Reforming Sri Lankan Presidentialism: Provenance, Problems and Prospects Volume 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

900 History, Geography, and Auxiliary Disciplines

900 900 History, geography, and auxiliary disciplines Class here social situations and conditions; general political history; military, diplomatic, political, economic, social, welfare aspects of specific wars Class interdisciplinary works on ancient world, on specific continents, countries, localities in 930–990. Class history and geographic treatment of a specific subject with the subject, plus notation 09 from Table 1, e.g., history and geographic treatment of natural sciences 509, of economic situations and conditions 330.9, of purely political situations and conditions 320.9, history of military science 355.009 See also 303.49 for future history (projected events other than travel) See Manual at 900 SUMMARY 900.1–.9 Standard subdivisions of history and geography 901–909 Standard subdivisions of history, collected accounts of events, world history 910 Geography and travel 920 Biography, genealogy, insignia 930 History of ancient world to ca. 499 940 History of Europe 950 History of Asia 960 History of Africa 970 History of North America 980 History of South America 990 History of Australasia, Pacific Ocean islands, Atlantic Ocean islands, Arctic islands, Antarctica, extraterrestrial worlds .1–.9 Standard subdivisions of history and geography 901 Philosophy and theory of history 902 Miscellany of history .2 Illustrations, models, miniatures Do not use for maps, plans, diagrams; class in 911 903 Dictionaries, encyclopedias, concordances of history 901 904 Dewey Decimal Classification 904 904 Collected accounts of events Including events of natural origin; events induced by human activity Class here adventure Class collections limited to a specific period, collections limited to a specific area or region but not limited by continent, country, locality in 909; class travel in 910; class collections limited to a specific continent, country, locality in 930–990. -

Combating the Drug Menace Together

www.thehindu.com 2018-07-22 Combating the drug menace together Even as Colombo steps up efforts to combat drug peddling in the country, authorities have turned to India for help to address what has become a shared concern for the neighbours. Sri Lanka police’s narcotics bureau, amid frequent hauls and arrests, is under visible pressure to tackle the growing drug menace. President Maithripala Sirisena, who controversially spoke of executing drug convicts, has also taken efforts to empower the tri-forces to complement the police’s efforts to address the problem. Further, recognising that drugs are smuggled by air and sea from other countries, Sri Lanka is now considering a larger regional operation, with Indian assistance. “We intend to initiate dialogue with the Indian authorities to get their assistance. We need their help in identifying witnesses needed in our local investigations into smuggling activities,” Law and Order Minister Ranjith Madduma Bandara told local media recently. India’s role, top officials here say, will be “crucial”. The conversation between the two countries has been going on for some time now, after the neighbours signed an agreement on Combating International Terrorism and Illicit Drug Trafficking in 2013, but the problem has grown since. Appreciating the urgency of the matter, top cops from the narcotics control bureaus of India and Sri Lanka, who met in New Delhi in May, decided to enhance cooperation to combat drug crimes. Following up, Colombo has sought New Delhi’s assistance to trace two underworld drug kingpins, believed to be in hiding in India, according to narcotics bureau chief DIG Sajeewa Medawatta. -

