Justice Delayed, Justice Denied? the Search for Accountability for Alleged Wartime Atrocities Committed in Sri Lanka

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sri Lanka 2020 Human Rights Report

SRI LANKA 2020 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Sri Lanka is a constitutional, multiparty democratic republic with a freely elected government. Presidential elections were held in 2019, and Gotabaya Rajapaksa won the presidency. He appointed former president Mahinda Rajapaksa, his brother, as prime minister. On August 5, Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapaksa led the Sri Lankan People’s Freedom Alliance and small allied parties to secure a two- thirds supermajority, winning 150 of 225 seats in parliamentary elections. COVID-19 travel restrictions prevented international observers and limited domestic election observation. Domestic observers described the election as peaceful, technically well managed, and safe considering the COVID-19 pandemic but noted that unregulated campaign spending, abuse of state resources, and media bias affected the level playing field. The Sri Lanka Police are responsible for maintaining internal security and are under the Ministry of Public Security, formed on November 20. The military, under the Ministry of Defense, may be called upon to handle specifically delineated domestic security responsibilities, but generally without arrest authority. The nearly 11,000-member paramilitary Special Task Force, a police entity that reports to the inspector general of police, coordinates internal security operations with the military. Civilian officials maintained control over the security forces. Members of the security forces committed some abuses. The Sri Lanka parliament passed the 20th Amendment to the constitution on October 22. Opposition political leaders and civil society groups widely criticized the amendment for its broad expansion of executive authority that activists said would undermine the independence of the judiciary and independent state institutions, such as the Human Rights Commission and the Elections Commission, by granting the president sole authority to make appointments to these bodies with parliament afforded only a consultative role. -

Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia List of Commanders of the LTTE

4/29/2016 List of commanders of the LTTE Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia List of commanders of the LTTE From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The following is a list of commanders of theLiberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), also known as the Tamil Tigers, a separatist militant Tamil nationalist organisation, which operated in northern and eastern Sri Lanka from late 1970s to May 2009, until it was defeated by the Sri Lankan Military.[1][2] Date & Place Date & Place Nom de Guerre Real Name Position(s) Notes of Birth of Death Thambi (used only by Velupillai 26 November 1954 19 May Leader of the LTTE Prabhakaran was the supreme closest associates) and Prabhakaran † Velvettithurai 2009(aged 54)[3][4][5] leader of LTTE, which waged a Anna (elder brother) Vellamullivaikkal 25year violent secessionist campaign in Sri Lanka. His death in Nanthikadal lagoon,Vellamullivaikkal,Mullaitivu, brought an immediate end to the Sri Lankan Civil War. Pottu Amman alias Shanmugalingam 1962 18 May 2009 Leader of Tiger Pottu Amman was the secondin Papa Oscar alias Sivashankar † Nayanmarkaddu[6] (aged 47) Organization Security command of LTTE. His death was Sobhigemoorthyalias Kailan Vellamullivaikkal Intelligence Service initially disputed because the dead (TOSIS) and Black body was not found. But in Tigers October 2010,TADA court judge K. Dakshinamurthy dropped charges against Amman, on the Assassination of Rajiv Gandhi, accepting the CBI's report on his demise.[7][8] Selvarasa Shanmugam 6 April 1955 Leader of LTTE since As the chief arms procurer since Pathmanathan (POW) Kumaran Kankesanthurai the death of the origin of the organisation, alias Kumaran Tharmalingam Prabhakaran. -

