Literary Cultures in History Reconstructions from South Asia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mahabharata

^«/4 •m ^1 m^m^ The original of tiiis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924071123131 ) THE MAHABHARATA OF KlUSHNA-DWAIPAYANA VTASA TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH PROSE. Published and distributed, chiefly gratis, BY PROTSP CHANDRA EOY. BHISHMA PARVA. CALCUTTA i BHiRATA PRESS. No, 1, Raja Gooroo Dass' Stbeet, Beadon Square, 1887. ( The righi of trmsMm is resem^. NOTICE. Having completed the Udyoga Parva I enter the Bhishma. The preparations being completed, the battle must begin. But how dan- gerous is the prospect ahead ? How many of those that were counted on the eve of the terrible conflict lived to see the overthrow of the great Knru captain ? To a KsJtatriya warrior, however, the fiercest in- cidents of battle, instead of being appalling, served only as tests of bravery that opened Heaven's gates to him. It was this belief that supported the most insignificant of combatants fighting on foot when they rushed against Bhishma, presenting their breasts to the celestial weapons shot by him, like insects rushing on a blazing fire. I am not a Kshatriya. The prespect of battle, therefore, cannot be unappalling or welcome to me. On the other hand, I frankly own that it is appall- ing. If I receive support, that support may encourage me. I am no Garuda that I would spurn the strength of number* when battling against difficulties. I am no Arjuna conscious of superhuman energy and aided by Kecava himself so that I may eHcounter any odds. -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION ’ P”(Bha.t.tikāvya) is one of the boldest “B experiments in classical literature. In the formal genre of “great poem” (mahākāvya) it incorprates two of the most powerful Sanskrit traditions, the “Ramáyana” and Pánini’s grammar, and several other minor themes. In this one rich mix of science and art, Bhatti created both a po- etic retelling of the adventures of Rama and a compendium of examples of grammar, metrics, the Prakrit language and rhetoric. As literature, his composition stands comparison with the best of Sanskrit poetry, in particular cantos , and . “Bhatti’s Poem” provides a comprehensive exem- plification of Sanskrit grammar in use and a good introduc- tion to the science (śāstra) of poetics or rhetoric (alamk. āra, lit. ornament). It also gives a taster of the Prakrit language (a major component in every Sanskrit drama) in an easily ac- cessible form. Finally it tells the compelling story of Prince Rama in simple elegant Sanskrit: this is the “Ramáyana” faithfully retold. e learned Indian curriculum in late classical times had at its heart a system of grammatical study and linguistic analysis. e core text for this study was the notoriously difficult “Eight Books” (A.s.tādhyāyī) of Pánini, the sine qua non of learning composed in the fourth century , and arguably the most remarkable and indeed foundational text in the history of linguistics. Not only is the “Eight Books” a description of a language unmatched in totality for any language until the nineteenth century, but it is also pre- sented in the most compact form possible through the use xix of an elaborate and sophisticated metalanguage, again un- known anywhere else in linguistics before modern times. -

