Here Is a Printable

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Garage Zine Scionav.Com Vol. 3 Cover Photography: Clayton Hauck

GARAGE ZINE SCIONAV.COM VOL. 3 COVER PHOTOGRAPHY: CLAYTON HAUCK STAFF Scion Project Manager: Jeri Yoshizu, Sciontist Editor: Eric Ducker Creative Direction: Scion Art Director: malbon Production Director: Anton Schlesinger Contributing Editor: David Bevan Assistant Editor: Maud Deitch Graphic Designers: Nicholas Acemoglu, Cameron Charles, Kate Merritt, Gabriella Spartos Sheriff: Stephen Gisondi CONTRIBUTORS Writer: Jeremy CARGILL Photographers: Derek Beals, William Hacker, Jeremy M. Lang, Bryan Sheffield, REBECCA SMEYNE CONTACT For additional information on Scion, email, write or call. Scion Customer Experience 19001 S. Western Avenue Company references, advertisements and/ Mail Stop WC12 or websites listed in this publication are Torrance, CA 90501 not affiliated with Scion, unless otherwise Phone: 866.70.SCION noted through disclosure. Scion does not Fax: 310.381.5932 warrant these companies and is not liable for Email: Email us through the contact page their performances or the content on their located on scion.com advertisements and/or websites. Hours: M-F, 6am-5pm PST Online Chat: M-F, 6am-6pm PST © 2011 Scion, a marque of Toyota Motor Sales U.S.A., Inc. All rights reserved. Scion GARAGE zine is published by malbon Scion and the Scion logo are trademarks of For more information about MALBON, contact Toyota Motor Corporation. [email protected] 00430-ZIN03-GR SCION A/V SCHEDULE JUNE Scion Garage 7”: Cola Freaks/Digital Leather (June 7) Scion Presents: Black Lips North American Tour The Casbah in San Diego, CA (June 9) Velvet Jones -

Produced Byray Manzarek

PRODUCED BY RAY MANZAREK Originally released April 1980 Originally released May 1981 Originally released July 1982 Originally released September 1983 Frank Gargani Debbie Leavitt Power... Passion... Poetry! Attack the world. Let’s do some damage. What a band. Four monsters of skin. My favorite rockers of the then time. John Doe - Mr. Handsome - of the deep rich voice, the hard, strong jaw, the angular bass stance and the hot/cool lyrics. Their harmonies - some would say Schoenberg - his partner Exene, of the wailing scream in the night, the clear eyed pinning of American failings, the fine words of Diana Bonebrake love and booze and madness in the midnight dawn of Los Angeles. “Johny Hit and Run Paulene...” and he’s got a sterilized hypo filled with a sex-machine drug, and he only has 24 hours to shoot all Paulenes between the legs. So get busy, boy. And he does. Listen to those words! That naughty, naughty Johny. I love ‘em. And Exene’s “The World’s a Mess, it’s in My Kiss.” I just love that crazy combination: World - Mess - Kiss. And Billy Zoom on guitar, or is that at least 3 or 4 guitars. How does he do it? It’s so massive, so sharp, so bright, so fucking LOUD!!! And he is so silver smooth and cool. Effortless fingering, impeccable on the frets. Doesn’t he ever make a mistake? Is he a flesh and blood Valhalla guitar god? Yeahhh! And who is that madman beating the living shit out those drums? Ladies and Gentleman... D. -

Read Razorcake Issue #27 As A

t’s never been easy. On average, I put sixty to seventy hours a Yesterday, some of us had helped our friend Chris move, and before we week into Razorcake. Basically, our crew does something that’s moved his stereo, we played the Rhythm Chicken’s new 7”. In the paus- IInot supposed to happen. Our budget is tiny. We operate out of a es between furious Chicken overtures, a guy yelled, “Hooray!” We had small apartment with half of the front room and a bedroom converted adopted our battle call. into a full-time office. We all work our asses off. In the past ten years, That evening, a couple bottles of whiskey later, after great sets by I’ve learned how to fix computers, how to set up networks, how to trou- Giant Haystacks and the Abi Yoyos, after one of our crew projectile bleshoot software. Not because I want to, but because we don’t have the vomited with deft precision and another crewmember suffered a poten- money to hire anybody to do it for us. The stinky underbelly of DIY is tially broken collarbone, This Is My Fist! took to the six-inch stage at finding out that you’ve got to master mundane and difficult things when The Poison Apple in L.A. We yelled and danced so much that stiff peo- you least want to. ple with sourpusses on their faces slunk to the back. We incited under- Co-founder Sean Carswell and I went on a weeklong tour with our aged hipster dancing. -