General Jagath Jayasuriya

MISSÕES GENERAL DIPLOMÁTICAS JAGATH JAYASURIYA SURINAME Jagath Jayasuriya COLÔMBIA recebe suas credenciais no Suriname e se Sri Lanka, maio de 2009: Jagath Jayasuriya usa encontra com o uma boina negra. A sua direita está Shavendra Ministro da Defesa Silva (comandante da divisão 58) e a sua direita, em junho de 20169. Jagath Dias (comandante da divisão 57). PERU JAGATH JAYASURIYA Jagath Jayasuriya foi nomeado embaixador em agosto de 201512 e chegou em novembro, BRASIL juntamente com sua esposa, Manjulika13. JAGATH DIAS SHAVENDRA SILVA “Estou disposto a investigar alegações, alegações Jagath Jayasuriya específicas, não quero varrer apresentou suas credenciais na nada para debaixo do tapete”. Colômbia em fevereiro de 201710. JAGATH JAYASURIYA (2011)1 O embaixador Jagath Jayasuriya compareceu à CHILE cerimônia de posse Como alto oficial do Alegações de que Jagath do presidente em exército, Jagath Jayasuriya Jayasuriya, em sua função Lima em 28 de julho 11 nomeia uma equipe de de Chefe do Estado- de 2016 . seis membros para que Maior da Defesa, tentou CARREIRA MILITAR investiguem: (a) a morte mobilizar o exército para de civis durante a última que interferisse nas fase da guerra civil, eleições presidenciais (b) a informação contida de janeiro de 2015, nas gravações do canal proporcionando segurança. de televisão britânico Foi interceptado um Channel 4 sobre a execução memorando, supostamente de prisioneiros tâmeis assinado por Jagath Comandante Comandante 7 DE AGOSTO2 A 15 DE JULHO 15 DE JULHO amarrados e nus por Jayasuriya em dezembro de forças de divisão 52 DE 2009: Chefe do quartel- Nomeado comandante segurança de general das forças de 19 do exército do soldados3.Esta investigação Nomeado Chefe 2014, que abre caminho Jaffna segurança de Vanni (também Sri Lanka. -

Combating the Drug Menace Together

www.thehindu.com 2018-07-22 Combating the drug menace together Even as Colombo steps up efforts to combat drug peddling in the country, authorities have turned to India for help to address what has become a shared concern for the neighbours. Sri Lanka police’s narcotics bureau, amid frequent hauls and arrests, is under visible pressure to tackle the growing drug menace. President Maithripala Sirisena, who controversially spoke of executing drug convicts, has also taken efforts to empower the tri-forces to complement the police’s efforts to address the problem. Further, recognising that drugs are smuggled by air and sea from other countries, Sri Lanka is now considering a larger regional operation, with Indian assistance. “We intend to initiate dialogue with the Indian authorities to get their assistance. We need their help in identifying witnesses needed in our local investigations into smuggling activities,” Law and Order Minister Ranjith Madduma Bandara told local media recently. India’s role, top officials here say, will be “crucial”. The conversation between the two countries has been going on for some time now, after the neighbours signed an agreement on Combating International Terrorism and Illicit Drug Trafficking in 2013, but the problem has grown since. Appreciating the urgency of the matter, top cops from the narcotics control bureaus of India and Sri Lanka, who met in New Delhi in May, decided to enhance cooperation to combat drug crimes. Following up, Colombo has sought New Delhi’s assistance to trace two underworld drug kingpins, believed to be in hiding in India, according to narcotics bureau chief DIG Sajeewa Medawatta. -

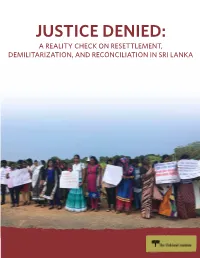

Justice Denied: a Reality Check on Resettlement, Demilitarization, And

JUSTICE DENIED: A REALITY CHECK ON RESETTLEMENT, DEMILITARIZATION, AND RECONCILIATION IN SRI LANKA JUSTICE DENIED: A REALITY CHECK ON RESETTLEMENT, DEMILITARIZATION, AND RECONCILIATION IN SRI LANKA Acknowledgements This report was written by Elizabeth Fraser with Frédéric Mousseau and Anuradha Mittal. The views and conclusions expressed in this publication are those of The Oakland Institute alone and do not reflect opinions of the individuals and organizations that have sponsored and supported the work. Cover photo: Inter-Faith Women’s Group in solidarity protest with Pilavu residents, February 2017 © Tamil Guardian Design: Amymade Graphic Design Publisher: The Oakland Institute is an independent policy think tank bringing fresh ideas and bold action to the most pressing social, economic, and environmental issues. Copyright © 2017 by The Oakland Institute. This text may be used free of charge for the purposes of advocacy, campaigning, education, and research, provided that the source is acknowledged in full. The copyright holder requests that all such uses be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, reuse in other publications, or translation or adaptation, permission must be secured. For more information: The Oakland Institute PO Box 18978 Oakland, CA 94619 USA www.oaklandinstitute.org [email protected] Acronyms CID Criminal Investigation Department CPA Centre for Policy Alternatives CTA Counter Terrorism Act CTF Consultation Task Force on Reconciliation Mechanisms IDP Internally Displaced Person ITJP International Truth and Justice Project LTTE Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam OMP Office on Missing Persons PTA Prevention of Terrorism Act UNCAT United Nations Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment UNHRC United Nations Human Rights Council 3 www.oaklandinstitute.org Executive Summary In January 2015, Sri Lanka elected a new President. -