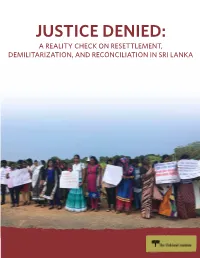

Justice Denied: a Reality Check on Resettlement, Demilitarization, And

JUSTICE DENIED: A REALITY CHECK ON RESETTLEMENT, DEMILITARIZATION, AND RECONCILIATION IN SRI LANKA JUSTICE DENIED: A REALITY CHECK ON RESETTLEMENT, DEMILITARIZATION, AND RECONCILIATION IN SRI LANKA Acknowledgements This report was written by Elizabeth Fraser with Frédéric Mousseau and Anuradha Mittal. The views and conclusions expressed in this publication are those of The Oakland Institute alone and do not reflect opinions of the individuals and organizations that have sponsored and supported the work. Cover photo: Inter-Faith Women’s Group in solidarity protest with Pilavu residents, February 2017 © Tamil Guardian Design: Amymade Graphic Design Publisher: The Oakland Institute is an independent policy think tank bringing fresh ideas and bold action to the most pressing social, economic, and environmental issues. Copyright © 2017 by The Oakland Institute. This text may be used free of charge for the purposes of advocacy, campaigning, education, and research, provided that the source is acknowledged in full. The copyright holder requests that all such uses be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, reuse in other publications, or translation or adaptation, permission must be secured. For more information: The Oakland Institute PO Box 18978 Oakland, CA 94619 USA www.oaklandinstitute.org [email protected] Acronyms CID Criminal Investigation Department CPA Centre for Policy Alternatives CTA Counter Terrorism Act CTF Consultation Task Force on Reconciliation Mechanisms IDP Internally Displaced Person ITJP International Truth and Justice Project LTTE Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam OMP Office on Missing Persons PTA Prevention of Terrorism Act UNCAT United Nations Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment UNHRC United Nations Human Rights Council 3 www.oaklandinstitute.org Executive Summary In January 2015, Sri Lanka elected a new President. -

The Left and the 1972 Constitution: Marxism and State Power

! 8 The Left and the 1972 Constitution: Marxism and State Power g Kumar David ! ! The drafting of the 1972 Republican Constitution was dominated by the larger than life figure of Dr Colvin R. de Silva (hereafter Colvin), renowned lawyer and brilliant orator, neither of which counts for much for the purposes of this chapter. Colvin was also co-leader with Dr N.M. Perera (hereafter NM) of the Lanka Sama Samaja Party (LSSP), and that is the heart of the matter. Although it was known, rather proudly till recently in the party, as ‘Colvin’s Constitution,’ this terminology is emblematic; no, not just a Colvin phenomenon,1 it was a constitution to which the left parties, that is the LSSP and the Communist Party (CP), were inextricably bound. They cannot separate themselves from its conception, gestation and birth; it was theirs as much as it was the child of Mrs Bandaranaike. Neither can the left wholly brush aside the charge that its brainchild facilitated, to a degree, the enactment of a successor, the 1978 J.R. Jayewardene (hereafter JR) Constitution, which iniquity has yet to be exorcised a quarter of a century later. However, even sans this predecessor but with his 5/6th parliamentary majority, JR who had long been committed to a presidential system would in any case have enacted much the same constitution. But overt politicisation, dismantling of checks and balances, and the alienation of the Tamil minority afforded JR a useful platform to launch out from. The relationship of one constitution to the other is not my subject; my task is the affiliation of the LSSP-CP, their avowed Marxism, and the strategic thinking of the leaders to a constitution that can, at least in hindsight, be euphemistically described as controversial. -

Chandrika Kumaratunga (Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga)

Chandrika Kumaratunga (Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga) Sri Lanka, Presidenta de la República; ex primera ministra Duración del mandato: 12 de Noviembre de 1994 - de de Nacimiento: Colombo, Western Province, 29 de Junio de 1945 Partido político: SLNP ResumenLa presidenta de Sri Lanka entre 1994 y 2005 fue el último eslabón de una dinastía de políticos que, como es característico en Asia Indostánica, está familiarizada con el poder tanto como la tragedia. Huérfana del asesinado primer ministro Solomon Bandaranaike, hija de la tres veces primera ministra Sirimavo Bandaranaike ?con la que compartió el Ejecutivo en su primer mandato, protagonizando las dos mujeres un caso único en el mundo- y viuda de un político también asesinado, Chandrika Kumaratunga heredó de aquellos el liderazgo del izquierdista Partido de la Libertad (SLNP) e intentó, infructuosamente, concluir la sangrienta guerra civil con los separatistas tigres tamiles (LTTE), iniciada en 1983, por las vías de una reforma territorial federalizante y la negociación directa. http://www.cidob.org 1 of 10 Biografía 1. Educación política al socaire de su madre gobernante 2. Primera presidencia (1994-1999): plan de reforma territorial para terminar con la guerra civil 3. Segunda presidencia (1999-2005): proceso de negociación con los tigres tamiles y forcejeos con el Gobierno del EJP 1. Educación política al socaire de su madre gobernante Único caso de estadista, mujer u hombre, hija a su vez de estadistas en una república moderna, la suya es la familia más ilustre de la élite dirigente -

