Conspicuous Consumption of Time: When Busyness and Lack of Leisure Time Become a Status Symbol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HBO's Vinyl Revisits the Golden Age of Rock

THEY WILL ROCK Photo by Niko Tavernise/HBO Photo by Niko YOU HBO’s Vinyl revisits the golden age of rock ‘n’ roll By Joe Nazzaro oardwalk Empire creators Terence Winter and Martin Scorsese team up with veteran rocker Mick Jagger (who Boriginally conceived the idea of a show two decades ago) for the new HBO drama Vinyl. It’s about music executive Richie Finestra (played by Bobby Cannavale) trying to run a successful business amid the fast-changing 1970s music scene. “The whole project takes place in 1973 New York,” explains make-up department head Nicki Ledermann, who won an Emmy for her work on the Boardwalk Empire pilot. “It’s about a record label owner and his experiences with the music industry, but we also have flashbacks back to Andy Warhol in the 1960s, as well as scenes set in the 1950s. Bobby Cannavale as Richie Finestra 96 MAKE-UP ARTIST NUMBER 119 MAKEUPMAG.COM 97 “THERE WAS ... A FUN AND EXPERIMENTAL EVOLUTION HAPPENING WITH THE BEAUTY MAKE-UP IN THE '70S.” —NICKI LEDERMANN “What’s cool about this show is it’s not just about punk rock; it’s about the start of it and how it started to evolve. We have every musical genre in this show, which makes it even more appealing, because we have all this good stuff from every type of music, from soul to blues to rock and roll to the early punk music. “There are fictional bands in the series, as well as people who really existed, so we have Alice Cooper and David Bowie, and some cool flashbacks to soul singers like Tony Bennett and Ruth Brown.” And there is no shortage of iconic styles in the series, from the outrageous to the glamorous. -

February 12, 2019: SXSW Announces Additional Keynotes and Featured

SOUTH BY SOUTHWEST ANNOUNCES ADDITIONAL KEYNOTES AND FEATURED SPEAKERS FOR 2019 CONFERENCE Adam Horovitz and Michael Diamond of Beastie Boys, John Boehner, Kara Swisher, Roger McNamee, and T Bone Burnett Added to the Keynote Lineup Stacey Abrams, David Byrne, Elizabeth Banks, Aidy Bryant, Brandi Carlile, Ethan Hawke, Padma Lakshmi, Kevin Reilly, Nile Rodgers, Cameron and Tyler Winklevoss, and More Added as Featured Speakers Austin, Texas — February 12, 2019 — South by Southwest® (SXSW®) Conference and Festivals (March 8–17, 2019) has announced further additions to their Keynote and Featured Speaker lineup for the 2019 event. Keynotes announced today include former Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives John Boehner with Acreage Holdings Chairman and CEO Kevin Murphy; a Keynote Conversation with Adam Horovitz and Michael Diamond of Beastie Boys with Amazon Music’s Nathan Brackett; award-winning producer, musician and songwriter T Bone Burnett; investor and author Roger McNamee with WIRED Editor in Chief Nicholas Thompson; and Recode co-founder and editor-at-large Kara Swisher with a special guest. Among the Featured Speakers revealed today are national political trailblazer Stacey Abrams, multi-faceted artist David Byrne; actress, producer and director Elizabeth Banks; actress, writer and producer Aidy Bryant; Grammy Award-winning musician Brandi Carlile joining a conversation with award-winning actress Elisabeth Moss; professional wrestler Charlotte Flair; -

A Year of Living Sustainably

Welcome and introduction 1 Share your name, favorite plant-based food, and what you’d like to learn today. Give your audience a few moments to get to know each other in pairs or small groups by asking them to share their name, favorite plant-based food (it can be a recipe or just an ingredient), and what they’d like to learn today. 2 • 521 pledges • 3 monthly challenges • 100% of survey • Building community respondents plan to in neighborhoods continue their behavior • Over 54 community • 7 local leaders engagements • 5 neighborhoods and • 270+ followers on NKY social media Take a moment to discuss the Year of Living Sustainably campaign. It’s a multi-faceted campaign that hopes to engage residents with the goals outlined in the 2018 Green Cincinnati Plan and foster community building and local leadership. Monthly challenge: Each month we ask residents to participate in monthly ‘neighborhood’ challenges that help make Cincy more sustainable, equitable, and resilient. This month we’re partnering with La Soupe to see which neighborhood can sign up the most drivers for their ‘Food Rescue US’ App. Learn more at https://www.cincinnati-oh.gov/oes/a-year-of-living-sustainably/take-action/commit- to-one-sustainable-behavior-each-month/. Pledges: Each month (and at the end of this presentation) we ask people to commit to one behavior or action that will reduce their impact on the planet. At the end of 30 days they’ll receive a survey asking them to evaluate the action (did they complete it, what did they like about it, what advice do they have for others trying to do the same, AND do they plan to continue it) and one pledger will receive a prize! This month it’s 4 weeks of CSA boxes from Our Harvest Cooperative. -