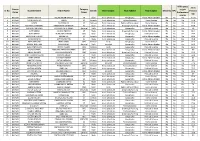

Sr.No. Course Name Student Name Father Name Category Name

Willingness XII th Course Category to join Sr.No. Student Name Father Name Gender Final Subject Final Subject Final Subject Minority BPL Percent Name Name Professional age course 1 BA Part I AAKASH MEENA GULAB SINGH MEENA ST Male Hindi Literature Geography Public Administration No No No 71.14 2 BA Part I AARTI MEROTHA TEJPAL SC Female Hindi Literature Political Science Home Science No Yes No 65.8 3 BA Part I AASHA BAJRANGLAL SC Female Hindi Literature Public Administration Home Science No No No 61.8 4 BA Part I ABHISHEK MEGHWAL RAM KARAN MEGHWAL SC Male Hindi Literature Drawing & Painting Public Administration No No Yes 69.6 5 BA Part I ABHISHEK SHARMA BANVARI LAL SHARMA General Male Hindi Literature Geography Political Science No No Yes 59 6 BA Part I AJAY MEENA JAGDISH MEENA ST Male Hindi Literature Drawing & Painting Public Administration No No No 66.4 7 BA Part I AJAY NAGAR SURAJ MAL NAGAR OBC Male Hindi Literature Geography Political Science No No Yes 74.4 8 BA Part I AKANKSHA KUMARI PANNA LAL ST Female Hindi Literature Geography Public Administration No No No 83.4 9 BA Part I AKASH KUMAR SATYANARAYAN SC Male Hindi Literature Geography Political Science No No Yes 76.8 10 BA Part I AKSA KHANAM IRSAD KHAN OBC Female Urdu Geography Home Science Yes Yes Yes 72.2 11 BA Part I AKSHAT GOUTAM RAMAVATAR General Male Sanskrit Geography Public Administration No No Yes 60.2 12 BA Part I ALISHA MANSURI ZAHID HUSAIN OBC Female Urdu Geography Political Science Yes Yes No 82.6 13 BA Part I ANJALI MEHTA CHANDRA PRAKASH MEHTA OBC Female Hindi Literature -

OLD FLORIDA BOOK SHOP, INC. Rare Books, Antique Maps and Vintage Magazines Since 1978

William Chrisant & Sons' OLD FLORIDA BOOK SHOP, INC. Rare books, antique maps and vintage magazines since 1978. FABA, ABAA & ILAB Facebook | Twitter | Instagram oldfloridabookshop.com Catalogue of Sanskrit & related studies, primarily from the estate of Columbia & U. Pennsylvania Professor Royal W. Weiler. Please direct inquiries to [email protected] We accept major credit cards, checks and wire transfers*. Institutions billed upon request. We ship and insure all items through USPS Priority Mail. Postage varies by weight with a $10 threshold. William Chrisant & Sons' Old Florida Book Shop, Inc. Bank of America domestic wire routing number: 026 009 593 to account: 8981 0117 0656 International (SWIFT): BofAUS3N to account 8981 0117 0656 1. Travels from India to England Comprehending a Visit to the Burman Empire and Journey through Persia, Asia Minor, European Turkey, &c. James Edward Alexander. London: Parbury, Allen, and Co., 1827. 1st Edition. xv, [2], 301 pp. Wide margins; 2 maps; 14 lithographic plates 5 of which are hand-colored. Late nineteenth century rebacking in matching mauve morocco with wide cloth to gutters & gouge to front cover. Marbled edges and endpapers. A handsome copy in a sturdy binding. Bound without half title & errata. 4to (8.75 x 10.8 inches). 3168. $1,650.00 2. L'Inde. Maurice Percheron et M.-R. Percheron Teston. Paris: Fernand Nathan, 1947. 160 pp. Half red morocco over grey marbled paper. Gilt particulars to spine; gilt decorations and pronounced raised bands to spine. Decorative endpapers. Two stamps to rear pastedown, otherwise, a nice clean copy without further markings. 8vo. 3717. $60.00 3. -

Language and Literature

1 Indian Languages and Literature Introduction Thousands of years ago, the people of the Harappan civilisation knew how to write. Unfortunately, their script has not yet been deciphered. Despite this setback, it is safe to state that the literary traditions of India go back to over 3,000 years ago. India is a huge land with a continuous history spanning several millennia. There is a staggering degree of variety and diversity in the languages and dialects spoken by Indians. This diversity is a result of the influx of languages and ideas from all over the continent, mostly through migration from Central, Eastern and Western Asia. There are differences and variations in the languages and dialects as a result of several factors – ethnicity, history, geography and others. There is a broad social integration among all the speakers of a certain language. In the beginning languages and dialects developed in the different regions of the country in relative isolation. In India, languages are often a mark of identity of a person and define regional boundaries. Cultural mixing among various races and communities led to the mixing of languages and dialects to a great extent, although they still maintain regional identity. In free India, the broad geographical distribution pattern of major language groups was used as one of the decisive factors for the formation of states. This gave a new political meaning to the geographical pattern of the linguistic distribution in the country. According to the 1961 census figures, the most comprehensive data on languages collected in India, there were 187 languages spoken by different sections of our society. -