ABSTRACTS Engineering Excellence Through Collaborative Research and Innovation ABSTRACTS

General Sir John Kotelawala Defence University Sri Lanka ABSTRACTS Engineering Excellence through Collaborative Research and Innovation ABSTRACTS This book contains the abstracts of papers presented at the 11th International Research Conference of General Sir John Kotelawala Defence University, Ratmalana, Sri Lanka held on 13th - 14th September 2018. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form, without prior permission of General Sir John Kotelawala Defence University, Ratmalana, Sri Lanka Published by General Sir John Kotelawala Defence University Ratmalana 10390 Sri Lanka Tel : +94113370105 E-mail : [email protected] Website : www.kdu.ac.lk/irc2018 ISBN - 978 - 955 - 0301 - 56 - 0 Date of Publication 13th September 2018 Designed and Printed by 2 GENERAL SIR JOHN KOTELAWALA DEFENCE UNIVERSITY 11th INTERNATIONAL RESEARCH CONFERENCE ABSTRACTS CONFERENCE CHAIR Dr Upali Rajapaksha CONFERENCE SECRETARY Ms Bhagya Senaratne AssiSTANT CONFERENCE SECRETARIES Dr Danushi Gunasekara Ms Nirupa Ranasinghe Capt Madhura Rathnayake STEERING COMMITTEE Maj Gen IP Ranasinghe RWP RSP ndu psc - President Brig RGU Rajapakshe RSP psc Professor MHJ Ariyarathne Col JMC Jayaweera psc Senior Professor JR Lucas Capt (S) UG Jayalath Senior Professor ND Warnasuriya Capt JU Gunaseela psc Senior Professor RN Pathirana Lt Col PSS Sanjeewa RSP psc Senior Professor Amal Jayawardane Lt Col WMNKD Bandara RWP RSP Dr (Mrs) WCDK Fernando Lt Col AK Peiris RSP Dr KMG Prasanna Premadasa Capt MP Rathnayake Dr CC Jayasundara -

Discourses of Ethno-Nationalism and Religious Fundamentalism

DISCOURSES OF ETHNO-NATIONALISM AND RELIGIOUS FUNDAMENTALISM SRI LANKAN DISCOURSES OF ETHNO-NATIONALISM AND RELIGIOUS FUNDAMENTALISM By MYRA SIVALOGANATHAN, B.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts McMaster University © Copyright by Myra Sivaloganathan, June 2017 M.A. Thesis – Myra Sivaloganathan; McMaster University – Religious Studies. McMaster University MASTER OF ARTS (2017) Hamilton, Ontario (Religious Studies) TITLE: Sri Lankan Discourses of Ethno-Nationalism and Religious Fundamentalism AUTHOR: Myra Sivaloganathan, B.A. (McGill University) SUPERVISOR: Dr. Mark Rowe NUMBER OF PAGES: v, 91 ii M.A. Thesis – Myra Sivaloganathan; McMaster University – Religious Studies. Abstract In this thesis, I argue that discourses of victimhood, victory, and xenophobia underpin both Sinhalese and Tamil nationalist and religious fundamentalist movements. Ethnic discourse has allowed citizens to affirm collective ideals in the face of disparate experiences, reclaim power and autonomy in contexts of fundamental instability, but has also deepened ethnic divides in the post-war era. In the first chapter, I argue that mutually exclusive narratives of victimhood lie at the root of ethnic solitudes, and provide barriers to mechanisms of transitional justice and memorialization. The second chapter includes an analysis of the politicization of mythic figures and events from the Rāmāyaṇa and Mahāvaṃsa in nationalist discourses of victory, supremacy, and legacy. Finally, in the third chapter, I explore the Liberation Tiger of Tamil Eelam’s (LTTE) rhetoric and symbolism, and contend that a xenophobic discourse of terrorism has been imposed and transferred from Tamil to Muslim minorities. Ultimately, these discourses prevent Sri Lankans from embracing a multi-ethnic and multi- religious nationality, and hinder efforts at transitional justice. -