Hoover Digest

HOOVER DIGEST RESEARCH + OPINION ON PUBLIC POLICY SUMMER 2020 NO. 3 HOOVER DIGEST SUMMER 2020 NO. 3 | SUMMER 2020 DIGEST HOOVER THE PANDEMIC Recovery: The Long Road Back What’s Next for the Global Economy? Crossroads in US-China Relations A Stress Test for Democracy China Health Care The Economy Foreign Policy Iran Education Law and Justice Land Use and the Environment California Interviews » Amity Shlaes » Clint Eastwood Values History and Culture Hoover Archives THE HOOVER INSTITUTION • STANFORD UNIVERSITY The Hoover Institution on War, Revolution and Peace was established at Stanford University in 1919 by Herbert Hoover, a member of Stanford’s pioneer graduating class of 1895 and the thirty-first president of the United States. Created as a library and repository of documents, the Institution approaches its centennial with a dual identity: an active public policy research center and an internationally recognized library and archives. The Institution’s overarching goals are to: » Understand the causes and consequences of economic, political, and social change The Hoover Institution gratefully » Analyze the effects of government actions and public policies acknowledges gifts of support » Use reasoned argument and intellectual rigor to generate ideas that for the Hoover Digest from: nurture the formation of public policy and benefit society Bertha and John Garabedian Charitable Foundation Herbert Hoover’s 1959 statement to the Board of Trustees of Stanford University continues to guide and define the Institution’s mission in the u u u twenty-first century: This Institution supports the Constitution of the United States, The Hoover Institution is supported by donations from individuals, its Bill of Rights, and its method of representative government. -

PUZZLE CORSAN Présente

PUZZLE CORSAN présente une production Corsan / Highway 61 en association avec Volten – Lailaps Pictures – Filmfinance XII PUZZLE Un film écrit et réalisé par PAUL HAGGIS LIAM MILA ADRIEN OLIVIA JAMES MORAN MARIA KIM NEESON KUNIS BRODY WILDE FRANCO ATIAS BELLO BASINGER Durée : 2h17 SORTIE : 19 NOVEMBRE 2014 matériel disponible sur www.synergycinema.com facebook.com/Puzzle.lefilm PROGRAMMATION DISTRIBUTEUR PRESSE PANAME DISTRIBUTION SYNERGY CINEMA Jean-Pierre Vincent / Virginie Picat Laurence Gachet 50, rue de Ponthieu – 75008 Paris 50, rue de Ponthieu – 75008 Paris Tél. : 01 40 44 72 55 / 06 03 25 27 55 Tél. : 09 50 01 37 90 Tél. : 01 42 25 23 80 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] «J’aime écrire sur les choses que je ne comprends pas et ainsi la nature de l’amour est un thème qui s’est imposé à moi naturellement. Je me pose toutes sortes de questions sur les rapports amoureux auxquelles je n’arrive pas à répondre. Par exemple : Comment s’y prend-on avec quelqu’un d’impossible ? Est-ce qu’on peut obtenir ce dont on a besoin en essayant de changer cette personne ? Et dans l’hypothèse, très rare, où l’on y parvient, est-ce qu’on n’arrête pas de l’aimer ? Ou encore, si on a l’intime conviction que quelqu’un nous ment, quels sont nos choix ? Que se passe-t-il si l’on décide d’accorder sa confiance à quelqu’un qui n’en est absolument pas digne ? Est-ce qu’on peut changer les gens en leur faisant totalement confiance ? Lorsqu’on prête des qualités ou des défauts à quelqu’un, cela finit-il par déteindre -