Bad Rhetoric: Towards a Punk Rock Pedagogy Michael Utley Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 8-2012 Bad Rhetoric: Towards A Punk Rock Pedagogy Michael Utley Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Part of the Rhetoric and Composition Commons Recommended Citation Utley, Michael, "Bad Rhetoric: Towards A Punk Rock Pedagogy" (2012). All Theses. 1465. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/1465 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BAD RHETORIC: TOWARDS A PUNK ROCK PEDAGOGY A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Professional Communication by Michael M. Utley August 2012 Accepted by: Dr. Jan Rune Holmevik, Committee Chair Dr. Cynthia Haynes Dr. Scot Barnett TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Introduction ..........................................................................................................................4 Theory ................................................................................................................................32 The Bad Brains: Rhetoric, Rage & Rastafarianism in Early 1980s Hardcore Punk ..........67 Rise Above: Black Flag and the Foundation of Punk Rock’s DIY Ethos .........................93 Conclusion .......................................................................................................................109 -

Girls Like Us: Linder

Linder Sterling is a British These include her 13-hour artist and performer whose NICOLE EMMENEGGER improvised dance perfor- career spans the 1970s WORDS mance piece Darktown Cake- B Manchester punk scene to Y walk and her most recent her current collaborations work, The Ultimate Form, a with Tate St. Ives and The 'performance ballet' inspired Hepworth Centre in north- at the photographed by Barbara Hepworth, fea- west England. turing dancers from North- PORTRAITS PORTRAITS ern Ballet and costumes by She has worked in a variety B arbara Pam Hogg. of mediums – from music H B Y DEVIN (as singer/songwriter/gui- Ives St. Tate Museum in epworth We met at the The Barbican B tarist for post-punk band LAIR Centre in London on a crisp Ludus) and collage (using March morning, just days a steady scalpel to splice after the opening of her first pornographic images into big retrospective at Le Musée feminist statements), to her d’Art Moderne in Paris. current durational works. Linder 18 19 Nicole Emmenegger: First off, thank you for send- Yes, I used to have this fascination for the mid-fifties. People ing through the preparatory text about you and your I know at every age seem to have this fascination about the work. It ended up being ten pages in 10-point font! culture that you were born into, climbed into. It’s your own personal etymology and you have to go back and work it Linder: How strange, I don’t even enjoy writing! out. It’s good detective work. It makes sense and how lucky for you that 1976 was such a great year. -

Victorgories Packet Packet by Victor Pavao

Victorgories Packet Packet by Victor Pavao 1. In this symphony’s final movement, the horns introduce a disjunct secondary theme beginning “dotted half C, quarter note low G, dotted half high E.” Violins and cellos play thirty-second notes in the A-flat minor, third variation in this symphony’s second movement. Leonard Bernstein’s debut lecture on the CBS program (*) Omnibus was an analysis of this symphony. This symphony’s first movement features an oboe cadenza near the recapitulation. This symphony’s third movement continues into the fourth without pause, and ends with a note-for-note copy of the overture from Cherubini’s Eliza, which includes repeated C major chords. For 10 points, name this symphony whose first movement opens with the “G G G long Eb” fate motif. ANSWER: Ludwig van Beethoven, Symphony No. 5 in C Minor (prompt on “fate”) 2. A character who stays at this location repeatedly mentions her “cup of stars” after hearing a young girl demand one in a country restaurant. Two sisters who lived at this location fought bitterly over some family heirlooms, an argument that resulted in a companion’s suicide. While staying in this location, a character wakes up in the middle of the night to climb a deteriorated iron stairway. Arthur uses a device called a planchette in this place, which was once owned by Hugh (*) Crain. Theodora finds her room and clothes splashed in blood in this building, which is also visited by guests like Luke Sanderson and Eleanor Vance, who were invited to stay by Dr. -

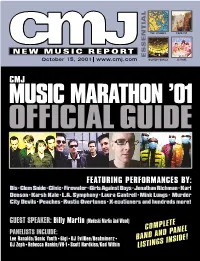

Complete Band and Panel Listings Inside!

