THE LIFESPAN of CHICKADEES a Thesis Submitted to Kent State

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Moraimde315 Center Street (Rt

y A 24—MANCHESTER HERALD. Friday, April 13, 1990 LEGAL NOTICE DON’T KNOW Where to Is advertising expensive? TOWN OF BOLTON look next for a lob? How I cod CLEANING MISCELLANEOUS ■07 |j MISCELLANEOUS You'll be surprised now I CARS ZONING BOARD OF APPEALS about placing a “Situa 1SERVICES FOR SALE FOR SALE economical It Is to adver FOR SALE Notice is here by given that there will be a public hearing of the tion Wanted" ad In tise In Classified. 643-2711. classified? Zoning Board of >^peals, on Thursday, April 26, 1990 at 7 NO TIM E TO CLEAN. SAFES-New and used. DODGE - 1986. ’150’, 318 p.m. at the Bolton Town Hall, 222 Bolton Center Road, Bolton, Don't really like to END RO LLS Trade up or down. CIO, automatic, bed CT. A clean but hate to come f o o l ROOMMATES 27V4" width — 504 Liberal allowance for WANTED TO liner, tool box, 50K, 1. To hear appeal of Gary Jodoin, 23 Brian Drive for a rear home to a dirty house. I $5500. 742-8669. [ ^ W A N T E D 13" width — 2 for 504 clean safes In good Ibuy/ trade set-back variance for a porch. Coll us 1 We’re reaso condition. American 2. To hear appeal of MIton Hathaway, 40 Quarry Road for a nable and we do a good Newsprint and rolls can bs Graduating? House and picked up at the Manchester Security Corp. Of CT, WANTED: Antiques and special permit to excavate sand & gravel at 40 Quarry Road. -

Baudelaire 525 Released Under Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial Licence

Table des matières Préface i Préface des Fleurs . i Projet de préface pour Les Fleurs du Mal . iii Preface vi Preface to the Flowers . vi III . vii Project on a preface to the Flowers of Evil . viii Préface à cette édition xi L’édition de 1857 . xi L’édition de 1861 . xii “Les Épaves” 1866 . xii L’édition de 1868 . xii Preface to this edition xiv About 1857 version . xiv About 1861 version . xv About 1866 “Les Épaves” . xv About 1868 version . xv Dédicace – Dedication 1 Au Lecteur – To the Reader 2 Spleen et idéal / Spleen and Ideal 9 Bénédiction – Benediction 11 L’Albatros – The Albatross (1861) 19 Élévation – Elevation 22 Correspondances – Correspondences 25 J’aime le souvenir de ces époques nues – I Love to Think of Those Naked Epochs 27 Les Phares – The Beacons 31 La Muse malade – The Sick Muse 35 La Muse vénale – The Venal Muse 37 Le Mauvais Moine – The Bad Monk 39 L’Ennemi – The Enemy 41 Le Guignon – Bad Luck 43 La Vie antérieure – Former Life 45 Bohémiens en voyage - Traveling Gypsies 47 L’Homme et la mer – Man and the Sea 49 Don Juan aux enfers – Don Juan in Hell 51 À Théodore de Banville – To Théodore de Banville (1868) 55 Châtiment de l’Orgueil – Punishment of Pride 57 La Beauté – Beauty 60 L’Idéal – The Ideal 62 La Géante – The Giantess 64 Les Bijoux – The Jewels (1857) 66 Le Masque – The Mask (1861) 69 Hymne à la Beauté – Hymn to Beauty (1861) 73 Parfum exotique – Exotic Perfume 76 La Chevelure – Hair (1861) 78 Je t’adore à l’égal de la voûte nocturne – I Adore You as Much as the Nocturnal Vault.. -

