coatepeque Quetzaltenango. Coatepeque Guatemala 14°33'19.1"N 92°00'20.3"W AgroAmerica Agrocaribe Guatemala Agrocaribe S.A Extractora del Atlantico Guatemala Extractora del Atlantico Extractora del Atlantico km276.5, carretera al Atlantico,Aldea Champona, Morales, izabal Izabal Guatemala 15°35'29.70"N 88°32'40.70"O AgroAmerica Agrocaribe Guatemala Agrocaribe S.A Extractora La Francia Guatemala Extractora La Francia Extractora La Francia km. 243, carretera al Atlantico,Aldea Buena Vista, Morales, izabal Izabal Guatemala 15°28'48.42"N 88°48'6.45" O Oleofinos Oleofinos Mexico Pasternak - - ASOCIACION AGROINDUSTRIAL DE PALMICULTORES DE SABA C.V.Asociacion (ASAPALSA) Agroindustrial de Palmicutores de Saba (ASAPALSA) ALDEA DE ORICA, SABA, COLON Colon HONDURAS 15.54505 -86.180154 Oleofinos Oleofinos Mexico Pasternak - - Cooperativa Agroindustrial de Productores de Palma AceiteraCoopeagropal R.L. (Coopeagropal El Robel R.L.) EL ROBLE, LAUREL, CORREDORES, PUNTARENAS, COSTA RICA Puntarenas Costa Rica 8.4358333 -82.94469444 Oleofinos Oleofinos Mexico Pasternak - - CORPORACIÓN