Minutes of Parliament Present

(Ninth Parliament - First Session) No. 62.] MINUTES OF PARLIAMENT Thursday, March 25, 2021 at 10.00 a.m. PRESENT : Hon. Mahinda Yapa Abeywardana, Speaker Hon. Angajan Ramanathan, Deputy Chairperson of Committees Hon. Mahinda Amaraweera, Minister of Environment Hon. Dullas Alahapperuma, Minister of Power Hon. Mahindananda Aluthgamage, Minister of Agriculture Hon. Udaya Gammanpila, Minister of Energy Hon. Dinesh Gunawardena, Minister of Foreign and Leader of the House of Parliament Hon. (Dr.) Bandula Gunawardana, Minister of Trade Hon. Janaka Bandara Thennakoon, Minister of Public Services, Provincial Councils & Local Government Hon. Nimal Siripala de Silva, Minister of Labour Hon. Vasudeva Nanayakkara, Minister of Water Supply Hon. (Dr.) Ramesh Pathirana, Minister of Plantation Hon. Johnston Fernando, Minister of Highways and Chief Government Whip Hon. Prasanna Ranatunga, Minister of Tourism Hon. C. B. Rathnayake, Minister of Wildlife & Forest Conservation Hon. Chamal Rajapaksa, Minister of Irrigation and State Minister of National Security & Disaster Management and State Minister of Home Affairs Hon. Gamini Lokuge, Minister of Transport Hon. Wimal Weerawansa, Minister of Industries Hon. (Dr.) Sarath Weerasekera, Minister of Public Security Hon. M .U. M. Ali Sabry, Minister of Justice Hon. (Dr.) (Mrs.) Seetha Arambepola, State Minister of Skills Development, Vocational Education, Research and Innovation Hon. Lasantha Alagiyawanna, State Minister of Co-operative Services, Marketing Development and Consumer Protection ( 2 ) M. No. 62 Hon. Ajith Nivard Cabraal, State Minister of Money & Capital Market and State Enterprise Reforms Hon. (Dr.) Nalaka Godahewa, State Minister of Urban Development, Coast Conservation, Waste Disposal and Community Cleanliness Hon. D. V. Chanaka, State Minister of Aviation and Export Zones Development Hon. Sisira Jayakody, State Minister of Indigenous Medicine Promotion, Rural and Ayurvedic Hospitals Development and Community Health Hon. -

Strategic Plan 2017-2020 Election Commission of Sri Lanka 2017-2020

STRATEGIC PLAN STRATEGIC PLAN 2017-2020 ELECTION COMMISSION OF SRI LANKA 2017-2020 Department of Government Printing STRATEGIC PLAN 2017-2020 Election Commission of Sri Lanka Participatory Strategic Plan (PSP) of the Election Commission of Sri Lanka for 2017-2020 “Everyone has the right to take part in the government of his country, directly or through freely chosen representatives... The will of the people shall be the basis of the authority of government; this will, shall be expressed in periodic ndenineeetinieniendeend shall be held by secret vote or by equivalent free voting procedures.” Article 21, Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 1948 Participatory Strategic Plan (PSP) Election Commission of Sri Lanka 2017-2020 I Foreword By the Chairman and the Members of the Commission Mahinda Deshapriya N. J. Abeysekere, PC Prof. S. Ratnajeevan H. Hoole Chairman Member Member The Soulbury Commission was appointed in 1944 by the British Government in response to strong inteeneeinetefittetetenteineentte population in the governance of the Island, to make recommendations for constitutional reform. The Soulbury Commission recommended, interalia, legislation to provide for the registration of voters and for the conduct of Parliamentary elections, and the Ceylon (Parliamentary Election) Order of the Council, 1946 was enacted on 26th September 1946. The Local Authorities Elections Ordinance was introduced in 1946 to provide for the conduct of elections to Local bodies. The Department of Parliamentary Elections functioned under a Commissioner to register voters and to conduct Parliamentary elections and the Department of Local Government Elections functioned under a Commissioner to conduct Local Government elections. The “Department of Elections” was established on 01st of October 1955 amalgamating the Department of Parliamentary Elections and the Department of Local Government Elections. -