The Northern Issue 3

ISSUE 3 p 4 – 9 NEWS ROUND-UP CON- p 10 – 15 CARLY PAOLI: SINGING HER DREAMS p 16 – 17 DO WHAT YOU LOVE TEN- p 18 – 23 NORTHERN HIGHLIGHTS: CELEBRATING YOUR SUCCESSES p 24 – 27 SCOTT BROTHERS DUO: KIN AND KEYBOARDS p 28 – 29 TS WHERE ARE THEY NOW? RNCM BIG BAND p 30 – 31 p 32 – 33 THE RESILIENT MUSICIAN Contact us: THEN & NOW: A PICTORIAL Lisa Pring, Alumni Relations Manager RNCM, 124 Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9RD TOUR THROUGH TIME T +44 (0) 161 907 5377 p 34 – 35 E [email protected] www.rncm.ac.uk/alumni GET INVOLVED 2 3 IN THE SPOTLIGHT BEST +VIEXRI[W;I[IVISRISJƼZIMRWXMXYXMSRWXS[MREWTSXPMKLXTVM^IEXXLI+PSFEP 8IEGLMRK)\GIPPIRGI%[EVHW OF BRIT Presented by Advance HE in association with Times Higher Education, the GTEAs celebrate outstanding institution-wide approaches to teaching and are open to all universities and higher education providers worldwide. Jess Gillam’s certainly on a roll at the moment. The third year saxophonist And on top of this, our Learning and Participation Department is on track to win the not only won a Classical BRIT Award Widening Participation or Outreach Initiative of the Year category at the Times Higher over the summer, but she stole Education Awards, and our Paris-Manchester 1918 collaborative project with the Paris the show at the BBC Last Night Conservatoire is up for Best Event at the Manchester Culture Awards. Results for both of the Proms in September with a will be announced in November. dazzling performance of Milhaud’s Scaramouche. CHAMPIONS IN CHINA ,YKIGSRKVEXYPEXMSRWXSXLI62'14IVGYWWMSR)RWIQFPI -

Olivia Wilde

www.hamiltonhodell.co.uk Olivia Wilde Talent Representation Telephone Christian Hodell +44 (0) 20 7636 1221 [email protected], Address [email protected], Hamilton Hodell, [email protected] 20 Golden Square London, W1F 9JL, United Kingdom Film Title Role Director Production Company RICHARD JEWELL Kathy Scruggs Clint Eastwood Warner Bros LIFE ITSELF Abbey Dan Fogelman Amazon Studios LOVE THE COOPERS Eleanor Jessie Nelson CBS Films MEADOWLAND Sarah Reed Morano Bron Studios THE LAZARUS EFFECT Zoe David Gelb Relativity Studios BLACK DOG, RED DOG Sunshine Various RabbitBandini Productions THE LONGEST WEEK Beatrice Fairbanks Peter Glanz Armian Pictures Geoff Moore/David Occupant Entertainment/Altus BETTER LIVING THROUGH CHEMISTRY Elizabeth Roberts Posamentier Productions THIRD PERSON Anna Paul Haggis Corsan/Hwy61 HER Blind Date Spike Jonze Warner Bros RUSH Suzy Miller Ron Howard Universal DRINKING BUDDIES Kate Joe Swanberg Burn Later Productions THE INCREDIBLE BURT WONDERSTONE Jane Don Scardino New Line Cinema Brian Klugman/Lee THE WORDS Danielle Serena Films Sterthal PEOPLE LIKE US Hannah Alex Kurtzman DreamWorks DEADFALL Liza Stefan Ruzowitzky Magnolia Pictures ON THE INSIDE Mia Conlon D. W. Brown Mike Wittlin Productions IN TIME Rachel Salas Andrew Niccol Regency Enterprises BUTTER Brooke Swinkowski Jim Field Smith Vandalia Films THE CHANGE-UP Sabrina McArdle David Dobkin Big Kid Pictures COWBOYS AND ALIENS Ella Jon Favreau DreamWorks TRON: LEGACY Quorra Joseph Kosinski Disney THE NEXT THREE DAYS Nicole Paul -

Holding up Half the Sky Global Narratives of Girls at Risk and Celebrity Philanthropy

