University of Ceylon Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Facets-Of-Modern-Ceylon-History-Through-The-Letters-Of-Jeronis-Pieris.Pdf

FACETS OF MODERN CEYLON HISTORY THROUGH THE LETTERS OF JERONIS PIERIS BY MICHAEL ROBERT Hannadige Jeronis Pieris (1829-1894) was educated at the Colombo Academy and thereafter joined his in-laws, the brothers Jeronis and Susew de Soysa, as a manager of their ventures in the Kandyan highlands. Arrack-renter, trader, plantation owner, philanthro- pist and man of letters, his career pro- vides fascinating sidelights on the social and economic history of British Ceylon. Using Jeronis Pieris's letters as a point of departure and assisted by the stock of knowledge he has gather- ed during his researches into the is- land's history, the author analyses several facets of colonial history: the foundations of social dominance within indigenous society in pre-British times; the processes of elite formation in the nineteenth century; the process of Wes- ternisation and the role of indigenous elites as auxiliaries and supporters of the colonial rulers; the events leading to the Kandyan Marriage Ordinance no. 13 of 1859; entrepreneurship; the question of the conflict for land bet- ween coffee planters and villagers in the Kandyan hill-country; and the question whether the expansion of plantations had disastrous effects on the stock of cattle in the Kandyan dis- tricts. This analysis is threaded by in- formation on the Hannadige- Pieris and Warusahannadige de Soysa families and by attention to the various sources available to the historians of nineteenth century Ceylon. FACETS OF MODERN CEYLON HISTORY THROUGH THE LETTERS OF JERONIS PIERIS MICHAEL ROBERTS HANSA PUBLISHERS LIMITED COLOMBO - 3, SKI LANKA (CEYLON) 4975 FIRST PUBLISHED IN 1975 This book is copyright. -

Reforming Sri Lankan Presidentialism: Provenance, Problems and Prospects Volume 2

Reforming Sri Lankan Presidentialism: Provenance, Problems and Prospects Edited by Asanga Welikala Volume 2 18 Failure of Quasi-Gaullist Presidentialism in Sri Lanka Suri Ratnapala Constitutional Choices Sri Lanka’s Constitution combines a presidential system selectively borrowed from the Gaullist Constitution of France with a system of proportional representation in Parliament. The scheme of proportional representation replaced the ‘first past the post’ elections of the independence constitution and of the first republican constitution of 1972. It is strongly favoured by minority parties and several minor parties that owe their very existence to proportional representation. The elective executive presidency, at least initially, enjoyed substantial minority support as the president is directly elected by a national electorate, making it hard for a candidate to win without minority support. (Sri Lanka’s ethnic minorities constitute about 25 per cent of the population.) However, there is a growing national consensus that the quasi-Gaullist experiment has failed. All major political parties have called for its replacement while in opposition although in government, they are invariably seduced to silence by the fruits of office. Assuming that there is political will and ability to change the system, what alternative model should the nation embrace? Constitutions of nations in the modern era tend fall into four categories. 1.! Various forms of authoritarian government. These include absolute monarchies (emirates and sultanates of the Islamic world), personal dictatorships, oligarchies, theocracies (Iran) and single party rule (remaining real or nominal communist states). 2.! Parliamentary government based on the Westminster system with a largely ceremonial constitutional monarch or president. Most Western European countries, India, Japan, Israel and many former British colonies have this model with local variations. -

PRINCIPAL's PRIZE DAY REPORT 2004 Venerable Chairman

PRINCIPAL’S PRIZE DAY REPORT 2004 Venerable Chairman, Professor Hoole, Dr Mrs Hoole. Distinguished Guests, Old Boys, Parents & Friends St.John’s - nursed, nurtured and nourished by the dedication of an able band of missionary heads, magnificently stands today at the threshold of its 181st year of existence extending its frontiers in the field of education. It is observed that according to records of the college, the very first Prize Giving was ceremoniously held in the year 1891. From then onwards it continues to uphold and maintain this tradition giving it a pride of place in the life of the school. In this respect, we extend to you all a very warm and cordial welcome. Your presence this morning is a source of inspiration and encouragement. Chairman Sir, your association and attachment to the church & the school are almost a decade and a half institutionalizing yourself admirably well in both areas. We are indeed proudly elated by your appointment as our new Manager and look forward to your continued contribution in your office. It is indeed a distinct privilege to have in our midst today, Professor Samuel Ratnajeevan Herbert Hoole & Dr. Mrs. Dushyanthy Hoole as our Chief Guests on this memorable occasion. Professor Sir, you stand here before us as a distinguished old boy and unique in every respect, being the only person in service in this country as a Fellow of the Institute of Electrical & Electronics Engineering with the citation; for contributions to computational methods for design optimization of electrical devices. In addition you hold a higher Doctorate in the field. -