Cleveland CAVALIERS Team Owners: Dan Gilbert, Usher, Gordon Gund Team Website

LEASE SUMMARY TEAM: Cleveland CAVALIERS Team Owners: Dan Gilbert, Usher, Gordon Gund Team Website FACILITY: Quicken Loans Arena Facility Website Year Built: 1994 TITLE OF AGREEMENT: Lease and Management Agreement Lessor: Gateway Economic Development Corporation of Greater Cleveland Lessee: Cavaliers Division of Nationwide Advertising Service, INC. TERM OF AGREEMENT: “The ‘Initial Term’ of this Lease shall commence on the later of (i) the Completion Date, or (ii) the August 1 following the Completion Date in the event that the Completion Date shall occur after October 1 of any year and the Lessee shall elect to defer commencement of its occupancy until the following August 1, and shall end on the one hundred twentieth (120th) day after the last day of the Season either in the year in which the thirtieth (30th) full Season following the first day of the Initial Term is concluded.” Section 5.1, page 50. RENT: “In consideration for the lease of the Arena to the Lessee, the Lessee, on and subject to all of the terms, conditions, and provisions of this Lease, shall pay to Gateway for each Lease Year rent (‘Rent’) at the times and in amounts equal to the following: (a) Within forty-five (45) days after the end of each Reporting Period during the Term, the Lessee shall pay the sum of (i) twenty-seven and one-half percent (27.5%) of the Executive Suite Revenue for such Reporting Period, and (ii) forty-eight percent (48%) of the Club Seat Revenue for such Reporting Period. (b) Within thirty (30) days after the first Reporting Period following each Lease Year, the Lessee shall pay an amount equal to (i) seventy-five cents ($.75) for each Paid Attendance Ticket sold during such Lease Year in excess of one million eight hundred fifty thousand (1,850,000) Paid Attendance Tickets, up to two million five hundred thousand (2,500,000) Paid Attendance Tickets, plus (ii) one dollar ($1.00) for each Paid Attendance Ticket sold during such Lease Year in excess of two million five hundred thousand (2,500,000) Paid Attendance Tickets. -

Butterflies and Moths of Brevard County, Florida, United States

Heliothis ononis Flax Bollworm Moth Coptotriche aenea Blackberry Leafminer Argyresthia canadensis Apyrrothrix araxes Dull Firetip Phocides pigmalion Mangrove Skipper Phocides belus Belus Skipper Phocides palemon Guava Skipper Phocides urania Urania skipper Proteides mercurius Mercurial Skipper Epargyreus zestos Zestos Skipper Epargyreus clarus Silver-spotted Skipper Epargyreus spanna Hispaniolan Silverdrop Epargyreus exadeus Broken Silverdrop Polygonus leo Hammock Skipper Polygonus savigny Manuel's Skipper Chioides albofasciatus White-striped Longtail Chioides zilpa Zilpa Longtail Chioides ixion Hispaniolan Longtail Aguna asander Gold-spotted Aguna Aguna claxon Emerald Aguna Aguna metophis Tailed Aguna Typhedanus undulatus Mottled Longtail Typhedanus ampyx Gold-tufted Skipper Polythrix octomaculata Eight-spotted Longtail Polythrix mexicanus Mexican Longtail Polythrix asine Asine Longtail Polythrix caunus (Herrich-Schäffer, 1869) Zestusa dorus Short-tailed Skipper Codatractus carlos Carlos' Mottled-Skipper Codatractus alcaeus White-crescent Longtail Codatractus yucatanus Yucatan Mottled-Skipper Codatractus arizonensis Arizona Skipper Codatractus valeriana Valeriana Skipper Urbanus proteus Long-tailed Skipper Urbanus viterboana Bluish Longtail Urbanus belli Double-striped Longtail Urbanus pronus Pronus Longtail Urbanus esmeraldus Esmeralda Longtail Urbanus evona Turquoise Longtail Urbanus dorantes Dorantes Longtail Urbanus teleus Teleus Longtail Urbanus tanna Tanna Longtail Urbanus simplicius Plain Longtail Urbanus procne Brown Longtail -

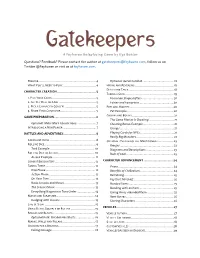

A Feyhaven Roleplaying Game by Ilya Bossov Questions?

Gatekeepers A Feyhaven Roleplaying Game by Ilya Bossov Questions? Feedback? Please contact the author at [email protected], follow us on Twitter @Feyhaven or visit us at feyhaven.com. PREMISE ...................................................................... 4 Optional: Aerial Combat ...................................... 18 WHAT YOU’LL NEED TO PLAY ......................................... 4 HIDING AND REVEALING ............................................... 18 DEATH AND TAXES ...................................................... 18 CHARACTER CREATION ............................................... 5 TAKING A GEAS ........................................................... 19 1. PICK YOUR CARDS ..................................................... 5 Fomorian Shapeshifters ...................................... 20 2. GET FEY DUST OR LOOT ............................................. 5 Fairies and Fomorians ......................................... 20 3. PICK A CHARACTER CONCEPT ...................................... 5 PETS AND MOUNTS ..................................................... 20 4. NAME YOUR CHARACTER ........................................... 5 Pet Example ........................................................ 20 GROUPS AND BOSSES .................................................. 21 GAME PREPARATION ................................................... 6 The Game Master Is Cheating! .............................. 21 Optional: Make More Connections........................ 7 Cheating Bonus Example ..................................... -