Ranil Wickremesinghe Sworn in As Prime Minister

September 2015 NEWS SRI LANKA Embassy of Sri Lanka, Washington DC RANIL WICKREMESINGHE VISIT TO SRI LANKA BY SWORN IN AS U.S. ASSISTANT SECRETARIES OF STATE PRIME MINISTER February, this year, we agreed to rebuild our multifaceted bilateral relationship. Several new areas of cooperation were identified during the very successful visit of Secretary Kerry to Colombo in May this year. Our discussions today focused on follow-up on those understandings and on working towards even closer and tangible links. We discussed steps U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for taken by the Government of President South and Central Asian Affairs Nisha Maithripala Sirisena to promote recon- Biswal and U.S. Assistant Secretary of ciliation and to strengthen the rule of State for Democracy, Human Rights law as part of our Government’s overall Following the victory of the United National Front for and Labour Tom Malinowski under- objective of ensuring good governance, Good Governance at the general election on August took a visit to Sri Lanka in August. respect for human rights and strength- 17th, the leader of the United National Party Ranil During the visit they called on Presi- ening our economy. Wickremesinghe was sworn in as the Prime Minister of dent Maithirpala Sirisena, Prime Min- Sri Lanka on August 21. ister Ranil Wickremesinghe and also In keeping with the specific pledge in After Mr. Wickremesinghe took oaths as the new met with Minister of Foreign Affairs President Maithripala Sirisena’s mani- Prime Minister, a Memorandum of Understanding Mangala Samaraweera as well as other festo of January 2015, and now that (MoU) was signed between the Sri Lanka Freedom government leaders. -

Hansard (213-16)

213 වන කාණ්ඩය - 16 වන කලාපය 2012 ෙදසැම්බර් 08 වන ෙසනසුරාදා ெதாகுதி 213 - இல. 16 2012 சம்பர் 08, சனிக்கிழைம Volume 213 - No. 16 Saturday, 08th December, 2012 පාලෙනත වාද (හැනසා) பாராமன்ற விவாதங்கள் (ஹன்சாட்) PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) ල වාතාව அதிகார அறிக்ைக OFFICIAL REPORT (අෙශෝධිත පිටපත /பிைழ தித்தப்படாத /Uncorrected) අන්තර්ගත පධාන කරුණු නිෙව්දන : විෙශෂේ ෙවෙළඳ භාණ්ඩ බදු පනත : ෙපොදු රාජ මණ්ඩලීය පාර්ලිෙම්න්තු සංගමය, අන්තර් නියමය පාර්ලිෙම්න්තු සංගමය සහ “සාක්” පාර්ලිෙම්න්තු සංගමෙය් ඒකාබද්ධ වාර්ෂික මහා සභා රැස්වීම නිෂපාදන් බදු (විෙශෂේ විධිවිධාන) පනත : ශී ලංකා පජාතාන්තික සමාජවාදී ජනරජෙය් නිෙයෝගය ෙශෂේ ඨාධිකරණෙය්් අග විනිශචයකාර් ධුරෙයන් ගරු (ආචාර්ය) ශිරානි ඒ. බණ්ඩාරනායක මහත්මිය ඉවත් කිරීම සුරාබදු ආඥාපනත : සඳහා අතිගරු ජනාධිපතිවරයා ෙවත පාර්ලිෙම්න්තුෙව් නියමය ෙයෝජනා සම්මතයක් ඉදිරිපත් කිරීම පිණිස ආණ්ඩුකම වවසථාෙව්් 107(2) වවසථාව් පකාර ෙයෝජනාව පිළිබඳ විෙශෂේ කාරක සභාෙව් වාර්තාව ෙර්ගු ආඥාපනත : ෙයෝජනාව පශනවලට් වාචික පිළිතුරු වරාය හා ගුවන් ෙතොටුෙපොළ සංවර්ධන බදු පනත : ශී ලංකාෙව් පථම චන්දිකාව ගුවන්ගත කිරීම: නිෙයෝගය විදුලි සංෙද්ශ හා ෙතොරතුරු තාක්ෂණ අමාතතුමාෙග් පකාශය ශී ලංකා අපනයන සංවර්ධන පනත : විසර්ජන පනත් ෙකටුම්පත, 2013 - [විසිතුන්වන ෙවන් කළ නිෙයෝගය දිනය]: [ශීර්ෂ 102, 237-252, 280, 296, 323, 324 (මුදල් හා කමසම්පාදන);] - කාරක සභාෙව්දී සලකා බලන ලදී. -