Tides of Violence: Mapping the Sri Lankan Conflict from 1983 to 2009 About the Public Interest Advocacy Centre

Tides of violence: mapping the Sri Lankan conflict from 1983 to 2009 About the Public Interest Advocacy Centre The Public Interest Advocacy Centre (PIAC) is an independent, non-profit legal centre based in Sydney. Established in 1982, PIAC tackles barriers to justice and fairness experienced by people who are vulnerable or facing disadvantage. We ensure basic rights are enjoyed across the community through legal assistance and strategic litigation, public policy development, communication and training. 2nd edition May 2019 Contact: Public Interest Advocacy Centre Level 5, 175 Liverpool St Sydney NSW 2000 Website: www.piac.asn.au Public Interest Advocacy Centre @PIACnews The Public Interest Advocacy Centre office is located on the land of the Gadigal of the Eora Nation. TIDES OF VIOLENCE: MAPPING THE SRI LANKAN CONFLICT FROM 1983 TO 2009 03 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................................... 09 Background to CMAP .............................................................................................................................................09 Report overview .......................................................................................................................................................09 Key violation patterns in each time period ......................................................................................................09 24 July 1983 – 28 July 1987 .................................................................................................................................10 -

Jaffna College Miscellany

JAFFNA COLLEGE MISCELLANY DECEMBER, 1938. % lïtfrrir (Æ jm sim ;« anìr JV jJCajjjiy Jípíu TQtat Jaffna College Miscellany December, 1938- v o l . XLVIII. No. 3. JAFFNA COLLEGE MISCELLANY M a n a g e r : K. Sellaiah. E d i t o r s : S. H. Perinbanayagam. L. S. Kulathungam. The Jaffna College Miscellany is published three times a year, at the close of each term of the College year. The rate of annual subscription is Rs. 2 00 including postage. Advertisement rates are sent on application. Address all business communications and remit all subscriptions to:— The Manager, Jaffna College Miscellany. Vaddukoddai, Ceylon. American Ceylon Mission Press. Tellippalai. CONTENTS P a g e Editorial Notes - 1 My Post-University Course at Jaffna College - 10 A Modern American Theologian 21 ULpWAHjm - So Some Ancient Tamil Poems - 43 Principal’s Notes - 51 Our Results - 56 Parent—Teachers’ Association - 57 The Student Council - 58 The Inter Union -, - 59 “Brotherhood” - 62 Lyceum - 64 Hunt Dormitory Union - 63 The Athenaeum - 68 Scout Notes - 70 Sports Section-Report of the Physical Department— 1938 72 Hastings House - 75 Abraham House - 76 Hitchcock House - 80 Brown House 81 Sports ¡S3 List of Crest Winners 85 Annual Report of the Y. M. C. A. - 87 Jaffna College Alumni Association (News & Notes) 94 Jaffna College Alumni Association (Alumni Day) 97 Treasurer’s Announcement 107 Jaffna College Alumni Association (Statement of Accounts) 108 Jaffna College Alumni Association (List of Members Contribut ions) 109 Principal’s Tea to the Colombo Old Boys - 111 The Silver Jubilee Meeting of the Colombo Old Boys 113 The Silver Jubilee Dinner 117 Old boys News - 123 Notes from the College Diary - 127 The Silver Jubilee Souvenir - 136 Wanted - 140 Silver Jubilee Souvenir of the Old Boys' Association 140 Old Boys’ Register . -

Changing University Student Politics in Sri Lanka: from Norm Oriented to Value Oriented Student Movements*

Social Affairs. Vol.1 No.3, 23-32, Fall 2015 Social Affairs: A Journal for the Social Sciences ISSN 2362-0889 (online) www.socialaffairsjournal.com CHANGING UNIVERSITY STUDENT POLITICS IN SRI LANKA: FROM NORM ORIENTED TO VALUE ORIENTED STUDENT MOVEMENTS* Gamini Samaranayake** Political Scientist ABSTRACT This paper analyzes the causes of student political activism in Sri Lankan universities by paying attention to the history of student politics starting from the 1960s when the first traces of such activism can be traced. Towards this end, it makes use of the analytical framework proposed by David Finlay that explains certain conditions under which students may be galvanized to engage in active politics. Analyzing different socio-political contexts that gave rise to these movements, and the responses of incumbent governments to such situations, it concludes that in order to mitigate the risk of youth getting involved in violent politics, it is necessary to address larger structural issues of inequality. Keywords: Student Politics, Violence, University Education, Sri Lanka INTRODUCTION Student politics is a significant phenomenon sense it could be stated that the universities are in University education in Sri Lanka. The barometers of social and political discontent. involvement of students in politics has a long history and has always reflected the When tracing the history of student politics, social and political changes in the country. it is evident that Sri Lanka did not have Consequently current student councils are a single student movement until 1960. highly politicized bodies and the universities However, with the expansion in the number are strong centers of youth led agitation. -