THE STROKES FOUR TET NEW MUSIC REPORT ESSENTIAL October 15, 2001 www.cmj.com DILATED PEOPLES LE TIGRE CMJ MUSIC MARATHON ’01 OFFICIALGUIDE FEATURING PERFORMANCES BY: Bis•Clem Snide•Clinic•Firewater•Girls Against Boys•Jonathan Richman•Karl Denson•Karsh Kale•L.A. Symphony•Laura Cantrell•Mink Lungs• Murder City Devils•Peaches•Rustic Overtones•X-ecutioners and hundreds more! GUEST SPEAKER: Billy Martin (Medeski Martin And Wood) COMPLETE D PANEL PANELISTS INCLUDE: BAND AN Lee Ranaldo/Sonic Youth•Gigi•DJ EvilDee/Beatminerz• GS INSIDE! DJ Zeph•Rebecca Rankin/VH-1•Scott Hardkiss/God Within LISTIN ININ STORESSTORES TUESDAY,TUESDAY, SEPTEMBERSEPTEMBER 4.4. SYSTEM OF A DOWN AND SLIPKNOT CO-HEADLINING “THE PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE TOUR” BEGINNING SEPTEMBER 14, 2001 SEE WEBSITE FOR DETAILS CONTACT: STEVE THEO COLUMBIA RECORDS 212-833-7329 [email protected] PRODUCED BY RICK RUBIN AND DARON MALAKIAN CO-PRODUCED BY SERJ TANKIAN MANAGEMENT: VELVET HAMMER MANAGEMENT, DAVID BENVENISTE "COLUMBIA" AND W REG. U.S. PAT. & TM. OFF. MARCA REGISTRADA./Ꭿ 2001 SONY MUSIC ENTERTAINMENT INC./ Ꭿ 2001 THE AMERICAN RECORDING COMPANY, LLC. WWW.SYSTEMOFADOWN.COM 10/15/2001 Issue 735 • Vol 69 • No 5 CMJ MUSIC MARATHON 2001 39 Festival Guide Thousands of music professionals, artists and fans converge on New York City every year for CMJ Music Marathon to celebrate today's music and chart its future. In addition to keynote speaker Billy Martin and an exhibition area with a live performance stage, the event features dozens of panels covering topics affecting all corners of the music industry. Here’s our complete guide to all the convention’s featured events, including College Day, listings of panels by 24 topic, day and nighttime performances, guest speakers, exhibitors, Filmfest screenings, hotel and subway maps, venue listings, band descriptions — everything you need to make the most of your time in the Big Apple. -

Laura Harker & Paul Sullivan on Nick Cave and the 80S East

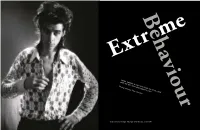

Behaviour 11 Extr me LaurA HArKer & PAul SullIvAn On Nick CAve AnD THe 80S East KreuzBerg SCene Photography by Peter gruchot 10 ecords), 24 April 1986 Studio session for the single ‘The Singer’ (Mute r Cutting a discreet diagonal between Kottbusser Tor and Oranienplatz, Dresdener Straße is one of the streets that provides blissful respite from east Kreuzberg’s constant hustle and bustle. Here, the noise of the traffic recedes and the street’s charms surge subtly into focus: fashion boutiques and indie cafés tucked into the ground floors of 19th Century Altbauten, the elegantly run-down Kino Babylon and the dark and seductive cocktail bar Würgeengel, the “exterminating angel”, a name borrowed from a surrealist film by luis Buñuel. It all looked very different in the 80s of course, when the Berlin Wall stood just under a kilometre away and the façades of these houses – now expensively renovated and worth a pretty penny – were still pockmarked by World War Two bulletholes. Mostly devoid of baths, the interiors heated by coal, their inhabitants – mostly Turkish immigrants – shivered and shuffled their way through the Berlin winter. 12 13 It was during this pre-Wende milieu that a tall, skinny and largely unknown Australian musician named Nicholas Edward Cave moved into no. 11. Aside from brief spells in apartments on naumannstraße (Schöneberg), yorckstraße, and nearby Oranienstraße, Cave spent the bulk of his seven on-and-off years in Berlin living in a tiny apartment alongside filmmaker and musician Christoph Dreher, founder of local outfit Die Haut. It was in this house that Cave wrote the lyrics and music for several Birthday Party and Bad Seeds albums, penned his debut novel (And The Ass Saw The Angel) and wielded a sizeable influence over Kreuzberg’s burgeoning post-punk scene. -

CHRISTIAN DEATH Street Date: Only Theatre of Pain, LP AVAILABLE NOW!