CHAP 9 Sri Lanka

79o 00' 79o 30' 80o 00' 80o 30' 81o 00' 81o 30' 82o 00' Kankesanturai Point Pedro A I Karaitivu I. Jana D Peninsula N Kayts Jana SRI LANKA I Palk Strait National capital Ja na Elephant Pass Punkudutivu I. Lag Provincial capital oon Devipattinam Delft I. Town, village Palk Bay Kilinochchi Provincial boundary - Puthukkudiyiruppu Nanthi Kadal Main road Rameswaram Iranaitivu Is. Mullaittivu Secondary road Pamban I. Ferry Vellankulam Dhanushkodi Talaimannar Manjulam Nayaru Lagoon Railroad A da m' Airport s Bridge NORTHERN Nedunkeni 9o 00' Kokkilai Lagoon Mannar I. Mannar Puliyankulam Pulmoddai Madhu Road Bay of Bengal Gulf of Mannar Silavatturai Vavuniya Nilaveli Pankulam Kebitigollewa Trincomalee Horuwupotana r Bay Medawachchiya diya A d o o o 8 30' ru 8 30' v K i A Karaitivu I. ru Hamillewa n a Mutur Y Pomparippu Anuradhapura Kantalai n o NORTH CENTRAL Kalpitiya o g Maragahewa a Kathiraveli L Kal m a Oy a a l a t t Puttalam Kekirawa Habarane u 8o 00' P Galgamuwa 8o 00' NORTH Polonnaruwa Dambula Valachchenai Anamaduwa a y O Mundal Maho a Chenkaladi Lake r u WESTERN d Batticaloa Naula a M uru ed D Ganewatta a EASTERN g n Madura Oya a G Reservoir Chilaw i l Maha Oya o Kurunegala e o 7 30' w 7 30' Matale a Paddiruppu h Kuliyapitiya a CENTRAL M Kehelula Kalmunai Pannala Kandy Mahiyangana Uhana Randenigale ya Amparai a O a Mah Reservoir y Negombo Kegalla O Gal Tirrukkovil Negombo Victoria Falls Reservoir Bibile Senanayake Lagoon Gampaha Samudra Ja-Ela o a Nuwara Badulla o 7 00' ng 7 00' Kelan a Avissawella Eliya Colombo i G Sri Jayewardenepura -

Air Annual Issue, Vol. 1, 2017

Grasp the pattern, read the trend Asia in Review (AiR) Brought to you by CPG AiR Annual Issue, Vol. 1, 2017 Table of Contents I. Law and Politics in Asia ............................................................................................................................................................................3 1. Bangladesh ...................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 2. Cambodia ......................................................................................................................................................................................... 9 3. China .............................................................................................................................................................................................. 19 4. India ............................................................................................................................................................................................... 45 5. Indonesia ........................................................................................................................................................................................ 61 6. Japan .............................................................................................................................................................................................. 76 7. Laos ............................................................................................................................................................................................... -

October 19, 2020 the Honorable Michael R. Pompeo Secretary Of

October 19, 2020 The Honorable Michael R. Pompeo Secretary of State U.S. Department of State 2201 C Street, NW Washington, D.C. 20520 Re: Request to address deteriorating human rights situation during Oct. 27 visit with Sri Lanka’s President and Prime Minister Dear Secretary Pompeo: I am writing on behalf of Amnesty International and our 10 million members, supporters and activists worldwide. Founded in 1961, Amnesty International is a global human rights movement that was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1977 for contributing to “securing the ground for freedom, for justice, and thereby also for peace in the world.” Amnesty’s researchers and campaigners work out of the International Secretariat, which over the last decade, has established regional offices around the world, bringing our staff closer to the ground. The South Asia Regional Office was established in 2017 in Colombo, Sri Lanka to lead Amnesty's human rights work on Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, the Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka. Amnesty's South Asia Regional Office has carefully documented the deterioration of the human rights situation in Sri Lanka under the current government. Impunity persists for new and past human rights violations. We ask that during your upcoming visit to Sri Lanka, you call on President Gotabaya Rajapaksa and Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapaksa to reverse some of their recent actions which undermine human rights and take steps to address impunity. Under the current government, the space for dissent and criticism is rapidly shrinking, as demonstrated by a series of cases, including the harassment of New York Times journalist Dharisha Bastians, the arbitrary detention of blogger Ramzy Razeek and lawyer Hejaaz Hizbullah, and the ongoing criminal investigation against writer Shakthika Sathkumara. -