Building a Word Segmenter for Sanskrit Overnight

Building a Word Segmenter for Sanskrit Overnight Vikas Reddy*1, Amrith Krishna*2, Vishnu Dutt Sharma3, Prateek Gupta4, Vineeth M R5, Pawan Goyal2 1Dept. of Mining Engineering, 2Dept. of Computer Science and Engineering, 4Dept. of Mathematics, 5Dept. of Electrical Engineering, 1,2,4,5IIT Kharagpur 3American Express India Pvt Ltd fvikas.challaram, [email protected], [email protected] Abstract There is abundance of digitised texts available in Sanskrit. However, the word segmentation task in such texts are challenging due to the issue of Sandhi. In Sandhi, words in a sentence often fuse together to form a single chunk of text, where the word delimiter vanishes and sounds at the word boundaries undergo transformations, which is also reflected in the written text. Here, we propose an approach that uses a deep sequence to sequence (seq2seq) model that takes only the sandhied string as the input and predicts the unsandhied string. The state of the art models are linguistically involved and have external dependencies for the lexical and morphological analysis of the input. Our model can be trained “overnight” and be used for production. In spite of the knowledge lean approach, our system preforms better than the current state of the art by gaining a percentage increase of 16.79 % than the current state of the art. Keywords: Word Segmentation, Sanskrit, Low-Resource Languages, Sequence to sequence, seq2seq, Deep Learning 1. Introduction proximity between two compatible sounds as per any one Sanskrit had profound influence as the knowledge preserv- of the 281 rules is the sole criteria for sandhi. -

13 Chapter 5.Pdf

-102- CHAPTER V. LIFE AND PERSONALITY OF MAGHA. The classical1 Sk.literature Is enriched with six poems ^ich may be called gems. Three of them -Raghu, Kumara and Megha from the pen ©f Kalidasa, the national poet of India, are called ’Laghu-trayi* while the remaining three- Kirata of Bharavi, Naisa- dha of Sriharsa and Sisu of Magha- are called ’Brihat-trayi*. The ’Sisu*, or as it is better known, the Maghakavya, after the name ©f Its author, is one1,of the master-pieces of Sanskrit literature. It has enjoyed a very high reputation as work of art for over eleven centuries and has been so popular with the scholars as to be ranked by them as the best Kavya. There may be some exaggera- / / tlon in this estimate but it is certain that Sisu has a position of honour in the circle of the learned. It is evident from the Prabandhis, tradition and the 2 colophon at the end of a manuscript of the poem that he belonged to Bhinnamala in Gujarat. It may be noted in this connection that the country ’Gujarat* in the days ©f Magha (6 A.D. t© 7 A.D.) was not co-extensive with modern Gujarat/ What we know as Gujarat today is the country extending roughly from Mt.Abu in the north to Daman in the south, from Dwarka on the Arabian sea in the west to Godhra or Dohad in the east, that is, the country bounded on the north by 1. ' 47V^jr Tfr^T: i ' 2. f jfpt 'mzrjw Int. -