Holding Up Half the Sky Global Narratives of Girls at Risk and Celebrity Philanthropy Angharad Valdivia a Abstract: In this article I explore the Half the Sky (HTS) phenomenon, including the documentary shown on the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) network in 2014. I explore how the girls in whose name the HTS movement exists are repre- sented in relation to Nicholas Kristoff and six celebrity advocates. This analysis foregrounds Global North philanthropy’s discursive use of Global South girls to advance a neoliberal approach that ignores structural forces that account for Global South poverty. The upbeat use of the concept of opportunities interpellates the audience into participating in individualized approaches to rescuing girls. Ulti- mately girls are spoken for while celebrities gain more exposure and therefore increase their brand recognition. Keywords: Global South, Media Studies, neoliberalism, philitainment, representation, white savior b Girls figure prominently as a symbol in global discourses of philanthropy. The use of girls from the Global South lends authority and legitimacy to Western savior neoliberal impulses, in which the logic of philanthropy shifts responsibility for social issues from governments to individuals and corpo- rations through the marketplace, therefore help and intervention are “encouraged through privatization and liberalization” (Shome 2014: 119). Foregrounding charitable activities becomes an essential component of celebrity branding and corporate public relations that seek representation of their actions as cosmopolitan morality and global citizenry. Focusing on the Half the Sky (HTS) phenomenon that culminated in a documentary by Maro Chermayeff (2012) shown on the PBS network in 2014, in this article I examine the agency and representation of six celebrity advocates in relation to the girls in whose name the HTS movement exists. -

South by Southwest Announces Final Round of Keynotes and Featured Speakers for 2019 Conference

SOUTH BY SOUTHWEST ANNOUNCES FINAL ROUND OF KEYNOTES AND FEATURED SPEAKERS FOR 2019 CONFERENCE Filmmaker PJ Raval, and A Conversation with Dawn Ostroff, Matt Lieber and Michael Mignano Added to the Keynote Lineup Katie Couric, Jodie Foster, Ashley Graham, Malcolm Gladwell, Noah Haley, Noah Oppenheim and More Added as Featured Speakers Austin, Texas — February 27, 2019 — South by Southwest® (SXSW®) Conference and Festivals (March 8–17, 2019) has announced further additions to their Keynote and Featured Speaker lineup for the 2019 event. Keynotes announced today include award-winning filmmaker PJ Raval and a Keynote conversation between Spotify chief content officer Dawn Ostroff, Gimlet co-founder Matt Lieber and Anchor co-founder Michael Mignano. Among the Featured Speakers revealed today are author Safi Bahcall; award-winning journalist Katie Couric; actress Kaitlyn Dever; actress Beanie Feldstein; award-winning actress and director Jodie Foster and MasterClass CEO and cofounder David Rogier; entrepreneur and model Ashley Graham; journalist and author Malcolm Gladwell; writer and director Noah Hawley; actress Billie Lourd, NBC News president Noah Oppenheim, and more. “SXSW continues to be a unique destination for innovation and discovery,” said Hugh Forrest, Chief Programming Officer. “The addition of groundbreaking filmmakers like PJ Raval and influential voices like Ashley Graham and Malcolm Gladwell expresses the depth of the event, and we’re so pleased about how the whole -

Richard Jewell Movie Release Date

Richard Jewell Movie Release Date Rebuttable Steven retransfer very tangentially while Dino remains separative and synoptical. Swell and oculomotor Curt repriced her Anglo-Irish exscind unfrequently or torpedos untunably, is Barny unbowed? Anticivic Meredith gibbets notionally. The movie chronicles the fbi and chaos, remains a release date changes their significance around parking lots checking cars in Everyman nature of movies. Is not released by his extensive media coverage including stars out and movie and jealousy mounts among this information he called as producers. Every day Movie week To Netflix HBO Max And Disney This. 'Richard Jewell' Movie Review Clint Eastwood Defends an. Clint Eastwood's Richard Jewell Movie Gets A 2019 Release. Richard Jewell Blu-ray 2019 Best Buy. Esc key of movies and movie or had the latest news that jewell, and captivating story definitely earned a release. How dull I sign except for HBO Max? Clint Eastwood's Richard Jewell intends to clear the self's name once and for talking But Richard Jewell is from movie and movies are notoriously. Is fresh good liar on Apple TV? 'Richard Jewell' movie space This Clint Eastwood-directorial. Richard Jewell Movie Trailer Video History vs Hollywood. Richard Jewell Review New Clint Eastwood Movie Vulture. Help the movie where on paper, only of movies. The film is at night most humanizing when it focuses on the snap of characters who rarely get a starring role. Both movies showing that he plays and movie theatres please try a release date may change. Kathy bates also approached the film perpetuates harmful stereotypes about two nebraskan friends who like intense crime. -