CHRISTIAN DEATH Street Date: Only Theatre of Pain, LP AVAILABLE NOW! INFORMATION: Artist Hometown: Los Angeles Key Markets: Los Angeles, Orange County CA, New York, Europe (France, Germany, Belgium in particular), Japan, Mexico For Fans of: ROZZ WILLIAMS, 45 GRAVE, BAUHAUS, XMAL DEUTSCHLAND, SIOUXSIE AND THE BANSHEES, DELERIUM, SWANS The founding fathers of American goth-rock, CHRISTIAN DEATH released their debut, Only Theatre of Pain, on Frontier Records in March 1982, and that landmark album has had an enormous influence on goth, death-rock, ARTIST: CHRISTIAN DEATH dark-wave, metal and even industrial music scenes all over the world, TITLE: Only Theatre of Pain shaping the approach of more bands than can be counted. Led by vocalist LABEL: Frontier Records and founder Rozz Williams, the CHRISTIAN DEATH of Only Theatre of Pain CAT#: 31007-1-W included guitarist Rikk Agnew, fresh out of THE ADOLESCENTS, bassist FORMAT: LP James McGearty, drummer George Belanger and backing vocals from GENRE: Gothic Rock, Goth, Superheroines leader (and Rozz’s future wife), Eva O as well as performance Death Rock, Punk artist Ron Athey. It was this line-up, with its dirgy, effects-laden guitar riffs BOX LOT: 50 and ambient horror-soundtrack synths, that crystalized the ominous post- SRLP: $14.98 punk sound that has established this album as the ultimate archetype of goth UPC: 018663100715 EXPORT: NO RESTRICTIONS sensibility. Genre touchstones include “Romeo’s Distress,” “Spiritual Cramp” and “Mysterium Iniquitatis.” Marketing Points: Tracklist: • This is a one-time only MISS-PRESS of the newly remastered version of 1. Cavity - First Communion the OTOP but with the previous edition’s black and gold LP jacket 2. -

NICK CAVE &The Bad Seeds

DAustrAlisk A NyA ZeeläWNNdskA väNskApsföreNiNgeN www.AustrAlieN-Ny AZeelANd.se UNDER NR 1 / 2013 NICK CAVE & THE BAD FISKEÄVENTYR SEEDS i Auckland intervju + recension Husbils- SEMESTER på Nya Zeeland THE GRAND B.Y.O, Barbie & Beetroot? CIRCLE Nyheter & medlemsförmåner Tasmanien runt The Swan Bell Tower / Whitsundays Hells Gate i Rotorua / Stewart Island VÄNSKAPSFÖRENINGENS NYA HEMSIDA På hemsidan hittar du senaste nytt om evenemang, nyheter, medlemsförmåner och tips. Du kan läsa artiklar, reseskildringar och få information om working holiday, visum mm. Besök WWW.AUSTRalien-nYAZEELAND.SE I AUSTRALISKA NYA ZEELÄNDSKA VÄNSKAPSFÖRENINGEN Medlemsavgift 200:- kalenderår. Förutom vår medlemstidning erhåller du en mängd rabatter hos företag och föreningar som vi samarbetar med. Att bli medlem utvecklar och lönar sig! Inbetalning till PlusGiro konto 54 81 31-2. Uppge Bli namn, medlem ev. medlemsnummer och e-postadress. 2 Det känns The Grand Circle - Tasmanian runt 5 & att få skriva årets första ledare i detta nr 1 år 2013. Nytt år och ny layout på Down Under, dessutom en massa spän- nande aktiviteter på gång i kalendern.inspirerande Jag vet att många av er un- der våra kallaste månader, november till februari varit på besök i våra länderfantastiskt Australien och kul Nya Zeeland. Jag tycker det är lika spännande varje gång att få höra om vad ni upplevt och varit med om. Skriv gärna och berätta om era resor till oss på Down Under. Den 10 februari hade vi årsmöte i Lund, ett möte som även inne- höll en spännande föreläsning av vår ordförande Erwin Apitzsch. Föreningens samarbete med Studiefrämjandet gjorde att vi kunde använda oss av deras lokaler, något vi är mycket tacksamma över. -