Sri Lanka – Colonel Karuna – Abductions – Joseph Pararajasingham

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: LKA31328 Country: Sri Lanka Date: 16 February 2007 Keywords: Sri Lanka – Colonel Karuna – Abductions – Joseph Pararajasingham This response was prepared by the Country Research Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. Questions 1. Please provide any information you have about the physical appearance, age, background, etc, of LTTE Commander Karuna. 2. Please provide current information about Karuna. 3. Please provide information about the murder of MP Joseph Pararajasingham. RESPONSE (Note: There is a range of transliteral spelling from non-English languages into English. In this Country Research Response the spelling is as per the primary source document). 1. Please provide any information you have regarding the physical appearance, age, background, etc, of LTTE Commander Karuna. “Colonel Karuna” is the nom de guerre of Vinayagamoorthi Muralitharan. Karuna was born in Kiran in the Batticaloa district of Sri Lanka. A 2004 BBC News profile of Karuna describes him as being 40 years old whilst Wikipedia1 information gives his year of birth as 1966. A photograph of Karuna is printed in the attached BBC News profile (Gopalakrishnan, Ramesh 2004, ‘Profile: Colonel Karuna’, BBC News, 5 March http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/south_asia/3537025.stm – Accessed 7 February 2007 – Attachment 1; ‘Karuna: Rebels’ rebel’ 2004, The Sunday Times (Sri Lanka), 7 March http://www.sundaytimes.lk/040307/ – Accessed 7 February 2007 – Attachment 2; ‘Colonel Karuna’ 2007, Wikipedia, 27 January http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Colonel_Karuna – Accessed 7 February 2007 – Attachment 3). -

In the Court of Appeal of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka

IN THE COURT OF APPEAL OF THE DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA In the matter of an application for a mandate in the nature of Writ of Certiorari and Prohibition in terms of Article 140 of the Constitution CA (Writ) Application No: 148 /2012 J. M. Lakshman Jayasekara Director General, National Physical Planning Department 5th Floor, Sethsiti paya, Battaramulla. PETITIONER 1. S.M.Gotabaya Jayarathne, Secretary, Ministry of Construction, Engineering Services, Housing & Common Amenities, 5th Floor C,Sethsiripaya, Battaramulla. 1st RESPONDENT 1.A P.H.L. Wimalasiri Perera Secretary, Ministry of Construction, Engineering Services, Housing & Common Amenities, 5th Floor C,Sethsiripaya, Battaramulla Present Secretary ADDED 1A RESPONDENT 2. Vidyajothi Dr. Dayasiri Fernando, Chairman, 3. Palitha Kumarasinghe P.C, Member, 4. Mrs. Sirimavo A. Wijayaratne, Member, 5. Ananda Seneviratne, Member 6. N.H. Pathirana, Member, 7. S. Thillanadarajah, Member, 8. M.B.W. Ariyawansa, Member, 9. M.A.Mohomed Nahiya, Member, 10. P.M.L.C. Seneviratne Secretary, All of Public Services Commission, 177, Nawala Road, Colombo 5. 11. Attorney General Attorney General's department, Colombo 12. 12. Hon. Prime Minister D. M. Jayaratne Ministry of Buddha Sasana & Religious Affairs 13. Hon. Ratnasiri Wickramanayake Ministry of Good Governance & Infrastructure Facilities 14. Hon. D. E. W. Gunasekera Ministry of Human Resources 15. Hon. Athauda Seneviratne Ministry of Rural Affairs 16. Hon. P. Dayaratne Ministry of Food Security 17. Hon. A. H. M. Fowzie Ministry of Urban Affairs 18. Hon. S. B. Navinne Ministry of Consumer Welfare 19. Hon. Piyasena Gamage Ministry of National Resources 20. Hon. (Prof) Tissa Vitharana Ministry of Scientific Affairs 21.