Chatting Sri Lanka: Powerful Communications in Colonial Times

Chatting Sri Lanka: Powerful Communications in Colonial Times Justin Siefert PhD 2016 Chatting Sri Lanka: Powerful Communications in Colonial Times Justin Siefert A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Manchester Metropolitan University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History, Politics and Philosophy Manchester Metropolitan University 2016 Abstract: The thesis argues that the telephone had a significant impact upon colonial society in Sri Lanka. In the emergence and expansion of a telephone network two phases can be distinguished: in the first phase (1880-1914), the government began to construct telephone networks in Colombo and other major towns, and built trunk lines between them. Simultaneously, planters began to establish and run local telephone networks in the planting districts. In this initial period, Sri Lanka’s emerging telephone network owed its construction, financing and running mostly to the planting community. The telephone was a ‘tool of the Empire’ only in the sense that the government eventually joined forces with the influential planting and commercial communities, including many members of the indigenous elite, who had demanded telephone services for their own purposes. However, during the second phase (1919-1939), as more and more telephone networks emerged in the planting districts, government became more proactive in the construction of an island-wide telephone network, which then reflected colonial hierarchies and power structures. Finally in 1935, Sri Lanka was connected to the Empire’s international telephone network. One of the core challenges for this pioneer work is of methodological nature: a telephone call leaves no written or oral source behind. -

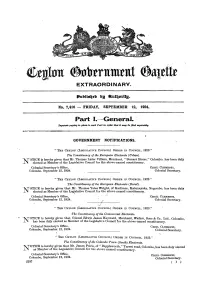

C-Rghni (Mjmimrnl <Sa)Rfte

C-rghni (M jm im rnl <Sa)rfte EXTRAORDINARY. Publt8^Bb b£ Suf^BrttE. No. 7,416 — FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 12, 1924. Part I.—General. Separate paging is given to each Part in order that it may he filed separately. o GOVERNMENT NOTIFICATIONS. “ T h e Ce y l o n (L e g isl a t iv e C o u n c il ) O r d e r in C o u n c il , 1 9 2 3 .” The Constituency of the European Electorate {Urban). OTICE is hereby given that Mr. Thomas Lister Villiers, Merchant, “ Steuart House,” Colombo, has been duly elected as Member of the Legislative Council for the above-named constituency. Colonial Secretary’s Office, Ce c il Cl e m e n t i, Colombo, September 12, 1924. ______________________ Colonial Secretary. “ T h e Ce y l o n (L e g is l a t iv e Co u n c il ) O r d e r in C o u n c il , 1923.” The Constituency of the European Electorate {Rural). X JO T IC E is hereby given that Mr. Thomas Yates Wright, of Kadirane, Katunayaka, Negombo, has been duly JLM elected as Member of the Legislative Council for the above-named constituency. Colonial Secretary’s Office, , • ' Ce c il Cl e m e n t i, Colombo, September 12, 1924. _________ ^ ________ Colonial Secretary. t! T h e Ce y l o n (L e g is l a t iv e C o u n c il ) O r d e r in C o u n c il , 1923.” The Constituency of the Commercial Electorate. -

Jaffna College Miscellany December, 1945

Jaffna College Miscellany December, 1945. •> tr VOL. XLXV NO. J JAFFNA COLLEGE MISCELLANY M a n a g e r : C. -S. Ponnuthurai E d i t o r s : L. S. Kulathungam C. R. Wadsworth The Jaffna College Miscellany is published three times a year, at the close of each term of the College year. The rate of annual subscription is Rs. 2.00 including postage. Advertisement rates are sent on application. Subscribers are kindly requested to notify the Manager any change of address. Address all business communications and remit all subscriptions to:— The Manager, Jaffna College Miscellany, Vaddukoddai, Ceylon. CONTENTS Editorial Notes Left Hand, Right Hand Our Annual Prize-Giving Prize Donors, 1943—1944 Prize Winners The Y. M~ C. A. The Brotherhood The Lyceum The H. S. C. Hostel Union The Athenaeum Tuck-Shop Co-operative Society Junior Geographical Assn. The Wolf Cubs The Poultry Farmers’ Club Brown .House Abraham House The Y. W. C. A. The Scouts Senior Scouts The Girl ^Guides The Brownie Pack Our Results Jaffna College Alumni Association Alumni Notes Principal’s Notes • Further Editorial Notes Notes from a College Diary Stop Press — Malayan Letter r Printed at The. American Ceylon'Mission Press Teflippalai, Ceylon. * Papet hand made from cover to covet1 *57 the American Ceylon Mission Press. &nto U s Q Son is Given * — Given, not lent, And not withdrawn-once sent, This Infant o f mankind, this One, Is still the little welcome Son. New every year, New born and newly dear, He comes with tidings and a song, The ages long, the ages long; Even as the cold Keen winter grows not old, As childhood is so fresh, foreseen, And spring in the familiar green— Sudden as sweet Come the expected feet, All joy is young, and new all art, And H&, too, Whom we have by heart. -