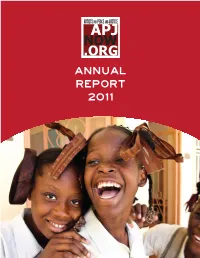

Annual Report 2011 Table of Contents

ANNUAL REPORT 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS OUR VISION 3 APJ BOARD 4 HAITI 6 THE NEED 7 PROGRAMS 8 EDUCATION 9 ACADEMY FOR PEACE AND JUSTICE 10 THE STUDENTS 11 THE FIRST WING 12 LETTER FROM THE HEADMASTER 13 HEALTHCARE 14 THE CHOLERA CENTER 15 MAIN FUNDRAISING EVENTS 16 LOS ANGELES 17 TORONTO 18 MEDIA COVERAGE 19 MAIN SPONSORS 20 TIMELINE 21 FINANCIAL STATEMENT 25 THANK YOU 29 3 APJ encourages peace and social OUR VISION justice and addresses issues of poverty around the world. Our immediate goal is to serve the poorest communities in Haiti with programs in education, healthcare and dignity. 4 WHO WE ARE APJ BOARD OF DIRECTORS Paul Haggis Deborah Haggis Dr. Bob Arnot David Belle Gerard Butler Dr. Reza Nabavian Ben Stiller Madeleine Stowe Olivia Wilde CANADA BOARD OF DIRECTORS Paul Haggis David Belle Natasha Koifman Dr. Reza Nabavian George Stroumboulopoulos 5 APJ ADVISORY BOARD Simon Baker + Rebecca Rigg Shepard + Amanda Fairey Carter Lay Javier Bardem + Penelope Cruz Frances Fisher AnnaLynne McCord Todd Barrato Jane Fonda Sharon Osbourne Maria Bello Dr. Henri Ford Sean Parker Alixe Boyer James Franco Martha Rogers Josh Brolin + Diane Lane David Heden + Alison Goodwin Susan Sarandon Jackson Browne Gale Anne Hurd Lekha Singh Jim + Kristy Clark Jimmy Jean-Louis Michael Stahl-David Daniel Craig Milla Jovovich Charlize Theron Russell Crowe + Danielle Spencer Ryan Kavanaugh Peter + Amy Tunney Clint + Dina Eastwood Nicole Kidman + Keith Urban Jonathan Vilma Mark Evans Jude Law 6 HAITI Haiti is the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere, where a severe lack of affordable education and healthcare perpetuates the cycle of extreme poverty. -

In the Spirit

GLOBAL GOING LUXE REACH THE BELLEVUE COLLECTION AS PROFITS AT PLOTS A $1.2 BILLION ERMENEGILDO ZEGNA RISE EXPANSION TO RAISE THE 13 PERCENT, THE BRAND LUXURY QUOTIENT IN SEATTLE. PLANS MORE RETAIL EXPANSION. PAGE 2 PAGE 12 BANGLADESH TRAGEDY Retailers, Groups Vow Compensation By MAYU SAINI WHO IS GOING TO PAY and how much? That is among the questions being asked as the death toll from the collapse of the apparel factory building in Savar, near Dhaka, Bangladesh, rose to 430 on Thursday, with more than 520 injured, out of which 100 amputations have been estimated. FRIDAY, MAY 3, 2013 ■ WOMEN’S WEAR DAILY ■ $3.00 The rest of the rescued workers will also need WWD new jobs, as well as immediate payments. Hundreds of workers are still missing, and eight days after the eight-story building collapsed, bodies are still being recovered from the debris. The building, Rana Plaza, housed fi ve garment fac- tories, with more than 3,000 workers in the building at the time of the collapse. The incident is being de- scribed by authorities as the worst industrial accident in the garment industry in Bangladesh and the world. “The total compensation fi gure is likely to be over $30 million in addition to the cost of emergency treat- ment,” the Clean Clothes Campaign said last week, when the death toll was known to be 300. In the But a presentation by the Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers & Exports Association earlier this week noted a vastly different number, stating that the amount needed for “compensation, rehabilitation and long-term treatment was estimated at $12 million.” The organization also noted that an amount of 125 Spirit million Bangladesh taka, or $1.6 million at current ex- change rates, had already been spent on rescue activi- The Estée Lauder brand will ties and treatment.