Chapter II * Place of Hevajra Tantraj in Tantric Literature

Chapter II * Place of Hevajra Tantraj in Tantric Literature 4 1. Buddhist Tantric Literature Lama Anagarik Govinda wrote: “the word ‘Tantrd is related to the concept of weaving and its derivatives (thread, web, fabric, etc.), hinting at the interwovenness of things and actions, the interdependence of all that exists, the continuity in the interaction of cause and effect, as well as in spiritual and'traditional development, which like a thread weaves its way through the fabric of history and of individual lives. The scriptures which in Buddhism go under the name of Tantra (Tib.: rgyud) are invariably of a mystic nature, i.e., trying to establish the inner relationship of things: the parallelism of microcosm and macrocosm, mind and universe, ritual and reality, the world of matter and the world of the spirit.”99 Scholars like N.N. Bhattacharyya and also Pranabananda Jash, regard Tantra as a religious system or science (Sastra) dealing with the means (sadhana) of attaining success (siddhi) in secular or religious efforts.100 N.N. Bhattacharyya mentions that “Tantra came to mean the essentials of any religious system and, subsequently, special doctrines and rituals found only in certain forms of various religious systems. This change in the meaning, significance, and character of the word ‘Tantra' is quite striking and is likely to reveal many hitherto unnoticed elements that have characterised the social fabric of India through the ages.”101 It is must be noted that the Tantrika tradition is not the work of a day, it has a long history behind it. Creation, maintenance and dissolution, 99 Lama Anagarika Govinda, Foundations of Tibetan Myticism (Maine: Samuel Weiser, Inc., 1969), p.93. -

Hindi Language and Literature First Degree

HINDI LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE 2017 Admission FIRST DEGREE PROGRAMME IN HINDI Under choice based credit and semester (CBCS) System 2017 Admission onwards 1 Scheme and Syllabi For First Degree Programme in Hindi (Faculty of Oriental Studies) General Scheme Duration : 6 semesters of 18 Weeks/90 working days Total Courses : 36 Total Credits : 120 Total Lecture Hours : 150/Week Evaluation : Continuous Evaluation (CE): 25% Weightage End Semester Evaluation (ESE): 75% (Both the Evaluations by Direct Grading System on a 5 Point scale Summary of Courses in Hindi Course No. of Credits Lecture Type Courses Hours/ Week a. Hindi (For B.A./B.Sc.) Language course : 4 14 18 Additional Language b. Hindi (For B.Com.) Language course : 2 8 8 Additional Language c. First Degree Programme in Hindi Language and Literature Foundation Course 1 3 4 Complementary Course 8 22 24 Core Course 14 52 64 Open Course 2 4 6 Project/Dissertation 1 4 6 A. Outline of Courses B.A./B.Sc. DEGREE PROGRAMMES Course Code Course Type Course Title Credit Lecture Hours/ Week HN 1111.1 Language course (Common Prose And One act 3 4 Course) Addl. Language I ) plays HN 1211.1 Language Course- Common Fiction, Short story, 3 4 (Addl. Language II) Novel HN 1311.1 Language Course- Common Poetry & Grammar 4 5 (Addl. Language III) HN 1411.1 Language Course- Common Drama, Translation 4 5 2 (Addl. Language IV) & Correspondence B.Com. DEGREE PROGRAMME Course Code Course Type Course Title Credit Lecture Hours/ Week HN 1111.2 Language course (Common Prose, Commercial 4 4 Course) Addl. -

The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa, Volume 4

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa, Volume 4 This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa, Volume 4 Books 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 and 18 Translator: Kisari Mohan Ganguli Release Date: March 26, 2005 [EBook #15477] Language: English *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE MAHABHARATA VOL 4 *** Produced by John B. Hare. Please notify any corrections to John B. Hare at www.sacred-texts.com The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa BOOK 13 ANUSASANA PARVA Translated into English Prose from the Original Sanskrit Text by Kisari Mohan Ganguli [1883-1896] Scanned at sacred-texts.com, 2005. Proofed by John Bruno Hare, January 2005. THE MAHABHARATA ANUSASANA PARVA PART I SECTION I (Anusasanika Parva) OM! HAVING BOWED down unto Narayana, and Nara the foremost of male beings, and unto the goddess Saraswati, must the word Jaya be uttered. "'Yudhishthira said, "O grandsire, tranquillity of mind has been said to be subtile and of diverse forms. I have heard all thy discourses, but still tranquillity of mind has not been mine. In this matter, various means of quieting the mind have been related (by thee), O sire, but how can peace of mind be secured from only a knowledge of the different kinds of tranquillity, when I myself have been the instrument of bringing about all this? Beholding thy body covered with arrows and festering with bad sores, I fail to find, O hero, any peace of mind, at the thought of the evils I have wrought. -