National Basketball Association

Appendix 2 to Sports Facility Reports, Volume 5, Number 2 ( Copyright 2005, National Sports Law Institute of Marquette University Law School) NATIONAL BASKETBALL ASSOCIATION Note: Information compiled from Forbes Magazine (franchise values), Lexis.com, Sports Business Journal, and other sources published on or before January12, 2005. Team Principal Owner Recent Purchase Current Value ($/Mil) Price ($/Mil) (Percent Increase/Decrease From Last Year) Atlanta Hawks Atlanta Spirit, LLC $250 (2004) $232 (+15%) includes Atlanta Hawks, Atlanta Thrashers (NHL), and operating rights in Philips Arena Arena ETA COST % FACILITY FINANCING (millions) Publicly Financed Philips Arena 1999 $213.5 91% The facility was financed through $149.5 M in taxable revenue bonds that will be paid back through stadium revenues. A new 3% car rental tax pays for $62 M of the public infrastructure costs and Time Warner contributed $20 M for the remaining infrastructure costs. UPDATE The purchase of the Hawks, Atlanta Thrashers (NHL) franchise, and operating rights in Philips Arena to the Atlanta Spirit, Inc. was finalized in March 2004. A recently reported investor with a 1% share in the franchise is Atlanta Hawks legend Dominique Wilkins. NAMING RIGHTS Philips Electronics is paying $185 million over 20 years for the naming rights that expire in 2019. Team Principal Owner Recent Purchase Current Value ($/Mil) Price ($/Mil) (Percent Increase/Decrease From Last Year) Boston Celtics Boston Basketball $360 (2002) $290 (+6%) Partners LP, a group made up of Wycliffe Grousbeck, H. Irving Grousbeck and Stephen Pagliuca. Arena ETA COST % FACILITY FINANCING (millions) Publicly Financed FleetCenter 1995 $160 0% Privately financed and owned by the NHL’s Bruins. -

Weekend Glance

Thursday, Nov. 30, 2017 Vol. 16 No. 34 SPORTS NEWS OBITUARIES ENTERTAINMENT Vikings advance Downey crime Robert Golay Netflix releases to title game report passes away for December SEE PAGE 3 SEE PAGE 4 SEE PAGE 5 SEE PAGE 9 Downey City Council chooses Sean Ashton restaurant to be next mayor grades Cafe N Stuff DECEMBER 1 9306 Firestone Blvd. CITY COUNCIL: Council members Date Inspected: 11/27/17 Long Beach City College avoid controversy by choosing Sean Friday 73˚ Grade: A Weekend dance concert Ashton as Downey’s next mayor. at a DATE: Friday, Dec. 1 Ichiban Sushi Glance By Alex Dominguez TIME: 7 pm 11020 New St. Staff Writer Saturday 74˚⁰ LOCATION: Downey Theatre Date Inspected: 11/15/17 Friday 68 Grade: A DECEMBER 2 DOWNEY – The Downey City Council unanimously voted current Family bicycle ride hosted by Jamba Juice Mayor Pro Tem Sean Ashton and Sunday 70˚ Downey Bicycle Coalition 12020 Lakewood Blvd. 70⁰ Councilman Rick Rodriguez as the Date Inspected: 11/15/17 Saturday DATE: Saturday, Dec. 2 Mayor and Mayor Pro Tem for Grade: A TIME: 7:45 am 2018, respectively, at Tuesday’s City Council meeting. LOCATION: Furman Park Mimi’s Donuts Downey traditionally rotates 10303 Lakewood Blvd. THINGS TO DO Mariachi Divas in concert Mayoral and Pro Tem duties Date Inspected: 11/16/17 DATE: Saturday, Dec. 2 annually, with council voting on Sean Ashton will be sworn-in as Downey’s next mayor Dec. 12. Grade: A TIME: 8 pm who will take the positions at the LOCATION: Downey Theatre end of each year. -