Student Charter

University Student Charter University Student Charter serves as a guide to University Students, Academic, Administrative and Support Staff and Public to Invest and Harvest the Fruits of University Education of the Country. University Grants Commission No. 20 Ward Place Colombo 07 Copyright © University Grants Commission UGC, Sri Lanka All rights reserved. ISBN : 978-955-583-113-0 A publication of the University Grants Commission University Student Charter 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page No. PREFACE 05 PART I Introduction to National University Student Charter 08 Guiding Principles on which National Universities are 11 governed Openness 11 Equity and Diversity 11 Commitment to Uphold Democratic Rights and Social 12 Norms Role of National Universities 13 Centres of Excellence in Teaching and Learning 13 Centres of Excellence in Research and Innovation 15 PART II Academic Atmosphere and Student Support Services 18 Residential Facilities 18 Heath Service 18 Security and Safety 19 Library Service 19 Information Communication Services 19 Career Guidance Services 19 English Language Teaching Programme 20 Sports and Recreational Facilities 20 Multi-cultural Centres 21 Student Support services and Welfare network 21 PART III Governance and Management of National Universities 24 Policy of Withdrawal 25 Freedom of Expression 25 Student Representations 26 Right to form Students’ Associations 26 Personal Conduct 26 Maintenance of Discipline and Law and Order 27 University Student Charter 3 Table of Contents… Page No. PART IV Unethical and Unlawful Activities -

Student Assessment and Examination—Special

Innovative Strategies for Accelerated Human Resource Development in South Asia Student Assessment and Examination Special Focus on Bangladesh, Nepal, and Sri Lanka Assessment of student learning outcomes (ASLO) is one of the key activities in teaching and learning. It serves as the source of information in determining the quality of education at the classroom and national levels. Results from any assessment have an infl uence on decision making, on policy development related to improving individual student achievement, and to ensure the equity and quality of an education system. ASLO provides teachers and school heads with information for making decisions regarding a students’ progress. The information allows teachers and school heads to understand a students’ performance better. This report reviews ASLO in three South Asian countries—Bangladesh, Nepal, and Sri.Lanka—with a focus on public examinations, national assessment, school-based assessment, and classroom assessment practiced in these countries. About the Asian Development Bank ADB’s vision is an Asia and Pacifi c region free of poverty. Its mission is to help its developing member countries reduce poverty and improve the quality of life of their people. Despite the region’s many successes, it remains home to a large share of the world’s poor. ADB is committed to reducing poverty through inclusive economic growth, environmentally sustainable growth, and regional integration. Based in Manila, ADB is owned by members, including from the region. Its main instruments for helping its -

St. John's College Magazine

St. John’s College Magazine Digitized Version of the College Magazine 1905 Converted into Editable Format (MS Word) By Christie. A. Pararajasingam March towards the Bicentennial At the beginning of the year that marked the 195th anniversary of the College, the Principal called upon all the students, staff, parents and well-wishers to join in the march towards the College’sbicentennial. I decided to join the ‘army’ in my own little way. I thought of initiating the process of digitizing and converting all the magazines in the College library into MS Word or other Editable Formats, with the following objectives in mind: To preserve the historic books in the College library for generations to come. To enable the Management and Editors interested to easily search what they are looking for. To enable stakeholders like Old Boys to quickly access the information that they require. To make images easy to extract and reuse. This can’t be done with a PDF, because its images are embedded. To easily edit large areas of text. To make the magazines in the library easily accessible to everyone by uploading them on the internet The oldest magazine in the library, published in 1905 appeared to be the best place to begin work on. The task was much harder than expected, taking more than 50 hours of man hours. Though cumbersome, the walk down memory lane I took, proved to be very informative and enjoyable. I invite you too, to take this walk. Happy reading! Christie A Pararajasingam St. John’s College Magazine 1905 ST. JOHN'S COLLEGE A BRIEF SKETCH OF ITS HISTORY St.