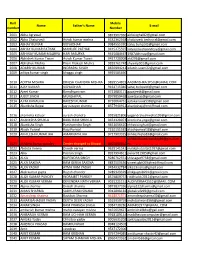

Roll Number Name Father's Name Mobile Number E-Mail 2001 Abha Agrawal 9873907960 [email protected] 2002 Abha Chaturvedi

Roll Mobile Name Father's Name E-mail number Number 2001 Abha Agrawal 9873907960 [email protected] 2002 Abha Chaturvedi Ashok kumar mishra 9532362368 [email protected] 2003 ABHAY KUMAR VIDYADHAR 9984555330 [email protected] 2004 ABHAY KUMAR PATHAK MANI JEE PATHAK 9415275597 [email protected] 2005 ABHINAY KUMAR MAURYA HARI MAURYA 9415684467 [email protected] 2006 Abhishek Kumar Tiwari Ashok Kumar Tiwari 9457728009 [email protected] 2007 Abhishek Mishra Prem Prakash Mishra 9839761748 [email protected] 2008 ADARSH KUMAR INDRAPAL SINGH 8650994242 [email protected] 2009 aditya kumar singh bhaggu singh 9935585690 2010 ADITYA MISHRA DINESH CHANDRA MISHRA 9899554819 [email protected] 2011 AJAY KUMAR VIDYADHAR 9161715046 [email protected] 2012 Ajeet Kumar Ramdhyan ram 9721083171 [email protected] 2013 AJEET SINGH MUNSHI PAL 8979059468 [email protected] 2014 AJITA KANAUJIA RAKESH KUMAR 8726064761 [email protected] 2015 Akanksha Bajpai jay narayan sharma 8377940912 [email protected] 2016 akanksha katiyar suresh chandra 9935821806 [email protected] 2017 AKANKSHA SHUKLA BABU RAM SHUKLA 9454328073 [email protected] 2018 Akanksha Singh Purshpendra Singh 9651656420 [email protected] 2019 Akash Porwal Raju Porwal 7210151583 [email protected] 2020 AKHILESH KUMAR JHA AMARNATH JHA 9717903325 [email protected] [email protected] 2021 akhilesh kumar pandey Center changed to Bhopal 8602093910 m 2022 Akshita Verma Dinesh verma -

What Is Mahāmudrā Traleg Rinpoche

What is Mahāmudrā Traleg Rinpoche The Mahāmudrā tradition encompasses many key Buddhist terms and presents them in a unique light. The Sanskrit word mahāmudrā literally translates as “great seal,’’ or “great symbol,’’ which suggests that all that exists in the conditioned world is stamped with the same seal, the seal of ultimate reality. Ultimate reality is synonymous with the quintessential Buddhist term emptiness (śūnyatā), which describes the insubstantiality of all things—the underlying groundlessness, spaciousness, and indeterminacy that imbues all of our experiences of the subjective and objective world. In the Kagyü tradition of Tibetan Buddhism, the word mahāmudrā is also used to refer to the nature of the mind. The nature of the mind is a pivotal concept in this tradition. The essential quality of the mind is emptiness, but it is described as a luminous emptiness, for the mind has the inherent capacity to know, or to cognize. When spiritual fulfillment is attained, this lumi- nous emptiness is experienced as pervasively and profoundly blissful, and enlightenment is characterized as luminous bliss. The Tibetan term for Mahāmudrā is chag gya chen po. The word chag denotes wisdom; gya implies that this wisdom transcends mental defilement; and chen po verifies that together they express a sense of unity. At a more profound level of interpretation, chag gya suggests that <4> our natural state of being has no origin, because we cannot posit a particular time when it came into being, nor can we say what caused it to conic into existence or what it is dependent upon. Our natural state of being is self-sustaining, self- existing, and not dependent upon anything.