Themed Weeks Help Bring Awareness to Religion, Health and Human Rights

Today: Few Showers THE TUFTS High 42 Low 37 Tufts’ Student Tomorrow: Newspaper Showers Since 1980 High 44 Low 39 VOLUME LIII, NUMBER 51 DAILY WEDNESDAY, APRIL 18, 2007 Themed weeks help bring awareness Three speakers offer insights to religion, health and human rights on minor league baseball BY EVANS CLINCHY a brief speech about the grow- Daily Editorial Board ing popularity of the minor league game, a trend that the Three members of the Tufts rest of the speakers returned to community — Experimental throughout the night. College lecturer Andy Andres, “When you think about and alumni Ted Tye (A ’79) the number of people going and Tony Massarotti (LA ’89) to minor league games, it’s — visited the Tufts campus last more than the NFL and NHL night for a panel discussion on combined,” said Tye, whose minor league baseball. Tornadoes are expecting over The Ex College-sponsored one million fans in 2007. “That’s event, entitled “The Minor a stunning figure to me.” League Revival: Baseball, Tye discussed in detail the Entrepreneurship and process of creating an inde- Community,” was held in pendent minor league team. Barnum Hall before a small The Tornadoes originated in group of students and profes- 2005 after team organizers sors. Well-known baseball stat- oversaw the construction of a istician and Boston Red Sox 3,000-seat stadium in just nine consultant Bill James was also weeks, hired former Red Sox in attendance. players Rich Gedman and Bob Tye, who is the co-owner of Ojeda to run the player devel- the independent minor league opment department, and went team the Worcester Tornadoes, about building a 22-man ros- spoke about the management ter. -

Weekend Glance

Friday, Dec. 1, 2017 Vol. 11 No. 43 12040 Foster Road, Norwalk, CA 90650 Norwalk Norwalk City Council votes restaurant to give themselves grades Donut King 12000 Rosecrans Ave. NOVEMBER 30 12 more months in office Date Inspected: 11/17/17 FridayWeekend74˚ Neighborhood Watch meeting Grade: B CITY COUNCIL: Council members at a DATE: Thursday, Nov. 30 Glance choose to extend elections one year Buy Low Market TIME: 6:30 pm under legislation signed by Gov. Jerry Saturday 75˚⁰ LOCATION: Paddison Elementary 10951 Rosecrans Ave. 68 Brown. Date Inspected: 11/13/17 Friday DECEMBER 2 Grade: B By Raul Samaniego SnowFest and Christmas Tree Contributor Wienerschnitzel Sunday 71˚70⁰ Lighting 11660 Imperial Hwy. Saturday DATE: Saturday, Dec. 2 NORWALK – The Norwalk City Date Inspected: 11/15/17 TIME: 12-8 pm Council voted 5-0 on November Grade: A 21, to approve Ordinance 17-1698 LOCATION: City Hall lawn which called for the changing of Waba Grill Holiday Sonata Election Dates to comply with 11005 Firestone Blvd. California Senate Bill 415. DATE: Saturday, Dec. 2 Date Inspected: 11/16/17 TIME: 4-9 pm For Norwalk residents, it means Grade: A that with the approval of the Norwalk’s next election will be in 2020. Photo courtesy city of LOCATION: Uptown Whittier ordinance, “all five council members Norwalk Ana’s Bionicos have added another 12 months to 11005 Firestone Blvd. DECEMBER 5 their terms,” according to City Clerk numbered years to even, it could California’s history. Date Inspected: 11/16/17 Theresa Devoy increase the voter turnout for those City Council meeting This transition was mandated Grade: A elections. -

Moth Tails Divert Bat Attack: Evolution of Acoustic Deflection

Moth tails divert bat attack: Evolution of acoustic deflection Jesse R. Barbera,1, Brian C. Leavella, Adam L. Keenera, Jesse W. Breinholtb, Brad A. Chadwellc, Christopher J. W. McClurea,d, Geena M. Hillb, and Akito Y. Kawaharab,1 aDepartment of Biological Sciences, Boise State University, Boise, ID 83725; bFlorida Museum of Natural History, McGuire Center for Lepidoptera and Biodiversity, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL 32611; cDepartment of Anatomy and Neurobiology, Northeast Ohio Medical University, Rootstown, OH 44272; and dPeregrine Fund, Boise, ID 83709 Edited by May R. Berenbaum, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL, and approved January 28, 2015 (received for review November 15, 2014) Adaptations to divert the attacks of visually guided predators the individuals that were tested. Interactions took place under have evolved repeatedly in animals. Using high-speed infrared darkness in a sound-attenuated flight room. We recorded each videography, we show that luna moths (Actias luna) generate an engagement with infrared-sensitive high-speed cameras and ul- acoustic diversion with spinning hindwing tails to deflect echolo- trasonic microphones. To constrain the moths’ flight to a ∼1m2 cating bat attacks away from their body and toward these non- area surveyed by the high-speed cameras, we tethered luna moths essential appendages. We pit luna moths against big brown bats from the ceiling with a monofilament line. (Eptesicus fuscus) and demonstrate a survival advantage of ∼47% for moths with tails versus those that had their tails removed. The Results and Discussion benefit of hindwing tails is equivalent to the advantage conferred Bats captured 34.5% (number of moths presented; n = 87) of to moths by bat-detecting ears. -