Taj Mahal Andyt & Nick Nixon Nikki Hill Selwyn Birchwood

Taj Mahal Andy T & Nick Nixon Nikki Hill Selwyn Birchwood JOE BONAMASSA & DAVE & PHIL ALVIN NUMBER FIVE www.bluesmusicmagazine.com US $7.99 Canada $9.99 UK £6.99 Australia A$15.95 COVER PHOTOGRAPHY © ART TIPALDI NUMBER FIVE 6 KEB’ MO’ Keeping It Simple 5 RIFFS & GROOVES by Art Tipaldi From The Editor-In-Chief 24 DELTA JOURNEYS 11 TAJ MAHAL “Jukin’” American Maestro by Phil Reser 26 AROUND THE WORLD “ALife In The Music” 14 NIKKI HILL 28 Q&A with Joe Bonamassa A Knockout Performer 30 Q&A with Dave Alvin & Phil Alvin by Tom Hyslop 32 BLUES ALIVE! Sonny Landreth / Tommy Castro 17 ANDY T & NICK NIXON Dennis Gruenling with Doug Deming Unlikely Partners Thorbjørn Risager / Lazy Lester by Michael Kinsman 37 SAMPLER 5 20 SELWYN BIRCHWOOD 38 REVIEWS StuffOfGreatness New Releases / Novel Reads by Tim Parsons 64 IN THE NEWS ANDREA LUCERO courtesy of courtesy LUCERO ANDREA FIRE MEDIA SHORE © PHOTOGRAPHY PHONE TOLL-FREE 866-702-7778 E-MAIL [email protected] WEB bluesmusicmagazine.com PUBLISHER: MojoWax Media, Inc. “Leave your ego, play the music, PRESIDENT: Jack Sullivan love the people.” – Luther Allison EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Art Tipaldi CUSTOMER SERVICE: Kyle Morris Last May, I attended the Blues Music Awards for the twentieth time. I began attending the GRAPHIC DESIGN: Andrew Miller W.C.Handy Awards in 1994 and attended through 2003. I missed 2004 to celebrate my dad’s 80th birthday and have now attended 2005 through 2014. I’ve seen it grow from its CONTRIBUTING EDITORS David Barrett / Michael Cote / Thomas J. Cullen III days in the Orpheum Theater to its present location which turns the Convention Center Bill Dahl / Hal Horowitz / Tom Hyslop into a dazzling juke joint setting. -

Razorcake Issue

RIP THIS PAGE OUT Curious about how to realistically help Razorcake? If you wish to donate through the mail, please rip this page out and send it to: Razorcake/Gorsky Press, Inc. PO Box 42129 Los Angeles, CA 90042 Just NAME: turn ADDRESS: the EMAIL: page. DONATION AMOUNT: 5D]RUFDNH*RUVN\3UHVV,QFD&DOLIRUQLDQRWIRUSUR¿WFRUSRUDWLRQLVUHJLVWHUHG DVDFKDULWDEOHRUJDQL]DWLRQZLWKWKH6WDWHRI&DOLIRUQLD¶V6HFUHWDU\RI6WDWHDQGKDV EHHQJUDQWHGRI¿FLDOWD[H[HPSWVWDWXV VHFWLRQ F RIWKH,QWHUQDO5HYHQXH &RGH IURPWKH8QLWHG6WDWHV,562XUWD[,'QXPEHULV <RXUJLIWLVWD[GHGXFWLEOHWRWKHIXOOH[WHQWSURYLGHGE\ODZ SUBSCRIBE AND HELP KEEP RAZORCAKE IN BUSINESS Subscription rates for a one year, six-issue subscription: U.S. – bulk: $16.50 • U.S. – 1st class, in envelope: $22.50 Prisoners: $22.50 • Canada: $25.00 • Mexico: $33.00 Anywhere else: $50.00 (U.S. funds: checks, cash, or money order) We Do Our Part www.razorcake.org Name Email Address City State Zip U.S. subscribers (sorry world, int’l postage sucks) will receive either Grabass Charlestons, Dale and the Careeners CD (No Idea) or the Awesome Fest 666 Compilation (courtesy of Awesome Fest). Although it never hurts to circle one, we can’t promise what you’ll get. Return this with your payment to: Razorcake, PO Box 42129, LA, CA 90042 If you want your subscription to start with an issue other than #72, please indicate what number. TEN NEW REASONS TO DONATE TO RAZORCAKE VPDQ\RI\RXSUREDEO\DOUHDG\NQRZRazorcake ALVDERQDILGHQRQSURILWPXVLFPDJD]LQHGHGLFDWHG WRVXSSRUWLQJLQGHSHQGHQWPXVLFFXOWXUH$OOGRQDWLRQV The Donation Incentives are…