Sri Lanka's Potemkin Peace: Democracy Under Fire

Sri Lanka’s Potemkin Peace: Democracy Under Fire Asia Report N°253 | 13 November 2013 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i Recommendations..................................................................................................................... iii I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Northern Province Elections and the Future of Devolution ............................................ 2 A. Implementing the Thirteenth Amendment? ............................................................. 3 B. Northern Militarisation and Pre-Election Violations ................................................ 4 C. The Challenges of Victory .......................................................................................... 6 1. Internal TNA discontent ...................................................................................... 6 2. Sinhalese fears and charges of separatism ........................................................... 8 3. The TNA’s Tamil nationalist critics ...................................................................... 9 D. The Legal and Constitutional Battleground .............................................................. 12 E. A Short- -

Facets-Of-Modern-Ceylon-History-Through-The-Letters-Of-Jeronis-Pieris.Pdf

FACETS OF MODERN CEYLON HISTORY THROUGH THE LETTERS OF JERONIS PIERIS BY MICHAEL ROBERT Hannadige Jeronis Pieris (1829-1894) was educated at the Colombo Academy and thereafter joined his in-laws, the brothers Jeronis and Susew de Soysa, as a manager of their ventures in the Kandyan highlands. Arrack-renter, trader, plantation owner, philanthro- pist and man of letters, his career pro- vides fascinating sidelights on the social and economic history of British Ceylon. Using Jeronis Pieris's letters as a point of departure and assisted by the stock of knowledge he has gather- ed during his researches into the is- land's history, the author analyses several facets of colonial history: the foundations of social dominance within indigenous society in pre-British times; the processes of elite formation in the nineteenth century; the process of Wes- ternisation and the role of indigenous elites as auxiliaries and supporters of the colonial rulers; the events leading to the Kandyan Marriage Ordinance no. 13 of 1859; entrepreneurship; the question of the conflict for land bet- ween coffee planters and villagers in the Kandyan hill-country; and the question whether the expansion of plantations had disastrous effects on the stock of cattle in the Kandyan dis- tricts. This analysis is threaded by in- formation on the Hannadige- Pieris and Warusahannadige de Soysa families and by attention to the various sources available to the historians of nineteenth century Ceylon. FACETS OF MODERN CEYLON HISTORY THROUGH THE LETTERS OF JERONIS PIERIS MICHAEL ROBERTS HANSA PUBLISHERS LIMITED COLOMBO - 3, SKI LANKA (CEYLON) 4975 FIRST PUBLISHED IN 1975 This book is copyright. -

Annual Report 1964-65

1964-65 Content Jan 01, 1964 CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE I. India's Policy of Non-alignment 1-6 II. United Nations and International Conferences 7-19 III. Disarmament 20-23 IV. India's Neighbours 24-42 V. States in Special Treaty Relations with India 43-46 VI. South East Asia 47-51 VII. East Asia 52-55 VIII. West Asia and North Africa 66-57 IX. Africa south of the Sahara 58-60 X. Eastern and Western Europe 61-73 XI. The Americas 74-78 XII. External Publicity 79-83 XIII. Technical and Economic Co-operation 84-87 XIV. Consular and Passport Services 88-95 XV. Organisation and Administration 96-104 (i) (ii) PAGE Appendix I. Declaration of Conference of Non-aligned Countries 105-122 Appendix II. International Organisations of which India is a member 123-126 Appendix III. Commonwealth Prime Ministers' Final Com- munique, July 1994 127-134 Appendix IV. Indo-Ceylon Agreement 135-136 Appendix V. Distinguished visitors from abroad 137-141 Appendix VI. Visits of Indian Dignitaries to foreign countries 142-143 Appendix VII. Soviet-Indian Joint Communique 144-147 Appendix VIII. Technical Co-operation 148-150 Appendix IX. Economic Collaboration 151-152 Appendix X. Foreign Diplomatic Missions in India 153-154 Appendix XI. Foreign Consular Offices in India 155-157 Appendix XII. Indian Missions Abroad 158-164 INDIA Jan 01, 1964 INDIA'S POLICY OF NON-ALIGNMENT CHAPTER I INDIA'S POLICY OF NON-ALIGNMENT India, ever since her independence, has consistently followed in her foreign relations a policy of non-alignment with the opposing power blocs.