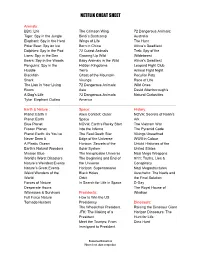

Netflix Cheat Sheet

NETFLIX CHEAT SHEET Animals: BBC: Life The Crimson Wing 72 Dangerous Animals: Tiger: Spy in the Jungle Bindi’s Bootcamp Australia Elephant: Spy in the Herd Wings of Life The Hunt Polar Bear: Spy on Ice Born in China Africa’s Deadliest Dolphins: Spy in the Pod 72 Cutest Animals Trek: Spy of the Lions: Spy in the Den Growing Up Wild Wildebeest Bears: Spy in the Woods Baby Animals in the Wild Africa’s Deadliest Penguins: Spy in the Hidden Kingdoms Leopard Fight Club Huddle Terra Animal Fight Night Blackfish Ghost of the Mountain Peculiar Pets Shark Virunga Race of LIfe The Lion in Your Living 72 Dangerous Animals: Wild Ones Room Asia David Attenborough’s A Dog’s Life 72 Dangerous Animals: Natural Curiosities Tyke: Elephant Outlaw America Earth & Nature : Space: History: Planet Earth II Alien Contact: Outer NOVA: Secrets of Noah’s Planet Earth Space Ark Blue Planet NOVA: Earth’s Rocky Start The Vietnam War Frozen Planet Into the Inferno The Pyramid Code Planet Earth: As You’ve The Real Death Star Vikings Unearthed Never Seen It Edge of the Universe WWII in Colour A Plastic Ocean Horizon: Secrets of the Untold Histories of the Earth’s Natural Wonders Solar System United States Mission Blue The Inexplicable Universe Nazi Mega Weapons World’s Worst Disasters The Beginning and End of 9/11: Truths, Lies & Nature’s Weirdest Events the Universe Conspiracy Nature’s Great Events Horizon: Supermassive Nazi Megastructures Weird Wonders of the Black Holes Auschwitz: The Nazis and World Orbit the Final Solution Forces of Nature In Search for Life in Space D-Day Desperate Hours: The Royal House of Witnesses & Survivors Presidents: Windsor Full Force Nature How to Win the US Tornado Hunters Presidency Dinosaurs: The Wheelchair President Raising the Dinosaur Giant JFK: The Making of a Horizon Dinosaurs: The President Hunt for Life Meet the Trumps: From Dino Hunt Immigrant to President HomeschoolHideout.com Please do not share or reproduce. -

Wildlife in Your Young Forest.Pdf

WILDLIFE IN YOUR Young Forest 1 More Wildlife in Your Woods CREATE YOUNG FOREST AND ENJOY THE WILDLIFE IT ATTRACTS WHEN TO EXPECT DIFFERENT ANIMALS his guide presents some of the wildlife you may used to describe this dense, food-rich habitat are thickets, T see using your young forest as it grows following a shrublands, and early successional habitat. timber harvest or other management practice. As development has covered many acres, and as young The following lists focus on areas inhabited by the woodlands have matured to become older forest, the New England cottontail (Sylvilagus transitionalis), a rare amount of young forest available to wildlife has dwindled. native rabbit that lives in parts of New York east of the Having diverse wildlife requires having diverse habitats on Hudson River, and in parts of Connecticut, Rhode Island, the land, including some young forest. Massachusetts, southern New Hampshire, and southern Maine. In this region, conservationists and landowners In nature, young forest is created by floods, wildfires, storms, are carrying out projects to create the young forest and and beavers’ dam-building and feeding. To protect lives and shrubland that New England cottontails need to survive. property, we suppress floods, fires, and beaver activities. Such projects also help many other kinds of wildlife that Fortunately, we can use habitat management practices, use the same habitat. such as timber harvests, to mimic natural disturbance events and grow young forest in places where it will do the most Young forest provides abundant food and cover for insects, good. These habitat projects boost the amount of food reptiles, amphibians, birds, and mammals.